Art Without a Shadow Sven Lütticken on Walid Raad at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

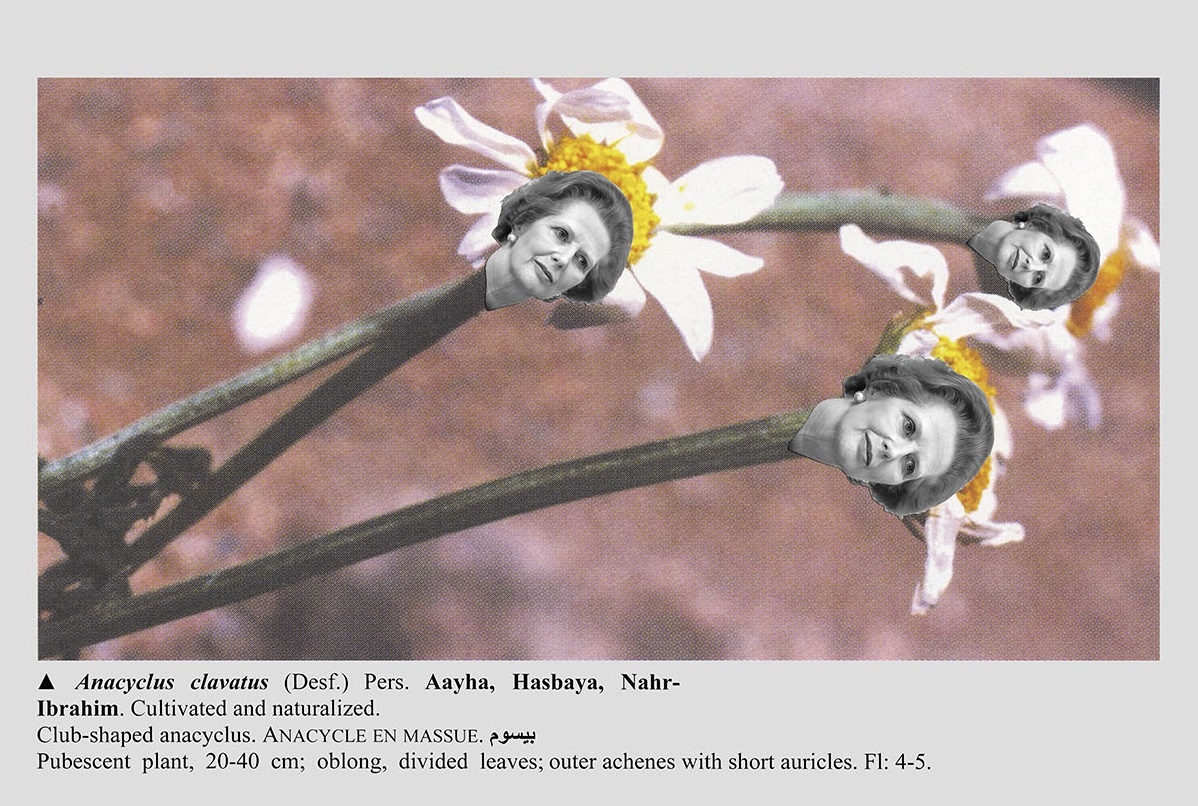

Walid Raad, “Better be watching the clouds_plate0094 (Thatcher),” 2000

Walid Raad’s exhibition “Let’s Be Honest, the Weather Helped” is a carefully composed mini-retrospective of which three rooms also double as set for his performance piece Les Louvres and/or Kicking the Dead (2017–ongoing), which Raad has performed a number of times during the run of the exhibition. Comprising a number of rooms on the top floor of the Stedelijk Museum’s original building, “Let’s Be Honest” forsook chronology for resonance and rhyme, with the central rooms combining works from different projects: The Atlas Group (1989–2004), Sweet Talk Commissions Beirut (1987–ongoing), and Scratching on Things I Could Disavow (2007–ongoing). With Raad, one finds oneself on slippery terrain even when making such factual art-historical statements, as some of the dates are fictional or narrativized rather than factual. Raad practices antedating on a scale that would leave Kandinsky or Malevich speechless, and most Atlas Group works come with two dates, with the former referring to the alleged donation of the materials and the latter to the realization of the work. Furthermore, artworks can migrate from the context of one project to another. Sweet Talk Commissions Beirut focuses on the changing urban landscape of Beirut and the physical manifestations of real estate speculation in the city; these days, it is Raad who is credited with the photos and footage that constitutes this series, but the early piece Sweet Talk: The Hilwé Commissions (1992–2004) has been presented as a commission by the Atlas Group – Raad’s fictitious collective of documentarians and archivists, which by now serves more as the name of a project than as a collective author name – to the dancer and photographer Lamia Hilwé. [1]

While this work is not part of the Stedelijk show, it featured the 2019 piece Sweet Talk: Commissions (Storefronts: 1987–2005): a series of Atget/Evans-type photos of modest Beirut storefronts that is credited to Raad with an accompanying backstory: “In 1984, as a budding photographer, I was thrilled to be hired by a cousin in the local militia, to photograph various storefronts. […] Years later, I found out that the stores’ owners had refused to pay the ‘security fees’ imposed on them by my cousin’s militia, leading to the owners being beaten or exiled, and their businesses confiscated.” Very similar photos were published by Raad in 1999 as belonging to “The Beirut Al-Hadath Archive,” as the result of a large-scale collective photographic mapping of Beirut by numerous commissioned photographers. [2] The Al-Hadath Archive, in turn, appears to have been a trial run of the Atlas Group, which Raad likewise started in 1999 (its alleged inception in 1989 notwithstanding).

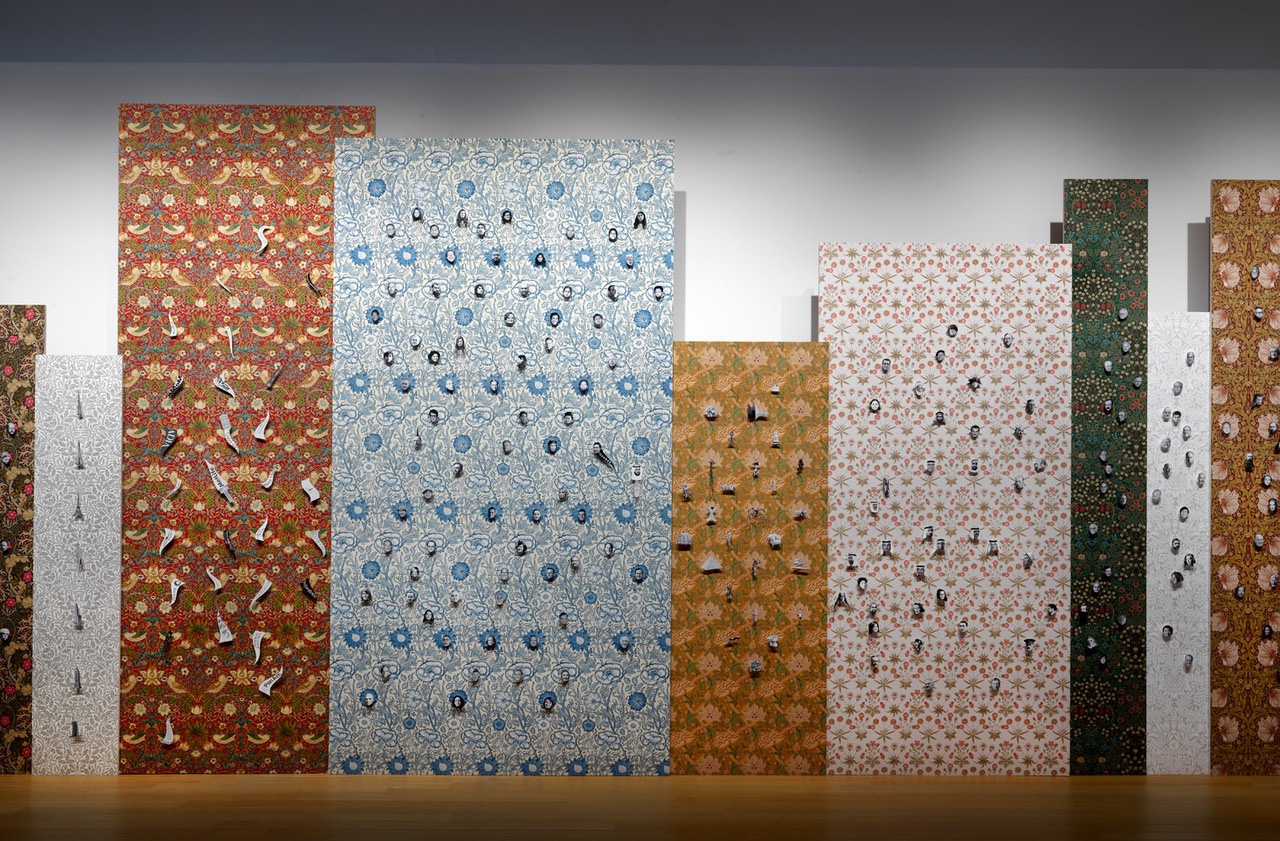

“Walid Raad: Let’s be honest, the weather helped,” Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 2019, installation view

The Atlas Group engaged in what one could call forensic fiction, questioning the supposed ontological superiority of photography as an indexical medium, with much of the work effectively being an imaginative application of Walter Benjamin’s point about the importance of captions in photography: the titles and accompanying texts frame, and in many ways “make,” the images. Raad’s Atlas Group works also explore the tension between figuration and abstraction: in the series Let’s Be Honest, the Weather Helped (1996–2001), images of buildings damaged in the Lebanese Civil War are overlaid with colored dots that are supposedly a color-coded system revealing the nationalities of the makers of the ammunition that did the damage; on the other hand, the three blue monochromes from Secrets in the Open Sea (1994–2004) supposedly contain group portraits that are invisible to the naked eye; these photos are included as small inserts in the margin, and they allegedly depict people drowned in the Mediterranean. At some moments, the blue monochromes resonate with the shimmering Mediterranean in one of the Atlas Group videos (I Only Wish That I Could Weep, 2001).

The screening room combines Atlas Group work and more recent videos from the context of Scratching on Things I Could Disavow, an ongoing series (including the Les Louvres performance) that focuses on art in the Arab world and the booming art market in the Gulf region, which propels the franchising of Western museums such as the Louvre and the Guggenheim in Abu Dhabi. One hilarious short video shows textile restorers fussing over a Persian carpet from the Louvre that has allegedly “lost its voice,” while another shows crated artworks being driven through the Louvre’s underground tunnels in order to be shipped to the Abu Dhabi franchise, accompanied by a narrative about the artworks losing their shadows in transit. This motif plays a central role in Preface to the Third Edition: Acknowledgements (2016): three freestanding monochrome panels that face the Secrets in the Open Sea triptych. The panels’ irregular contours are inspired by the “extensions” of Persian miniatures, with trees protruding past the frame of the image; supposedly, the specific shapes and colors of these panels serve to reveal that the objects mounted have “traded faces,” or swapped surfaces. They have also, as per the video, lost their shadows; to help them regain their real shadows, Raad painted fake shadows on the panels as a form of entrapment.

These panels are one stop during Raad’s Les Louvres performance, which starts in the video room before leading past the Preface to the Third Edition panels to a third space containing two installations. During the first part, Raad delivers a virtuoso PowerPoint lecture that introduces various motifs that will continue to be interwoven throughout the talk: the art collection formerly belonging to All Quiet on the Western Front author Erich Maria Remarque supposedly having ended up in Ypres, a town dominated by the memory of WWI, where an American expat named Jack – a former forensic examiner who certified 30,000 deaths, having the power to decide not over life and death, but who is officially dead and who remains undead, in limbo – is trying to get away from his ghosts; a narrative about Cooper Union, where Raad teaches, being forced to introduce tuition fees due to financial and real estate speculation involving a colorful cast of corporate characters, including MetLife, which lent Cooper Union $175 million for a new building, and Tishman Speyer, which owns New York’s MetLife Building. The carpet restoration video and the Louvre tunnel video are included as well, with the latter setting up the group’s move to the adjacent space and Preface to the Third Edition.

In the last room, Raad continues in front of panels with floral William Morris wallpaper on which cut-out head and corporate logos have been pinned; essentially, the wallpaper functions as a dizzying kind of quasi-flow chart. In the video installation that accompanied his 2012 performance Walkthrough (Translator’s Introduction: Pension Arts in Dubai), Raad likewise crafted imaginative diagrams of power. Here, the artists talks the audience through some of the connections, informing us that his mother worked as a “wallpaper tester,” and zapping from Fritz Haber’s invention of the gas deployed in Ypres during WWI to the “skyscraper index” that links the construction of the “world’s tallest buildings” to financial crashes. Cooper Union owns the ground underneath the Chrysler building (finished just in time for the 1929 crash). Tishman Speyer – which of course has also done business with Jared Kushner, whose face is also on the wallpaper – not only owns the MetLife building but also used to own the Chrysler building before selling it to Abu Dhabi; this means that Abu Dhabi now pays Cooper Union rent for the ground. As Raad puts it in the performance: “My salary comes from the United Arab Emirates. And I cannot tell you how much I had not known this.” Somewhere along the line, Raad mentions that the Louvre Abu Dhabi bought the Yves Saint-Laurent collection, which boasts a number of examples of vintage William Morris wallpaper. In the past, Sheikh Khalifa supposedly also bought the art collection of Erich Maria Remarque and Paulette Goddard (whose ex, Charlie Chaplin, was an obsession of the Sheikh’s). However, these paintings died, or became undead, in transit; like vampires, they sat in crates/coffins that smelled of putrescence and to which they always returned no matter how hard the Sheikh’s art advisor, Hanan, tried to ditch them. It was only when Hanan painted copies on the outside of the crates, repelling them like a mirror repels a vampire, that it was possible to lay them to something resembling rest – in Ypres, where Jack takes care of them. Les Louvres and/or Kicking the Dead ends in front of a wall that, behind a half-opened black curtain, shows the crates with the copies of the undead paintings on the outside.

As in Walkthrough, his earlier Scratching on Things I Could Disavow performance, with its narrative about Moti Shniberg and the Artist Pension Trust, Raad includes a lot of factual material. Versions of the previous script were published with disclaimers reading variously “This work is, in part, a work of fiction,” and “This text is (here and there) a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.” [3] Clearly, some of the key elements in both pieces are anything but; at times they come close to being (or seeming like) a fairly classic form of institutional critique, with Raad making visible financial interests and networks of power. There are fairly obvious links between these works from the Scratching on Things I Could Disavow series and Raad’s activities in the context of Gulf Labor, which has protested against the working conditions of construction workers on Saadiyat Island, the site of both the Louvre Abu Dhabi and the on-again/off-again Guggenheim. Raad, however, insists on keeping the two separate: art operates in a different register from activism. For Hans Haacke, there is a continuum between his participation in Gulf Labor and his art; differences between them are differences in degree within a single form of aesthetic practice. For Raad, they are differences in kind between different forms of practice.

“Walid Raad: Let’s be honest, the weather helped,” Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 2019, installation view

One can question this somewhat rigid binarism and argue that the disclaimers undermine his performances. Particularly in conversations about his work, there is the sense that Raad ultimately glosses over the contradictions in his work by positing neatly separated realms. However, his insistence on the aesthetic and poetic specificity of art also provides a cover for different forms of truth-telling. Whereas Forensic Architecture occasionally find themselves discredited by politicians for being a mere “artist group” whose reconstructions should not be taken seriously, Raad – as an artist – makes a different kind of claim. [4] “Some artworks die,” Raad says, quoting some apocryphal Sheikh – and this, he insists, is to be understood not metaphorically but literally. This trope of artworks dying, or becoming undead vampires, losing their shadows, reflects his ongoing exchange with Jalal Toufic. [5] In the process, Raad reimagines institutional critique as a gothic tale. In 1813, as Napoleon’s Empire – which was also a massive art-looting operation, centered around the Musée Napoléon in the Louvre – was collapsing, the French-German aristocrat wrote Peter Schlemihl, about a man who sells his shadow. With Raad, as tradition withdraws in the face of a surpassing disaster, it is artworks that lose their faces and their shadows.

If Raad is interested in keeping art and activism apart, he actively brings theatricality into the exhibition. Some of the works in the show were stage props to varying degrees, especially the large sculptures from the series I Feel a Great Desire to Meet the Masses Once Again, which are combinations of crates forming the outlines of hybrid figures, underpinned by another Raad story about public artworks that were hastily disassembled and crates at the outbreak of the Lebanese Civil War, with nobody bothering to note down instructions for reassembly. Dramatically lit, the sculptures cast large shadows that feel like more simulations, more fakes. Meanwhile, Scratching on Things I Could Disavow: Act XII_Scene XVII (2019) is an installation with a red frieze on the wall that serve as a background or framing device for various reliefs and – accompanied by more narratives about artworks losing their shadows, exhibition spaces becoming unreal, and the absence of reflections on the museum floor – again a vampiric motif. A profile delineating an absent space suggests a phantasmagorical Kulissenwelt, a theatre of flimsy backdrops and spectral actors. Quite a few of Raad’s more recent works seem like sets waiting for actors, even when they don’t literally function as such. Performance takes center stage and is present even during the lengthy intermissions.

During Les Louvres and/or Kicking the Dead, Raad uses himself as a medium, as a kind of messianic seismograph – or a living camera, indexing an unfolding historical cataclysm. It just so happens that the shadow is a classic instance of the Peircean index, a proto-photo. Now, in the age of lost shadows, it is no longer the photographic apparatus but the human subject registering the historical tremors directly. Art’s task, then, becomes a matter of “checking” the initial subjective-indexical revelation – “checking” being the term Raad uses in conversation. While he encourages viewers to do their homework after the performance, clearly this checking is not to be confused with mundane fact-checking: rather, it is the intimation of catastrophe that is “verified” both by gathering verifiable facts and by spinning operative fictions that help make sense of such facts, which narrativize them. The role of fiction has thus changed since The Atlas Group: the work is no longer about casting doubt on indexical truth, but about checking a different kind of index – the tremors of the loss of the index, of the shadow, as felt by the artist-subject – by means of narrative and performance. Wearing a baseball cap that supposedly serves as an antidote to his panic attacks, the artist’s persona stages the script as an intersubjective experiment, the enactment of a truth that is a performative gamble. In contrast to post-truth performances by today’s demagogues, Raad sows doubt throughout – though perhaps the pirouettes he dances around the audience are never more dazzling than when he discusses the transformation of Abu Dhabi’s construction workers into “bio batteries” via a patch that turns their sweat into electricity, and the involvement of a “piss and shit institute” from Oregon. Faced with (and part of) Raad’s artefacts, the viewers become co-performers whose role may also involve checking and indeed challenging the artist and his carefully calibrated script.

“Walid Raad: Let’s Be Honest, the Weather Helped,” Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, May 18–October 13, 2019.

Notes

| [1] | See pp. 108–15 of The Atlas Group (1989–2004): A Project by Walid Raad, Berlin/Cologne: Hamburger Bahnhof/Walther König, 2006. |

| [2] | Walid Ra’ad, “The Beirut Al-Hadath Archive,” in: Rethinking Marxism, vol. 11, no. 1, 1999, pp. 15–29; see also Christoph Chwatal, “Labyrinth and Rhizome: On the Work of Walid Raad,” https://stedelijkstudies.com/journal/labyrinth-and-rhizome-on-the-work-of-walid-raad/#_ednref5. |

| [3] | The first disclaimer is from the script as published as a booklet in the cassette Walid Raad, Walkthrough (London: Black Dog, 2014); the second from the e-flux journal version published in no. 48 (October 2013) and no. 49 (November 2013). |

| [4] | See Forensic Architecture, “Response to the report presented by the CDU parliamentary group in Hessen on 25 August 2017,” https://docplayer.net/89579517-Forensic-architecture-centre-for-research-architecture-department-of-visual-cultures.html. |

| [5] | See in particular (Vampires): An Uneasy Essay on the Undead in Film (Barrytown NY: Station Hill Press, 1993) and The Withdrawal of Tradition Past a Surpassing Disaster (Forthcoming Books, 2009); the latter is dedicated to Raad. |