REGARDING THE PAIN OF AI REPRODUCTION (OR NO ALGORITHM WILL RESTORE YOU) Luzie Meyer on Loretta Fahrenholz at Fluentum, Berlin

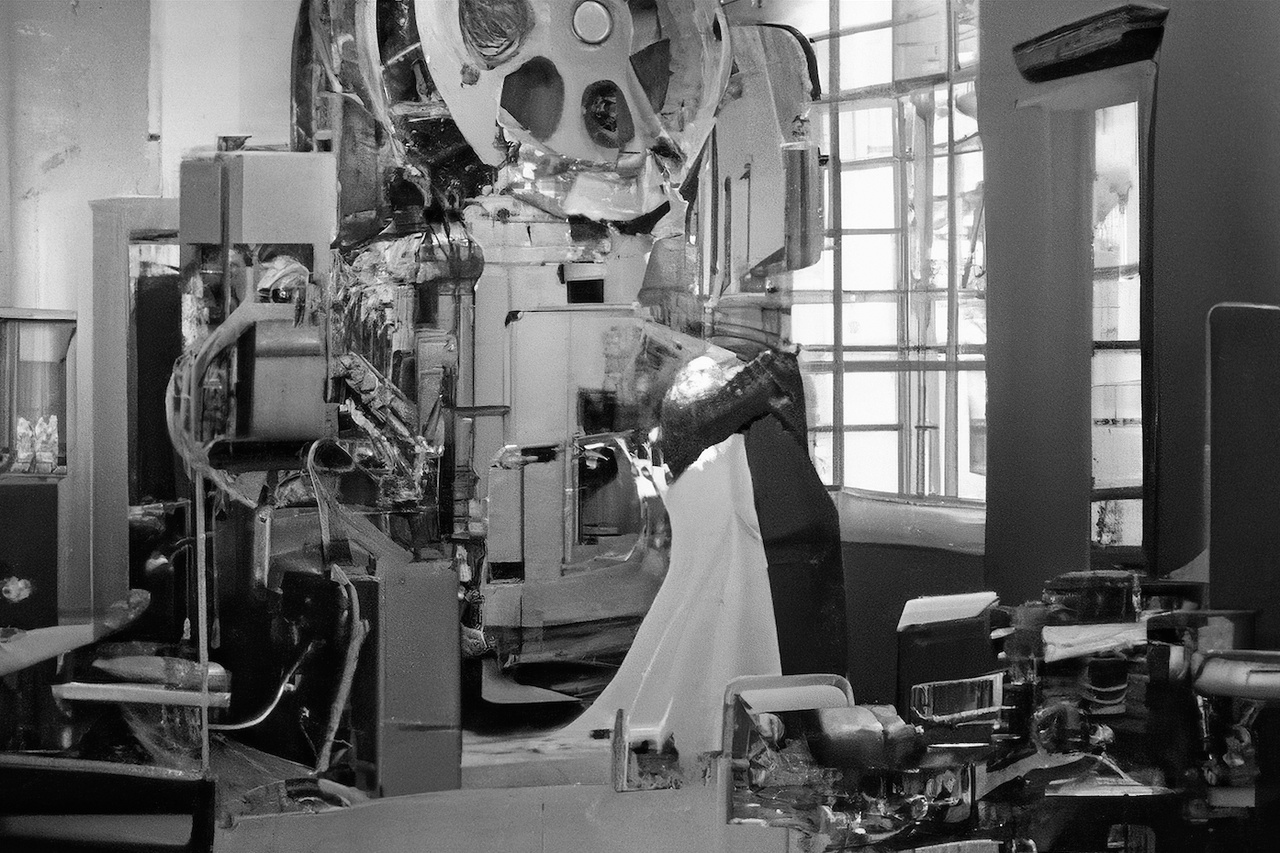

“Loretta Fahrenholz: Trash The Musical,” Fluentum, Berlin, 2023, installation view

The starting-point of critical elaboration is the consciousness of what one really is, and is "knowing thyself" as a product of the historical process to date, which has deposited in you an infinity of traces, without leaving an inventory. ... Therefore it is imperative at the outset to compile such an inventory. [1]

– Antonio Gramsci, from the Prison Notebooks

The human desire for self-understanding has always relied on language- and image-based technologies to document, organize, and represent experience. As Marshall McLuhan noted in 1967, these technologies “do something to people”; they impact the body “chiropractically,” [2] constituting a particular ontological bias or what Donna Haraway would call a specific “situatedness” in history. [3] Loretta Fahrenholz’s current exhibition “Trash The Musical” at Fluentum in Berlin offers a critical examination of today’s AI technologies and their impact on human narrative identity. The works on display expose the affective potency of algorithmic multiplications, distortions, and mashups of human traces. In departing from the exhibition site’s architecture and history, Fahrenholz conducted a broader inquiry into the archive and its legacy.

Fluentum is a historical site from the Nazi era that has undergone several repurposings throughout the decades; amongst other things, the building has served as a base for the Berlin Airlift and as a film set for Quentin Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds (2009). In 2019, software entrepreneur Markus Hannebauer purchased the fascist neoclassical construction as a personal residence and as an exhibition space for video art. For her show “Trash The Musical,” Fahrenholz sectioned the space thematically into three parts – the entrance hall, the imperial staircase landing, and the upper floor – each problematizing algorithmic reproduction from a different angle.

Entering the ground floor, the viewer finds the walls covered with black-and-white C-prints of AI-generated images, affixed with archival paper clips. Fahrenholz’s series Once Upon a Time in Enemy-Occupied France (2023) shows renderings of various scenes from Inglorious Basterds, Tarantino’s telling of an alternate history of wartime Nazi Germany. [4] Fahrenholz’s series was created by feeding textual prompts to an algorithmic processing tool that generates new imagery on the basis of a curated image archive of innumerable online sources. The works are, in a sense, photographs visualizing algorithmic “thought process”: regurgitating fragments of actual World War II–era photographs of the Fluentum building and remixing them with parts of Tarantino film or production stills, the algorithm creates eerie, seamless assemblages from massive data sets, which in their simultaneous familiarity and strangeness elicit a repulsion and an allure. Their darkness and hybrid character feel uncanny, calling to mind the haunting quality of photographs, as Susan Sontag noted in her book Regarding the Pain of Others (2003). The decision to produce algorithmic renderings of a fictional re-narrativization of the very real atrocities of the Nazi regime feels both delicate and urgent, especially in the context of news media’s omnipresent coverage of ongoing war crimes: it bespeaks the problems of algorithmic production and rapid circulation of fake imagery, as well as its role in spurring extreme emotional responses, mobilizing political affiliations, and promoting counterfactual postulations about events unfolding in real time. [5] Once Upon a Time in Enemy-Occupied France juxtaposes Fahrenholz’s investigation of the historical traces inscribed in the building with pictorial representations and fictionalizations of its history. This juxtaposition reinvokes and expands on 20th-century Marxist media critique by highlighting the constitutive role that photographic technologies play in the formation of (historical) subjectivity – especially as affect-fueled tools of labor extraction and mass entertainment.

Loretta Fahrenholz, “Once Upon a Time in Enemy Occupied France,” 2023

Two symmetrical flights of stairs connect the entrance hall to the mezzanine of the enormous building and lead the viewer to the second series of AI-generated images. I need to make mistakes just to learn who i am (2023) [6] consists of framed photographs, apparently from different decades, that show groups of people picnicking outdoors. Remarkably, a second algorithm has mimicked the material-aesthetic specificities of photographic technology of any given era; figures are collocated in ways that reproduce societal narratives about group identity and accepted forms of sociality. Again, in these assemblages of private photographs, vintage advertisements, and recent imaginings of past social ideals, fictions are layered upon fictions; seamlessly combining heterogeneous narrative content, the pictures bear no resemblance to actual lived realities, yet create a sense of “truthiness” and a visceral viewing experience. [7]

Created with an older version of the AI generator, the series contains distorted renderings of hands and faces that evoke feelings of body horror. In its incapacity to render realistic organic shapes, the AI’s function is not yet “fully” developed. One can imagine what it would mean for the tool to generate perfectly naturalistic fictions: the underlying process of assemblage and its lack of qualitative discernment would be rendered invisible. Some authors [8] have expressed concern about the pedagogical impact of AI mashups, which, when generated unsupervised, often contain disturbing, nonsensical, and violent content that lacks a human moral compass informed by empathy, bodily memory, and emotional intelligence.

Also on the upper floor, one encounters an installation of mushroom-shaped lamps. These hybrid kitsch objects, scavenged by the artist (mimicking the AI’s method) from Kleinanzeigen (Ebay’s classified ad platform in Germany), are remainders of an interior design trend that began in the 1970s and aimed to “bring nature into the home.” In the context of the Nazi-era building and the pictured picnics, these objects echo fascist ideologies of Aryan racial superiority once promoted by paramilitary organizations disguised as nature-loving boy scout groups.

Loretta Fahrenholz, “i need to make mistakes just to learn who i am,” 2023

Historically, new technological discoveries have always carried a messianic promise for each affected generation, providing new models for conceptualizing the underlying structures of both nature and the human mind. Just as Jacques de Vaucanson’s duck [9] became emblematic of the Industrial Revolution’s mechanistic worldview (prefigured in the philosophy of Thomas Hobbes and René Descartes), the rhizomatic, networked structure of the mushroom makes it the ideal metaphor for the digital age. As it fits perfectly with the prevalent narrative about the universe as a hyperconnected, efficiently evolving, intelligent system, the mushroom has assumed the status of a contemporary fetish object. Consider representations of the Wood Wide Web [10] or the booming online sale of chaga tea as an ancient superfood: the mushroom’s ubiquity suggests the possibility of human optimization through technological advancement, culminating in utopian ideas of posthuman transcendence. Some of the mushrooms in Fahrenholz’s installation were whittled from wood, others are 3D printed; the variety of materials and techniques brings to mind how technological shifts across the decades have resulted in different conceptions of nature and of human consciousness. There is a dry humor in Fahrenholz’s performative imitation of AI’s scavenging mechanism, which on the one hand suggests that all scientific models exist to be replaced by new ones and, on the other, alludes to the human brain’s tendencies toward pattern recognition and confirmation bias. The mind’s propensity to project pre-existing models of the world in places they don’t necessarily exist is mimicked by the algorithm, which provides infinite recombinations of the same data, in which the contextual specificities of each piece of information are lost in an ahistorical assemblage. In her performative imitation of the AI, Fahrenholz problematizes such enmeshment with a tool that still lacks the ability to make nuanced distinctions.

Trash The Musical is, quite literally, the exhibition’s eponymous centerpiece: a large flat screen hovers above the half-landing of the imperial staircase, which connects the ground floor and mezzanine. Exerting the authority of centralized panoptic surveillance, this windowed “eye” sets the stage for Fahrenholz’s “musical.”

In contrast to operettas or variety shows, musicals present a dialogic narrative alongside the music. Trash is a layering of narratives about confronting legacy – an attempt to create meaning from what remains of the past. The work was composed from hundreds of gigabytes of video material entrusted to Fahrenholz by online performer Alicia McDaid, who, like thousands of other digital creators, both profits from and caters to the algorithmic promotion of her artistic labor. McDaid filmed herself while clearing out the house that belonged to her uncle – an artist and obsessive hoarder of objects as diverse as a human skeleton, paintings, cat-food receipts, innumerable rolls of photographic film, and self-help literature. Her performances include song and dance, conceptual scripted scenes, satire, sexually explicit content, improvised monologues, references to the exhibition context (“I heard that Quentin Tarantino has a foot fetish,” and diaristic confessions.

Loretta Fahrenholz, “Trash The Musical,” 2023, video still

Though empowering in their incredible vitality and female jouissance, McDaid’s works threaten to tip into a zone of compulsive excess or grief. A “technician of the spectacle,” [11] the performer celebrates the camera’s gaze, mingling horror with humor, meta-reference, and sensuality. Both intimate and alienating, Fahrenholz’s film is a polyvocal, intertextual composition that cleverly switches between aesthetic and semantic registers, weaving a set of disjointed self-expressions into a musical narrative.

The logic of algorithms on social media platforms favors particularly affect-laden images that generate more views, which various political and economic interest groups use to their advantage. Besides attesting to the potential for a creative dialogue with an AI interlocutor, Trash demonstrates the chiropractic effect of such an exchange by showing the extreme physical states that McDaid experiences: she fully embraces a cyborgian extension of herself in the context of the capitalist mass entertainment complex that feeds on the individual’s self-exploitation. Trash speaks to the atomization and isolation of the individual whose emotional needs remain continuously unmet. Neither McDaid nor her uncle address any*body* in particular, as each of them generates content for a different apparatus of labor extraction. [12] The personal fragments produced to appease the demands of self-help literature or social media make tangible the narcissistic frustration [13] brought forth by the prosumerist maxim to expand the self through prosthetic tools. Trash can be read as a dialogic, if not therapeutic, gesture in which an archive of disparate aspects of one single subject are assembled into a redemptive narrative. Engaged in dialogue, a subject can experience itself as meaningful. The exhibition seems to suggest that self-understanding, a “coming to terms” with one’s own existence, requires more than an archiving tool to engender emotional resonance, which is rooted in the experience of having a body. [14]

The show addresses several attempts at archive creation, including the Fluentum collection, McDaid’s videos, her uncle’s paintings, and Fahrenholz’s own works. In the paralleled narratives of two haunted buildings, the skeleton (which even accompanies McDaid in the back seat of her car in one of the film’s sequences) becomes a vanitas, hinting at the precarious simultaneity of the desire for remembrance and the fact that any collection of a life’s work may one day be discarded.

“Loretta Fahrenholz: Trash The Musical,” Fluentum, Berlin, April 26–July 29, 2023.

Luzie Meyer is an interdisciplinary artist, writer, and translator based in Berlin. Her work has been shown internationally, most recently at Kunsthalle Bremerhaven, Germany; Istituto Svizzero Roma, Italy; and the Kölnischer Kunstverein, Germany. She recently coedited the anthology Sibyl’s Mouths – A Pure Fiction Publication, published by Sternberg Press.

Image credit: 1. © Loretta Fahrenholz / Fluentum, photo Stefan Korte; 2-4. © Loretta Fahrenholz

Notes

| [1] | This quote also appeared as an epigraph in: Julietta Singh, No Archive Will Restore You (Goleta, CA: Punctum Books, 2018). |

| [2] | This Is Marshall McLuhan – The Medium Is The Massage, directed by Ernest Pintoff and Guy Fraumeni, episode of NBC Experiment in Television series (New York: NBC, 1967), film, 53:00. Available on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cFwVCHkL-JU. |

| [3] | Donna Haraway, “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective,” Feminist Studies 14, no. 3 (Autumn 1988): 575–99. |

| [4] | Which, in its own right, asserts the redemptive power of artistic fictions, as the Jewish protagonist helps lock up and kill the fascist leadership in a burning cinema. |

| [5] | Alistair Coleman and Shayan Sardarizadeh, “Ukraine War: Viral Conspiracy Theories Falsely Claim the War Is Fake,” BBC News, February 27, 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-64789737. |

| [6] | The title is taken from a lyric from the Britney Spears song “Overprotected” (2001). |

| [7] | Ben Zimmer, “Truthiness,” On Language, New York Times, October 13, 2010. |

| [8] | James Bridle, “Something Is Wrong on the Internet,” Medium, November 26, 2017, https://medium.com/@jamesbridle/something-is-wrong-on-the-internet-c39c471271d2. |

| [9] | Gaby Wood, “Living Dolls: A Magical History Of The Quest For Mechanical Life,” book excerpt, Guardian, February 16, 2002, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2002/feb/16/extract.gabywood. |

| [10] | Robert Macfarlane, “The Secrets of the Wood Wide Web,” New Yorker, August 7, 2016. |

| [11] | Caroline Busta, “Basic Instinct: Cyber-Channels and the Female Pose,” Texte zur Kunst 97 (March 2015): 120. |

| [12] | Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” in Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, ed. Hannah Arendt, transl. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken Books, 1969). |

| [13] | Bernard Stiegler, “§1 The destruction of primordial narcissism,” in Acting Out, trans. Daniel Ross, David Barison, Patrick Crogan (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2009), 39. |

| [14] | Julietta Singh describes the body archive as “an attunement, a hopeful gathering, an act of love against the foreclosures of reason” and “a way of thinking-feeling the body’s unbounded relation to other bodies.” Julietta Singh, No Archive Will Restore You (Goleta, CA: Punctum Books, 2018), 29. |