BREATHING IN THE INVISIBLE Polly Yim on Tiffany Sia at Artists Space, New York

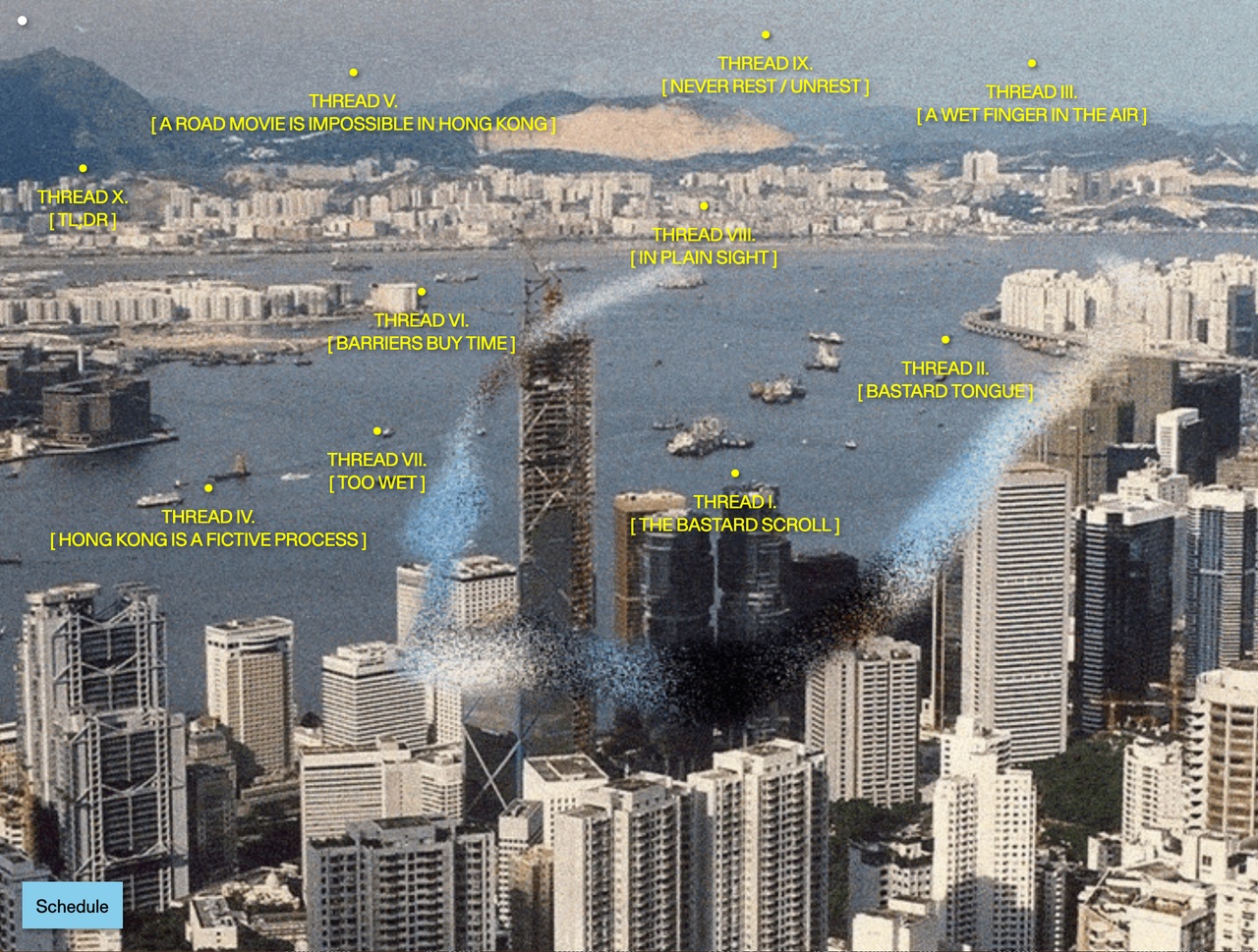

“Tiffany Sia: Slippery When Wet,” Artists Space, 2021, website view

Woven across ten multimedia works, Tiffany Sia’s first institutional solo exhibition deals with the aftermath of nearly a year and a half of mass protests in Hong Kong. Sia’s work beckons viewers from an indeterminate distance: whether seen online or in the physical, the works are conceived with a dispersed global community in mind, a reflection of Hong Kong’s considerable diaspora as well as the tenuous conditions created by the ongoing political crisis.

In 1998, one year following the British return of Hong Kong to Chinese control, cultural theorist Rey Chow described the Chinese view of the region as a “bastard child” [1] – culturally tainted by more than a century and a half of British colonialism and exposure to western liberalism. Denied authenticity and political legitimacy by China – and seen as a speculative vehicle of capital by the West – Hong Kong presents a diaspora now facing even further distances as its residents contemplate leaving Hong Kong due to a new era of fear under the 2020 national security law. Addressing psychic wounds and physical distances, Sia reclaims the illegitimate title in her exhibition works The Bastard Scroll (2021) and Bastard Tongue (2021), working to instill a sense of embodied agency instead of reinscribing disavowal.

Commanding attention and sculptural presence, the installation of The Bastard Scroll takes form in a long dot matrix printout stretched out across a dark wooden table, stacking neatly on an adjacent chair. Online, the dense collection of Sia’s writings – which reference everything from Dante’s Inferno to omens to postcolonial theory – demand a different sort of viewing modality through virtual scrolling. Reading requires extended duration, even endurance. In line with Hong Kong’s history as a proxy site for geopolitical struggle, The Bastard Scroll is positioned between a multitude of audiences – and the implicit power structures that come with their gaze. Eschewing the explanatory role of the native informant, Sia is well-armed for potential pitfalls in portraying what she terms “conflict narratives” to a Western audience. For the uninitiated viewer, the text’s legibility may vary by design: “For readers outside of here, this text asks you to simply bear witness as best you can, as much as you can commit to the labor of learning a place from far away, without everything defined for you.”

Tiffany Sia, “A Wet Finger in the Air,” 2021

This is not so much a performative repudiation of the Western viewer as it is a precaution – given the ways that images of flames, police, and teargas were broadcasted and consumed through the global media lens, Sia is wary of reproducing a spectacle of violence which is alluringly consumable and simultaneously numbing. Instead, the full text of Bastard Scroll, entitled “Too Salty Too Wet 更咸更濕,” deals with what lies outside the realm of newsworthy snapshots. This is an effort to bring the viewer closer, to lessen what Sia calls an “empathy gap” between spectators and Hong Kongers. Citing bodily records, Sia’s work traces marks of solidarity and collective trauma: of chemically-irritated skin on the arms of commuters, of cyclical insomnia and generational stomach ulcers, of what it feels like to grieve the death of a place that has no finite expiration date but only relentless duration.

In A Wet Finger in the Air (2021), three stacked television cubes sit in front of a dark column. On-screen, an assemblage of smiling weather forecasters, high humidity reports, and monsoons are interspersed with sponsored advertisements from Omega watches. Meteorological forecasts predict pressure fronts already risen and fallen: slipping in between luxury consumables, Sia raises a wet finger to judge the direction of the times, a corporeal weather vane of sorts. In contrast to the uneasy vantage points in Bastard Scroll and the unwritten latency in The Bastard Tongue, A Wet Finger in the Air seems like a suspended breath, a moment of recalibration to the aftermath of protests in Hong Kong. No longer in the media spotlight, Hong Kong’s state of crisis continues despite its departure from the global news circuits. In response, Sia asks herself: “How do you see this moment on the cusp of change?” [2]

The elegance in Sia’s artistic moves comes not out of an attempt to hold on to what is lost, but out of grasping at what seems to always be just out of reach. Livestreaming from March 14th to 20th in a series of episodic performative films titled A Road Movie is Impossible in Hong Kong (2021), Sia scales winding paths shrouded with dense subtropical foliage. Starting from the sandy Hong Kong shoreline at sunrise, the sound of her breath becomes more palpable as she climbs: the carried camera in motion smudges trees and fallen red flowers; its lens swings away from approaching passersby amidst narrow passages. Punctuating her steps forward, Sia pauses to turn the camera to look back at the shoreline over the course of her steep ascent and descent. The scenes strongly evoke a sense of speed that cultural theorist Ackbar Abbas coined déjà disparu: “a reality that is always outpacing our awareness of it, a reality that [...] film breathlessly tries to catch up with [...] as if every shot had to be closely attended to because things are always surreptitiously passing you by.” [3] Likewise, the projection Hong Kong is a Fictive Process (2021) invokes a destabilization of the image: a view looking out at the Hong Kong skyline shimmers – a blind spot of stochastic points which reveal the entire mirage.

Tiffany Sia, “The Bastard Scroll (detail view),” 2021

Both works capture a sense of upended time, a sentiment that deeply echoes Hong Kong’s historical trajectory. In 1984, the Sino-British Joint Declaration determined Hong Kong would return to Chinese control in 1997, leaving Hong Kongers in an intermediary power drift for over a decade. When the moment of the Handover came, a new deadline of 2047 would frame a new cycle of uncertain anticipation, preordaining the death of an autonomous Hong Kong under “One Country, Two Systems” as it left British hands. Foreboding dates and haunted in-betweens are ingrained in Hong Kong’s cultural canon, and it is no surprise that Sia’s work appears restless as it traverses a topography of mediatic moments, scars, and non-linear chronologies.

Yet make no mistake – while Sia’s work deals with themes frequently featured in Hong Kong cinema, her filmic language is immersed in the social and direct rather than romantic or nostalgic. As part of the North American premiere of her film Never Rest/Unrest in MoMA’s Doc Fortnight, Sia reflects on the global scale of spectacle in her special reading Crisis news is a genre film. She reads: “From the people who fly in for dark tourism; the financial institutions who are shorting in the background; real estate groups speculating the consequences on the global luxury real estate market, Hong Kong is dying; and its death became capital.” Cycling along an isthmus, the camera trails Sia from behind as she makes her way from Tai Mei Tuk (literally: “the very end”).

Shot from a mobile phone, Never Rest/Unrest depicts drones hovering above crowds before their censors are burned out by laser pointers; protest slogans are chanted in unison with gusto, and four-channel livestreams of protestors flooding out onto the streets play muted on a laptop screen. Yet moments of intensity are truncated by moments of stillness, even the mundane: a series of ghostly characters spray-painted onto escalator steps ascend and repeat; waves lap the rocky shoreline; a copy machine makes a black-and-white test print of a protest poster. Like Too Salty Too Wet, the proximity of the viewer to the protests is made apparent through the varying ability to contextualize what is depicted, and the resulting misreadings, gaps, or feelings of closeness can either serve to alienate or intrigue its audience.

Sia’s institutional debut is an invitation to the anti-spectacle: reaching beyond the mediatic, her work challenges us to remember that the act of viewing is implicitly powerful as crisis unfolds. Summoning a constellation of emotions, unseen moments, and vantage points, Sia’s work binds our affective experience to the global. As her voice reminds us, the times we are entering are sinister ones, and few have the possibility to seize the chance to be seen.

“Tiffany Sia: Slippery When Wet,” Artists Space, New York, February 17–May 1, 2021.

Polly Yim is an artist and writer based in Berlin. She recently completed a research publication, Aesthetics in Hong Kong Resistance.

Image credit: 1. Courtesy of Artists Space; 2. & 3. Photos Filip Wolak, courtesy of Artists Space

Notes

| [1] | Rey Chow, Ethics After Idealism: Theory, Culture, Ethnicity, Reading (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998). |

| [2] | Tiffany Sia, “Slippery When Wet: Tiffany Sia’s Poetry of Lived Time,” conversation with Emily Verla Bovino, Ocula, February 24, 2021, https://ocula.com/magazine/conversations/tiffany-sia-slippery-when-wet/. |

| [3] | Ackbar Abbas, Hong Kong: Culture and the Politics of Disappearance (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997). |