DIVERGING DREAMSCAPES Paolo Baggi on Peppi Bottrop at Sies + Höke, Düsseldorf

“Peppi Bottrop: Dream on,” Sies + Höke, Düsseldorf, 2022, installation view

Peppi Bottrop’s solo show “Dream on” gathered 22 paintings, all produced in 2022, and installed them throughout Sies + Höke’s nested gallery space in Düsseldorf’s Altstadt, including a new exhibition room in an adjacent building. The gallery’s entrance is a vestibule with large windows to the side street, which leads to the walk-through offices on the ground floor and, via a small staircase, up to a mezzanine. Hung on the left-hand wall of the vestibule was Bryny Blck, a 3.6-meter-high painting whose strokes revolve around a circular shape. Subsisting in an agitated atmosphere, this central element provides a gravitational anchoring and encloses its interior like a protective shell, as if to shield it from the surrounding, energetic streams. The contrasting treatment of the space inside the circle reinforces its isolation: here, the painterly strokes are more fragmented, laying bare larger parts of the canvas. On closer inspection, they also evoke a proto-figurative association, revealing a face inside the circle, or a full moon overlooking a flat landscape. The composition reminded me of the iconic poster for Georges Méliès’s short science-fiction film Le voyage dans la lune (1902), which features a wailing moon with a space capsule stuck in its right eye.

Bottrop’s painting presents a rich layering of his characteristic materials – acrylics, charcoal, soot, and graphite. Recurring in intricate superpositions throughout the exhibition, those materials establish a suggestive interplay of opposing qualities and connotations: while acrylics are largely associated with the finished painterly product, charcoal and graphite indicate a provisional stage. [1] Frequently used for studio drafts that precede an artwork’s final execution, such “basic” materials draw attention to the process of painting and, thus, to the painter’s presence.

Bottrop’s erratic technique and unpredictable brushwork are mirrored by the brittle characteristics of graphite, a medium that breaks easily under pressure. The soot, a result of an incomplete combustion of coal, is seemingly sprayed onto the canvas, indicating a strong relationship to processual painting: these compositions are not least the results of material behavior and natural processes. Substances and movements are imbued with agency. Along these lines, Bottrop’s works build up gestures that constantly posit and displace the painter and his position as author, between the intensity of the gesture suggested by the graphite and the uncontrolled projection of soot. The marks, which suggest a rapid painting process, create a rhythm similar to that of Albert Oehlen’s jazzy, virtuosic works. [2] The notion of the canvas as an energetically charged field of action relates back to painting’s capacity to store its own events [3] and carry a multitude of meanings in its gestural marks [4] .

Next to Bryny Blck in the vestibule, eight smaller paintings were hung in a grid-like structure, though the center position was vacant, thus repeating the centripetal arrangement of the adjacent work. Abstract forms that could be flowers or stars emerge from an entangled composition, seemingly springing from within.

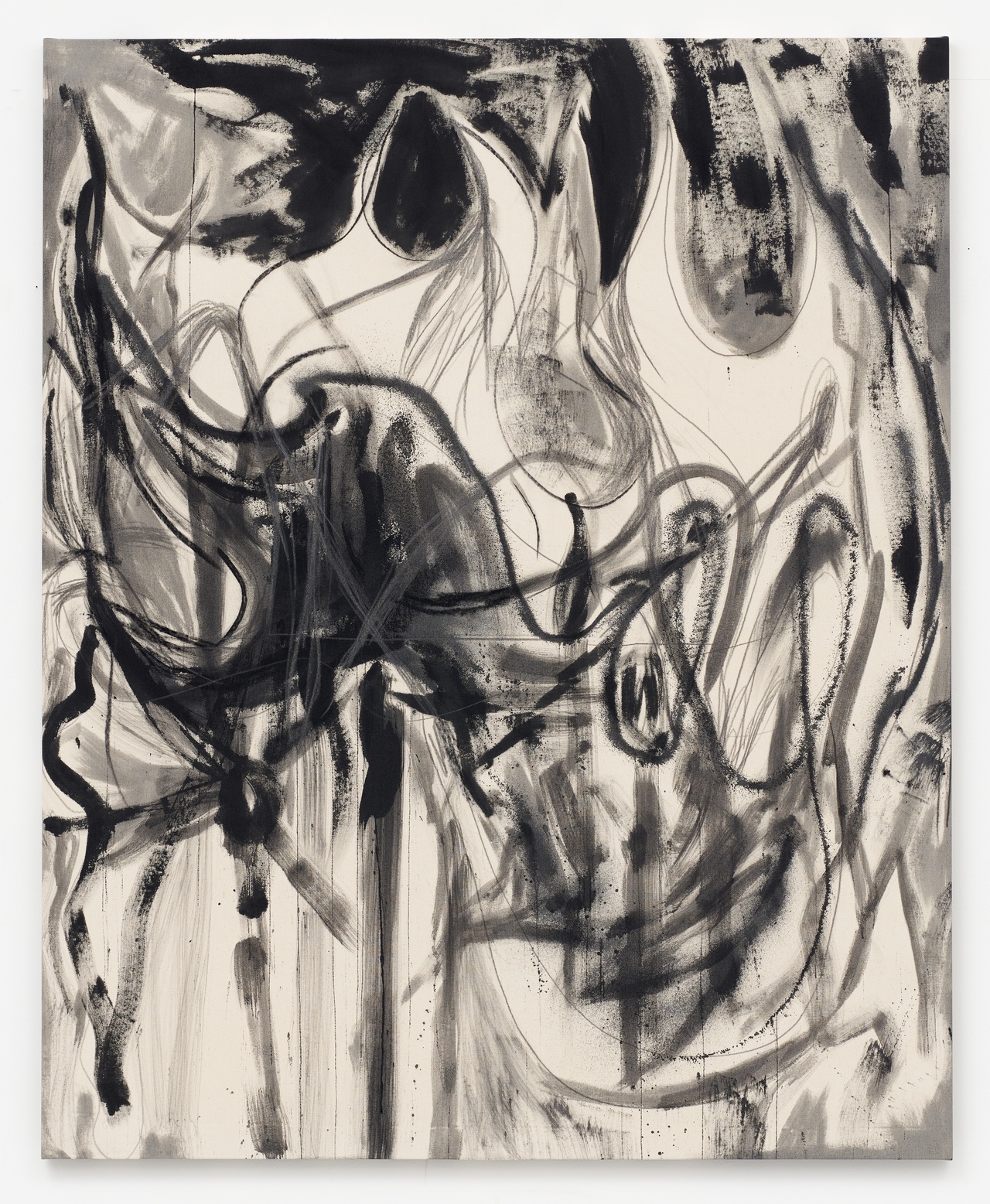

Peppi Bottrop, “Hllbr Grn,” 2022

Up the stairs, Hllbr Grn was composed of ripples and a rich reservoir of abstract gestures. In this painting, a tangle of undulating lines forms a kind of proto-calligraphy, yet resisting legibility or other forms of decryption. Larger patches in the upper part of the canvas recall drops of liquid waiting to be heavy enough to fall, which, however, at second glance disintegrate into loose strokes. The exhibition appeared to celebrate an in-betweenness – through the constant balancing act between painterly abstraction and figurative assumptions present in the works – which left visitors hovering in a dreamlike state of oscillation.

Poised between formulaic technicality and an absurdity reminiscent of the realm of half-slumber, the titles of all paintings in this show follow a logic that may be described as semantic subtraction. They omit all vowels, and possibly other letters from each word, creating a moment of halt in which the viewer tries in vain to construct meaning (four examples: McKnz’s wtr hmlck, Yw, Chrryl Lrl, Drpwrt Hmlck wtr). Both visually and verbally, Bottrop’s works appear to continue a notorious legacy, recalling the exclusionary implication of the “inside jokes” notably formulated by Martin Kippenberger to maintain the viewer in a troubled equilibrium between the incapacity to fully comprehend the joke while still being able to recognize it as such – a strategy that highlights the social and yet often exclusive mechanisms of art’s reception. “Dream on”: the title of the exhibition itself defies clear signification. It can both be read as a sarcastic injunction and romanticized call. As the artist himself shares in an interview published as part of the press release, the ambiguity of his work is achieved through movements of “juxtaposition and superimposition – confrontation and suspension, to the point of interruption.” [5] A tensile test then, rather than a balancing act.

Charcoal strokes, a recurrent feature in this show and a signature move in Bottrop’s broader practice, establish a firm link to the industrial Ruhr region the artist comes from. The connection is performative, as his chosen last name is that of his native city. His former professor Oehlen once introduced him as “Peppi from Bottrop,” and the name stuck. In addition to the geographical reference, it suggests an approximate art historical “localization,” situating the artist in the company of a certain group of West German (male) painters: apparently, Bottrop’s spiritual lineage goes back to the Cologne scene of the 1980s. [6]

In contrast to the Rhine metropolis, which was once Germany’s art capital, the city of Bottrop is mostly associated with its history in the coal mining industry. That said, Peppi Bottrop’s accumulated, somewhat unsettled marks may also be read in a more political (and possibly lyrical) context: the social body of the working class is historically determined through fluxes of individuality and communality; defying the pressure of alienation is to find a way for the group to be together. The community becomes an extended individual and the individual a concentrated community. [7] Hovering between decisiveness and hesitance, Bottrop’s strokes, too, maintain their singularity while formulating the bigger picture. Reading between Bottrop’s lines, they reveal traces of a very personal urban cartography and a psychogeography – a cultural technique that highlights interpersonal connections between humans and their built environments. [8]

“Peppi Bottrop: Dream on,” Sies + Höke, Düsseldorf, 2022, installation view

Back in the gallery, Bottrop’s exhibition continued on the first floor of the rear building, where five paintings were installed in a large rectangular room. Particularly impressive with its cinematic dimensions was McKnz’s wtr hmlck, a painting of the stately width of 3.2 meters and with about the same aspect ratio as the wall on which it was installed. Here, flower-like forms conflate with calligraphic ones in a crepuscular landscape. As if engaging in processes of transformation, flowers become jungle becomes groups of dancers. The soot turns some painterly marks into extinguished eruptions or detonations. The lower part of the canvas, with its horizon line grounding the scene, recalls a classic landscape painting. Or – maybe – a pastoral Ruhrgebiet? (Recent endeavors of renaturation have transformed the region quite a bit, many abandoned mines have given way to green recreational areas.) On closer inspection, the nature theme can also be identified in this show’s cryptic titles, which may well be derived from poisonous plants, stripping their names of vowels: McKnz’s wtr hmlck: Mackenzie’s water hemlock, Chrryl Lrl: cherry laurel (though an l has also been added), Sffrn mdw: meadow saffron (though inverted). If uttered, these titles would sound mumbled, slurred, perhaps suggesting a state of severe intoxication. Relating to rather robust, sprawling plants, they also reflect the vigor of the lines on these canvases – and the invasive flora that is claiming back the abandoned industrial sites in a former coal mining region.

Three smaller paintings appear to take up the plant theme, condensing it into a quasi-squared format. In contrast to the large-scale panel, they rather have the restrained effect of still lifes. Sharp lines sprawl across the unprimed canvases like thistles, like reminders of the thorny question of painting’s autonomy that is still up in the air.

What to do with all the displayed tension? While the paintings may at times appear like a closed system, it is at their breaking points and fissures that they can appear most convincing, when they reveal themselves less as virtuoso works of art than as vulnerable expressions of a subjective, transformative process. All their broken layers, loose ends, fragmented forms, gaps, and voids give just enough space for the bigger picture to form while allowing the drop, the line, the splash, or a certain material property to assert its precious singularity.

“Peppi Bottrop: Dream on,” Sies + Höke, Düsseldorf, September 3–October 25, 2022.

Paolo Baggi is an art historian and curator based in Brussels.

Image credit: Courtesy of the artist and Sies + Höke, Düsseldorf, photo Tino Kukulies

Notes

| [1] | See Gabriela Acha, “Blending as Resistance: Peppi Bottrop,”, Mousse, July 27, 2020. |

| [2] | Bottrop studied under Albert Oehlen in Düsseldorf; their respective interest in the figure of the line as the grounding element of representations was highlighted by a duo exhibition at the Marciano Art Foundation in 2018. |

| [3] | See, for example, David Joselit’s discussion about painting’s scoring capacity in David Joselit, “Marking, Scoring, Storing, and Speculating (on Time),” in Painting beyond Itself: The Medium in the Post-medium Condition, ed. Isabelle Graw and Eva Lajer-Burcharth (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2016), 11–20. |

| [4] | See, for example, Isabelle Graw, The Love of Painting: Genealogy of a Success Medium, trans. Brian Hanrahan and Gerrit Jackson (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2018). |

| [5] | “Transient Becoming: Peppi Bottrop in conversation with Christian Malycha,”, press release, Sies + Höke, September 2022. |

| [6] | Although Bottrop doesn’t seem to engage with this legacy in a critical way, as other painters related to the Cologne scene, for example Merlin Carpenter or Michael Krebber, have done. |

| [7] | See Carl Schmitt, Political Romanticism, trans. Guy Oakes [1919] (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1986. |

| [8] | See, for example, Anna Sinofzik, “Bottrop Grid,” in How Long is Forgotten, exh. cat. (Düsseldorf: Sies + Höke, 2020), 7–13. |