Fatima Hellberg on “je suis féministe” at Penarth Centre, London

“je suis féministe,” at Penarth Centre, London, invitation

It doesn’t have to be so nice, that’s the bottom line. In Sarah Schulman’s The Gentrification of the Mind, a psychic and material double bind is articulated – she speaks of the multiple ways in which gentrification produces subjectivity, and its normalising impact on desire. It’s a personal memoir and rant, reflecting on loss, and the need for a politics of space and of gender, which does not follow a line of arrival, or comfortable resolution. There is a coupling there between questions of survivalism and a desire for less contained identity politics that can be sensed in the recent exhibition “je suis féministe,” staged during an evening in South London. Articulated as a response to a sudden availability of usable space, and as an outcome of a number of years of conversation between close friends, the show brought together 28 artists – a group consisting mostly of London-based, female artists. The invitation to the show made reference to the title – taken from that of a 1976 television interview with Simone de Beauvoir, “Pourquoi je suis féministe?”; drawing a direct line between definition and self-identification – coupled with an image of a group of teenage girls smoking by a field, joined in a sense of unabashed camaraderie. More an attitude than an articulated framework, this sensibility seemed to be carried forth in the works themselves, most which operated on a minimal economy of time and means – assemblages, short video works shown directly on laptops, text-based responses found or fragmented in form.

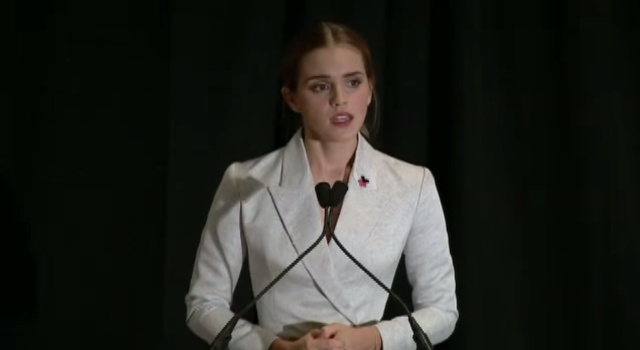

Emma Watson speaks on behalf of the HeForShe campaign, United Nations, New York, September 22, 2014

Around the time of the opening, there had been two particularly striking engagements with feminism as self-identification. Emma Watson’s UN speech, which extended a “formal invitation to men” that completely glossed over any of the advantages built into patriarchal powers, and Karl Lagerfeld’s perverse appropriation of a “feminist protest march” as part of the Chanel S/S 2015 Collection. The feminism articulated within these public stagings arrives imbued with a peculiar brand of optimism. It’s a vocabulary of individual performance and self-actualization intimately wrapped up in the value systems of contemporary capitalism. This reading in no way comes with a desire to undermine what are often important mass medial attempts to extend an awareness of gender politics, but rather, to note the importance of forms that do not operate within a gentrified logic – of the necessity to also give space to discomfort, to the unresolved relationships that can arise when a politics is deeply felt.

Melika Ngombe Kolongo, Give Them Witch They Want, 2014

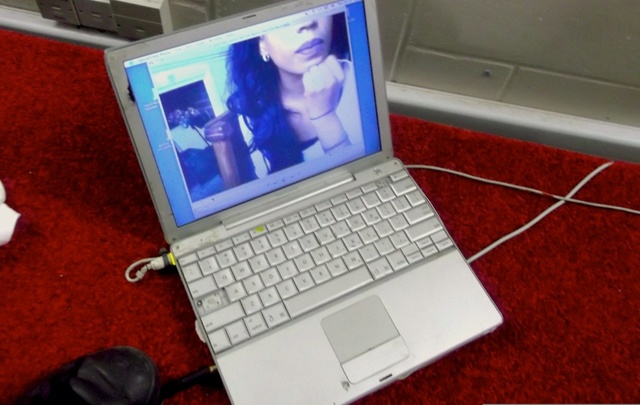

What “je suis féministe” did was to articulate a feminist space that did not deliver. Within this proposition, certain formulations of vulnerability and intimacy were also opened. It was a sensibility that could be felt in Adam Christensen’s performance that night – the starkly lit meeting room of a space, and the somewhat awkward transitions between his sardonic and explicit narrative interspersed with stop-and-start fragments of dance and music – which carried as much defiance as it did tenderness. Similarly operating in a register of personal politics and ambivalence was the short film of Melika Ngombe Kolongo. The looping work, Give Them Witch They Want, draws on a YouTube aesthetic of the video-based selfie, yet awkwardly cropped – a self-observing halved face – whilst the sound element, a scratched doomcore track, continues on repeat. It’s a type of representation that resists resolution, moving across shades of narcissism, boredom, and subtle violence. What also came through in most of the works, was a more or less clearly articulated space of sex – one ranging from the explicitly pornographic, and admittedly disorienting images of Dan Mitchell and of Rihanna Turnbull, to the more subtle tension of intimacy transmitted via pieces by Patricia L Boyd, Georgie Nettell, and Morag Keil.

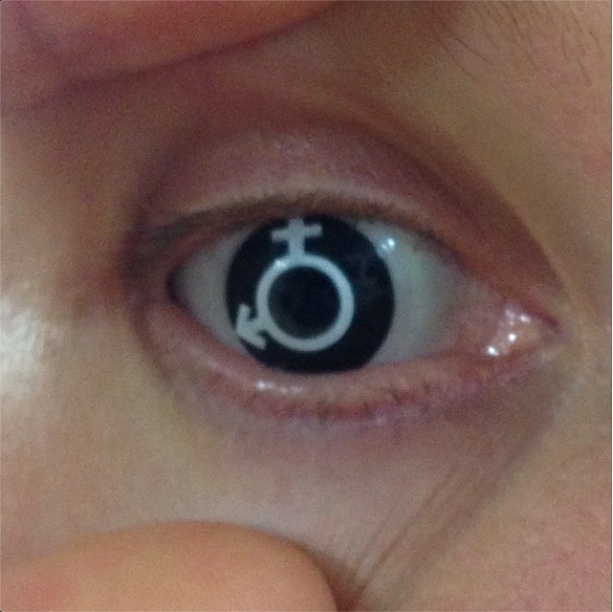

Sidsel Meineche Hansen, Non-binary Eye (the potential is immense), 2014

Such fascination with the libidinal sits interestingly in light of the de Beauvoir link and with her own articulation in the later Alice Schwarzer interviews that this very space, a space of sex, and her own sexuality was remaining as an underexplored lack in her work. What this more tentative, and at times unresolved approach to gender representation seems to touch upon is a feminism that also is a feeling – one that impacts your perception and politics – and critically, which you feel with others.

“je suis féministe,” organized by Morag Keil, Patricia L Boyd, Georgie Nettell, and Lena Tutunjian, was held at Penarth Centre, London, October 4, 2014. Artists: Rachal Bradley, Harry Burke, Adam Christensen, Susan Conte, Jana Euler, Nadine Fraczkowski, Manuela Gernedel, J A Harrington, Onyeka Igwe, Marie Karlberg, Morag Keil, Ed Lehan, Patricia L Boyd, Sidsel Meineche Hansen, Dan Mitchell, Marlie Mul, Melika Ngombe Kolongo, Georgie Nettell, Lucy Parker, Josephine Pryde, Ash Reid, Matthew Richardson, Joanne Robertson, Haydon Saunders, Gili Tal, Rihanna Turnbull, Lena Tutunjian, James Whittingham.