BORING PAINTING Joel Danilewitz on Ull Hohn at Greene Naftali, New York

"Ull Hohn: No Great Mysteries," Greene Naftali, New York, 2023, installation view

Greene Naftali’s recent exhibition of Ull Hohn’s work, “No Great Mysteries,” curated by the gallery’s senior director Monika Senz, underscores the late German artist’s interest in painting as a site of banal pleasure. The show features a suite of untitled feces-like reliefs – eight 20 x 26 in. panels covered in a brown, excremental plaster – as well as a series of five small landscapes referencing American painter Bob Ross, and other untitled works of splatter-enamel that invoke – and complicate – the style of Hohn’s contemporaries. Hohn lived with HIV/AIDS, and during his career he made subtle responses to the violently passive, neoliberal culture of the 1980s, which have been shown around the world following his death in 1993. The selection at Greene Naftali by necessity reiterates aspects of earlier Hohn shows at Algus Greenspon and American Fine Arts, and a handful of previously unseen works continue to signal his interest in boredom as a potential aesthetic register.

Hohn’s landscapes at Greene Naftali illuminate a throughline between the motivations of Gerhard Richter and Bob Ross, contrasting the former – the father figure of neo-expressionist art – with the latter – contemporary painting’s beloved yet estranged uncle. Hohn’s 1993 Untitled series highlights notions of taste by pairing Richter with Ross, who is a celebrated emblem of “lowbrow” American genre painting. Ross’s televised landscape painting demonstrations gained huge audiences who could appreciate their accessibility and his comforting presence. Whether out of boredom or obsession, Hohn braids these two styles in his work throughout the show, foreclosing the audience’s pursuit of rigid taste through scandalously mundane, terrestrial scenery.

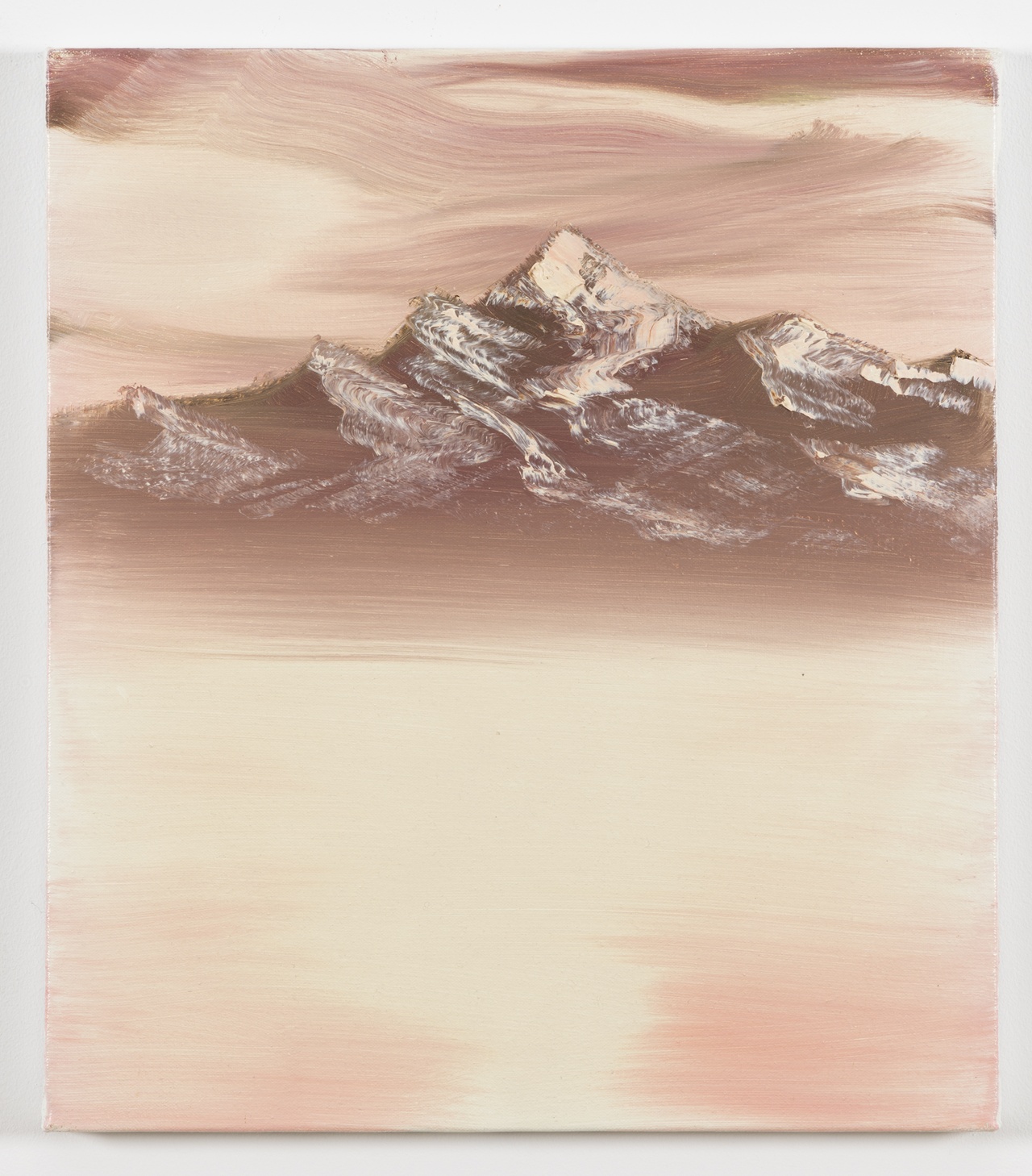

Ull Hohn, "Untitled," 1992-93

For a 1993 solo exhibit at Colin de Land’s gallery American Fine Arts (AFA), Hohn himself had commented on Ross’s pedagogy and provided a further appropriation of Ross’s philosophy, citing a quotation from him: “There are no great mysteries to painting. You only need the desire to paint, a few basic techniques, and a little practice.” [1] Hohn conflated Ross’s demonstrations with what was expected of high art at the time, through smudges and smears, deploying aspects of Richter’s quotidian facture in provocatively conventional settings such as a remote cabin or a gentle stream. Untitled (1992/93) is a 16 x 18 in. generic depiction of a snowy mountain, its peak gently emerging from a rosy haze. It reminds one of Ross’s “majestic mountains” with its sloping, alpine-dotted bends and curves. Instead of foregrounding the scene in verdant grass, like Ross would, Hohn effaces the mountain’s setting in a white, pinkish abstraction. And where Ross’s details sought to emulate nature itself, Hohn deploys Richter’s palette knife technique, with its scrapes and smears redistributing the mountain snow. Though Richter has his own set of landscapes, for instance his chilly 1968–69 Corsica works, Hohn’s inclusion of Richter’s technique is more reminiscent of Richter’s Wald series from 1990 with its horizontal trails of colors. Hohn’s depiction of the wild is less the pastoral and austere romance of Richter’s scenes and more the rugged, lumbersexual succor of Ross’s. However, Hohn inscribed the pictures with allusions to the institutional stalwarts of contemporary painting to blur the distinction between Ross’s and Richter’s respective motivations. Hohn differentiates himself from these two artists by appearing lethargic in the face of beauty. This attitude can be read in his commitment to depicting subjects perceived as passé in art, such as natural landscapes.

While received art historical paradigms relegate the languid, prosaic works of Ross to kitsch, Hohn’s renderings of the Rossian landscape amplify their strange ambience, a quality closely connected to the visual culture of broadcast television. The relationship between broadcast TV, painting, and technology’s interruptive possibilities can be seen in the work of Hohn’s contemporary, the German painter Matthias Groebel, who, in his Painted Faces series made throughout the 1990s, evokes television’s ability to generate mysticism through ambient imagery. Contrasted with Groebel’s interest in the bracketing of vision through media consumption habits, the works at Greene Naftali inspire reverence toward nature, in both its sublimity and its decay. In appropriating Ross, Hohn folds into his appropriation all of the televisually mediated images of Ross: his painting practice, detailed process shots, and closely filmed images of his brush cascading across a canvas, as well as Ross’s own appearance, mode of dress, and distinctive voice. They’re campy, too, implicit with the marriage of “low” and “high” art. Hohn’s landscapes also point to the changing habits of viewing art and painting in a world marked by technologies of recreation. More than two centuries ago, Friedrich Schiller described the artist’s changing relationship to nature as a loss: “nature with us has disappeared from humanity and we encounter it again in its truth only outside this, in the inanimate world.” [2] Schiller believes that unifying with nature is now an impossibility as humans have delineated a world separate from the natural environment. The democratization of leisure time that resulted from industrialization brought with it ennui and listlessness. This retreat from nature yielded a “contemporary terror of boredom” as literary studies scholar Elizabeth S. Goodstein writes, which “is saturated with the post-Romantic resignation to a world in which neither work nor leisure can bring happiness to subjects who no longer hope for divine restitution.” [3]

In the exhibition, the “contemporary terror of boredom” comes to its most perplexing manifestation in the eight small feces-like reliefs, their brown plaster resembling sewage and excrement affixed to wooden boards yet hung with a carefulness that is facetious given their content. Hohn’s elegant presentation is a sheer veil, exposing the suppressed anxieties of the 1980s regarding HIV/AIDS by public institutions and by the straight consciousness, who submerged its fears through deliberate ignorance, changing the channel when forced to watch millions die throughout the ongoing AIDS crisis. How was this public responsible for a contemporary supposition that art must shun the Real rather than confront it? During the 1980s, the often-invoked “general population” and the United States government under the Reagan regime equated homosexuality with disease. AIDS is “the contemporary moment in a much longer history, the [...] complex interweaving of medicine and morality with surveillance and regulation [...] of sex.” [4] Psycho-social fears about anality and homosexuality thus became public policy, as 60 percent of employers by 1989 were forcing pre-employment HIV-testing on potential hires, a practice that in some places still continues today, making them urinate or draw blood to prove their lack of HIV. Lawmakers, both in the States and Germany, also proposed submitting gay people to quarantines. [5] This treatment of sexuality and disease as entwined persists today. Hohn’s panels evoke the historical desire of the dominant classes to ignore debility and disease through apparent order. Despite the evident scatological elements in this work, there is also something appealing about it, too, even chocolatey. Hohn questions our instinctive repulsion, and perhaps admires it as a particular aesthetic mode.

"Ull Hohn: No Great Mysteries," Greene Naftali, New York, 2023, installation view

Previously unseen works of enamel and varnish on display further edify his intentions. For example, the untitled splatter painting on wood from 1987 is uneasy, gesturing toward painterly tropes with its coagulated swirls of green, white, brown, and cadmium red, which orbit a white semisphere. Glazes and bulbs make these works look like pottery, disguising the wood foundation with assiduous technique. They’re notably installed on shelves rather than hung, a framing device that marks a degraded objecthood (apart from the elevated wall-mounted status of painting). Reminiscent of amateur decorative ceramics of the “paint your own pottery” trend that took off in the 1980s, they are also somehow these disagreeable objects, conjuring kitsch inflected by the finesse of Meret Oppenheim – with her uncanny adornment of objects that parody the absence of utility as a betrayal of function.

The exhibition continues the arc of earlier presentations of Hohn’s work in its foregrounding of the artist’s interest in contemporary hierarchies of aesthetics, encouraging the audience to express doubt in modern painting and culture more broadly. While prior exhibitions at Greenspon and AFA emphasized his interest in degeneracy and abjection with his fecal reliefs and umber abstractions, “No Great Mysteries” at Greene Naftali, with the addition of previously unseen ceramic-like works, is a more banal journey than previous iterations. The title gives into this mission, promising to be so unsurprising and plaintive as to exhaust any contrived attempts at profundity. But Hohn’s technical acumen elevates his subjects beyond triteness. Emergent is a dialectic of painting pursuant to a refinement of craft that simultaneously repudiates established notions of taste, resulting in an evocative blend of populist style and genteel sensibility.

“Ull Hohn: No Great Mysteries,” Greene Naftali, New York, March 24–April 29, 2023.

Joel Danilewitz works for the Brooklyn Rail. He lives in New York.

Image credit: Courtesy of the Estate of Ull Hohn and Galerie Neu, Berlin; photos: Zeshan Ahmed/Greene Naftali, New York

Notes

| [1] | “Ull Hohn: No Great Mysteries,” exh. press release, Greene Naftali, www.greenenaftaligallery.com/exhibitions/ull-hohn-no-great-mysteries. |

| [2] | Friedrich Schiller, “On Naïve and Sentimental Poetry,” in Essays, ed. Walter Hinderer, trans. Daniel O. Dahlstrom (Continuum, New York, 1998), 204–7. |

| [3] | Elizabeth S. Goodstein, Experience without Qualities: Boredom and Modernity (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press), 2008. |

| [4] | Frank Mort, “Introduction,” in Dangerous Sexualities: Medico-Moral Politics in England since 1830 (London: Routledge, 2000), 2. |

| [5] | Mark Kaplan, “AIDS and the Psycho-Social Disciplines: The Social Control of ‘Dangerous’ Behavior,” in “Challenging the Therapeutic State: Critical Perspectives on Psychiatry and the Mental Health System,” special issue, The Journal of Mind and Behavior 11, no. 3/4 (Summer and Autumn, 1990): 337–351, at 343. |