DO YOU REMEMBER CULTURE WAR? John Beeson on “Deserting from the Culture Wars,” edited by Maria Hlavajova and Sven Lütticken

“Tony Cokes: To Live as Equals,” BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht, 2020, installation view

Historians agree: The US culture wars of the 1980s and ’90s were contentious and sprawling. Less clear is how individual skirmishes interrelated. Stretching more than a decade and into the early 2000s, across the pages of newspapers and onto the floor of the Senate, the culture wars were as protracted as they were volatile. In the absence of agreement as to what united disparate struggles, there has nevertheless long been consensus that they had lasting effects. As concerns contemporary art, Carole S. Vance noted in her 1989 essay “The War on Culture” [1] how, time and again, funding bodies withdrew or withheld taxpayer dollars. Art, often involving religious iconography or dealing with sexuality, gender, and race amid the AIDS crisis, functioned as a pretext for both moralization and privatization. Conservatives rallied around claims of obscenity and a call to defund the National Endowment for the Arts. In 1999, Michele Wallace, in “The Culture War Within the Culture Wars: Race,” [2] pointed out what Vance neglected. Artists of color, she argued, were not affected by controversy, censure, or loss of public funding in the same way as white artists; their exclusion from the market and from institutions was continuous. Whether we emphasize economics or identity – or whether we focus on the imbrication of the two – impacts our understanding of the culture wars, then as now.

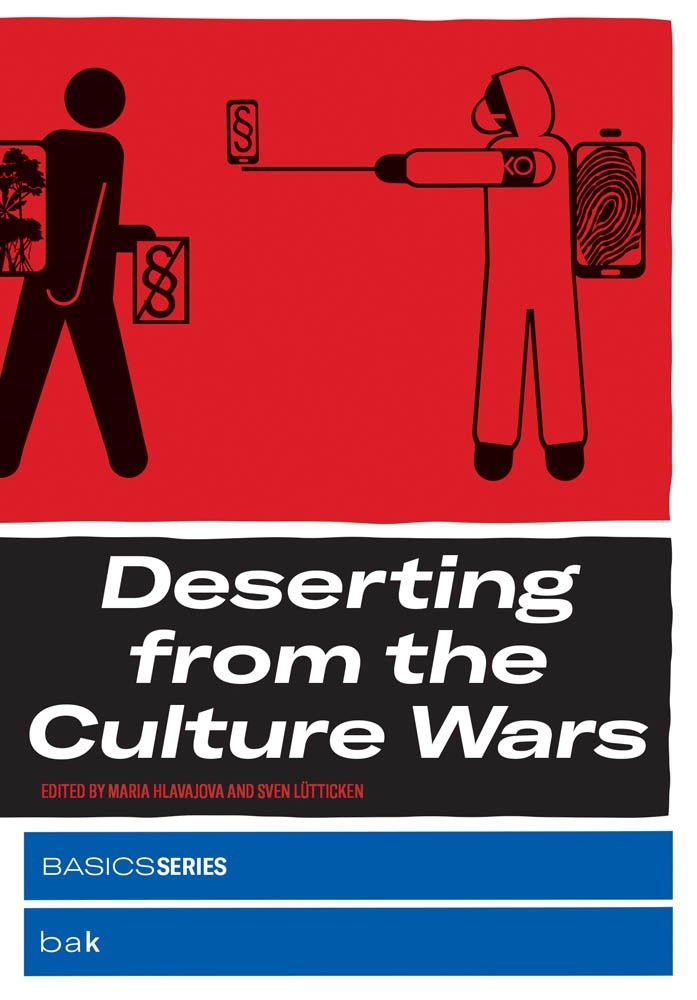

Analyses of the culture wars have proliferated in recent years. A new essay collection offers an opportunity to step back and evaluate that discourse. Deserting from the Culture Wars derives from the ongoing research series Propositions for Non-Fascist Living, begun at BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, in Utrecht in 2017. “The culture wars,” writes Maria Hlavajova, BAK’s director and one of the book’s co-editors, “seem administered as an anesthetic that disorients, bewilders, and consequently exhausts.” [3] While the essays differ in focus and approach, along the way, a portrait of the culture wars emerges. Hlavajova, Tom Holert, and Sven Lütticken each portray the terms of contemporary struggles as an invention of the Right, a determination that underpins their anti-culture-war stance. Contributors oppose burgeoning fascisms in the UK, Norway, Brazil, and elsewhere. They push for new solidarities to counter the rifts opened up under neoliberalism, proposing cooperation instead of competition and democratic ownership in lieu of private property.

It is significant that the collection takes culture wars to be the order of the day, coming as it does from a European perspective. In accepting culture-war cultural politics as predominant, and US culture wars of the ’80s and ’90s as part of a shared history, the book represents a welcome antidote to the narrative of exceptionalism latent in descriptions of the culture wars as a US-specific phenomenon. Deserting from the Culture Wars is part of a sizable literature, dating back decades, that refers to debates occurring internationally as culture wars. The book provides further evidence of the need for struggles to be thought alongside globalization, potentially as a local correlate. Bini Adamczak writes of a “return of European fascism far beyond Europe.” [4] In our contemporary political landscape, alliances are said to solidify among identity groups, in polarized political factions, and within nations. Authors discuss contemporary nationalisms in the context of immigration, but their emphasis tends to fall on income and wealth inequality. The collection’s authors envision the spread of leftist politics beyond national borders based on economic solidarity. Art would promote this process through its affective dimension as well as its capacities for fostering collectivity and truth-telling.

The thinking in Deserting from the Culture Wars is informed at multiple points by French and Italian autonomist political theory, and the degree to which autonomism anticipated culture-war cultural politics is telling. It is one of several bodies of thought since the 1970s that conceives politics in terms of allegiances that are formed, rather than given. In the wake of the radical movements of the ’60s, autonomists theorized a shift in politics away from the party, toward social relations. According to Félix Guattari, as capitalism rendered old alliances obsolete and expanded into ever more aspects of life, it drew both a “micro-politics of fascism” and coincident lines of resistance in its wake. Through a constant search for new alliances (“transversal” relations), we might stifle these micro-fascisms while making political gains. If autonomism emerged out of a series of wildcat strikes – and posited that “Only when the worker’s labor is reduced to the minimum is it possible to go beyond, in the literal sense, the capitalist mode of production” – then desertion here appears to be a refusal of culture-war cultural politics, which are, by implication, capitalist in nature. [5]

Deserting from the Culture Wars indicates that the definition of the culture wars remains contested, and that how they are invoked is meaningful. The collection prompts us to imagine a post–culture war future following desertion, from which point we could look back over a past paradigm. The book invites both historical and epistemological reflection. When and where did the culture wars begin and end? What stood behind them, and what was the extent of their influence? In prompting such questions, the essays are symptomatic of recent discourse, as much as they are a productive intervention into resurgent debates. Somewhat infamously, in A War for the Soul of America (2015), Andrew Hartman argued that culture wars were a thing of the past. When a second edition of the book appeared in 2019, it was accompanied by a new conclusion in which Hartman noted their return. But did we ever really leave the culture wars behind, even temporarily?

“Kader Attia: Fragments of Repair,” BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht, 2021, installation view

Given the genealogical tack of most recent analyses, writers contemplate how contemporary debates emerged out of, while also deviate from, earlier struggles. Frequently, the meaning of the culture wars is sought in a point of origin, whether traced back to the moment when the term became common usage or, more often, pinned to the book that popularized it. James Davison Hunter’s definition from 1991 has become cliché: “a struggle over national identity – over the meaning of America.” [6] Such language underlies the received idea that culture wars are US-specific. Joe Biden maintains this rhetoric, emphasizing its eschatological dimension through an appeal to “restore the soul of America” voiced twice in his victory speech this past November and again in his inaugural address. Whereas Hunter’s Culture Wars: The Struggle to Define America serves as a faithful meridian for the wars’ essence, the prevailing account of their historical emergence frames them as a counterrevolutionary response to ’60s social movements. From this perspective, the culture wars amount to a conservative backlash against progressive social gains, including civil rights, as well as the economic redistribution they entailed. But the claim is heard just as often, coming from the Right, that it was the Left who unduly politicized social issues and cultural production. Turning this stalemate around, we might put it to some use. What if instead of tracing the culture wars backward, we plumbed thinking about them? Shifting our attention from origins and ends to preconditions, we could ask what underwrites the culture wars, what unites them across time, and what sets them apart.

Such an archaeological approach would entail acknowledging that how one conceives of the culture wars itself carries meaning. A case in point is Deserting from the Culture Wars’s proposition to desert, which has stakes that go unaccounted for in the book. The stance relies on the assumption that the culture wars are a project of the Right. It implies that cultural issues distract from matters of economics, which are both the root of contemporary conflicts and a potential solution, through transnational solidarity. In fact, anti-culture warriors can be found on the Left and the Right, and insinuations that the culture wars are a diversion have long functioned to obscure the real-world stakes of cultural politics. [7] Deserting from the Culture Wars’s anti-culture-war stance thus raises questions about the politics the book signals as well as the alliances being sought. At the same time, its discussion of art’s position within contemporary cultural politics is much needed. Art has an important role to play in developing an archaeology of the culture wars. Artists’ historical siting of their work in relation to discourses such as culture war debates, and insistence on the determining effects of non-aesthetic discourses, means that artworks are invested with insights into the operations of those debates. Besides the best-known cases (Serrano, Mapplethorpe, Ofili), art is also one of the fields of struggle least understood within prevailing analyses. Following Michele Wallace, the impact of the culture wars would differ depending on an artist’s subject position. Judging from recent discourse, there is an ever-present danger when it comes to the culture wars: of viewing them through too narrow a focus and either omitting their entanglements, neglecting their foundations, or driving toward bad-faith alliances. Deserting from the Culture Wars confirms the need to better understand what we would be deserting as well as the implications of any attempt to decamp.

Maria Hlavajova and Sven Lütticken (eds.), Deserting from the Culture Wars, Cambridge: MIT Press, 2020, 150 pages.

John Beeson’s writing has appeared in Artforum, frieze, BOMB, May, and elsewhere. He is pursuing a PhD in art history at Columbia University.

Image credit: 1. & 3. Photo: Tom Janssen

Notes

| [1] | Carole S. Vance, “The War on Culture,” in Art Matters: How the Culture Wars Changed America, eds. Brian Wallace, Marianne Weems, and Philip Yenawine (New York: NYU Press, 1999), 221–231. Originally published in Art in America 47 (September 1989), 39–43. |

| [2] | Michelle Wallace, “The Culture War within the Culture Wars: Race,” in Art Matters, 166–181. |

| [3] | Maria Hlavajova, “Foreword,” in Deserting from the Culture Wars, 13. |

| [4] | Bini Adamczak, “The Promises of the Present,” in Deserting from the Culture Wars, 96. |

| [5] | Sylvère Lotringer and Christian Marazzi, “The Return of Politics,” in Autonomia: Post-Political Politics, eds. Sylvère Lotringer and Christian Marazzi (New York: Semiotext(e), 2007), 16. |

| [6] | James Davison Hunter, Culture Wars: The Struggle to Define America (New York: Basic Books, 1991), 50 (emphasis in original). |

| [7] | The editors of American Affairs spoke as right-wing anti-culture warriors when they argued, in a debate from May 26, 2017, that the culture wars were over – thus bracketing out all but class in terms of identity as part of their bid to leftists to abandon cultural issues, broker an agreement on economics, and join a newly nascent nationalism. |