RETURNING THE GAZE Marcus Verhagen on Zanele Muholi at Tate Modern, London

"Zanele Muholi", Tate Modern, London, 2024-25

In 2008 the football player and queer rights activist Eudy Simelane was gang-raped, beaten, and then stabbed to death in Kwa-Thema, near Johannesburg. She was killed for living her sexuality openly. The 1996 Constitution of the Republic of South Africa was the first in the world explicitly to prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, but hate crimes, including homicides and so-called corrective rapes, which are meant to drive victims to conform to heterosexual norms, are appallingly common and often go unpunished in a country where many view homosexuality as sinful and “unAfrican.” [1] For decades now, the photographer Zanele Muholi has been working against this violence and the attitudes underlying it in both their artistic practice and their activism. One of the major strengths of this current mid-career retrospective at Tate Modern is that these two lines of activity are woven together throughout.

The exhibition begins with a series of early photographs capturing moments of intimacy in the lives of hate crime survivors in townships (Only Half the Picture, 2002–06), images made in the context of Muholi’s work with the Forum for the Empowerment of Women, which the artist cofounded. The final room is devoted to documents covering Muholi’s recent efforts to build institutions, such as Inkanyiso and the Muholi Art Institute, that support queer young artists and activists. It also includes photographs by the artist and their friends and associates of the weddings, funerals, and pride marches that mark and affirm ties in Black queer communities. Characteristically, the projects shown in both of these rooms are collaborative, Muholi drawing on extensive networks.

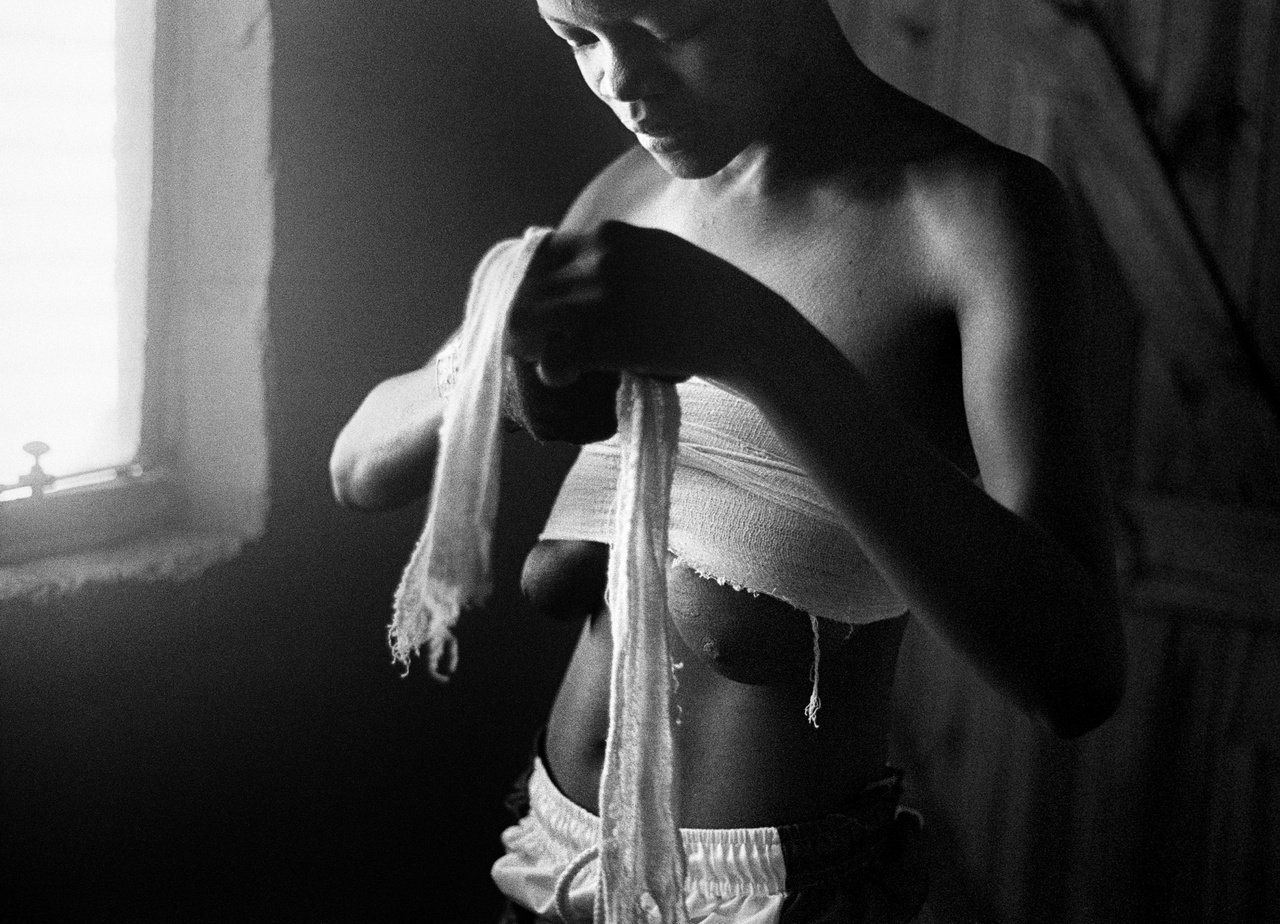

Zanele Muholi, “ID Crisis” (Only Half the Picture), 2003

Two of the largest spaces in the show are given over to two particularly ambitious and long-running projects, one of which expressly foregrounds Muholi’s friends and collaborators, or “participants,” as they call them. Faces and Phases, begun in 2006, consists of over 600 black-and-white portraits of Black lesbians and transgender and gender nonconforming individuals, who are shown from the waist up. The selection on view at Tate Modern is arranged in grids. Some sitters appear more than once, in pictures taken at different times (hence the “phases” of the title). Muholi has also left gaps in the grids to suggest that the project is incomplete and constantly evolving. The cumulative effect is potent: these figures may belong to minorities, but here they far outnumber museum-goers. Faces and Phases is not just an assertion of common purpose and solidarity but also a commentary on South Africa’s colonial and racist history. It is an archive of sorts and, as such, it gestures toward the photographic archives of colonial-era ethnographers, who used them to establish spurious typologies and provide pseudoscientific justification for colonial rule. But this archive, with its insistence on the stage presence and self-possession of each sitter, on specificities of posture and dress, forcefully invalidates the notion of classification by type. Just as forcefully, it challenges the viewing public, the sitters all looking out at us. Muholi has said that they are “returning the colonial gaze.” [2] But the boldness in some of the countenances here can also be read as an indication of confidence before the camera of an artist who is also an ally. The portraits owe their power in part to these expressions that convey defiance one moment and fellowship the next.

"Zanele Muholi", Tate Modern, London, 2024-25

The other major series is titled Somnyama Ngonyama (2012–ongoing), which means “Hail the Dark Lioness” in Muholi’s native isiZulu, and occupies a still larger space. The photographs on display here are black-and-white self-portraits in which the artist uses a variety of props and accentuates the contrast in tones to darken their skin as they reflect on both the politics of gender and the long tail of colonial rule and apartheid. The shots look back to ethnographic photography and its later variant in the pages of National Geographic, but where those photographers would capture men and women with “authentic” tribal accoutrements, Muholi uses ordinary, mostly domestic, objects as adornments: a tangle of branches, scouring pads, afro combs, a stool, and so on. In their ordinariness, the props serve to expose the dramatic, essentializing thrust of those earlier photographic practices. At the same time, many of the objects are symbolically charged. Muholi fashions elaborate crowns and accessories out of clothes pegs (Bester I, Mayotte, 2015) and scouring pads (Bester V, Mayotte, 2015) in memory of their mother, Bester Muholi, who supported her family through domestic work at a time when other lines of employment were closed to Black women. They picture themself wearing a tin helmet (Thulani II, Parktown, 2015) in allusion to the 2012 massacre of striking miners by police in Marikana; and they appear with pens stuck in their hair (Nolwazi II, Nuoro, Italy, 2015) in reference to the apartheid-era “pencil test,” according to which a person was classified as white if their hair was not curly enough to hold a pencil in place. These photographs open complex and disturbing historical perspectives, but they are also gripping as images, the artist often cutting a regal figure as they emerge from indistinct backdrops with their deadpan stares and elaborate DIY apparel. The images ironically revisit the concerns of ethnographic photography but also play on the protocols and pictorial panache of the fashion spread.

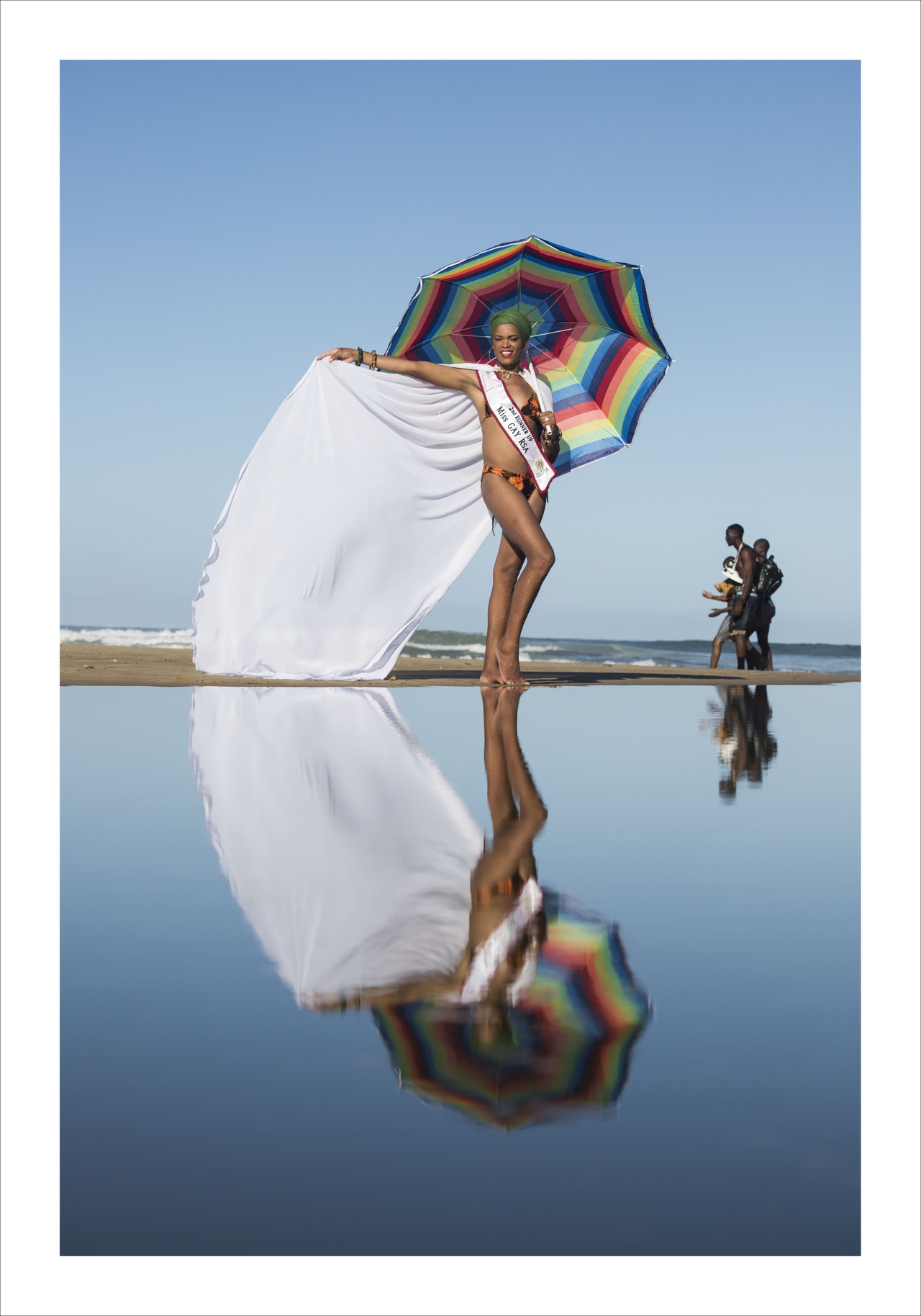

Zanele Muholi, “Mellisa Mbambo, Durban South Beach” (Brave Beauties), 2017

Faces and Phases and Somnyama Ngonyama together form the backbone of the exhibition. Alongside them are a number of other projects, such as Brave Beauties (2014–ongoing), photographs of Black trans women and non-binary people who participate in beauty pageants, and Beulahs (2006–10), color portraits of Black gay men and gender nonconforming individuals on beaches, which were once segregated along racial lines, and in other historically resonant locations. These works share with Somnyama Ngonyama an emphasis on play and invention as facets of self-presentation. And like Faces and Phases, though often more exuberantly, they give the artist’s queer friends and fellow travelers a chance to appear before the camera as they would like to be seen.

As befits an exhibition of an artist who is also an activist, the show is rich in information. In a compilation of filmed interviews, Muholi’s participants give insights into the day-to-day challenges faced by LGBTQ+ people in South Africa (Sharing Stories, 2019). They talk about how difficult it was to come out, about disapproving relatives, about facing down prejudice in the workplace, and about efforts to promote queer rights through drama, academic work, and pastoral duties. In another room, a timeline charts the rise and fall of the apartheid regime and key moments in the struggle against LGBTQ+ discrimination. Alongside the portrait of Busi Sigasa in Faces and Phases is a poem by the sitter in which she touches on the rape that left her with HIV, on her activism, and on her faith. Plainly, the artist and curators have gone out of their way to create a show that does justice to the works not just as artistic propositions but also as witness reports on historical and present-day abuses.

“Zanele Muholi” at Tate Modern, London, June 6, 2024–January 26, 2025.

Marcus Verhagen is a London-based art historian and critic.

Image credits: 1. + 3. © Tate / Isidora Bojovic; 2. + 4. © Zanele Muholi

Notes

| [1] | Rose Jaji, “Homosexuality: ‘Unafricanness’ and Vulnerability,” March 1, 2017, available at Social Science Research Network. |

| [2] | Quoted by Yasufumi Nakamori in “Queering Space through Photography: Zanele Muholi’s Colour Portraits,” Zanele Muholi, exh. cat. (London: Tate Publishing, 2024,) p. 97. |