IT’S LIKE ARGUING WITH A BRICK WALL Elliot Gibbons on Martin Wong at Camden Art Centre, London

“Martin Wong: Malicious Mischief,” Camden Art Centre, London, 2023, installation view

“It’s like arguing with a brick wall,” one might exclaim when attempting to get through to someone who refuses to listen. In “Martin Wong: Malicious Mischief” at London’s Camden Art Centre, this Anglophone expression constantly came to mind, and that was not simply because bricks form a prominent part of Wong’s visual lexicon. This saying came to mind, instead, from the common understanding, as Agustín Pérez Rubio points out in the exhibition catalogue, that Wong’s painting is often thought of as “silent painting” from his adoption of sign language gestures. [1] Wong’s use of sign language, however, or even other instances where he depicts lived experiences that were not his own, can indeed speak quite loudly to current debates. Particularly given that the exhibition comes at a time when there has been a noticeable return to figuration in painting, in addition to a lively contemporary discourse around the politics of representation. The exhibition itself appears to stay silent, forgoing a consideration of these debates within the interpretation of Wong’s corpus.

Camden Art Centre is the third European venue to host the touring Martin Wong retrospective, surveying the life and work of the late Asian American artist. For this exhibition, the Centre has expanded its typical floorplan through joining together two of its smaller galleries, thus each of the latter six rooms are accessed via the first, which focuses on the artist’s early years. The layout consequently positions Wong’s so-called beginnings on the West Coast, including his involvement with the guerrilla theater troupe The Cockettes (later known as the Angels of Free Light Theater) and his travels to Europe, India, and Afghanistan, as foundational to the development of his practice. Each further room, painted in distinct and bold colors, concentrates upon a loose chronological period, while the final room displays on a loop the video portrait of Wong by filmmaker Charlie Ahearn, taken a year prior to Wong’s death from HIV/AIDS complications in 1999.

“Martin Wong: Malicious Mischief,” Camden Art Centre, London, 2023, installation view

One of the works in the first gallery is catalytic for how one could begin to generatively look at Wong’s figuration today. Cockettes in Pearls of Shanghai (1970) is a framed print of a poster Wong had designed for the radical theater group. Pearls of Shanghai happens to be The Cockettes’ most controversial performance, owing to its performers being in yellow-face and its heavily orientalized sets. The poster’s focal point is a hippo with its mouth furiously agape, stars emanating out from its open orifice. Text crowds around the illustration, advertising the play in various types of lettering, including Chinese calligraphy. Julia Bryan-Wilson, in her book Fray: Art and Textile Politics (2017), has interestingly noted the questions that arise around his relation to the group’s performances in light of Wong’s own position as a Chinese American, and the fact that he contributed to the theater’s orientalized productions. [2] Both the wall text and the title panel, choose not to elaborate on the significance of this poster – a missed opportunity to consider Wong’s irreverent relationship to his own identity. This irreverence is integral to understanding the complexity of his practice. His own lived experience as a gay Asian American often led to him feeling like an outsider, and his practice was a means of creating a shared language across difference.

The second room, with dark navy walls, considers Wong’s move to New York in 1978, featuring important works such as Psychiatrists Testify: Demon Dogs Drive Man to Murder (1980). Swelling off the wall, with edges bowed, the canvas is almost sculptural. This painting, Wong explained, was inspired by the World Weekly News headline he read from a newspaper stand at a subway station moments prior to receiving a “Hello, I’m Deaf” card aboard the train. [3] The reverse of the card detailed the American Sign Language (ASL) alphabet. Hence, the painting spells out the headline in fingerspelling, each hand emerging from the cuff of a white shirt with a ruby gem cufflink. A border of detailed red bricks frames the fingerspelled headline upon a black background, with the translation of the fingerspelling along the edge; running along the bottom, a depiction of a plaque exclaims “Painting for the Hearing Impaired.” Wong was a hearing person; his painterly adoption of sign language is one significant instance where he imbibes experiences that were not his own. Interestingly, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, the previous host of “Malicious Mischief,” provided a reproduction of the original “Hello, I’m Deaf” card for visitors to take around the exhibition. The iteration at Camden Arts Centre, on the other hand, lacks this card.

“Martin Wong: Malicious Mischief,” Camden Art Centre, London, 2023, installation view

In order to begin to understand the complexity of this disparity amongst institutions providing a handout with a translation of the ASL alphabet, there has to be an understanding that sign language is its own language with different formations throughout the world. For instance, there is a stark difference between American Sign Language and British Sign Language (BSL). Although American and British written and verbal language is almost the same, those who understand ASL are unlikely to grasp BSL, as letters in BSL are signed with both hands rather than one. As Sofie Krogh Christensen has explained in the catalogue, a key component of ASL is the physical and visual act of signing, such as facial expressions, which is completely lost when Wong fingerspells out text sign by sign, letter by letter. [4] Despite Wong proclaiming the painting Psychiatrists Testify was “for the hearing impaired,” those who are deaf and use ASL are not significantly more adept to view these paintings than hearing audiences are. In Germany, those who are deaf or hard of hearing would use German Sign Language (DGS), thus the card provided at KW Institute may have been intended to benefit DGS users unfamiliar with ASL even though it had all the workings of a gimmick – the similarities between the fingerspelling alphabets of ASL and DGS would indicate the latter. Nevertheless, to not provide the handout, as Camden Art Centre did, is to further abstract these paintings for local deaf communities who would be users of BSL and unfamiliar with ASL.

With or without the card, there is a complexity to Wong’s use of fingerspelling. Psychedelic Triptych (1988), shown in the third room, is a much later fingerspelling painting, which abstracts the form of the hands, an aestheticization of sign language and Kufic script. The canvas is split into three sections: black, green, and blue. Elongated and clearly out of proportion, the hand gestures are now almost unreadable. But, as in Psychiatrists Testify, the letter translation is included, albeit inside the cufflink of each hand. In these works, the troubling nature of his painterly play with ASL is evermore present. His gesticulating hands become, as Krogh Christensen posits, “iconographic signatures.” [5] Wong abstracted a language he was barely literate in, so he could find his own script, similar to how his graffiti artist friends would invent their own distinct “tags”. Though his iconographic script might have been well intentioned, giving voice to fellow underrepresented communities as discussed above, it glosses over the more embodied nature of using ASL. The medium of painting, specifically figural painting, has intrinsic limitations though, one of them being that the animacy of a subject cannot ever fully be translated onto a two-dimensional plane. But in our contemporary moment when accessibility is the curatorial impetus for a number of group shows, or when new provisions such as sign-language video introductions are increasingly common in institutions throughout Europe, there is an absence of criticality when it comes to Wong’s uptake of ASL (aside from the mere mention of his misuse of sign language in the catalogue entry by Krogh Christensen or the FileNote essay by scholar and curator Solomon “Zully” Adler). Instead of posing the question of whether or not he had the right to adopt ASL into his visual repertoire, there should be a more trenchant consideration of the stakes involved in his semiotic play, such as a more accurate understanding of sign language.

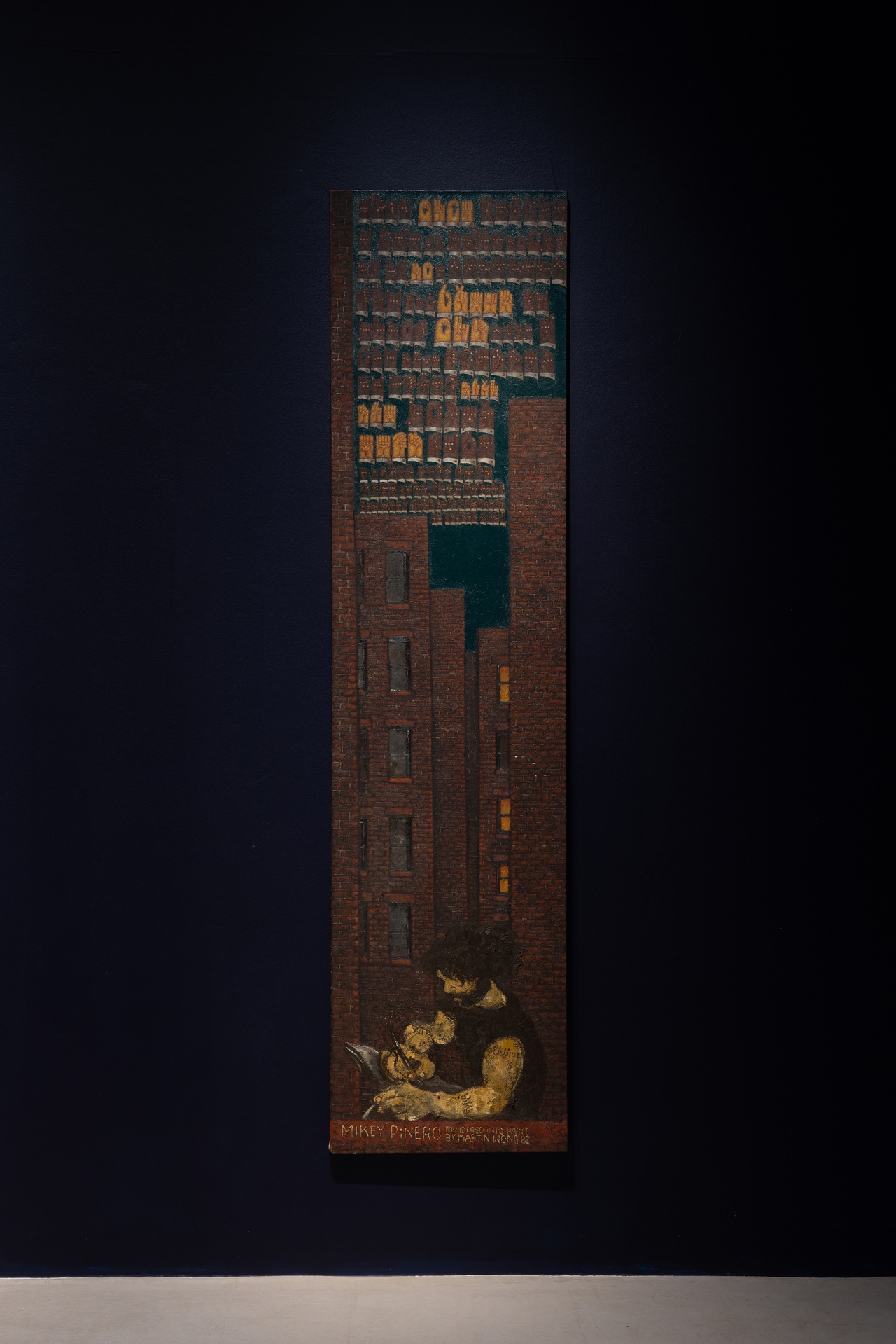

Martin Wong, “Portrait of Miguel Piñero,” 1982

Wong’s use of gesticulating hands within his paintings is not the only instance in the exhibition where one is confronted with his representation of lived experience that he was unable to call his own. Stemming from his relationship with the Puerto Rican poet and Loisaida resident Miguel Piñero, who was incarcerated on numerous occasions, Wong became fascinated with prisons and the homosocial aspects of those spaces. He produced several paintings depicting Piñero’s cellmates, frequently loaded with homoerotic undertones, such as Come Over Here Rock Face (1994) shown in the bright teal fourth room. Stood with folded arms is a white security guard, while behind grey prison bars is a brown-toned figure with a clothed yet plump buttock. In the right-hand corner of the painting, the title is extended to include “AND SUCK MY DICK.” The wall text refers to this series as a kind of “critical appropriation,” for Wong depicts moments of eroticism in “infrastructures that maintain hegemonic power,” which were known to be hostile toward homosexuals. Still, the very real and harsh reality of the carceral system becomes eroticized in these works. Given that Wong had never been imprisoned, other than for one night as he had claimed, there is again a complexity that feels as though it could have been further unpacked by the institution. [6]

The exhibition, catalogue, and separate File Note essay avoids putting Wong’s body of work in direct dialogue with these contemporary debates. Of course, to look to the past with a contemporary set of questions poses its own set of issues. Even so, Wong’s position as an outsider who faced societal oppression, as did the communities he depicted, moves the debate away from the treacherous question of who has the right to represent a community to one that can focus on the stakes of what may or not have been occluded by his mark-making. Wong’s adoption of ASL is a prime example: while he gives visibility to deaf or hard-of-hearing communities, he also obscures sign language for hearing and non-hearing viewers alike. But complexities like this were ignored within the exhibition’s interpretation, thus, it can feel like arguing with a brick wall.

“Martin Wong: Malicious Mischief,” Camden Art Centre, London, June 16–September 17, 2023.

Elliot Gibbons is a writer and curator based in Essex, United Kingdom.

Image credits: Courtesy of the Martin Wong Foundation, photos Rob Harris

Notes

| [1] | Agustín Pérez Rubio, “It’s Not Really What You Think: Martin Wong and the Recreation of the Sociopolitical Landscape of Loisaida” in Malicious Mischief: Martin Wong (Berlin: KW Institute for Contemporary Art; Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther und Franz König), 135. |

| [2] | Julia Bryan-Wilson, Fray: Art and Textile Politics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017), 57. |

| [3] | Sofie Krogh Christensen, “A Cosmos of Codes: The Languages of Martin Wong,” in Malicious Mischief: Martin Wong, 87. |

| [4] | Ibid., 88. |

| [5] | Ibid., 87. |

| [6] | David Getsy, “Bricks and Jails: On Martin Wong’s Queer Fantasies” in Malicious Mischief: Martin Wong, 181. |