Jack Gross on Ed Lehan at Reena Spaulings Fine Art, New York

Twentieth century critiques of contemporary life frequently focused on banality. In Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We, for example, or Adorno’s Minima Moralia, or the Wachowskis’ The Matrix, we are shown organized society voiding some essential marker of the vitality of lived experience – numbers are given instead of names, leisure time becomes the requisite social labor of “networking,” days are spent in office cubicles. In Ed Lehan’s first New York solo show, “Return to Problem,” it is perhaps this refrain that was concretized in the drop ceiling that the London-based artist had installed at Reena Spaulings’ Lower East Side gallery.

Seldom seen in art spaces, the ceiling was the cheap kind you’d identify with corporate, educational, medical, or governmental locales, a design detail whose aesthetic function is typically to hide the networked infrastructure that lies behind it (electrics, HVAC, telecommunications systems, etc.), and whose form (interchangeable tiles) permits infinite, inconsequential reconfiguration and replacement, not unlike the boards of Theseus’s ship or a floor of Fordist workers. The ceiling is part of a whole that extends well beyond any particular room, a kind of architectural climate control uniting built interiors in blandness. Such signification might ring as outmoded in 2015 – where uniformity is dressed up as difference and the headquarters or “campuses” of the tech behemoths that dictate the terms of our sociality look more like theme parks than Neo’s late-‘90s cubicle office. And yet, its logic is continuous with that of “junkspace,” as Rem Koolhaas has termed our building-less architectural landscape – one characterized as “additive, layered, and lightweight, not articulated in different parts but subdivided,” the space in which “we work harder … marooned in a never-ending casual Friday.” [2]

Returning to Lehan’s installation at Reena Spaulings, it should be noted that the gallery is split, with the main art viewing taking place on a raised wood platform. Critics have likened this arrangement to a stage across which, during each exhibition, a different social theater unfolds. By condensing the height of the room and (at least symbolically) the activity the space contains, Lehan exaggerated that dynamic.

It’s on this “discussion island,” as the press release puts it, that the “neutral, possibly weak move” of “repeating relational aesthetics” took place. For the opening, mojitos were mixed and served in large plastic garbage bins and paint buckets. These sat, emptied of the drink, on the otherwise bare platform for the remainder of the exhibition, with only a couple stacks of plastic cups indicating to later viewers the bins’ purpose in the show. If this return to relational aesthetics and its economy of experience seemed lame, that was not only the point, but one that Lehan emphasized by staging the action under the ceiling’s bleak cover: the dreary, ironically liberatory ‘fun’ of Mojito night served as testament to the banality of the lives of art people.

In this, “Return to Problem” seemed to play directly with some of the issues laid out in Merlin Carpenter’s “The Opening” series (the first iteration having been staged at Reena Spaulings in 2007). In Carpenter’s show, a near-empty gallery was equipped for a cocktail party, which, near its end, Carpenter “interrupted” by painting. Across several white canvases that hung on the walls, he wrote lines like “Die Collector Scum,” and, “Relax, it’s only a crap Reena Spaulings show.” Lehan’s arrangement was a markedly classed down version – the alcohol wasn’t poured into glasses over a white tablecloth, but scooped from the plastic containers. And Lehan’s reduction of Carpenter's piano-soundtracked cocktail affair had no correlating crisis-finale moment; “Discussion Island” isn’t interrupted by brash callouts.

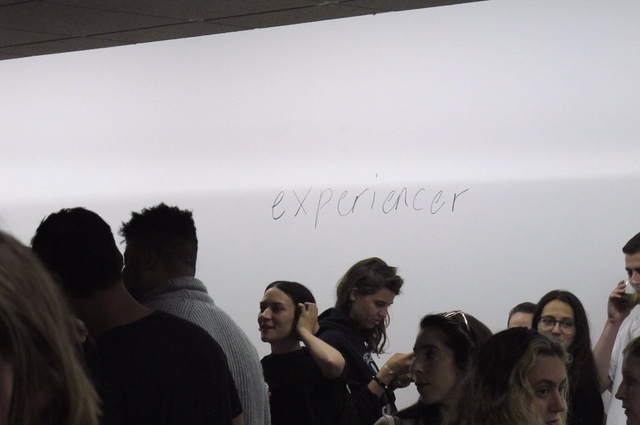

The third and most potent element of Lehan’s sparse show was a word scrawled on the gallery’s wall: experiencer. The perfectly awkward handwriting – messy and large – left a punkish human trace (again, reminiscent of the writing Carpenter left on his “Opening” paintings). But with Lehan, the more open-ended Experiencer – not the artist, nor necessarily the viewer – was the protagonist: a character type to populate the insipid confrontation between dropped ceilings and sugary cocktails. Experiencer replaces Consumer as s/he takes over as the paradigmatic (aesthetic, relational, or otherwise) consumer-subject of liberal market democracies. In this sense Lehan’s script played on Carpenter’s set-up by neutralizing its vertical relations. With “Return to Problem,” the artist’s act is not at the center of the exhibition. Rather, Lehan mimicked the maker’s mark but left the authorial role as an “available subject position.” But, to me, “Experiencer” didn’t register as “available” at all: the scribbled word read like a prescription, one mutually enforced by every person in the room. Visitors were, without effort, bound to the role. The experiencer was there to look, to drink, to witness – to generate vitality (value) for the artist, the gallery, themselves, the economies in which they exist.

The “weak" and “neutral” moves of Lehan’s show (a few drinks, an innocuous ceiling) are – like the racism of politically impotent geriatrics or the myopia of drunk bohemians or the contrived openness of art world "platforms" – anything but. To critique the banal is to show how the atmospheric conditions that go unnamed are exactly not neutral – like drop ceilings, Cuban cocktails, and experiencers. While the warped vortex of scene-referentiality and socioeconomic truisms in Lehan’s show are genuinely not uninteresting, it’s hard to feel excited, or even convinced, by this kind of criticality. In the return to this set of problems, what is offered? A funhouse mirror by which art people can see themselves reflected, bleakly, back at them? Or, to steal a question from an early relational/Bourriaudian aesthete Liam Gillick: "What does the contemporary produce other than a complicit alongsideness?" [4] Criticality that follows on the suggestion to “feed the art world to the art world” [5] simply restates (with a wink or a frown) the impossibility of an outside – an approach that seems to be, like the objects of its own critique, unconditionally banal.

Notes

| [1] | Ed Lehan, "Return to Problem," Reena Spaulings, New York, 2015. Installation view. Photo: Joerg Lohse |

| [2] | Rem Koolhaas, “Junkspace,” in October, Vol. 100, 2002, pp. 175-190. |

| [3] | Photo: Joerg Lohse |

| [4] | Liam Gillick, “Contemporary art does not account for that which is taking place” http://www.e-flux.com/journal/contemporary-art-does-not-account-for-that-which-is-taking-place/. |

| [5] | http://www.merlincarpenter.com/tail.htm |