A CITY FOR ANOTHER COUNTRY María Minera on the Paradoxes of a Hyped Capital of Culture

“Paloma Contreras Lomas: Sombras nada más (Espíritu TV),” Pequod Co., Mexico City, 2023-24

In 2023, Time Out magazine rated the “charismatic, cosmopolitan” Mexico City the number one city in the world for culture and considered it best “for both the quality and affordability of its culture scene.” [1] This year, the city once known as “DF,” for Distrito Federal, again garnered a position on one of Time Out’s lists, ranking sixth out of the 50 best cities in the world for 2024, not to be missed this year for its “exciting emerging art spaces … new galleries … and eagerly awaited international exhibitions like Damien Hirst at Museo Jumex.” [2] Seven hundred years after its foundation at the heart of the Aztec Empire, this gigantic city, in addition to being “at the forefront of a vibrant gastronomic revolution,” scored highly “for its overall liveability, with 100 percent of locals naming the city beautiful, 96 percent saying they were happy there and 94 percent saying it’s easy to make friends.” [3] As if that were not enough, I would like to point to an additional advantage: Mexico City is one of the few areas in the country that has not yet been engulfed by an alarming sea of violence. During the days when the annual art fair, Zona Maco, is held, CDMX – the city’s awful new nickname, which was arbitrarily chosen by a previous mayor as part of a rebranding campaign in 2016 – bears a strong resemblance to many European metropolises: its museums – which indeed, as Time Out indicated, seem to be on every corner – offer exhibitions of the caliber one might find at the Fondation Beyeler, Palais de Tokyo, or Palazzo Grassi; its restaurants amaze diners with colorful dishes crowned by insects – a form of nourishment prized by the ancient Aztecs, who called them names unpronounceable to present-day tourists yet beautiful to any ear: azcamolli, xomilli, axayacatl. What makes the city even more desirable than Berlin or Paris is its unbeatable, eternally balmy climate, complete with jacaranda trees that paint its streets a luminous violet every spring.

Mexico City is, hence, a marvelous bubble. But it is also a capital that has turned its back on the reality of the vast surrounding territory that, by comparison, makes it look like Monte Carlo. Only a few miles away from the bustling fairs of the art world lies an immense territory, nearly a third of which is controlled by organized crime. The infamous cartels that television series have elevated as if they were intimidating yet charming bands of brigands rather than organizations that, in collusion with local authorities more often than not, control the movements of people and merchandise in bone-chilling ways, leaving dozens of ghost towns in their wake. Because in order to survive, many people have no choice but to abandon their homes and livelihoods from one day to the next, as if they were fleeing the lava of a volcano. Yet the reality, of fleeing a legacy of death and unspeakable terror, is worse. Mexico is a country that counts the dead caused by criminal violence in the dozens each day – many of them are women, victims of femicide. This is a country that no government, either left- or right-wing, has managed to pacify. In fact, a scenario of peaceful coexistence seems increasingly distant, now that the solution proposed by our politicians has been none other than a militarization which has proven to do nothing but perpetuate myriad forms of violence. [4] Extortion on the part of criminal organizations has spread to even the smallest enterprises, such as neighborhood corner stores or fruit and vegetable market stands, all of which must come up with all kinds of quotas in order to continue to do business. True, Mexico possesses some of the most beautiful beaches in the world. But they are difficult to access by highway, now that so many roads have become impassible because they are controlled by criminal organizations.

Teresa Margolles, “Muro Ciudad Juárez,” 2010, in “May You Live in Interesting Times,” 58th Venice Biennale, 2019

Our country is undergoing, therefore, a crisis that finds in a specific group its most terrifying and, at the same time, most admirable symbol: the so-called madres buscadoras, or seeker mothers. Women of all ages from states across Mexico leave their homes every morning to do what no authorities are willing or able to do: find their loved ones, who one day left home never to return. They start out by searching for them in penitentiaries, hospitals, and morgues, only to come up empty. No one ever knows anything regarding the fate of these women, these men. Over 100,000 children, spouses, and siblings, simply swallowed up by the earth. So the earth is where the seeker mothers go: to desolate fields, where they dig with their own hands in an attempt to find the tiniest sign – bones, a small medal, garments – that will at least give them the opportunity to close one small part of a never-ending cycle, given that, as they say, Mexico is no longer a country but “a mass grave with a national anthem.” [5]

This is the chilling light under which the contemporary art scene, concentrated almost entirely in the CDMX, ought to be examined, even if it is, according to Time Out travel editor Grace Beard, “redefining the boundaries of creativity, and that’s what makes it so vibrant.” [6] Paradoxically, she speaks the truth: the scene does possess “diversity and vitality.” These days, an exhibition of recent paintings by our most internationally renowned artist, Gabriel Orozco, is on view, as well as smaller but fascinating shows by emerging artists like Paloma Contreras Lomas or Wendy Cabrera Rubio, who are both, indeed, on a quest to “redefine the boundaries of creativity,” in order to consciously, critically try to answer the question of what can still be possible and relevant for a woman artist working on the global periphery to do in artistic terms. [7] Curiously, it has been women artists above all who speak out about the violence. One of the most prominent is Teresa Margolles, who since the 1990s has concerned herself with what she defined as “the life of the corpse” in a place full of corpses – a place like Mexico, where bodies pile up endlessly in public morgues as a direct consequence of our political and social violence.

However, artworks like those of Margolles – or Fritzia Irízar, Chantal Peñalosa, or the above-mentioned Contreras Lomas, among others – are clearly in the minority. Margolles was the artist chosen to represent Mexico in the Venice Biennale of 2009, where she chose to frame her participation as a question: “What else could we talk about?” And the “what” her question alluded to, that is to say, the “what” she exposed in the national pavilion, caused significant discomfort among those who opposed Mexico presenting itself in an international forum as the country it most definitely is, rather than some imaginary other place. Margolles filled the space with the subtle yet overwhelming presence of a violence that was becoming increasingly prevalent at the time: a blood-soaked flag and mud from the scene of a massacre; jewels decorated with small fragments of glass taken from the windshields of cars involved in a shootout; a sound recording of a landscape where all kinds of violent episodes had taken place; narco-messages embroidered in gold on bloody fabric; credit cards used to chop cocaine, bearing the photographs of people who had been executed.

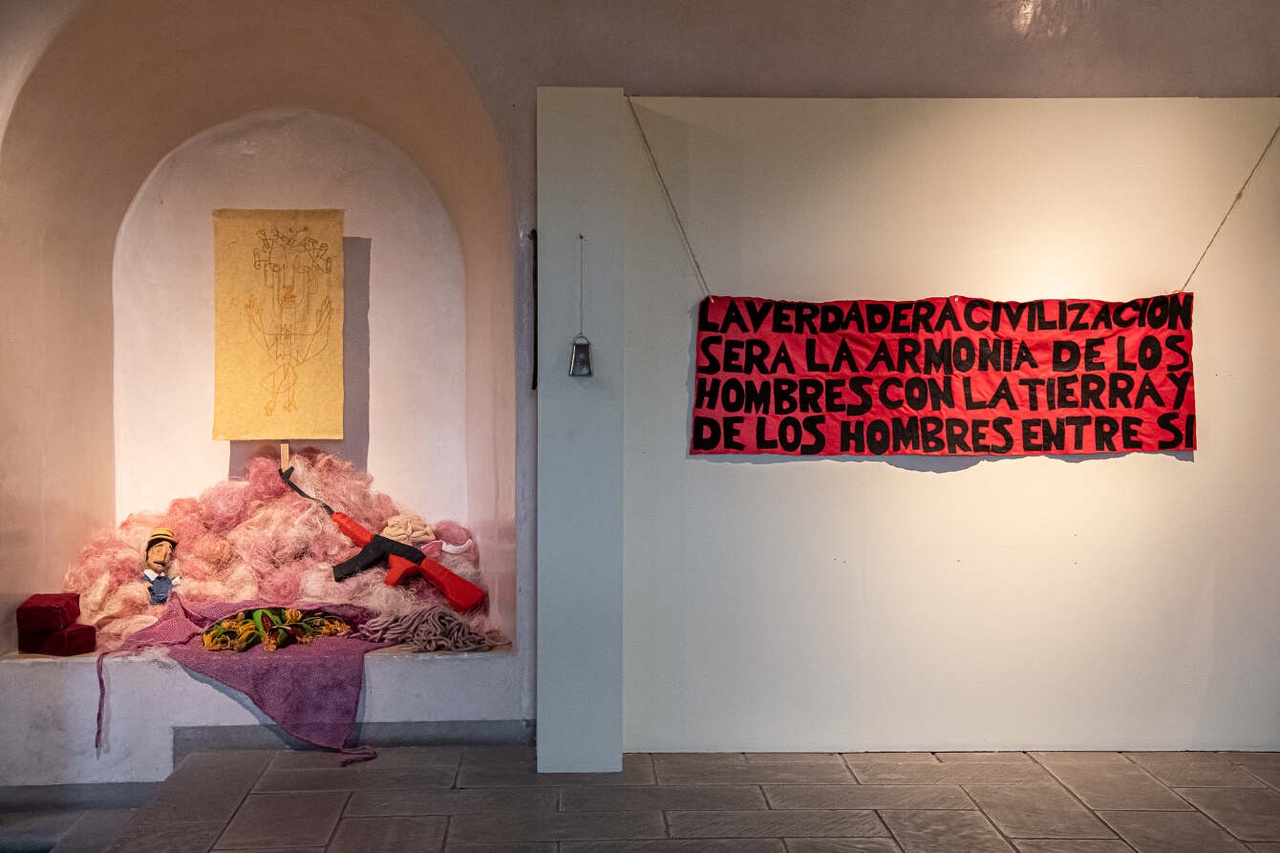

Wendy Cabrera Rubio, Manuel Delgado Plazola, Manuela García,“El que quiera comer que trabaje,” 2022, in “Promised Land,” Museo de Las Culturas de Oaxaca, 2022

Artists create the works they are willing and able to make. No one has the right to demand that art speak to the reality of a nation. And in the end, neither the artists nor their works are falling short: on the contrary, local art here is of an undeniable richness. Rather, it is the art world of Mexico City that has decided not to care. Here, we prefer to be moved by and protest wars that take place thousands of miles away (wars that deserve our empathy, of course), while our own violence does not move us. No one protests it. It has been normalized.

So yes, this city with a population of nearly 10 million is the capital of another country. One to which the art world does not have to turn a blind eye, one where a resident like me can read Time Out’s praise without feeling strangely guilty. Nothing I have written here is going to give pause, of course, to the scores of digital nomads who arrive from countries with minimal levels of violence to enjoy the enchantments doubtlessly provided by this metropolis, built hundreds of years ago atop a lake in accordance with the specifications of the gods by our ancestors, who in turn raised impressive palaces whose ruins may still be seen, or intuited, beneath the colonial architecture. I can only assume that these nomads are the ones anxiously awaiting an exhibition as dreary as the Hirst retrospective – who needs another embalmed shark, after all? But such is the contradictory nature of this city, where I was born and have lived all my life. I love it, I hate it.

Translation: Tanya Huntington

María Minera (Mexico City, 1973) is an independent art writer. Since 1998 she has published reviews and essays in a variety of cultural magazines and media platforms. She has also contributed texts to numerous books, including *Eduardo Terrazas: Equilibrio múltiple (Red de museos, 2023), Appearance Stripped Bare: Desire and the Object in the Work of Marcel Duchamp and Jeff Koons, Even (Phaidon, 2019); Anni Albers (Tate, 2018); Silvia Gruner: Hemispheres; A Labyrinth Sketchbook (The Americas Society, 2017); Drawing: The Bottom Line (S.M.A.K, 2015); Damián Ortega: Casino (Mousse Publishing, 2015); Contemporary Art Mexico (TransGlobe Publishing, 2014); En esto ver aquello (Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes, 2014); and Gabriel Orozco: Natural Motion (Moderna Museet, 2013).

Image credits: 1. Courtesy of the artist and Pequod Co.; 2. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Peter Kilchmann Zurich/Paris; 3. Courtesy of Wendy Cabrera Rubio, photo Jalil Olmedo

Notes

| [1] | Grace Beard, “The World’s 20 Best Cities for Culture Right Now,” Time Out, November 22, 2023. |

| [2] | Mauricio Nava, “Mexico City,” in “The 50 Best Cities in the World in 2024,” by Grace Beard, Time Out, January 23, 2024. |

| [3] | Nava, “Mexico City.” |

| [4] | In 2006, President Felipe Calderón launched the so-called War on Drug Trafficking; his successor, Enrique Peña Nieto, continued the failed projects with increased military efforts. The current president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who promised the opposite during his election campaign, now not only has the army deployed in the country but has also entrusted them with all kinds of strictly civil tasks. |

| [5] | An anonymous phrase that went viral not long ago and that is often found on demonstration placards and statements by search collectives. |

| [6] | Beard, “The World’s 20 Best Cities for Culture Right Now“ |

| [7] | The Orozco show is currently on view at Kurimanzutto gallery; Contreras Lomas’s show recently closed at Pequod Co., as did Cabrera Rubio’s at Salón Silicón. |