WE ARE ONLY SEEN WHEN WE DIE: NOTES ON THE WAR AND ART IN UKRAINE By Alisa Lozhkina

“HOW ARE YOU?,” collective art project at Yermilov Centre, Kharkiv, February 24 - March 6, 2022

I am part of a collective body attacked by another collective body. The body of my homeland is aching and writhing in pain; I cannot remain indifferent. But is there any room for “me” in this situation? My consciousness is flooded with multitudes. “We Ukrainians must...,” “those Russians have no right...,” “the West should...,” “we cultural figures address....” The word “freedom” in my language comes from an ancient Indo-European root meaning one’s own, denoting a separate position from others. By attacking the country where I was born and had lived until recently, where my mother and grandmother remained, Russia has deprived me of my freedom. I can no longer live my life. I read the news and check social media all day long. My friends, acquaintances, millions of displaced people, and residents of besieged cities are howling in despair in my head. Somewhere in the other hemisphere of my brain I hear the murmur of Russian propaganda. I can’t stop resenting the scale of the lies some of these people choose to believe.

There is much that is personal in this text. In peacetime, this is not typical of me. I tend to hide behind other people’s stories. My profession, as an art historian and curator, taught me that. It is important for me to say the word “I” now, because all these events are cruelly taking it away from me.

Colleagues in Ukraine unanimously declare the need for a total boycott of everything connected with Russia – including its culture. I advocate a more nuanced approach; I want to be tolerant and argue for building bridges with Russian dissidents. But then I see pictures from Mariupol, which the Russians are razing to the ground, or the now-ruined suburbs of Kiev, where I spent my childhood, and a sharp dagger of hatred plunges into my heart. I don’t hate anyone in particular, I hate “them” – the still-abstract multitude that attacked my home. This is what is so terrible about aggression: it puts people in a desperate situation, making them hate and dehumanize in return.

Hotel Ukraine in Chernihiv, destroyed by a Russian airstrike, March 2022

We are only seen when we die. Having worked with contemporary Ukrainian art all my life, I know very well how indifferent the international art world is to our problems, and how little is known about us outside of the very chambered social bubbles in a few countries. Ukraine is not exotic enough to be admired for its “otherness,” nor is it completely “Western,” to be accepted as an equal in Europe. The art of Ukraine is perceived hierarchically – like an iceberg. Its tiny top consists of a few figures visible on the international scene, but under the water, invisible to the observer, there is a huge, lively, and interesting social and artistic universe.

For a Ukrainian artist to be heard outside the country, she must be adequate and predictable, obediently producing works on the themes that international curators and viewers expect from Ukraine – corruption of officials, life in a post-Soviet landscape, brutality of power, and now, of course, war. An artist from Ukraine cannot afford the luxury of addressing abstract topics in her work. She is considered interesting only if she plays the role of a herald of the collective body. This system of a non-obvious but very clear institutional mandate reminds me a lot of the one we had in our countries during the Soviet period. Only now we are dealing with capitalist realism instead of socialist realism.

Being a curator or art critic in Ukraine is not an enviable fate either. We have practically no international career; we are driven into a very narrow niche and always have to prove something to those around us: that we exist, that we do interesting projects, that our country has a very rich artistic tradition. In 2010, Sergey Anufriev, an artist from Odessa, made a work based on folk tales. It consisted of an empty pedestal for an artwork with the caption Invisible Hat. For many years it seemed to me that all our art was covered by this Invisible Hat, that it is this Hat that makes us invisible to those around us. I even thought that if I were to create a museum of contemporary art in Ukraine, I would probably exhibit just this piece.

Today, the world has put a sharp focus on us. This, of course, is good, although I would have preferred obscurity in exchange for peace. Producing many texts and projects on the war in Ukraine, I cannot shake the feeling that I am working in the genre of disaster porn.

And yet, it is especially important to talk about Ukrainian art today. As a critic and curator, I have long been interested in the art of protests and revolutions. Crisis is a time when you recall that art has magical roots. It has an immense power, and it is not for nothing that dictators are always afraid of it. In Ukraine, we know it firsthand from the experience of recent revolutions. In a moment of turbulence, art transcends its white cube by moving into the street and experiences a brief but unforgettable moment of acute social demand.

Our country certainly has many political difficulties. But it has no shortage of talented people. When Russia attacked, artists all over Ukraine started reflecting on the war almost immediately. During the 2013–14 revolution, there was a surge of artistic activity in Ukraine as well. Photography became the main medium at that time. Many artists normally working in painting, sculpture, or installation art took cameras and went to Maidan, documenting the faces of protesters, huge ice barricades, and Molotov cocktails flying into police columns. This time it’s completely different. The photography is there, but it is reduced to a dry and scary document. For most artists, drawing has become the main way of talking about the war. A quick sketch, which does not require much time or expensive materials, has its objective advantages, of course. However, it seems to me that the choice of drawing has a deeper logic. In the years since our last revolution, we have also stopped trusting photography. It has turned from evidence into an element of manipulation and post-truth. We all know that some media lie by using the verisimilitude of the photograph to push emotions.

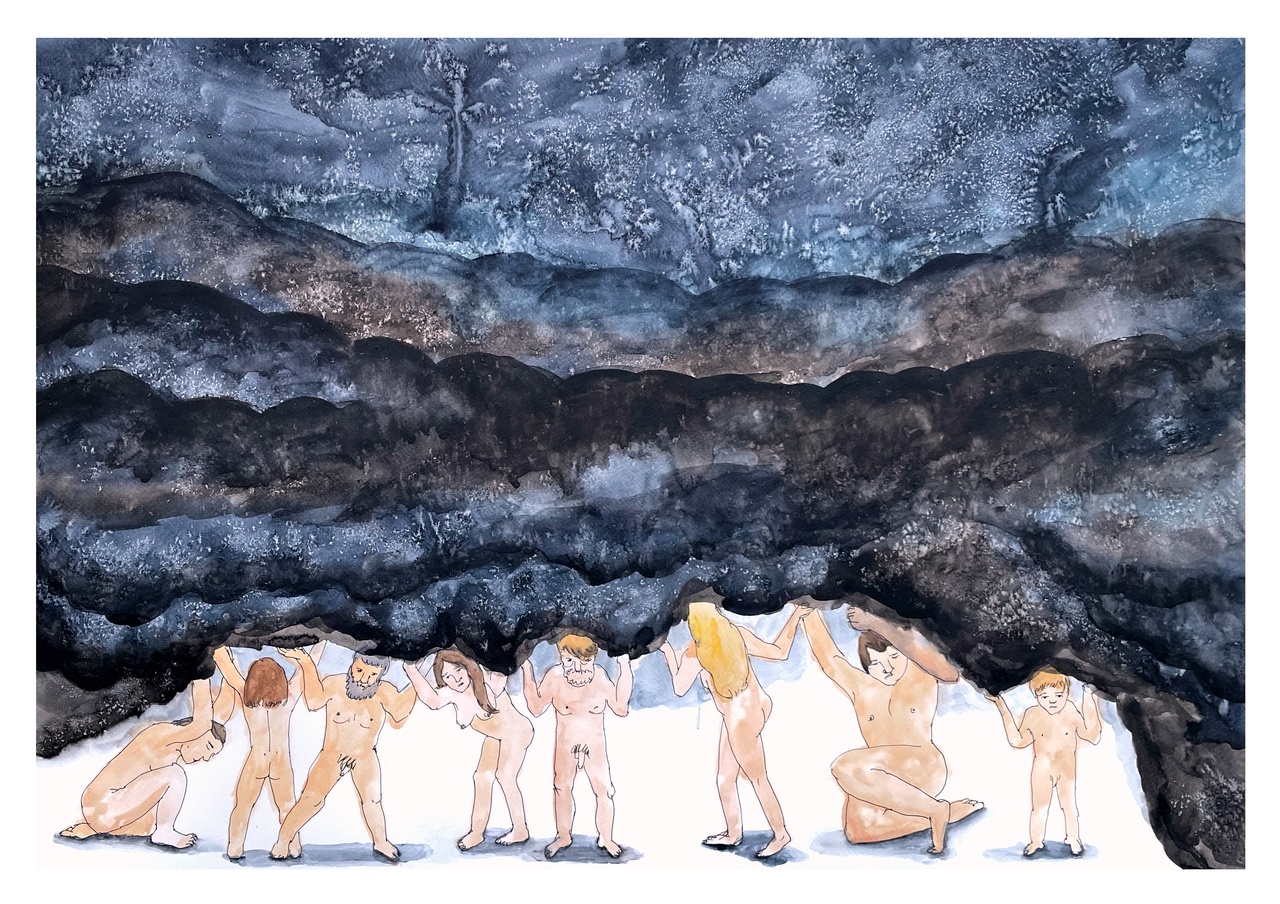

Kinder Album, “Ukrainian Titans Hold up the Sky,” March 2022

In this situation, drawing has an added advantage. Behind it, one hears the clear and recognizable voice of the author, the very broken self that is having such a hard time during the war. Such a story is believable – it tells something deeply intimate and personally experienced. One of the strongest projects of the first month of the war are the drawings of the female artist from Lviv who hides behind the pseudonym Kinder Album. Day by day the artist documents her mental states and social experiences. Women stopping tanks with their bare hands; a group of people holding the heavens on their shoulders; Death; figures transporting children killed during the war in boats on the river Styx. These simple and vivid works are both uplifting and heartbreaking. Lviv, where Kinder Album lives, is relatively safe in the very west of Ukraine. Hundreds of thousands of refugees from all over the country come there. Gradually, cultural life resumes in the city. One of the most dynamic institutions of contemporary art, the Lviv Municipal Art Center, reopened with an exhibition of war drawings by Kinder Album.

Drawing dominates, but there still is a place for other media. An important artistic testimony from the war-torn Kharkiv is a documentary project How Are You? From February 24th, day one of the invasion, through March 6, dozens of artists and their families were hiding from air strikes in a basement of the most well-known contemporary art gallery in Kharkiv, the Yermilov Centre. Among them was Pavlo Makov – he will be representing Ukraine this year at the Venice Biennale. Banal everyday photos and videos document the life of the artists in the gallery, which for two weeks was turned into a bomb shelter. People watch films, cover windows with protective shields, eat, sleep, and have long conversations. It looks like some awkward indoor picnic, but endless explosions can be heard. The gallery is located in the heart of the city, in the basement of a constructivist building at Kharkiv’s Karazin University. By an ironic twist of fate, these are the areas of Kharkiv that have been most affected by the bombing. The curators of How Are You? emphasize that these photos are the documentation of a performance. Referring to Ilya Kabakov’s immersive artworks, they call the gallery turned into a bomb shelter a “total installation.” Dissociation is one of the main mechanisms that help one cope with trauma during war. “It’s not me, not with me, it’s all just a total installation...”

Alisa Lozhkina is an independent curator and art critic from Kyiv, Ukraine currently based in the San Francisco Bay Area. She is the author of Permanent Revolution: Art in Ukraine, 20th to early-21st Century published in Ukrainian and English by ArtHuss (Kyiv, Ukraine) and in French by Nouvelles Editions Place (Paris, France).

Image credits: 1. Courtesy of Elisa Mamardashvili; 2. Photo: Lesya Kharchenko; 3. Courtesy of Kinder Album