PARIS: PILLOW POLITICS Salomé Burstein on Portrayals of Masculinity, Structural Exhaustion, and Mattresses as Metaphors

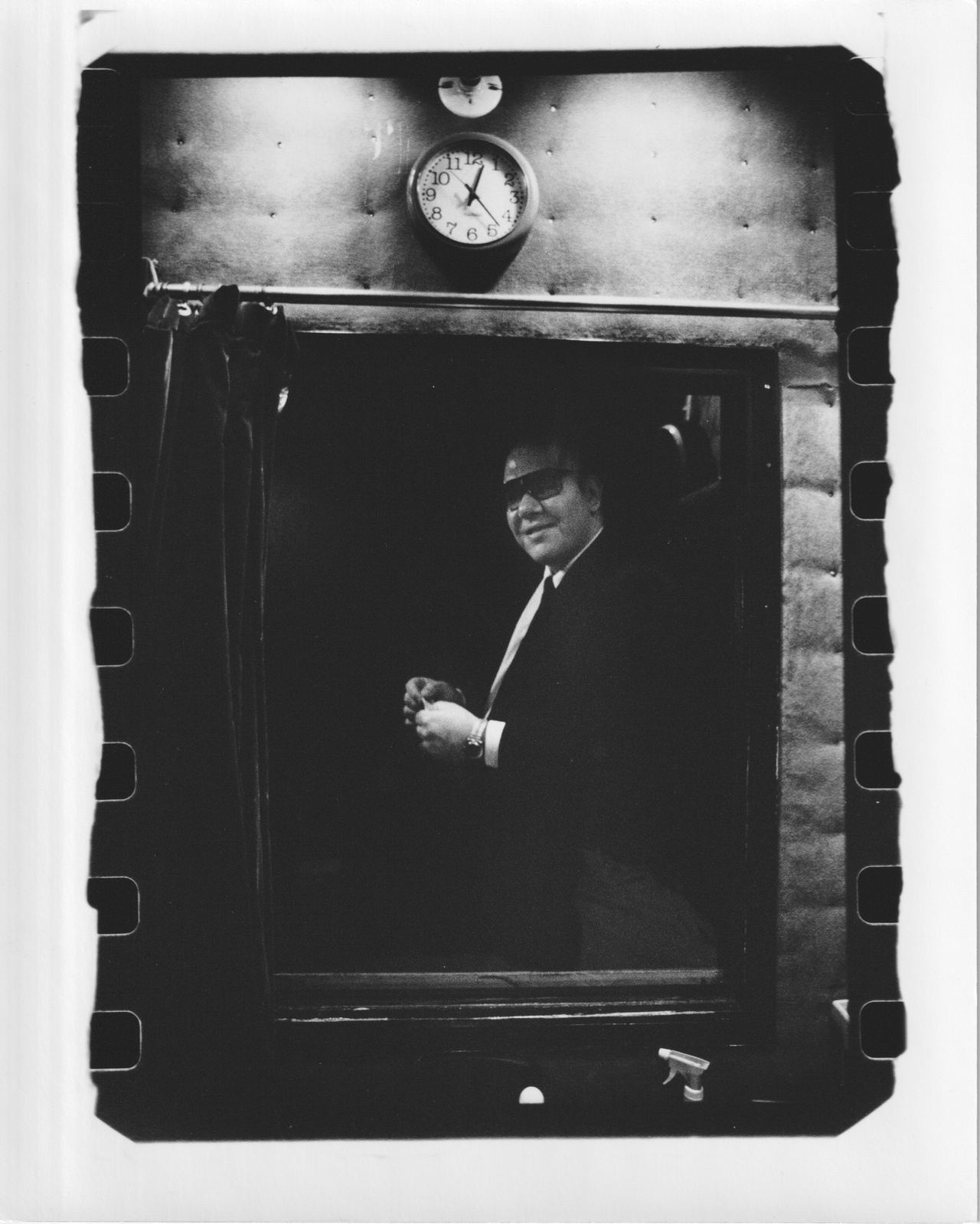

“Lili Reynaud-Dewar: Hello, my name is Lili and we are many,” Palais de Tokyo, Paris, 2023–24

I used to peep through the keyhole. Once bedtime came, unwilling to sleep, I tried to catch glimpses of the TV on the other side of the door that separated my sisters’ bedroom from my own. Almost every night, preluded by Groove Armada’s bossa nova–inspired theme, the romantic mishaps of four New York women unfolded on screen, and I followed through the narrow opening.

A pop culture epitome of early aughts white feminism, Sex and the City was my first encounter with a female author. Each episode was guided by protagonist Carrie Bradshaw’s voice-over. Consisting of fragments from her latest article, it was characterized by the specific rhetoric style of column-writing: an excessive use of puns, a light sense of intrigue, logical or heartfelt dilemmas which – when I binge-watched later seasons as a teen – seemed to oddly echo concepts discussed in my high school philosophy class: “Do we really want these things, or are we just programmed?” (Desire) / “Is timing everything?” (Metaphysics) / “In a relationship, is honesty the best policy?” (Ethics).

Cammie Toloui, “Untitled” (from the series “Lusty Lady”), ca. 1992

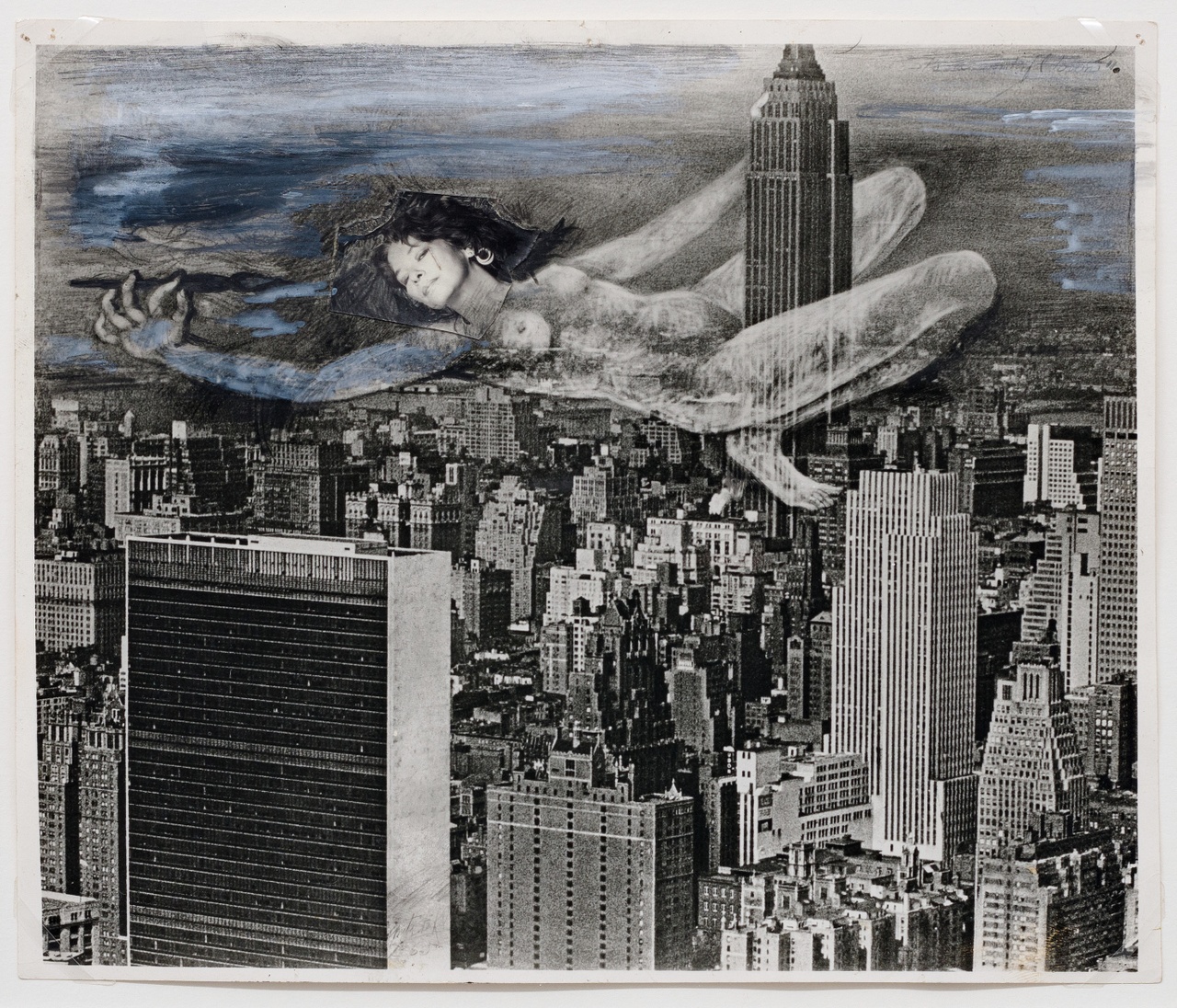

Sex and the City also featured my first ever examples of scenes where women were looking at men – without the show questioning what components of class, race, normative sexuality, and cisgenderism enabled its main characters to do so. I later came to wonder if my childhood peeping had somehow influenced my will to engage with erotic representations – especially of masculinity – in Western visual culture, in both my research and my curatorial practice. In the social environment I was part of in my hometown of Paris, I had come across a wider community of people sharing this interest. Whether through contemporary artists or projects pertaining to estates and archives, political exercises in gaze reversal had gained increasing attention. In early 2021, I joined Lusted Men, [1] a feminist initiative that gathers erotic photographs of men through a worldwide open call addressed to amateurs and professionals alike, with particular interest in portrayals of masculinities from a female perspective: projects like Rebekka Deubner’s “cum-lendar” (Couillendrier, 2022) – a visual investigation of male heat-based contraception in the form of an almanac – or Karla Hiraldo Voleau’s Hola mi amol (2019), a book composed of the photographer’s intimate encounters with men after her return to the Dominican Republic, compiling images that questioned “eroticism, virility, cultural and racial identities” [2] . I myself spent the last weeks of 2023 working on an exhibition featuring “The Dildo Man,” “The Cop,” “The Slug,” “The Roly-Poly” – all former clients of Cammie Toloui, whose portraits she took in the early 1990s, when working at San Francisco’s iconic Lusty Lady Theater strip club [3] . In the first days of 2024, I attended a performance by Reba Maybury at Fitzpatrick Gallery in Paris, in which the artist and political dominatrix reenacted an encounter with a sub of hers. The performance took place against the backdrop of the concurrent exhibition, curated by Juliette Desorgues, of Fight Censorship Group [4] member Anita Steckel, [5] whose works took over the metonymies of male power in satirical style: it showed the artist pole-dancing on skyscrapers or collaging her xeroxed face with drawn phalluses and floral wallpaper.

Anita Steckel, “Empire,” ca. 1969–73

Just a week earlier, I had visited Lili Reynaud-Dewar’s solo show at the Palais de Tokyo during its last opening hours. Through the foyer, behind the bar and bookstore, stood an array of half-unmade beds – bearing the traces of the bodies that had curled up onto them. These beds were in fact parts of replicas of Parisian hotel rooms. Almost identically furnished to the originals but stripped of their walls, the rooms evoked both the illicit decorum of love affairs and the sleep industry’s standardized design. Flat screens had been mounted above the beds, each displaying an interview with a different man, sitting or lying in the sheets of the original room. These men were all close friends of the artist, who had erased her presence by cutting her voice out of the video. I lay on the first free mattress I came across, stretched out a little. The clock was ticking: with the Palais de Tokyo’s doors soon closing, I could either linger some more on this bed or hop into the next. Catch quick glimpses of each man, pick quantity over a purposeful one-on-one. I decided to commit and spend some of the few minutes I had left with a rather young man in a sports jersey. He talked about lost loves and far-away friendships, about old parties and new joys of sobriety; about things left unsaid that call for confession. The bed was turned into a discursive device: by way of literal horizontality, the body position determined speech delivery, making language unfold in a pillow-talk style. I found myself tenderly attentive. Somehow, on this mattress, in the middle of a museum, something of an intimate experience was occurring. It was just the two of us.

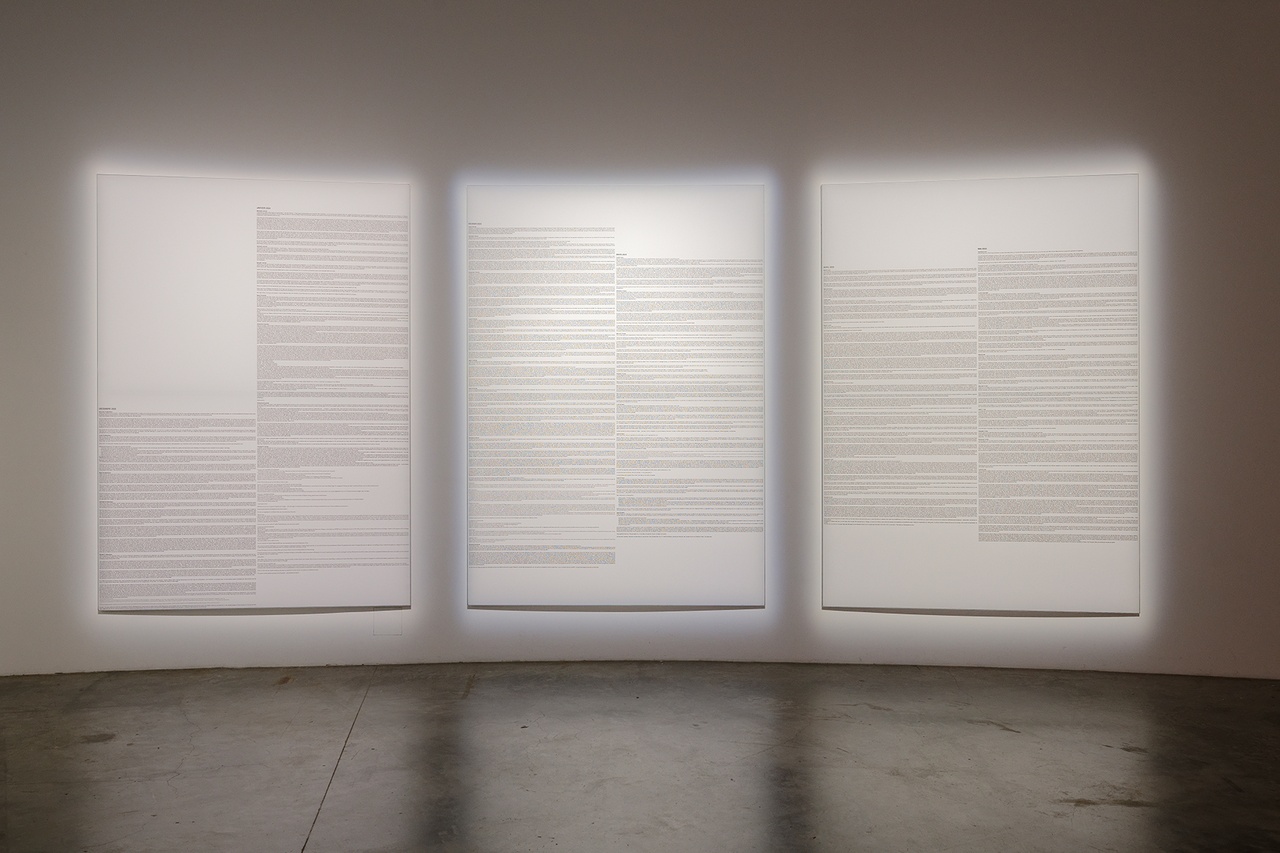

The illusion was only broken when, in one of his anecdotes, the young man discreetly mentioned “a guy you also know” – and that “you” wasn’t me, but a sudden reminder of the person behind the camera. Reynaud-Dewar had in fact never disappeared from the scene. Substituting orality with physical language, her silhouette danced around the beds in the form of video projections. And while the artist had purposefully erased her own words from the interviews, some of the walls had been papered with enlarged pages of a diary she had started when being commissioned for the show. Besides snippets of institutional critique in first-person writing – reflecting troubles with the art center, negotiations with the curator – the text contained everyday notes on coffees with fellow artists, on email conversations with students, on celebrations, anxieties.

“Lili Reynaud-Dewar: Hello, my name is Lili and we are many,” Palais de Tokyo, Paris, 2023–24

A little dazzled by the too many beds, by the too many words, I couldn’t help but think of SATC’s season 6, episode 7, also known as the “Post-It episode”: In it, protagonist Bradshaw wakes up the morning after a loving reunion with future-ex boyfriend Jack Berger – a frustrated author who struggles with her literary success – to find her love story cut short by a seven-word note placed on her laptop screen: “I’M SORRY, I CAN’T, DON’T HATE ME.” That same night, with her three friends, she visits Bed, a hot new club in town, whose furnishings are reduced to myriads of beds. Surrounded by pyjama-wearing waiters and Manhattan’s crème de la crème sipping cocktails on king-size beds, Bradshaw angrily recounts her morning humiliation, while Samantha looks around for someone to fuck – and coincidently spots three of Berger’s friends, sitting on the mattress across from her. Can New York really be such a small world?

Somewhat similarly, the sheer multitude of diary entries in Reynaud-Dewar’s exhibition circumscribed a tight-knit ecosystem: I recognized many names, names of friends, of friends of friends, of people I’d never met, but heard of. The texts on the walls mapped out a relational cartography of patrons and pupils, allies and foes, giving a good hint on how part of the French art world is structured – increasingly across cities, throughout physical spaces and transactional dynamics. A “circulation of information [usually] not intended for the public ear,” [6] these texts made transparent the mechanisms of an industry that capitalizes on interconnections and informality. In between the artist’s lines, one could read the depiction of a vampiristic milieu feeding on affects, a tyranny of structurelessness [7] that often blurs the borders between work and leisure, of business and pleasure – one necessary to balance asymmetries. This in mind, Reynaud-Dewar’s beds took on another meaning.

“Lili Reynaud-Dewar: Hello, my name is Lili and we are many,” Palais de Tokyo, Paris, 2023–24

Over the last few years, I encountered the mattress motif in a number of texts and exhibitions. Most often, it featured within critical analyses of neoliberal temporality and its domination processes, as the symbol of a “fucktory” [8] for reproductive labor; of an epidemic of fatigue unleashed by 24/7 capitalism; [9] of an unequal repartition of sleep depending on class, gender, and race. [10] Claiming rest as resistance, [11] the mattress became a means to subvert, in Bartleby-like fashion, the ethos associated with productivity culture. In the Palais de Tokyo’s dormitory, I now also read an illustration of structural exhaustion – one manifested by a proliferation of burnouts amongst cultural workers, whose rights are locally defended by initiatives such as La Buse, le Massicot or SNAP CGT. On February 14, the latter were, amongst other organizations, invited by the Assemblée Nationale to raise awareness about the precarity plaguing many members of the field. Their advocacy for more stable working conditions, against institutionalized invisible labor and a deeply-rooted view of the work of art as intellectual property, has resulted in the elaboration of a draft bill (first presented in 2022) and a booklet [12] written in collaboration with the cultural commission of the French Communist party. Both documents plead for access to unemployment insurance for visual artists, photographers, graphic designers, and writers, and for them to benefit from coverage for work-related accidents and illnesses. If successful, the initiative could incite structural changes in how art is produced, conceived of, and circulates.

The Palais de Tokyo’s door closed. I kept thinking about rumors, confessions; about explicit public demands; about the many different groups that make up the Paris art scene and how we talk about art, talk about ourselves, building a network of whispers growing louder, speaking volumes. I pondered weariness and thrill, the labor of being passionate, the sacrifices it takes, the romanticism it summons. I reflected upon this professional love-hate relationship which causes some to take a break, forces others to quit altogether, and everybody to, at some point, ask themselves – in a Bradshaw-style dilemma: What does it take to truly commit?

Salomé Burstein (1995, she/her) is a Paris-based independent curator whose work focuses on affects, eroticism, attentional structures, and transactional dynamics. Alongside conducting research in theater and visual studies (Ecole Normale Supérieure de Lyon, EHESS in Paris, Columbia University in New York), and investigating collective practices (Royal Institute of Art, Stockholm), she has collaborated with several artistic institutions (Council, Lafayette Anticipations) and publications (Klima, Habitante, alei journal, JRP Editions) through texts, interviews, and translations. She is also the founder of Shmorévaz (October 2021), an independent art space, located in a vacant former shoe store, dedicated to international art practitioners and publishers.

Image credit: 1. Courtesy of Lili Reynaud-Dewar, photo Aurélien Mole; 2. courtesy of Cammie Toloui; 3. © The Estate of Anita Steckel, courtesy The Estate of Anita Steckel, Ortuzar Projects, Hannah Hoffman Gallery, photo Peter Mochi; 4 + 5. courtesy of Lili Reynaud-Dewar, photos Aurélien Mole

Notes

| [1] | Artists, researchers, and curators Lucie Brugier, Marion Chevalier, Laura Lafon, and Morgane Tocco. |

| [2] | From the artist’s website. |

| [3] | The Lusty Lady Theater is famous for its 1996 strike and unionizing movement led by the club’s dancers and employees, resulting in them buying back the building in 2003. The movie Live Nude Girls Unite! (2000) by Julia Wallace Query powerfully documents the unionizing process. |

| [4] | The Fight Censorship group, whose first meeting took place in Anita Steckel’s studio on March 8, 1973, gathered feminist artists fighting specifically against the censorship of explicit art produced by women. It included Louise Bourgeois, Martha Edelheit, Joan Semmel, and Hannah Wilke, amongst others. |

| [5] | “LUST,” a solo exhibition by Anita Steckel, curated by Juliette Desorgues, first shown at Wonnerth Dejaco, Vienna 2023, then at Fitzpatrick Gallery, Paris. |

| [6] | Silvia Federici, “On the Meaning of ‘Gossip,’” Witches, Witch Hunting and Women (Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2018), 41. |

| [7] | Jo Freeman, “The Tyranny of Structurelessness,” in The Second Wave 2, no. 1 (1972). |

| [8] | Beatriz Colomina, “The 24/7 Bed: Privacy and Publicity in the Age of Social Media,” in How to Relate: Wissen, Künste, Praktiken / Knowledge, Arts, Practices, ed. Annika Haas, Maximilian Haas, Hanna Magauer, and Dennis Pohl (Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 2021) 186–200. |

| [9] | See Jonathan Crary, 24/7 Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep (London: Verso Books, 2014). |

| [10] | On this specific point, see the work of Black Power Naps, a duo composed by Navild Acosta and Fanny Sosa. |

| [11] | To quote the slogan of Nap Ministry, an organization invested in “the liberating power of naps,” founded in 2016 by Tricia Hersey. |

| [12] | Pour une continuité de revenus des artistes auteurices [For a continuity of income for artists and authors]. The text can be downloaded here. |