WEAVING DIFFERENCES Sabeth Buchmann and Camila Sposati on Lygia Pape at K20 Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf

“Lygia Pape: The Skin of ALL,” K20 Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, 2022, exhibition view

“The Skin of ALL” is the first retrospective exhibition of the artwork of Lygia Pape to be held in a German institution. The show at the K20 Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen in Düsseldorf forms part of the institution’s principal research and exhibition project “Museum Global: Microhistories of an Ex-centric Modernism.”

Lygia Pape (1927–2004) was an artist active in Brazil from the 1950s. She was one of the founders of Grupo Frente (1952–56), a group that formed the core of the concrete art movement, which identified with the ideas of the Bauhaus school and Max Bill. After a schism with concretism, Pape became one of the cofounders of Grupo Neoconcreto (1959–61), which opposed figurative art, favoring geometric forms and pure colors. Such a group sense could be understood as both an artistic approach and as a way to protect one another, and a notion of collectivity as a form of defense of ideas made itself present from the outset of Pape’s practice.

Isabelle Malz’s curatorship of “The Skin of ALL” focuses on the interconnections between thought, ethics, and joy in the artist’s work, while also touching on sociopolitical issues related to Brazil’s period of dictatorship. The exhibition allows us to access the multiple media with which Lygia Pape worked and the connections between the artworks, since the use of different media points to their role in the transition from formalistic to conceptual and inclusive concepts of her artworks (making work with other artists or relating to the spectators). This transition has been made visible through the simultaneously chronological and circular structure of the exhibition – through both its physical installation and its discursive framing – which emphasizes the resonances between Pape’s different work phases.

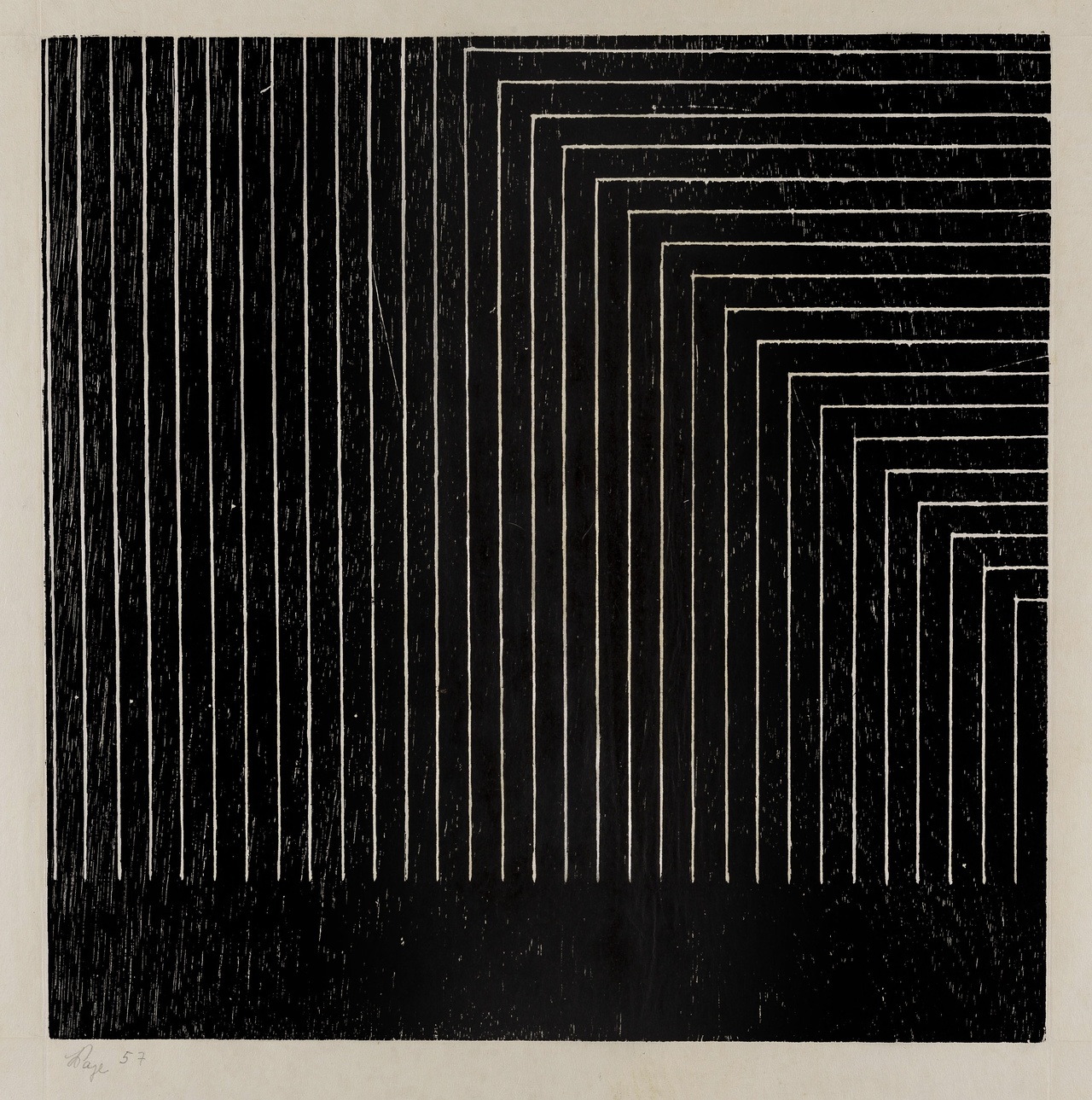

Lygia Pape, “Tecelar,” 1957

One of the exhibition’s great achievements is its revision of canonical Western historiography, as it demonstrates Pape’s early breaking up of formalistic pictorial languages through a literal concretization of materials and techniques, as happened in Brazil. This includes her attempts to achieve a non-illusionistic point of entry for a three-dimensional space within a two-dimensional image. The first room of the exhibition functions like an introduction to the role of geometric abstraction in Pape’s work. Its first item is an oil painting on canvas, Pintura (Painting, 1953). As much as it seems to result from a formally stringent combination of constructivist and post-cubist visual language, it comments – as do several other works from this period – on its own condition as a medium, “a painting,” and as such exudes an inviting sense of humor to the “entering” spectator. Tecelares (Weavings, 1953–60) are woodcuts whose linear patterns would later be recreated spatially as Pape experimented with her students, stringing and weaving thread between trees, in what would become the origins of the +Ttéia+ series. The installation titled Ttéia 1C (2002/2022), made with silver threads and probably her most celebrated piece, is also central to the first works in the show and interconnects with them, thereby attaining another magnitude. In Brazil’s northeast, the woodcut technique has been popularized by its use in literatura de cordel (“string” literature, inexpensively printed booklets traditionally hung for display from string). Here, the technique acquires a surprising aspect created by its printing on very fine and delicate paper. Pape’s choice of motif leaves no doubt about the importance of geometric abstraction – but her starting point is based on different, i.e., local traditions and genres, rather than European.

The larger exhibition hall contains paintings, drawings, reliefs, book-objects, an installation, photographs, multisensory experiments, poems, and Super 8 films that closely interconnect with each other. The objects are always oriented toward the idea of space in both a formal-dimensional and a reception-aesthetic sense: the books can be sculptural, the drawings can be activated three-dimensionally and can circulate. For example, Livro da Criação (Book of creation, 1959-60) is presented in an original version and a facsimile, the latter available to be handled by the public. A film from the same year shows the book’s sculptural qualities; in it, people are invited not only to touch the “Book of creation” artwork’s various elements but also to place and play with them outdoors, on the stones or sand near the beach of Rio de Janeiro, outside of an art context. The exhibition also contains a combination of book-objects, and Pape’s writing, presented on poems printed on banners, hangs in the exhibition space. These works demonstrate Pape’s concern with an art for everyone, capable of being activated anywhere, and with the synergistic field of her work as a socio-aesthetic whole.

Lygia Pape, “Livro da Criação,” 1959-60

Pape’s films constitute one of the core elements of the retrospective and show a pronouncedly activist attitude. The messages of political resistance against the civilian-military dictatorship in Brazil are direct, albeit manifested through poetic montage and subtle humor. In the films, Pape initiates a critique of “progress,” an idea pushed during the dictatorship, strongly linked to oil extraction and industrialization in an analogy of the creation of energy. The logos of the oil companies Esso and Shell appear in Carnaval no Rio (Carnival in Rio, 1974) and Arenas Calientes (Hot sands, 1974), films in which the artist’s political position against the authoritarian-industrial complex becomes explicit, although it is never verbalized. Music overlaps with the imagery, alternating and contrasting with passages of silence, which remind us that the military never allowed such protests. The Super 8 film Our Parents “Fossilis” (1974) shows the artist’s affinity with indigenous thought and her opposition to the concept of underdevelopment. We can see traces of Pape’s involvement in the conceptualization of the native Brazilian art exhibition Alegria de viver, alegria de criar (Joy of living, joy of creating, 1977), in collaboration with curator and art critic Mário Pedrosa, although the show was never realized, as the Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro, which was to host it, caught fire in 1978. That exhibition’s curatorial team brought together, among others, the social anthropologist Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, sociologist and politician Darcy Ribeiro, and the photographer Claudia Andujar, now important figures in understanding indigenous knowledge in Brazil and beyond.

The Brazilian aesthetic construction and its impasses relate to the Amerindian knowledge based on a radical perspectivism that – as, for example, in the case of groups living in Amazonia – challenges the Western tradition of anthropocentrism. It can be related, among other points of reference, to the Brazilian Antropofagia (anthropophagia, i.e., cannibalism) cultural movement in the 1920s, which addressed the devastating effects of patriarchal colonialism and which, in a new guise, experienced a renaissance in the 1960s and ’70s under the name of Tropicalismo, also very present in music and architecture. Pape’s film Catiti-catiti, na terra dos Brasis (Catiti-catiti, in the land of the Brasis, 1980), also the title of her master’s thesis, recaptures the consciousness of this artistic vanguard, the Antropofagia of the 1920s, perhaps the first phase of the “aesthetic construction” of Brazilian art. In a voiceover, Pape modifies the wording of the famous Letter of Pero Vaz de Caminha – a valuable historical document in which the Portuguese knight narrates his arrival in a “new land” and reports his travel impressions. The film is full of puns and double meanings, and its opening motif is of the iconic Abaporu by the Brazilian painter Tarsila do Amaral, the painting which gave rise to the Movimento Antropofágico after Amaral gifted it to the writer Oswald de Andrade, whom it inspired).

Pape consciously questioned how indigenous people were represented, and this is an important point of debate still valid in Brazil’s current artistic context. The latest edition of the Bienal de São Paulo (2021) included the most artists of indigenous origin in the history of the event, such as Daiara Tukano, Jaider Esbell and Uýra. Opting for the inclusion of indigenous artists is not a trend, but a sociocultural necessity that has been brought to light, essential for the structurally repressed confrontation of colonialism-based racism in Brazil. Another pressing point is that indigenous cultures can instruct us in a culture of non-accumulation of natural resources, an ecological understanding that the world needs to adopt. Here, “The Skin of ALL” would have had the opportunity to specify and update the sociohistorical from the perspective of those practices that Pape referred to.

Lygia Pape, “O ovo,” 1967, film still

It is worth mentioning that, during the dictatorship period, the Brazilan artist Lygia Clark was exploring the therapeutic capacity of art, while Hélio Oiticica had just started work on his Parangolé series (produced from 1964 to the end of his career), centered around an experimental cloak-like item of clothing that served as a social protection, bestowing upon its wearer the capacity to rebel against the repressive regime. Oiticica was a constructor in the most concrete sense of the word: someone who configured spaces in an attempt to transform “macro-structures.” Unlike many of her colleagues, Pape did not leave Brazil for exile abroad. Instead, she carried on teaching and continued to work with the heritage of Antropofagia by making skin the central medium of her “transorganic” works, expressed through a co-constitutive becoming of subject and object. Her film O ovo (The egg, 1967) documents this thought by transferring the radical constructivist concept of art to biology. At the same time, it implies an ambiguous rupture of the fine white coating of a three-dimensional piece – a cube, from which the artist emerges, and whose porous membrane connects the individual “egg” with its outer environment.

But just how close can we get to the utopian constructivism of Lygia Pape in an institution like a museum? The invitation to sensoriality, as a variety of her works are open to testing, touching, smelling, may not always be fulfillable in the museum environment. Instead, the K20 show overly ties the interaction of aesthetic and political concepts to a linear biographical narrative. In this structure, a sensorium for the complex impulses and activities that fed the experimental spirit of the broader art scene, into which Pape the autodidact entered, was a bit lost. What remains is a sterile representation of experimentality. How can the exhibition be loyal to the desacralization of the art object, Lygia Pape’s estate, and the museum at the same time? The artist’s films, of which, thankfully, a whole series can be seen, convey how the works could function in terms of their sensual core.

Lygia Pape anticipated a contemporary weaving of modern, popular, and indigenous art which refers to a culture that does not pretend to be greater than it is and that requires a dynamic with attentive spectators active in the world in which they live – the art they made.

“Lygia Pape: The Skin of ALL,” K20 Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, March 19–July 17, 2022.

Sabeth Buchmann is an art historian, critic, and professor of modern and postmodern art history at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna. She is co-editor of PoLyPen, a series on art criticism and political theory (b_books). Forthcoming publications include Kunst als Infrastruktur (Verlag Walther König, Fall 2022) and Broken Relations: Infrastructure, Aesthetic, and Critique (Spector Books, Fall 2022).

Camila Sposati is a visual artist and researcher born in Sao Paulo. She holds a Master‘s degree in Fine Arts from Goldsmiths College London and is a fellow of the Ph.D. program at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna. She published the book Stone Theatre (Revolver Publishing, 2016) and is currently taking part in the 37th edition of the Panorama da Arte Brasileira at Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo.

Image credits: © Projeto Lygia Pape and K20, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen 2022, photos Achim Kukulies