DISCOMFORT READING Alice Blackhurst on Hervé Guibert’s short prose

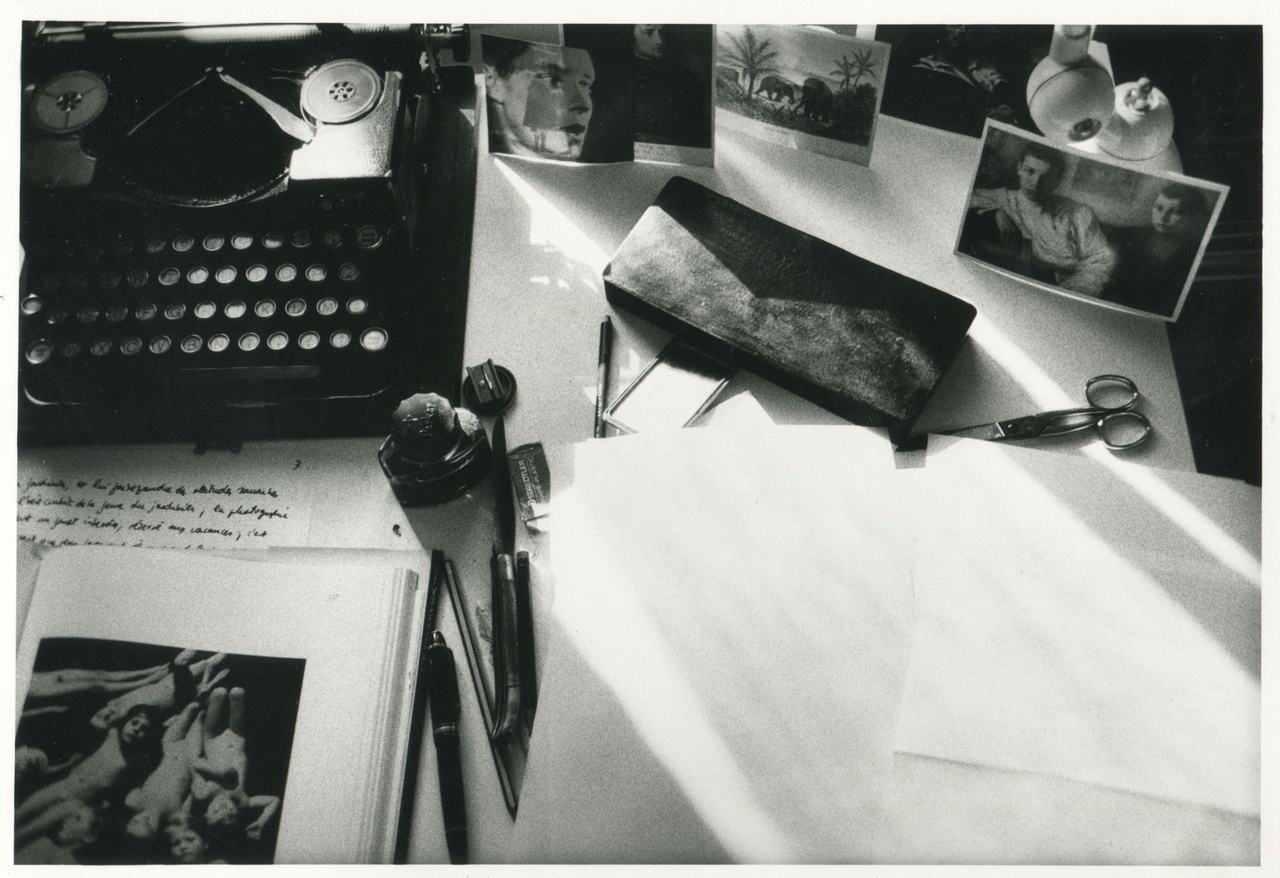

Table de travail, 1985

In Cytomegalovirus: A Hospitalization Diary (1992), a text published following his death at 36 years old, Hervé Guibert recounts seeing a man splayed on a gurney in a hospital ward and feeling turned on for the first time in months. The return of sexuality, in the midst of brutalizing treatment for AIDS, vivifies and thrills him. “When I rediscover an erotic emotion, it’s like finding a bit of life while drowning in this death bath,” [1] he writes.

Militantly candid and devoutly unsqueamish, a refusal to present as a penitent ‘sick person’ sanitized of all excess and Eros fast-tracked Guibert to the vertigos of literary fame in the 1990s, now commemorated in two new English-language translations published by Semiotext(e) this spring. Though already established as a cosmopolitan photography critic for Le Monde and photographer in his own right, trafficking in various Parisian intellectual milieux and boasting an expansive repertoire of decorated lovers, it was his electric, gaunt appearance on the French cultural talk show Apostrophes, where he spoke to his ‘sealed’ fate without regret or shame, that made him something of a spectacle. Playing to the press’s appetite for an overnight sensation, he became, almost immediately, a telegenic icon for a new, unstinting virus that compelled as much as it estranged.

The account of his diagnosis, To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life (1990), an early example of French autofiction in its enigmatic braid of fact and fiction, exploited blunt confession as a portal to desired amnesia. “I wrote in order to forget,” he confirmed, in the famous interview for Apostrophes. In part, To the Friend registers as a vengeful diatribe against the crowd of swindlers who paraded promises of vaccines before Guibert rapidly succumbed to AIDS’s devastations. But it is also an elusive snapshot of the enigmatic death of his friend “Muzil” – a skimpily disguised Michel Foucault –who did not disclose his own contraction of the disease. Though generally well-received, a less enraptured corner of the media called out the contentious ethics of this self-articulated “exorcism;” this audacious feeding off the Other to console the disappearance of a self in space and time.

In spite of the immediacy of To the Friend’s literary and commercial impact, a desire to provoke, unsettle, and exfoliate the varnished platitudes of normal life rages throughout Guibert’s varied and prolific corpus which he cultivated, alongside his image work, from his early twenties. A collection of these heterogeneous prose offerings, recently translated by Jeffrey Zuckerman, makes a case for Guibert’s literary value before it was imprinted by the notoriety of illness, or before it was put to the (impossible) service of lending an epidemic a human face. Hurtling between diary entries, prose poems, travelogues, novellas (récits), and what is classified as more conventional ‘short stories,’ the collection autopsies the breadth of Guibert’s range; his aptitude for genre work in excess of the addictiveness of ‘memoir’ (to which he is too often simmered down). Though the chosen title of the publication, Written in Invisible Ink (2020), seems to gesture to the overlooked and clandestine, or to what may have evaporated from the canon, its equivalent in French of encre sympathique or ‘sympathetic ink’ has a warmer, more materially concrete purchase: suggesting that which requires pressure from heat or touch to be revealed.

Although the collection is not disciplined entirely by chronology, it logically opens with Guibert’s first published novella, Propaganda Death (1977), a rampant wunderkammer of illicit trysts and objects, where the writer’s furious desire to make an exhibition of himself and his (eerily predicted) mortality is registered in bracing, incandescent prose. On the question of dying, Guibert-as-narrator boldly announces: “We try to drown it in disinfectant, to suffocate it in ice. But I want to let its powerful voice ring out and sing, a prima donna. Put on this extreme, immoderate show of my body, in my death.” [2] The statement’s petulant directness is a microcosm of the writer’s bald theatricality, his deliberately stoked inflammations. Sparking a lifelong attentiveness to the visceral entanglements of sex and mortal flesh, the short work bristles with what novelist Marie Darrieussecq, who wrote her doctoral dissertation on Guibert, calls “rancid” [3] fucking, or carnal acts so floridly explicit they inspire a rush of compound neologisms: “fuckjuice,” “glorious gravy,” “dick-lusciousness” (which must have been a headache to translate). Though such flourishes somewhat betray the age of their creator (Guibert was just 21 years old when Propaganda Death was published), Zuckerman, in his poised Translator’s Note, incites the reader not to set the text aside as “juvenilia.” [4] Instead, he wants us to see in Propaganda Death’s digressions the initial flares of a writer tirelessly consumed by illness, confession, other men, and a promiscuity of literary forms.

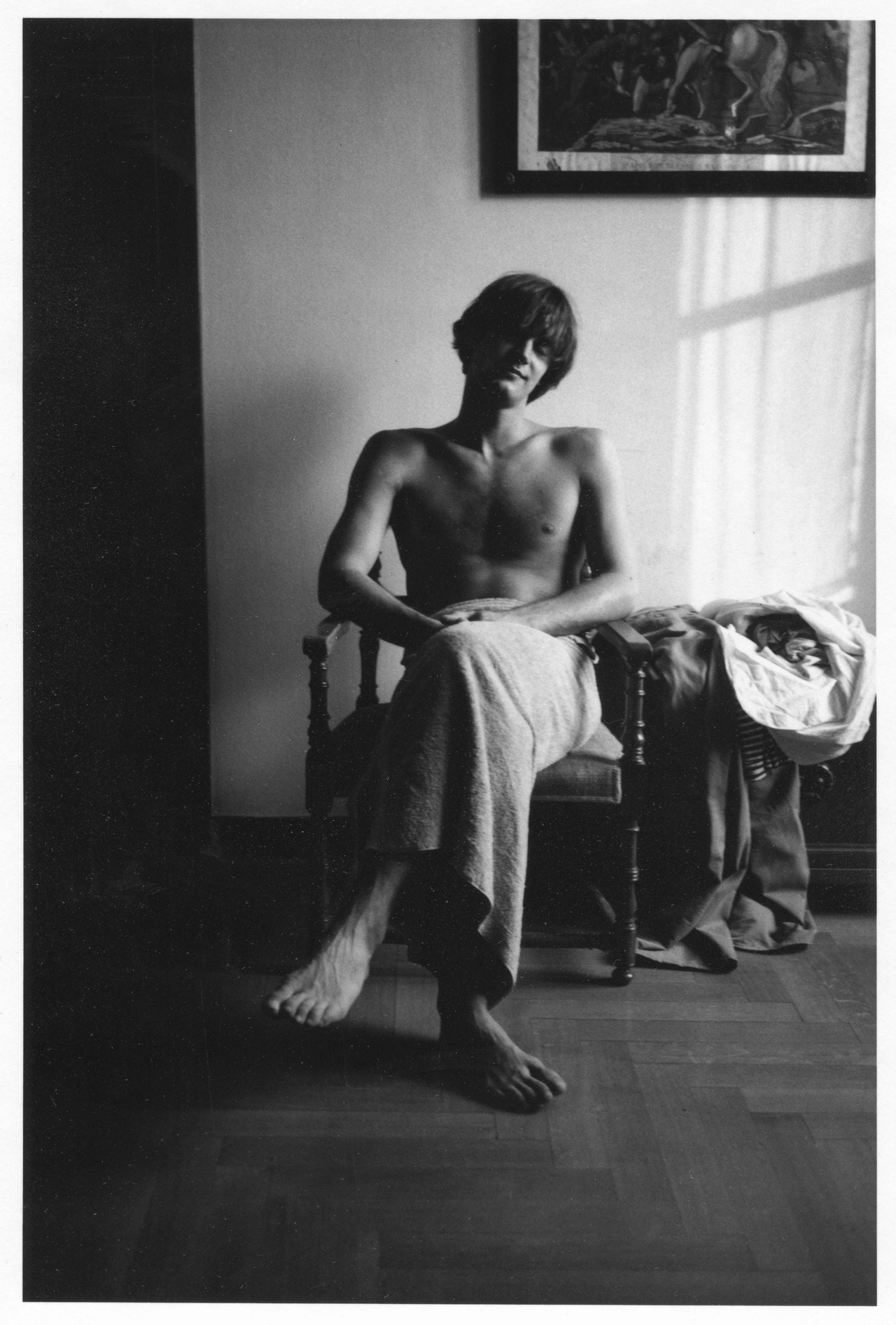

Thierry Jouno, Palermo, 1980/1981

In his Apostrophes interview, Guibert, responding to a question about To the Friend’s long, occasionally clotted sentences, draws a parallel between the deliriousness of his illness and his prose’s tendency to “feverish enjambments.” [5] Yet, faithful to his journalistic training’s sensitivity to brevity and bloodlust for a pacy story, his clauses can be telegraphic and incisive, too. Another highlight of the collection is Vice (1991), a series of page-long inventories of clinical props and medical paraphernalia – masks, gloves, ventilators – which chill both for their uncomfortable proximity to the scarcities of the current COVID-19 crisis and their forensic, emotionally neutered tone. Originally illustrated by accompanying photographs, in this edition all adjacent imagery has been strikingly omitted, nodding to Guibert’s fixation on the specter of the ‘absent image’ throughout his work (an obsession shared by writers similarly catalyzed by visual techniques such as W. G. Sebald and Marguerite Duras).

Given the preponderance of bodily expulsions and excretions in Invisible Ink, the cerebral, almost elegiac atmosphere of one of the collection’s final stories, “A Man’s Secrets,” feels like a substantial detour; something of a watershed. It is here that readers can immerse in the first sketch of the author’s thoughts about his friend and rumored lover Michel Foucault’s death; despite the singularity of his own work, he never managed to exhume this ghost from the margins of his prose. Despite orchestrated moments of deliberate vulgarity and provocation – Guibert can’t resist, for example, zoning in on how the evoked “philosopher-child” chose a cloth in which he had “made love” with one of his male partners, from his “mother’s trousseau,” no less, to bury his corpse [6] – the dominant tone is, uncommonly, one of sobriety as the story gathers deft (and now painfully acute) meditations on the ostracizing force of AIDS as a disease: “Above all the name of the plague was not to be spoken, it was to be disguised in the death records, false reports were given to the media. His friends could no longer see him, unless they broke and entered: he saw a few of them, behind their plastic-bag-covered hair, masked faces, swaddled feet.” [7]

In the raging epicenter of our current, very different pandemic, it is tempting to yield numbly to suggestions for narcotizing ‘comfort reading,’ or to be steered towards books that might blunt the edges of this free-falling global catastrophe. Guibert’s spikiness, his unmollified intimacy with organs, viscera, and the specter of the most unsightly deaths, is a stark riposte to such prescriptions. His refusal to desexualize, aestheticize or reduce to ‘relatability’ the seriously ill person might for some prove difficult to assimilate, but his commitment to exposure and to exhibition is instructive when the instinct might generally be to muffle, veil, not want to see. In Invisible Ink’s crystalline yet scalding compositions, Guibert’s channeling of the ‘indicible’ or the unsayable, on the cusp of the AIDS crisis, grimly X-rays the indifference and alienation still, decades later, at the core of our ‘new normal.’ Across various, dazzling formats, his work probes what we permit ourselves to be exposed to, and whether we possess the stamina to keep on looking. In Zuckerman’s English rendition, the distilled quality of the translated prose further sharpens this endurance: the invitation to engage, and not to turn away.

Hervé Guibert, Written in Invisible Ink: Selected Stories, translated by Jeffrey Zuckerman (South Pasadena, CA: Semiotext(e), 2020).

Alice Blackhurst is currently a Junior Research Fellow in French and Visual Culture at King’s College, Cambridge. Other writing has appeared in n+1, the Los Angeles Review of Books, The Paris Review Daily, and Another Gaze.

Image credit: Estate of Hervé Guibert, Paris and Callicoon Fine Arts, New York

Notes

| [1] | Hervé Guibert, Cytomegalovirus: A Hospitalization Diary, trans. Clara Orban (New York: Fordham University Press, 2016), p. 69. |

| [2] | Hervé Guibert, “Propaganda Death,” in Written in Invisible Ink: Selected Stories, trans. Jeffrey Zuckerman (South Pasadena, CA: Semiotext(e), 2020), p. 28. |

| [3] | Marie Darrieussecq, “Guibert’s Ghost,” Tin House, January 13, 2015, https://tinhouse.com/guiberts-ghost/. |

| [4] | Jeffrey Zuckerman, “A Note on the Chronology,” in Written in Invisible Ink, pp. 19–23, quote p. 19. |

| [5] | Hervé Guibert, Apostrophes interview, Archiv INA, March 16, 1990, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=en9OWEvf_Cw&t=1s. |

| [6] | Hervé Guibert, “A Man’s Secrets,” in Written in Invisible Ink, p. 255. |

| [7] | Hervé Guibert, p. 254. |