OH BONDAGE UP YOURS! Steven Warwick on Ilya Lipkin at Galerie Lars Friedrich, Berlin

“Ilya Lipkin: Eau d'Offense,” Galerie Lars Friedrich, Berlin, 2021, installation view

The rituals of sadomasochism being more and more practiced, the art that is more and more devoted to rendering its themes, are perhaps only a logical extension of an affluent society’s tendency to turn every part of people’s lives into a taste, a choice. [...] But once sex becomes defined as a taste, it is perhaps already on its way to becoming a self-conscious form of theater, which is what sadomasochism – a form of gratification that is both violent and indirect, very mental – is all about. – Susan Sontag [1]

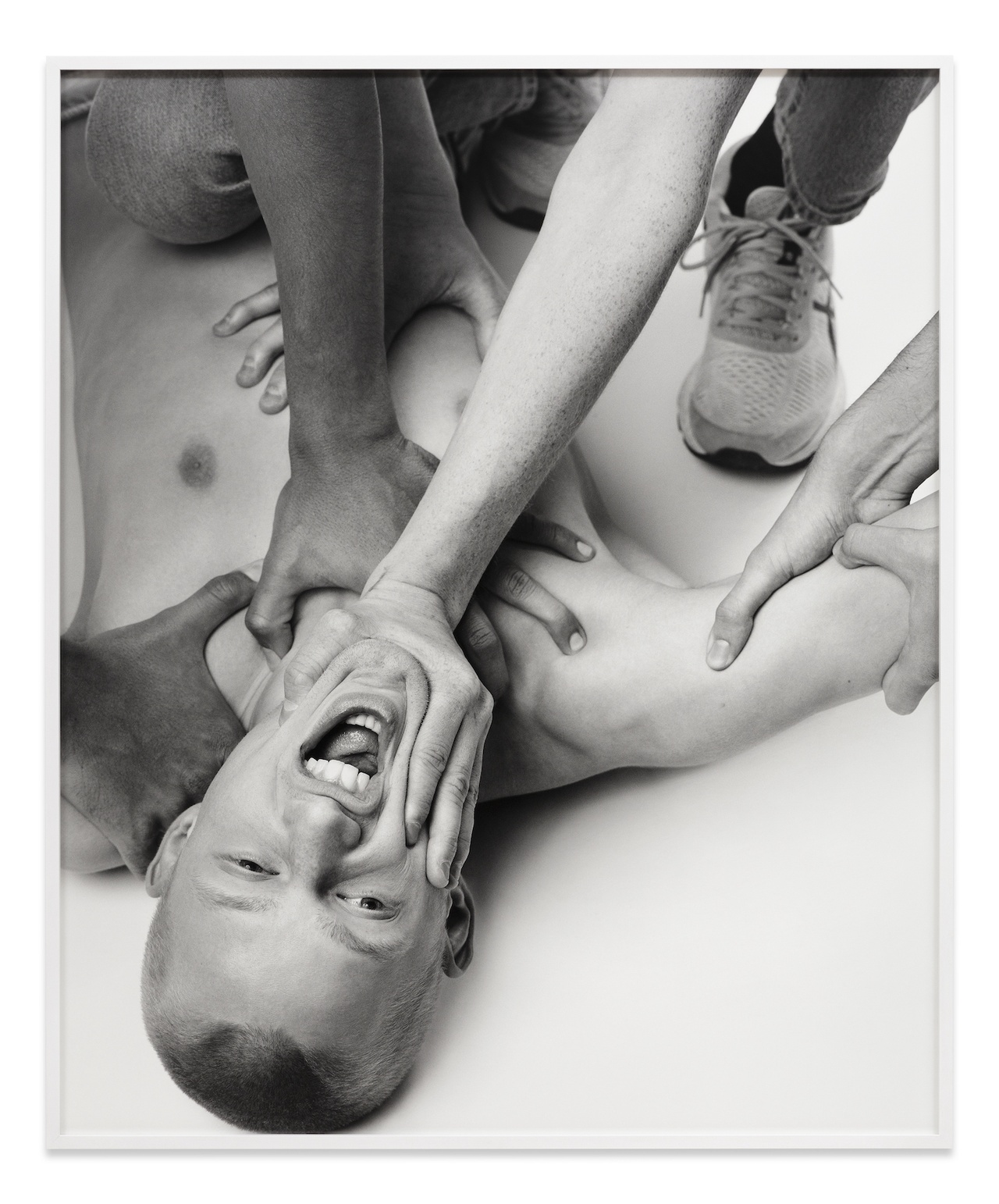

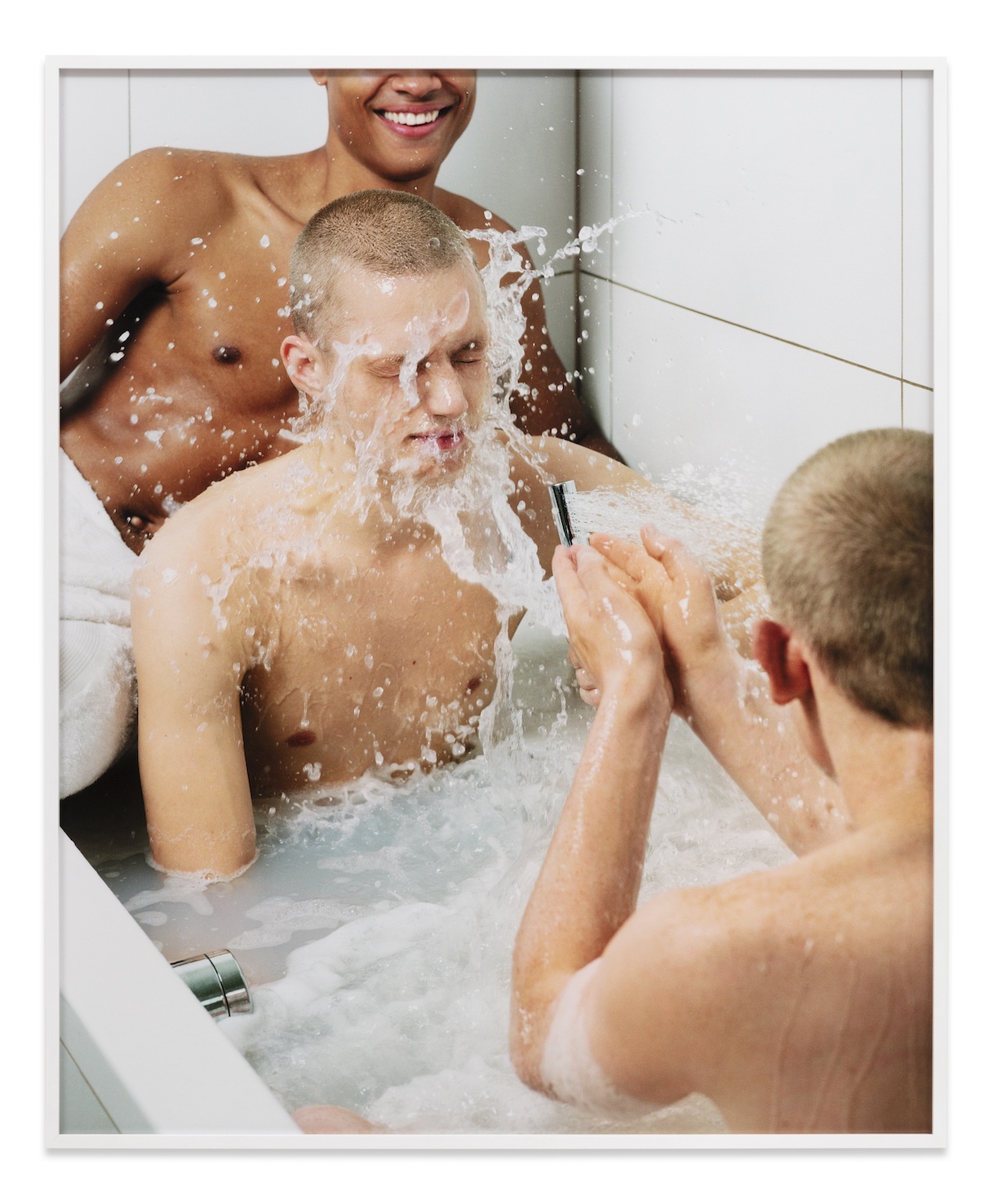

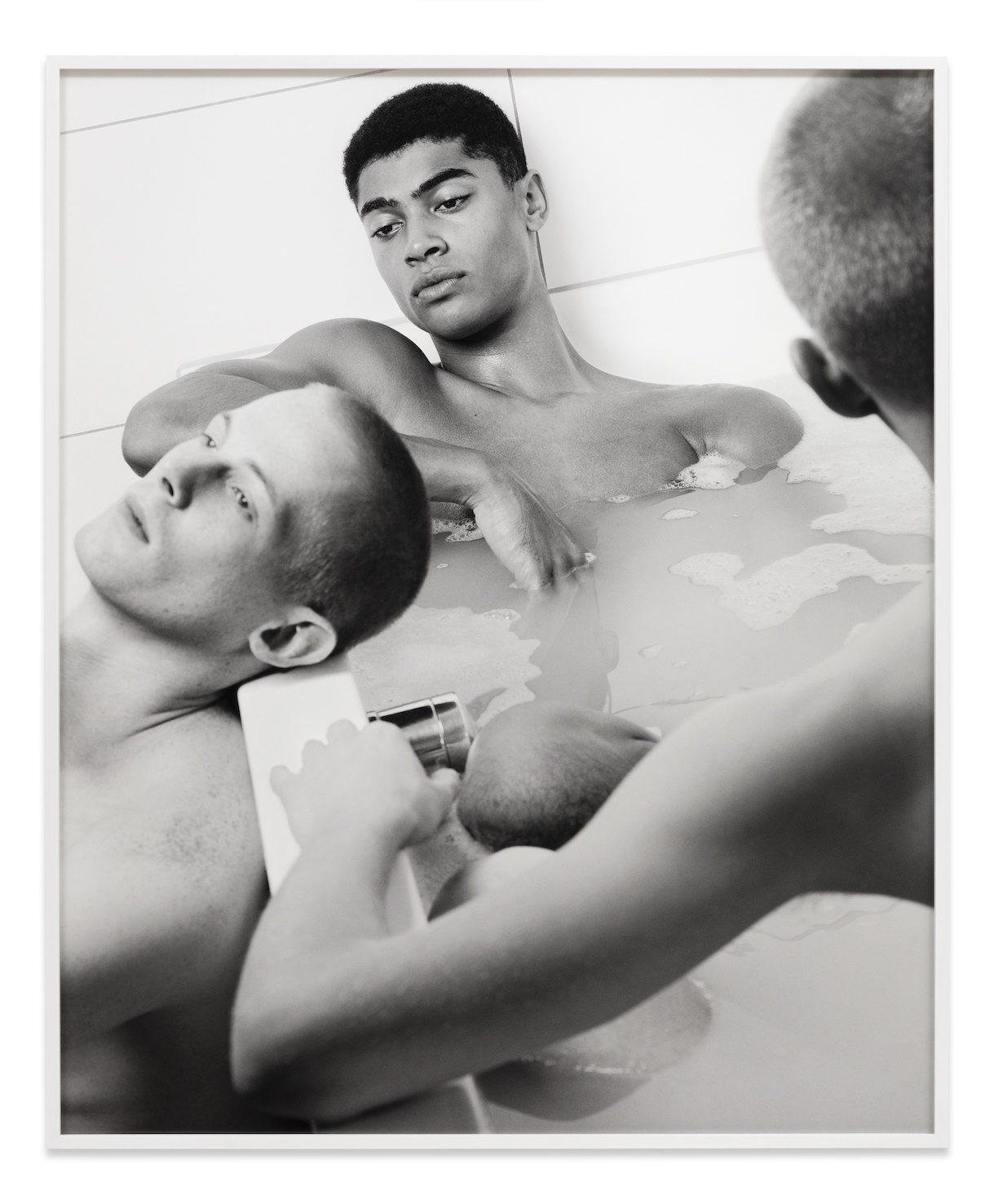

Writing about the fetishized body ideal in the work of Leni Riefenstahl, Susan Sontag reflected on what it is that attracts us to images of fascism: Why are they so seductive? How does the idealized body play into political ideology? The answer lies in the fact that such images are created with this intention. This logic also pervades modern advertising, binding the viewer to interact with and desire an object. People are treated like objects, in competition with each other on- and offline where distance enables a detachment through which anyone can project their unconscious drives onto the subject as an object. Ilya Lipkin engaged some of these questions in his latest exhibition, which consisted of six untitled medium-format photographs – black-and-white and color – of young, stereotypically handsome, thin, skinhead male models engaging in various stages of male bonding: horsing around, splashing each other in the bath, wrestling and writhing about, like school children during a lunch break. Such rituals have been highly scrutinized in recent years as ever decreasing social spaces become further politicized and sites of respite become increasingly sought out. [2]

Ilya Lipkin, “Untitled,” 2021

Upon first glance, I am reminded of sites of male aggression where hierarchical masculinity is acted out in spaces such as communal showers and locker rooms in prisons, the military, or sports recreation centers. One thinks of cinematic examples such as Full Metal Jacket (1987), Scum (1979), or The Firm (1989), all of which are pointed critiques of such violent behavior and dominance. In The Firm, Alan Clarke confronts the issue of football hooliganism and male aggression (and white nationalism – the ultimate identity politics?) where a man, played by Gary Oldham, is losing control of his bland, quotidian life and seeks to enliven it with the adrenaline rush of the football match. Lipkin’s photographs, in contrast, are more “metrosexual,” lacking the camp butchness of, say, Bruce Weber’s advertising photography from the 1990s, or the rugged Marlboro Man. Instead, Lipkin’s models look more like adolescents trying to fulfill the transition into normative manhood, their attempts only moving them further away from their goal.

Lipkin’s show is more about photography itself than mere social commentary, however. There is a methodology here that focuses on an absence of seduction, similar to Robbe-Grillet’s “chosist” experiments in the Nouveau Roman or Christopher Williams’s photos of the camera. With a clinical detachedness, the subjects are decidedly unseductive, which jars the gaze trained on corporate advertising, a genre in which Lipkin also works. Lipkin consciously portrays the models with a lack of markers of consumer identity – hence the naked body, clothed only in a generic white towel, hidden by bath water, or cut out of the frame – leaving the viewer with few identifiers of social standing, which reminds us and heightens how we read each other – online, at openings, in interviews. In light of this absence, two details become more glaringly apparent to the viewer: a grubby sports sneaker that wouldn’t look out of place in a Tillmans photo or an Anne Imhof performance, and a detailed close-up of a man shaving with a branded razor.

Here, Lipkin ironically evokes Gillette, with its slogan “The best a man can get,” as one stares at the image (Untitled, 2021), drawing attention to the corporate language of advertising. This language also pervades our imaginary as we endlessly scroll and consume images of who we want to be today. The art world’s flirtation with fashion and its imagery, exemplified best by collaborations with its favorite bad-boy brand, Balenciaga, can be detected here, and Lipkin has indeed shot a Balenciaga campaign. He plays with the tropes of commercial photography to explore how the individual is captured, identified as a demographic in a market, and sold back to the consumer. In calling the exhibition “Eau d’Offense,” Lipkin wryly evokes the branding of perfumes, applied to the subject, to make them more desirable. The title refers more specifically to a quotation from a German soldier in the First World War, Ernst Jünger, in his war memoir In Stahlgewittern (Storm of Steel, 1920), in which he describes how one could smell the offensive of war among reeking smells of dead flesh and ammunition.

Ilya Lipkin, “Untitled,” 2021

Jean Cocteau once said that every glance in the mirror tells us death is at work. The clinical shot, with the extreme close-up of freshly shaved hair on a cheek, recalls Patrick Bateman’s monologues in American Psycho, in which he tirelessly lists products that he uses in between his murderous sprees. After one self-care session he utters, referring to himself, “Feel like shit, but look great.” Looking at Lipkin’s photograph, the viewer stands where the mirror the shaving subject looks into should be; we become the mirror, voyeuristically staring back into the vulnerable gaze of the shaving man while he performs his role. The excessive detail of the hairs already cut from shaving as the razor glides down the face is, admittedly, seductive and, for a second, draws us in. But Lipkin sets up the shot so that the man’s vulnerability is more wistful or melancholic than that of the Marlboro man of yore. He is more a man-child, still not in the promised land, nervously looking over his shoulder, in part out of a narcissistic need of approval from others but also in fear of being removed from circulation in the sadomasochistic gaze of subjects consuming each other in the social sphere.

In three untitled images of men play-fighting – being held down, subjugated, put in a headlock or being splashed with bath water – the image reads as decidedly not macho. The photos have nothing to do with homoeroticism or sexuality, instead appearing pointedly silly. They neither seduce nor read as “serious”; rather, they capture a tender moment of play and goofiness. Any hint of sadomasochistic dominance has collapsed to read more as a heterosexual camp or ironic sensibility. [3] A wistful scene of men lying together inside and against the bath is not convincing as a sincere image of male bonding. Again, on closer inspection, this is a deliberate decision, for like the position of the viewer as a shaving mirror, here the viewer is crouched among the young men, sitting on the bathtub rim, implicated as part of the group instead of a passive voyeur.

Ilya Lipkin, “Untitled,” 2021

While the images display models who would promptly be categorized as “Millennials” by the media, the cool detachment and sensibility in Lipkin’s work is closer to strategies in photography from around the turn of the millennium. Formally, the works evoke artists who play with fashion photography tropes in order to smash the image with something that detracts from the seduction, including Sabine Reitmaier, Josephine Pryde, Bernadette Corporation, and, more curiously, Suzanne Opton, namely her Soldier series (2006) of portraits of soldiers returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. In the latter, the soldiers look dejected or stare into space, their passive expressions framed in a headlock or their heads leaning against a flat surface in a similar manner to how Lipkin frames his fighting scenes.

As per Wendy Brown, instead of focusing on states of injury, Lipkin’s cool inquiry into the unfairer sex brings the rhetorical beast of “manhood” center stage and, through the conventions of photography, presents a soft subversion of current taxonomies and arguments, of intellect over feeling. Similar to Philip Guston’s self as KKK cartoons (1969) or Kippenberger’s Ich kann beim besten Willen kein Hakenkreuz entdecken (1984), Lipkin reflects on masculinity, and how it is constructed through media, to parse how we construct interpersonal relations with a financial incentive and treat each other as consumer objects. Corporatist rhetoric or empty self-preserving slogans (think of “Nazis raus” (Nazis out); wohin denn? (but where to?) Not In My Back Yard!) mirror the emptiness of branded signifiers and in turn the loneliness of the contemporary condition in Western societies.

“Ilya Lipkin: Eau d’Offense,” Galerie Lars Friedrich, Berlin, March 19–April 24, 2021.

Steven Warwick is an artist, writer, and musician based in Berlin. He released the album MOI on PAN shortly before the lockdown.

Image credit: courtesy of the artist & Galerie Lars Friedrich, Berlin. Copyright Timo Ohler.

Notes

| [1] | Susan Sontag “Fascinating Fascism,” New York Review of Books, February 6, 1975. |

| [2] | I personally have been skeptical of “safe spaces” after the Pulse nightclub shooting in 2016 in Florida, and while understanding the collective need for subjectivity to be protected and preserved, the rhetoric of the culture wars is often a red herring to obfuscate deeper structural problems of inequality and disparity. |

| [3] | Which brings to mind Lipkin’s previous shoots of a woman glassy eyed with tears wearing a Soviet sickle earring (Untitled, 2020, shown at Perrotin Gallery), or his fashion shoot for the Dazed & Confused April 2020 issue with stylist Claudia Sinclair, with its of model Veronika Kunz looking into the mirror reading Christopher Lasch’s The Culture of Narcissism. |