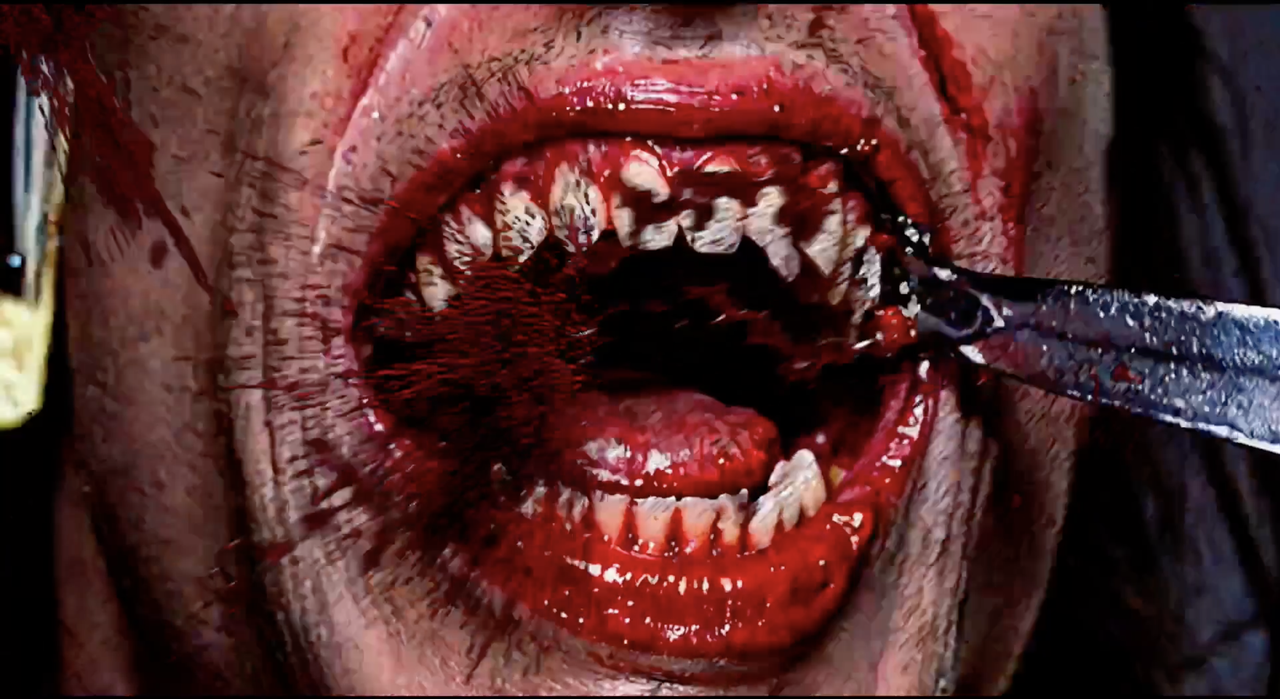

DRACULA’S FASCINATIONS: VAMPIRES IN THE AGE OF AI Daniel Schwartz on Radu Jude’s “Dracula”

Radu Jude, “Dracula,” 2025

The term fascination comes by way of the Latin fascinum, an amulet that takes the form of a winged penis worn to ward off the evil eye; to fascinate (fascinare) is to invoke the power of this phallus to bewitch or protect. Judged by the preponderance of dildos, dick jokes, and penises in Radu Jude’s recent films (think Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn, 2021), one might suppose the brilliant Romanian director is trying to cast a protective spell. His latest film, Dracula, is no exception. Indeed, it takes this tendency to the extreme – characters are just as likely to be sodomized by flying AI-generated cocks as to be bitten by a vampire or have a stake driven through their hearts. All these, to be fair, amount to more or less the same thing. The Dracula legend abounds in phallic imagery that belies its main obsession: castration anxiety. This obsession dates back to the stakes that Vlad the Impaler, the original Dracula (if Dracula can be said to have an original), used to drive through the anal cavities of his enemies. It only makes sense that an AI film seeking to reclaim Dracula for Transylvania – and that is concerned with how much Romania has been fucked (by the EU, the transition to neoliberal capitalism, etc.) – is literally exploding with dicks.

Jude’s Dracula is a monstrous mash-up of shortish vampire movies that combine video-game aesthetics, AI glitch, and DIY filmmaking to interrogate the reign of contemporary post-democratic capitalism – the perfect combination of American free markets (read: monopolies) and East European despotism – the worst of both worlds. On paper, this sounds amazing (at least to me). On screen, it leaves a lot to be desired. The whole film runs for an excruciating three hours, during which the same gags are repeated ad nauseam. That’s kind of the point: to stage the stomach-churning spectacle of AI devouring its own cultural representations and precursors.

Stitching these short films together is a meta-narrative about a Transylvanian director (Adonis Tanța) struggling to write a Dracula screenplay. With the help of his trusty AI assistant, he creates 14 scenarios using Chat GPT-style prompts – “GPT, make an essay film about Dracula featuring lots of dicks,” and so on. Having been generated, these are then screened to demonstrate AI’s (in)abilities. We see Dracula à la Bram Stoker, F. W. Murnau, and Francis Ford Coppola. We see him as a merciless Romanian capitalist, a TikTok influencer, a nostalgic Romanian king, an old, impoverished prostitute, and much else besides. He even takes a tour in a lorry on a Socialist-era collective farm, this time in the guise of a woman (Ilinca Manolache), who vaguely hints at the tradition of female vampires (vagina dentata) in the works of E. T. A. Hoffmann (Aurelia in “Vampirismus,” 1821), Edgar Allan Poe (“Berenice,” 1835), and Charles Baudelaire (“Les métamorphoses du vampire,” 1857). All these vampiric appearances and AI-literalized metaphors make the film’s argument perfectly clear: AI is a vampire – culturally, emotionally, economically, environmentally, perhaps even literally (imagine a world where you pay for your GPT subscription with blood that is used to keep Sam Altman alive forever). But does that mean the film has to be one too?

Radu Jude, “Dracula,” 2025

Dracula is painfully aware and defensive of its argument in a way that nullifies its charm as a low-budget film. Inspired by the work of other makers of vampire films, such as Roger Corman and Jess Franco, not to mention the maximalist Coppola, it nevertheless departs from their traditions by offering its own postmortem. Such preemptive self-analysis comes by way of a warning issued by the film’s fictional director to its would-be critic. Don’t bother regurgitating ideas from Franco Moretti’s famous essay on vampires, “The Dialectic of Fear,” he warns. And don’t bother citing Marx’s somewhat anti-Semitic dictum: “Capital is dead labour, which, vampire-like, lives only by sucking living labour, and lives the more, the more labour it sucks.” [1] (Earlier in the same text, Marx writes: “The capitalist knows that all commodities, however tattered they may look, or however badly they may smell, are in faith and in truth money, are by nature circumcised Jews …”) [2] Dracula as the personification of capital is an idea so old it seems hardly worth mentioning. The same goes for anti-Semitic tropes that Jude lampoons throughout his work. But I can’t help myself. I can only defend the filmmaker’s and the critic’s right to regurgitate ideas, especially Marxist ones.

Moretti juxtaposes Frankenstein and Dracula along the lines of proletarian and capitalist. Frankenstein – or, rather, Frankenstein’s monster, for the monster himself only bears the name of his inventor – is proletarian. “Like the proletariat, he is a collective and artificial creature. He is not found in nature, but built,” [3] invented, stitched together from different pieces. By contrast, Dracula, though nominally an aristocrat, is in fact a monopoly capitalist – or, in Marxist terms, capital personified. He is looking to make a real-estate deal. He is “a saver, an ascetic, an upholder of the Protestant ethic,” who never wastes a drop of blood. “His body admittedly exists, but it is ‘incorporeal’ – ‘sensibly supersensible’ as Marx wrote of the commodity.” [4] He moves across borders and through walls with the freedom of money.

Jude would like to ally his film with Frankenstein. Indeed, his fictional director makes this point explicitly, saying that he would have preferred naming the film after Mary Shelley’s monster. (Is it a coincidence that 2025 is also the year Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein hit the screens?) There are cinematic reasons for this as well. Being stitched together, Frankenstein is aligned with montage. He bears his seams, thus revealing the scheme of their production. Likewise, Jude attempts to expose the seams of AI, whose ideal is to incorporate itself imperceptibly into text and image. “Whenever the program makes something wrong,” he stated in an interview, “we keep it because that’s a kind of special poetics.” [5] But there’s a difference between revealing a glitch and using it to create a meaningful juxtaposition. While Jude’s film does the former, it fails to do the latter. The glitches feel random, poorly timed, and misplaced. The cutaways to AI-generated sequences do little to shift the tone in a satisfying or surprising way. What is worse, given how rapidly AI image generation is advancing, the gimmicks in the film already feel dated.

Radu Jude, “Dracula,” 2025

This is unfortunate since Jude is otherwise a master of montage in the Eisensteinian tradition of letting meaning emerge “through juxtaposition and not through the absolute [value] of pieces.” [6] His past films create contrasts that reveal the humorous, the tragic, the belated, and the absurd aspects of a situation, oftentimes simultaneously. They’ve been rightly compared with the films of Yugoslav director Dušan Makavejev, another filmmaker who has sought to playfully invoke the fascinating powers of the phallus through off-kilter juxtapositions (see the Stalin-dildo sequence in WR: Mysteries of the Organism, 1971). [7] Jude’s films overflow with similar examples: the essay film in the middle of Bad Luck Banging; the fast-paced switching between archival, social media, and art film registers in Do Not Expect Too Much From The End of The World (2023); the cutaways to condo construction projects in Kontinental ’25 (2025); the switch between documentary and fiction in I Do Not Care If We Go Down in History as Barbarians (2019); and so on. These contrasts work because, in each film, they feel precisely timed to the emotional valence of the scene, what Eisenstein might call its tonal or overtonal value. In Dracula, similar contrasts fall flat, if they’re not absent altogether. By focusing on “what the program gets wrong,” Jude’s Dracula ultimately places value on the individual piece at the expense of the juxtaposition. What we’re left with is a series of images and vampire stories that bear little relation to one another.

Perhaps this is an effect of the times we’re living in. Capitalism has entered a stage in which information moves so rapidly that even vampires struggle to keep up. But it would be silly to declare the vampire metaphor exhausted. We have not yet entered a stage of post-capitalism in which the immaterial quality of vampires has lost its sense as allegory. Nor have we exhausted the question of why, despite their embodying capitalism, we continue to desire vampires. This contradiction is worth exploring further, given how vampires also find themselves textually aligned with unrestrained female desire – one that threatens to undermine patriarchal order. Curiously, this question is barely hinted at in Jude’s film, in which all the vampires are equally ridiculous and in which the treatment of female desire never rises above that found in Yorgos Lanthimos’s Poor Things – that is, as a kind of inverted masculine desire.

This question of desire may be put another way. Placing ourselves in the position of those the vampire seduces, we might ask why we desire our own alienation. One answer comes by way of Keti Chukhrov, who argues that such desire is conditioned by our participation in a libidinal economy governed by surplus value. [8] The Soviets did not have vampire movies, or many horror movies to speak of, at least not until Perestroika (think of the undead dictator in Tengiz Abuladze’s 1987 Repentance). The vampire is a manifestation of such surplus value, an excess of jouissance, the locus of ambivalent feelings of desire and repulsion. A desire for our own remediated alienation is thus a basis for the vampire film and novel. It explains why we never see vampires in the mirror, only ourselves.

As allegories for media, vampire tales track the erosion of relationships that once guaranteed the authenticity of artistic products: authorship, indexicality, reference, meaning. These have been distributed across networks and dissolved. Friedrich Kittler made this point in 1982 on the occasion of Jacques Lacan’s death. Under technological conditions, Dracula “has become nothing more than the stochastic noise of the information channels.” [9] The result, to paraphrase Thomas Elsaesser, is a world of universal duplicity, where it has become commonplace to have faith only in fakes. [10]

Radu Jude, “Dracula,” 2025

This point seems ready to hand when it comes to artificial intelligence. And yet, Jude struggles to make it using the vehicle of a vampire film. One reason, as mentioned above, is that the film is too self-aware. It wants to play both patient and analyst. A second reason is that it makes the point so heavy-handedly as to leave nothing to the viewer. Its message thus feels obvious, regurgitated, and force-fed. A third is that the film is unsure of what to do with the technology. It is willing neither to let AI loose, nor to rein it in. Rather, it only wishes to curate a series of funny failures. Finally, the film seems to have a low opinion of the technology it is critiquing. It is more interested in mocking AI using adolescent humor than exploring its creative potential. This translates to its treatment of vampire characters as well – most are pathetic but rarely sympathetic. Such sympathy – the kind one typically finds in Jude’s films – is necessary to make a successful Dracula spoof. Otherwise, all one is left with is a collection of flaccid dick jokes.

And yet, so as not to end on too negative of a note, I will say this: Perhaps Jude’s main success with Dracula is making the viewer feel as if they were in one of his films. The endless advertisement shoots in The Happiest Girl in the World (2009) and Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World; the interminable debate at the end of Bad Luck Banging; the torturous reenactment of a massacre in I Do Not Care If We Go Down in History as Barbarians – all these reveal the way we, as audience members, are trapped inside the spectacle of neoliberal capitalism. If nothing else, Dracula brings this point home in a visceral way. I guess that makes the experience worth it. We can all do with a little bloodletting from time to time.

Radu Jude, Dracula (Romania 2025).

Daniel Schwartz is an associate professor of Russian and German cinemas at McGill University. He is the author of City Symphonies: Sound and the Composition of Urban Modernity, 1913–1931.

Image credits: All © Filmgarten

Notes

| [1] | Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, vol. 1, trans. Ben Fowkes (Penguin, 1990), 342. |

| [2] | Ibid., 256. |

| [3] | Franco Moretti, Signs Taken for Wonders: Essays in the Sociology of Literary Forms (Verso, 1983), 70. Emphasis in the original. |

| [4] | Ibid., 74. |

| [5] | “Radu Jude and Edgar Pêra on the Use of AI in Cinema – Locarno77,” Locarno Film Festival, YouTube, posted August 12, 2024, 11 min., 32 sec., https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A57sZzrUs38. |

| [6] | Sergei Eisenstein, “The Capital Diaries: A New Selection,” October, no. 188 (Spring 2024): 28. |

| [7] | Alan Dean, “Bazin-ga, or RJ: Mysteries of the Organism,” n+1, no. 49 (Winter 2025). |

| [8] | Keti Chukhrov, Practicing the Good: Desire and Boredom in Soviet Socialism (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2020). |

| [9] | Friedrich Kittler, “Dracula’s Legacy,” in Essays: Literature, Media, Information Systems, ed. John Johnston (Routledge, 1997), 79. |

| [10] | Thomas Elsaesser, “No End to Nosferatu,” in Weimar Cinema: An Essential Guide to Classic Films of the Era, ed. Noah Eisenberg (Columbia University Press, 2009), 90. |