„Return of the Blob". David Reisman on Lynda Benglis at the New Museum, New York

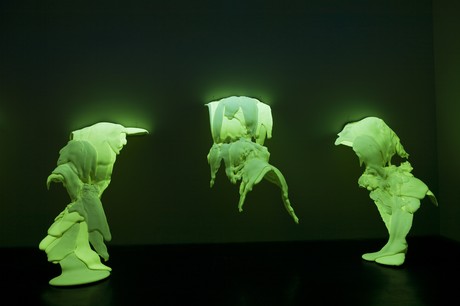

Lynda Benglis, „Phantom", 1971

Blobs, oozes, spills, and puddles are usually associated with accidents – they show our clumsiness, the limits of our self control, or problems with what we’ve created. They’re also made during the first steps in the artistic process – when paint is squeezed from a tube or wet clay is plopped onto a table. In the 20th Century, modernist ideas made it possible to for blobbed, dripped, and poured materials themselves to become recognized as works of art. Making a mess and calling it art is part of an old avant-garde strategy of shocking people into rethinking their assumptions about what’s valuable. Blobs and drips can also be beautiful -- when fluids solidify, their movement is arrested so the result can become a serendipitous and permanent record of transformation. And ambiguous abstract shapes can be the starting point for a variety of associations, as Leonardo da Vinci pointed out and Rorschach ink-blot tests demonstrate.

There’s a science-fiction quality to the blob as art – blobs have lives of their own, and our awareness of the artist’s hand is secondary to experiencing their weird, essential otherness. Blobs are different from more deliberately planned and constructed contemporary art – for example, from the way minimal sculpture is often furniture you can’t use, or that installation art is architecture you can’t live or work in – and in their most basic form, blobs are not funny or angry or freighted with a story to tell. They are, mostly, an almost pure expression of the size, texture, and color of the materials they are created from. Context and explanation can show whether or not a blob is more than the result of an accident or chance, while the blob-as-art might be strange enough to make you rethink some of your basic assumptions about what’s possible and desirable in culture.

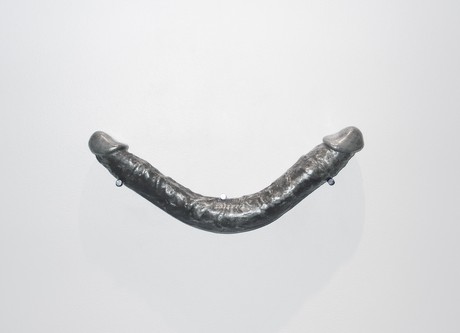

Lynda Benglis, „Smile", 1974

Some of the most memorable art work in Lynda Benglis’s retrospective at the New Museum is blobby – and Benglis, who began her career in the New York art world of the 1960s, shows herself to be a great pioneer of an innovative informality that has an epic, heroic side to it. Emerging from abstract expressionist and pop sensibilities, her early work both embraces and subverts ideas that are frequently associated with Clement Greenberg’s essay “Avant Garde and Kitsch” (1939) and Ad Reinhardt’s ideas about reducing a work of art to its abstract essence– what they saw as distinguishing great, important art from the corny representational art and manipulative mass media that was, and still is, predominant in our society. One of Benglis’s contributions to abstraction was to detach the dripping and pouring associated with Jackson Pollock’s abstract expressionism from the idea of emotional catharsis, using a more impersonal technical approach; contemporary, industrial materials; and pop-inspired, garishly bright colors to make her blobs subversively eye-catching, beautiful, and challenging.

Benglis’s exhibition at the New Museum was not arranged in strict chronological order, and most of the artwork in the exhibition was from the 1970s, with several key works from other decades. While some of her best work has an improvised quality, from the beginning of her career she has also explored other directions in abstract sculpture, including knots, pleated metal, lantern-like paper objects, and irregularly shaped reliefs; and she has also investigated the possibilities of photography, video and installation art. The earliest piece in the show was an untitled vertical lozenge-shaped relief, something not exactly a painting or a sculpture, made from beeswax-covered masonite, dating from 1966. Benglis returned to variations on this isolated relief idea over the years, varying the texture of beeswax; experimenting with the possibilities of cast paper, chicken wire, plaster, and other materials, decorating the surfaces of the objects with gold leaf, glitter, and cellophane. At times, these artworks were totemic and had symbolic overtones, though were never exactly primitivist in intention or execution. For example, even though “Lagniappe” (1978) had an almost anthropomorphic quality, its pink cast paper shape seeming like a kind of body, and the iridescent cellophane on top like hair, it still seemed distant enough from representation to be a goofy comment on both figuration and abstraction. Of all her work, these wall pieces were the most closely related to children’s art, or what Clement Greenberg might have viewed as suspiciously vulgar or kitschy –using an eclectic mix of materials that are bright, shiny, and frequently inexpensive.

Lynda Benglis, „Zanzidae" from the Peacock series, 1979

Some of the most spectacular work in the exhibition was made from poured polyurethane, dating from the 1960s and 1970s. For example, “Night Sherbert” (1968) was made from blobs of colored polyurethane foam and was both radically abstract and cheerfully accessible. “Phantom” (1971) which was originally created for an exhibition at Kansas State University and now shown for the first time in New York City, consisted of five poured phosphorescent polyurethane pieces that jutted out from the wall like splashing water frozen in time, and glowed eerily in a darkened gallery, lit by black lights. Even though “Phantom” was made from industrial materials, the installation evoked natural environments like caves and grottoes. The glowing installation had a kind of magic to it, and reminded me of one of my favorite natural history museum exhibits when I was growing up, a display of phosphorescent minerals whose appearances change under ultraviolet light.

Lynda Benglis, „Primary Structures (Paula’s Props)” (1975)

Benglis’s retrospective showed her to be a thoughtful, searching artist, willing to experiment with new art forms and materials and go off in different directions, even though at times those led to dead ends or indifferent results. For example, the exhibition included a handful of ceramic pieces that were technically interesting (some with twisting, complex shapes), but not as compellingly monumental as some of her work made with less traditional, industrial materials. The “Secret” series (1974-75), framed groups of Polaroid photos arranged sequentially like much other contemporary art of the period, were somehow not as engaging as her more strictly abstract work despite using recognizable images of people and flowers. “Primary Structures (Paula’s Props)” (1975), was a re-creation of an installation from the Paula Cooper Gallery that included a blue velvet cloth on the floor, a ficus tree, a plastic plant, a toy car, small fake columns and a kitsch religious statue that would look at home in a yard in suburban New Jersey. It was a joke about the minimalists’ rejection of pedestals that in some ways foreshadowed 1990s approaches to installation art but was also detour that didn’t lead anywhere in particular. Her early, blurry videos like “The Amazing Bow Wow” (1976) showed that she was around at the beginning of video art, but were hard to focus on in the context of the rest of the exhibition.

Lynda Benglis, „Contraband", 1969

To some degree, artists’ attempts to shock people are as much about generating publicity and notoriety as they are about challenging the status quo. Benglis is known not only for her unorthodox use of materials, but also for a memorably transgressive, over-the-top of advertisement that’s a benchmark for how far artists can go to create their own public images. The exhibition included Benglis’s famous print ad from the November 1974 issue of Artforum International, a photo of her wearing nothing but kitty-cat sunglasses; greasy, naked and mugging outrageously while holding a gigantic, realistic-looking latex double dildo jutting out between her legs, posing like a star of one of John Waters’s early movies. She seems to be saying, “Look at me! I’ll do anything for attention!” While a response to Robert Morris’s S&M-inspired pose for an ad in a previous issue of the magazine, a feminist parody of macho abstract artists and an exercise in bad taste for its own sake, Benglis’s ad was offensive enough that it was denounced by five associate editors of the magazine in the following issue, even leading to Rosalind Krauss’s resignation and founding of the magazine October as an alternative to Artforum. Benglis had made an edition of five sculptures cast from the double dildo called “Smile”, one of which was included in the retrospective.

Benglis is continuing to explore ideas about art that she started out with in the 1960s and 1970s, exploiting the translucence and sculptural possibilities of urethane, rubberized foam, metal, and other media. Some of her recent wall pieces, like “Figure 2” (2007) and “Figure 5”, have irregularly bark-like shapes and textures like grubs or giant larvae, while the underlying abstract shape of “Chiron” (2009) swells from the wall like the top of an alien’s skull or a giant, pregnant orange belly. Benglis’s restless investigation of artistic form and new ways of making art with industrial materials is still fresh; it still has the capacity to surprise and suggest new opportunities for art and culture. At the same time, her giant blobs of polyurethane that once seemed aggressive and strange now have an almost timeless and classic beauty.

“Lynda Benglis”, New Museum, New York, February 9-June 5, 2011