FRAGMENTS, FIELDS, AND BODIES: FORMATIONS OF SELFHOOD THROUGH TRANS DEPICTION By J Jan Groeneboer

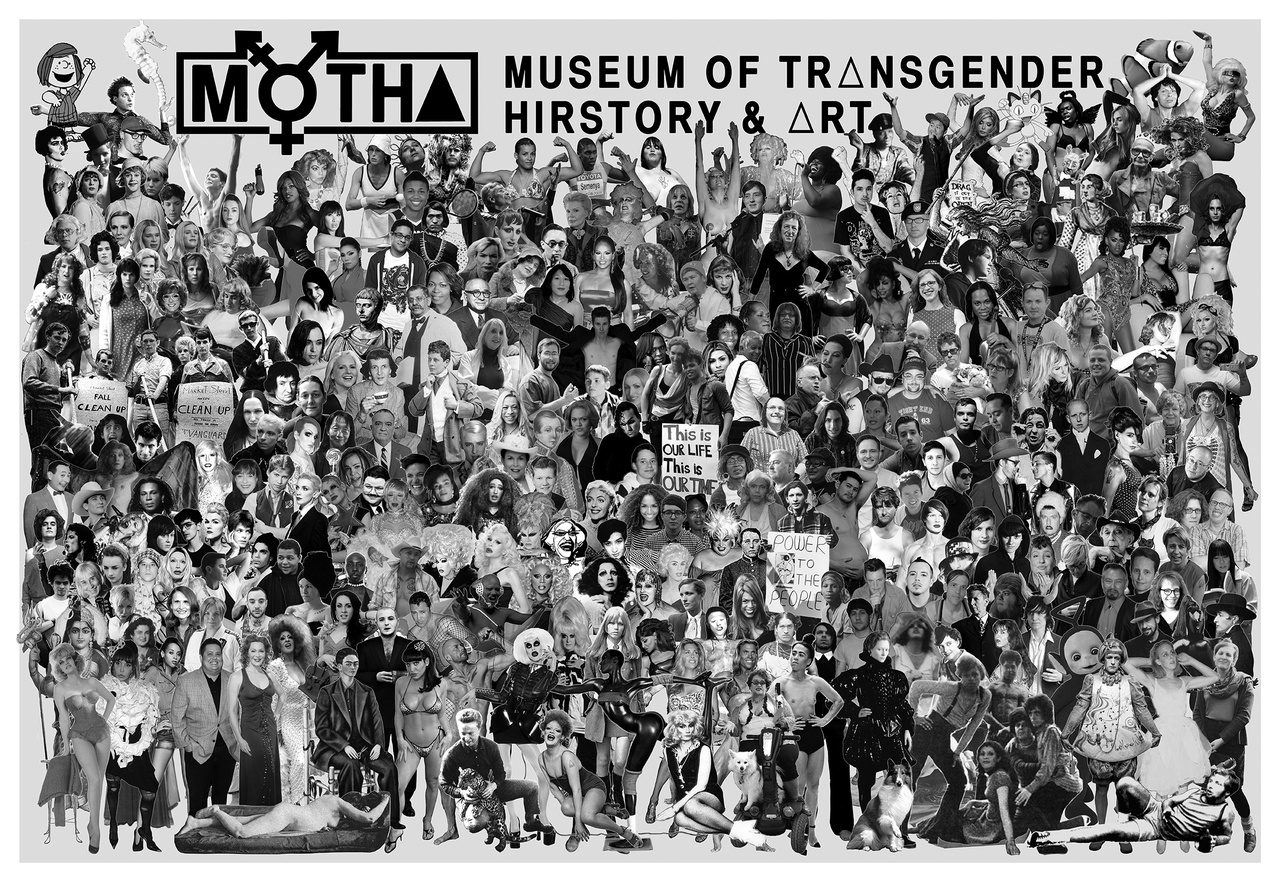

Chris E. Vargas / MOTHA, “Transgender Hiroes,” 2013, promotional broadside

In the late nineties, during a time where few representations of trans men were widely available, my awareness of my transmasculinity emerged. The internet was young then, and people didn’t publicly document their transitions on social media because those platforms did not exist yet. What was available to me then was both a reflection of that time and the particulars of what I had access to. I came out in a community which was made up of queer women, drag kings, gender queers, a few gay men, and a handful of trans people. Beyond snapshots of my friends and the performances and artworks we made, my exposure to depictions of trans men were extremely limited. Before I encountered images of trans men, I saw images of trans women and lesbians and gay men. These constellations of depictions shaped my early understanding of myself as transmasculine. Even fragments that are not directly representative can compose a sense of selfhood.

Among these early fragments were photographs by Nan Goldin and Brassaï. Goldin’s images of intimacy across difference were particularly affecting, and I would pour over her photobook The Other Side. [1] Her pictures of community and relationships resembled something akin to what I knew through my own community. In her images, her love for her friends (a community of trans women and drag queens) is clear and tender. I found affinity and inspiration in her images of trans women living in close friendship. Seeing them was deeply healing, having grown up with a largely destructive cinematic repertoire of trans representation. Even through Brassaï’s voyeuristic observational perspective, I found solace in his photographs of gays and lesbians in Paris in the thirties. The first time I viewed Un couple au bal Magic-City (1931–33), [2] I had an extraordinarily visceral response. In the image, a femme person dances with a suited man. Dressed in all white, she wears a magnificent floppy wide-brimmed hat with rouching at the underside of the band and a large flower-like orb of the same material attached at the crown, which she has paired with an eyelet cotton dress, a long draping beaded necklace, and opera gloves. She stares directly at the camera and smiles out at the viewer. When I encountered this image, I felt a full force of awareness that was at first more phenomenological than cognitive. All the cells in my body simultaneously exalted. I saw her blissful expression and understood that trans people have always existed and that this joy was possible for me too.

Outside of my immediate community, I hadn’t seen many representations of trans men until I encountered Loren Rex Cameron’s Distortions [3] series in 1998. My roommate, who was also trans, photocopied and wheat-pasted this series on the carmine wall above his bed. Distortions consists of three black-and-white photographic self-portraits framed in bold text with phrases presumably said to Cameron in response to his transmasculinity. Each work focuses on a different theme of his experience: In the first, the phrases appear to be from cis people grappling with Cameron’s transition (Are you misogynist? I just can’t get used to calling you “he.” Maybe you are just homophobic), which surround an image of Cameron, hunched over, brow furrowed, looking down outside of the frame of the photo. In the second image, he looks alluringly out at the viewer and the text focuses on desire and fetishism (You’re so exotic. My attraction to you doesn’t mean I’m gay: you’re really a woman). The text in the third piece suggests dislocation within binary spaces, both physical and in terms of attraction (This is a womyn-only space. Sorry, but I don’t like men. I can’t be with you, I’m not a lesbian. You piss like a woman. You don’t belong here), framing Cameron as he wears an exasperated expression and holds a frustrated hand to his face. Each sentence is structured as a direct address enforcing the expectation that Cameron alone must account for the speakers’ transphobia and reconcile their contradictions.

Shortly after, I got a copy of Cameron’s monograph Body Alchemy [4] – the book my roommate had made his Distortions photocopies from. It includes several photographic series: God’s Will – Cameron’s most well-known self-portraits – features him in quintessential body-builder poses holding a scalpel, lifting a dumbbell, and injecting testosterone. Our Bodies details different types of surgeries through photographs and first-person narratives. In The New Man Series, Fellas, and Emergence, Cameron photographs other trans men and pairs them with sincere and straightforward first-person texts. Each varying experience of transitioning is chronicled with emotive detail. There are direct accounts of the effects of testosterone and surgeries, of coming into a holistic relation with oneself, and of traversing shifted gender relations. Black, Indigenous, and white trans men are represented throughout. There is a religiously devout electrician, a fitness trainer, and a factory worker with kids and a long-distance girlfriend, among others.

Within these accounts are stories of love and dating through transition: trans men relay their journeys dating women, some are straight, others mourn losing lesbian community. There are trans men who cruise in gay men’s spaces (this is five years after Lou Sullivan passed away and twenty-three years before a selection of his diaries, We Both Laughed in Pleasure [5] , was published) and a T4T relationship. This book constituted abundance in a sparse field of representation, and I understood my own transmasculinity in relation to its narratives. However, this relation was ambivalent. I was grateful for images that reflected who I am and for their guidance (I did not yet know how hormones would affect me or how my own transmasculinity would develop and change over the years). And the cause of my deepest ambivalence: Some perspectives in the book were based in essentialist logic, and I found them suspect.

In his Self-Portraits series, Cameron photographs himself smashing a bottle against a fence accompanied by the text “Testosterone,” in which Cameron describes his struggle with his inflated temper, which he attributes to his hormonal injections: he recounts an instance where he punches a man in the face for verbally assaulting a woman. When I first encountered this text, Cameron’s suggestion that testosterone was responsible for his violent aggression grated against my understanding of power and socialization and what I knew of most of the men in my life. I imagined that he might be a person whose anger was already present, but through transition, the boundaries of allowable gendered behavior shifted from repression of anger to accepted expression, and he felt more comfortable acting on his temper physically. If the hormone testosterone is the root of toxic masculinity, then we are trapped in an essentialist logic where biology is the cause of behaviors instead of power and its resulting social conditions (and this has implications for race and disability as well as gender). When I went on hormones, I decided that I would be acutely aware of how testosterone affected me. I wanted to consciously incorporate my masculinity into the framework of biological and social relation that my non-essentialist and feminist upbringing had given me the critical tools to understand.

In Body Alchemy’s representations of trans men, I could see aspects of myself reflected, and I also saw difference. When there are so few representations, an enormous amount of pressure, expectation, and scrutiny are placed on the few that exist. As I revisit the “Testosterone” text 25 years later (from the vantage point of relatively ample trans representation), I also see an earnest singular account of the struggle to understand the anger Cameron was experiencing at that point in his transition. Loren Rex Cameron died on November 18, 2022, and a few months later, the New York Times published an obituary with the subheading: “Mr. Cameron’s groundbreaking portraits of himself and others, collected in his book, ‘Body Alchemy,’ inspired a generation of transgender people.” Body Alchemy provided a critical foundational dialogue that I could understand myself in relation to. Even representations to define oneself against can be a formative gift.

I sometimes wonder if, as an artist, my mode of working in abstraction to address the politics of representation is rooted in these early experiences of representational lack. I want to make palpable a felt sense of transness without using representational figuration, because this is a foundational aspect of my experience. And while this is true, I’ve simultaneously searched out depiction and understood how crucial it is to see oneself in relation to a field of representation.

In 2013, as part of the Museum of Transgender Hirstory & Art (MOTHA), Chris E. Vargas created the Transgender Hiroes [6] broadside, a poster that depicts over 280 transgender figures. Vargas cut photos and drawings of trans-related figures from their original context and collaged them together to a create a crowd of transgender representation. Historic figures are placed beside renowned contemporary activists and artists, revealing the temporal possibilities of trans community. Vargas situates fictional depictions in uncomfortable proximity: celebrated fictional characters such as Orlando share space with those from Hollywood movies such as Sorority Boys, White Chicks, Mrs. Doubtfire, and Psycho. Both Brandon Teena and Hilary Swank depicting Brandon Teena in Boys Don’t Cry are included. In Transgender Hiroes, the revered and harmful comprise a porous field of trans consciousness. The MOTHA website featuring the broadside suggests, “Buy one and collage yourself into the mix today!,” inviting viewers to see themselves as part of this field. Considering the scope of all that is included, that relation is both affirming and fraught.

Seven years later, Sam Feder’s documentary Disclosure examined many of the same offensive cinematic characters included in Vargas’s Transgender Hiroes. In Disclosure, numerous trans people address these filmic portrayals, infusing feedback into the original representations. Vargas’s inclusion of these characters also makes them addressable within the constraints of the medium of collage. In Transgender Hiroes, the form of address is ambivalent; the individual figure represents a fragment of a whole, but its identifications are not cohesive. This pliability in what constitutes an entire body of trans community reveals Transgender Hiroes’s critical position in transgender representation, and its invitation to “collage yourself into the mix” asserts the position that no image can be wholly representative or total.

The entire field of trans representation that I encountered impacted my understanding of myself. Representations can be just as constitutive as experience in the formation of selfhood, because their degree of presence and the nature of the depictions are experience. It is strange now to be in a period where I can see portrayals of other trans men without much effort. I can open an app or a browser and see pictures of trans people within seconds. Sometimes the algorithms deliver these images directly to my feed without prompting. It is also strange to concurrently be in an era where a record number of anti-trans bills have been proposed – simultaneously an extreme backlash against this visibility and a strategic use of trans representation in the contemporary rise of fascism. I wonder how this uneasy relation will impact ongoing formations of selfhood, both individually and generationally, and what this means for the way representation rests in and arrests our bodies.

J Jan Groeneboer is a transgender artist, writer, and educator. In his visual practice, he works in abstraction to address the politics of representation. He developed this strategy to examine the expectation that transgendered people be readily available for visual scrutiny. Most recently, the 2016 essay “Seeing Commitments: Jonah Groeneboer’s Ethics of Discernment” was in included in the “Opacities” section of David Getsy and Che Gosset’s “A Syllabus on Transgender and Nonbinary Methods for Art and Art History” (Art Journal, Winter 2021). As a writer, Groeneboer has participated in numerous panels and in symposiums and is a contributing critic for Artforum.com. His essay “Erasure through Representation in Boys Don’t Cry” is included in the forthcoming issue of the Journal of Gender and Sexuality.

Image credit: Courtesy of Chris E. Vargas

Notes

| [1] | Nan Goldin and David Armstrong, Nan Goldin – The Other Side (New York: Scalo, 1993). |

| [2] | Brassaï and Roger Grenier, Brassaï (London: Thames and Hudson, 1989). |

| [3] | Loren Cameron, Body Alchemy: Transsexual Portraits (Pittsburgh, PA: Cleis, 1996), 28–32. |

| [4] | Loren Cameron, Body Alchemy. |

| [5] | Lou Sullivan, We Both Laughed in Pleasure: The Selected Diaries of Lou Sullivan, 1961–1991, ed. Ellis Martin and Zach Ozma, introduction by Susan Stryker (New York, NY: Nightboat Books, 2019). |

| [6] | “Transgender Hiroes,” MOTHA (website), accessed May 12, 2023. |