VISIONARY MACHINE..? Rachal Bradley on Peggy Ahwesh at Spike Island, Bristol

Peggy Ahwesh, “She Puppet,” 2001, film still

Two women, naked, mount a reposing male body. They are armed with blades. Smearing blood over his torso, they begin to French kiss. Taking turns, they play and inspect the man’s organ with their knives. It is playful and mocking; they do not touch him directly but inspect his flaccid cock from a distance. Is he dead? Is he pretending to be dead in a fetish game? Are they complicit and consenting? He is limp, reclined, eyes closed, the passive vessel of male desire.

This is the compelling and disturbing opening scene of Peggy Ahwesh’s film The Color of Love (1994) exhibited at Spike Island’s survey of the artist’s extensive career. Projected in a darkened screening space, the film, transferred to HD video, is an optical print of a black-and-white outré pornographic film dating from the 1960s. Ahwesh acquired the original 16mm film print in a damaged state and copied it frame by frame via optical printing, a process typically used in the film industry to combine special effects with real action or to restore degraded film. By inverting the optical print’s purpose, exacerbating the degradation of the film as opposed to “fixing” it, Ahwesh connects the viewer to the filmstrip’s very materiality. What we see are the chemical traces of the wet process, heightened damage, and the ruined emulsion bubbling into a cacophony of magenta and acid-green flora and fauna that frames the actors’ ironically serious black-and-white forms.

This particular method of reproducing the reproduction creates a constant tussle between the abstract patterns and the figurative bodies on the film surface, pushing away from the film’s heteronormative determination and toward its emancipatory potential as a speculative realm for the lived body. This process elicits the intrinsic quality film possesses to animate the dead via the living, the space in which a film work might function as a vision machine connecting the viewer with emancipatory states of desire. As Erika Balsom, the exhibition’s cocurator, writes, Ahwesh “repeatedly re-photographs single frames so as to break the illusion of continuity into gelid instants that recall the stillness of the filmstrip, the necrosis that underwrites cinema’s uncanny vitality.” [1]

Peggy Ahwesh, “The Color of Love,” 1994

The Color of Love sets out the ground that Ahwesh will return to again and again in further works on display in “Vision Machines.” While her aesthetically non-signature style is roaming, it is rigorous precisely because she returns to the limits of corporeality (social, symbolic, and biological), moving image, and technology. Ahwesh uses a variety of display devices and methods for the films, all made between 1993 and 2021: large-scale single-channel projections, multichannel video monitor stacks, an iPhone. In doing this, Ahwesh moves us between states of seeing: those of viewing, seeing oneself, and being seen by others. These points map out a structural architecture of vision. Not only a vision machine but the structural arc of image technology; a mechanism that has morphed the imaginary potential of moving image into a honed state weapon of digital surveillance, for example.

The optimism around the speculative capabilities of moving image for the lived body that are present in The Color of Love comes under pressure as early as 2001 in the work She Puppet (2001). The single-channel video work tests this idealism in virtual space. Ahwesh repurposes screenshots of her playing the video game Lara Croft: Tomb Raider. Croft dies repeatedly by elaborate means: shot by a bazooka and mauled by Arctic wolves and a giant tiger. Over and over again she exhales her last breath in an orgasmic release only to be reincarnated once more, emerging in a prison, a temple, a Siberian gulag. Ahwesh guides the viewer from behind Croft through this violent landscape, directing Croft to kill before being killed. There is a freeze-frame of Croft treading water in a lake, her ample pixelated breasts bouncing erotically on the waterline; she’s just trying to keep her head above the water.

Even if one has never played this video game, it is hard to escape the distinct dimensions of its protagonista, programmed by male coders. The characteristics of the digital revolution are expressed par excellence in Croft’s extreme virtual corporeality; the tiny waist, the full chest, the pronounced behind. It is difficult to read this as emancipatory. Yet Ahwesh sets Croft’s journey through this intensely violent landscape against voiceovers of three women reading a series of passages in the first person from The Book of Disquiet by Fernando Pessoa. Pessoa was a writer whose poetic modus operandi involved the full dispersal of authorial authority through an adoption of multiple heteronyms. There is an attempt to unite Croft’s overdetermined figure with the disembodied voices of the speakers, an act of conjuring a unity – a commons, a communal agency for the dispossessed, the ones who are only bodies, only voices.

She Puppet Sourcebook (2002) displays extracts from a larger sourcebook, constituting the research material for the video work She Puppet. Selected pages from the various resource materials are presented as photocopies mounted on the wall. It includes texts by among others Michael Taussig (The Nervous System) and Sadie Plant (Zeros and Ones), and reminds the viewer of the almost evangelistic belief that tends to accompany the idealism of technological advancement, one loaded with the power to emancipate the individual and social bodies into new forms of non-hierarchized communication and the dream of organizational principles of “non-mastery” capable of being communed in virtual space.

Peggy Ahwesh, “Smart Phone,” 2014

Ahwesh’s work in this exhibition displays her embedded and almost premonitory understanding of the potential of moving image along this exponential technological curve to be coopted for more sinister agendas. Perhaps this is rooted in her ethnographic approach, beginning with her fascination with the work of US anthropologist Ray L. Birdwhistell, particularly his film Microcultural Incidents in Ten Zoos (1971), a study of human interaction with animals at ten different zoos in seven different countries. [2] As Ahwesh describes, “I was always going for the microanalysis of human behavior. It’s all about those small gestures and micro-behaviors.” [3] This inevitably becomes a study of community and how gesture might operate as a social glue for widespread behavior. In more recent times, community has been highly financialized, underpinned by an accumulation of individual micro-gestures, in turn determining the trajectory and design of technological “advancement.” Guy Debord would be turning in his grave.

Insofar as Ahwesh uses her own lived environments as support systems for production, community forming is central to the methodology of Ahwesh’s work. The highly interdependent formulation of films such as The Scary Movie (1993) and The Vision Machine (1997) are palpably of a life that includes teaching, working cooperatively, engaging people in a complex academic body of work, and the articulation of ideas, themes, and codes that have distilled in tandem with process and material. These particular films use students as amateur actors and rely on their cooperation to succeed with the filmmaker, although they consent to being scrutinized and utilized in these absurdly funny projects, effectively, as puppets.

The trusting relations present in these collaborations are pulled into fragility in the video work Heaven’s Gate (2000–01). A single-channel video displayed on a wall-mounted monitor, it depicts a simple isolated presentation of words taken from the website of the titular cult organization. The cult’s beliefs in extraterrestrial contact led to their 1997 mass suicide. Ahwesh locates the word, as sign and image, within an ultra-logic of socially programmed instruction as they build with increasing paranoia on the screen. Here, the words are benign until abstracted into a constellation of meaning and power within the social body – potential weapons of mass destruction with entirely corporeal consequences.

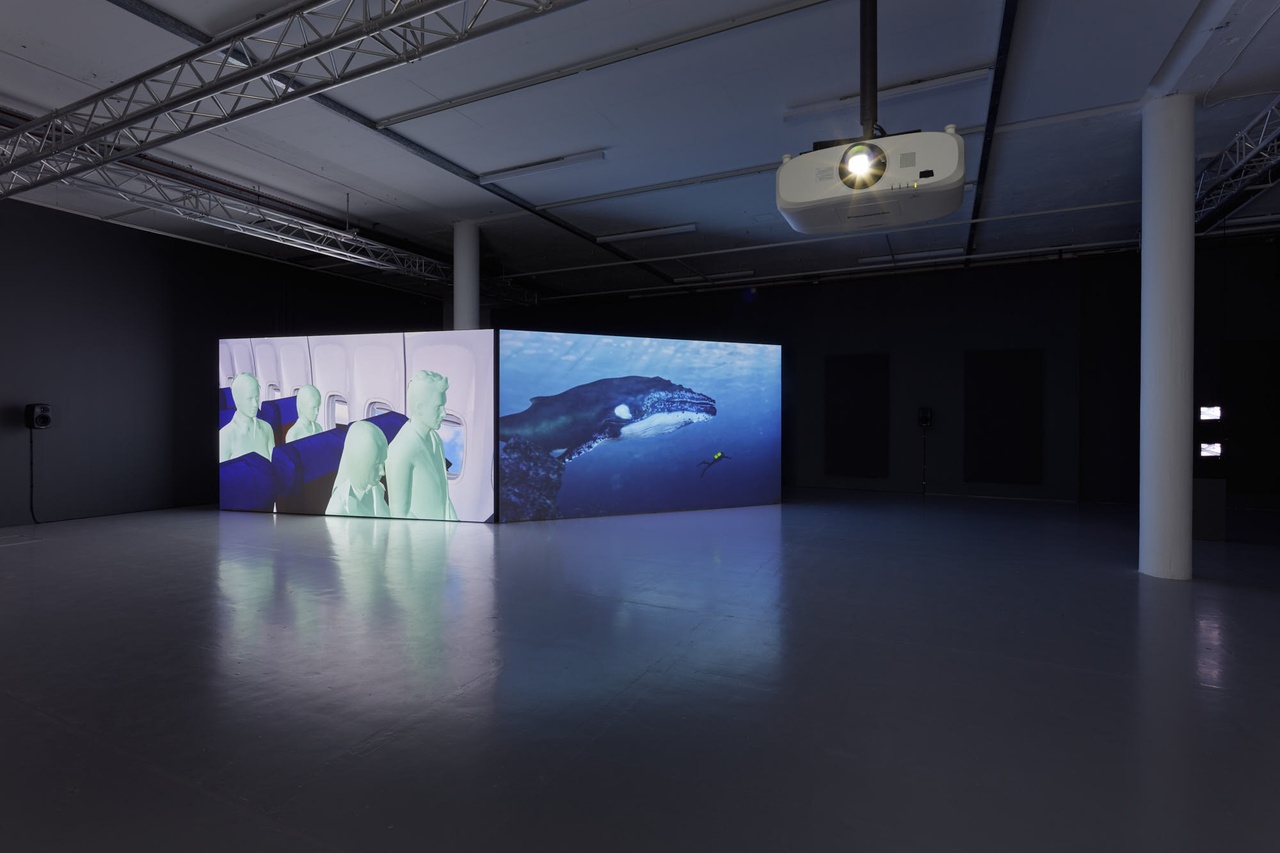

“Peggy Ahwesh: Vision Machines,” Spike Island, Bristol, 2021, installation view

Ahwesh’s more recent works seem to abandon the potential for radical community-forming. The contemporary moving image monikered here as computer-generated imagery is a far bleaker depiction of the intersection of the body under the grip of constant news coverage, streaming, and state surveillance engendered by technological capitalism. Verily! The Blackest Sea, The Falling Sky (2017) is a two-channel video installation. Footage drawn from a 24-hour news archive acquired by Ahwesh is organized into disjointed but recognizable and logical narratives that point to catastrophes for human existence. The first screen depicts the flailing outlines of humans, formally enhanced by CGI into rounded-off, smooth plastic avatars dealing with environmental fallout, repeated floods, and destructive consequences of the ultra-logics of profiteering in the technological race. The second channel shows computer-generated animation sequences using seemingly neutral directional graphics that ultimately point the bodies to state surveillance located by the characters’ connection to the “network.” It is as if the two channels are looped in a cybernetic nightmare of disturbing connective causes and effects: the cost and price of our technological revolution.

“Vision Machines” is the first such survey of Ahwesh’s work in the UK and Europe and conveys an intensely networked approach, each work functioning as a node in a cybernetic system. Precisely because of this, the exhibition illustrates how moving image technology has structured our desires, subjectivity, and citizenship, our very corpus, as individuals and as a social body. Proceeding out of gesture, are we really no longer the bodies in The Color of Love, exchanging spit, blood, tongues, and pleasure but instead abstract, now shiny surfaces, vessels of looking transacting on the level of sign, value, data, disaster, and crisis? Potentially.

“Peggy Ahwesh: Vision Machines,” Spike Island, Bristol, September 25–January 16, 2021.

Rachal Bradley is an artist and writer currently based in London.

Images: Courtesy the artist and Microscope Gallery, New York. 3 & 4: photos by Max McClure

Notes

| [1] | Erika Balsom, “Girlish Pursuits,” in Peggy Ahwesh: Vision Machines (Milan: Mousse Publishing, 2021), 22. |

| [2] | Ray L. Birdwhistell, Microcultural Incidents in Ten Zoos, 1971, https://mubi.com/films/microcultural-incidents-in-ten-zoos. |

| [3] | “Peggy Ahwesh and John David Rhodes in Conversation,” in Peggy Ahwesh: Vision Machines, eds. Erika Balsom and Robert Leckie (Milan: Mousse Publishing, 2021), 90. |