HOW TO NEVER HAPPEN AND SUCCEED IN DYING OUT Sophie Barshall on Graham Wiebe at Final Hot Desert, London

“Graham Wiebe,” Final Hot Desert, London, 2025

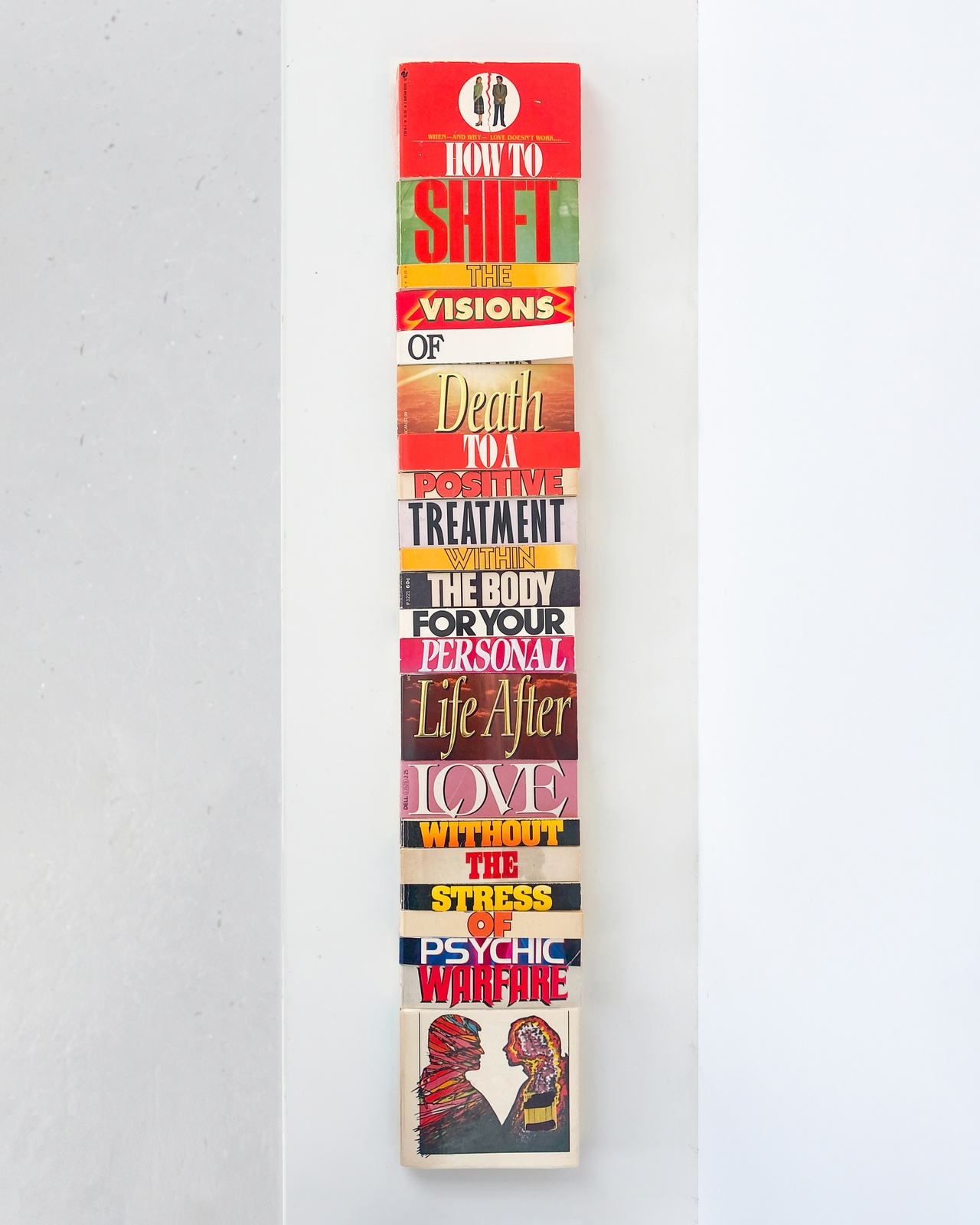

Over the last three years, Graham Wiebe has been sourcing secondhand self-help books from his hometown of Winnipeg, Canada. He hand-cuts these into fragments that isolate words and images from the books’ titles on their front covers. In his studio, over months, he then recombines the fragments into sculptures. Final Hot Desert, an artist-run apartment gallery in East London, presents 13 such sculptures – the first time works from the series have been shown together in a solo exhibition. They rest on narrow white shelves tracing the perimeter of the room in an almost museological display, extending into a single, central freestanding unit. Each book-sculpture lies flat, cover-side up. The resulting collaged texts form the works’ titles. One reads, for example, HOW TO SHIFT THE VISIONS OF Death TO A POSITIVE TREATMENT WITHIN THE BODY FOR YOUR PERSONAL Life After LOVE WITHOUT THE STRESS OF PSYCHIC WARFARE (2024).

Most of the self-help books Wiebe sources date from the 1970s to the 1990s and share a uniform format. Newer titles tend to be inconsistently proportioned, irregularities that would undermine the resulting sculptures’ likeness to books. Although self-help books have unique designs to stand out from one another, they share a general typographic and visual aesthetic that is brought into focus by Wiebe’s ceaseless recombinations. Jewel tones on cream backgrounds dominate, set in decorative typefaces with italics, drop-shadows, and emphatic capitals – a style now distinctly vintage. All carry titles beginning with “How To”, and symbolic or quasi-cosmic images appear: a cherub, an alchemist’s emblem radiating light, a castle looming on a mountain. One sculpture bears a line drawing of a human profile dotted with numbered points, almost like an acupuncture chart. Another shows letters and numbers spilling from a paper package, as if unwrapped to reveal their hidden significance. His sculptures also elongate the original format, underscoring the surplus of the genre itself.

While the modern genre of self-help originated in the 19th century, with the eponymous title by Samuel Smiles (1859), it only became a cultural phenomenon in the first decades of the following century. Titles like Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People (1936) linked personal success to confidence, salesmanship, and the “right attitude.” This popular literature drew on an ideal of self-fashioning that originated in the Renaissance, as well as the industrial era’s libertarian values of ambition and self-reliance. By the 1970s, countercultural currents reshaped the genre: Eastern-influenced spirituality, alternative healthcare, and self-actualization fused with ambitions of material self-advancement. During the onset of neoliberalism in the 1980s and ’90s, these strands hardened into a pseudo-spiritual rhetoric of performance and efficiency, reframing happiness and success as a matter of productivity. Today the language persists in practices such as affirmations and manifestation, but often recast as lifestyle management, from mindfulness apps to biohacking regimens. However, the underlying model – that change is an individual responsibility – has not shifted. As Micki McGee argues, this produces the “belabored self,” caught in cycles of exertion and evaluation, [1] while Eva Illouz observes how the therapeutic lexicon depoliticizes social problems by rendering them matters of private self-management. [2]

Graham Wiebe, “HOW TO SHIFT THE VISIONS OF Death TO A POSITIVE TREATMENT WITHIN THE BODY FOR YOUR PERSONAL Life After LOVE WITHOUT THE STRESS OF PSYCHIC WARFARE,” 2024

At first glance, Wiebe’s sculptures appear parodic, mocking a genre already bloated by its own sameness. HOW TO BUY BACK THE TIME YOU’VE LOST FROM THE HOPE OF SELF-HELP AND HELP YOUR SELF MAKE A LIVING (2025) folds its premise back on itself: The idea of reclaiming wasted time on self-help becomes inseparable from the act of wasting more of it. The humor lies in exaggerating the genre’s iterative and recursive logic, where each promise is little more than an absurd variation on the last. The sculpture features an image of a baby pram topped by a rising graph line. Set against the absurd title, the image reads as part of the parody: a symbol of women’s assumed reproductive duty and a caricature of upward mobility.

But humor is only the entry point. The sculptures are surprisingly moving because their titles also speak to today’s anxieties. HOW TO PREPARE YOUR HEART FOR the HATE OF SELF-IMAGE and THE COMPULSIVE SUFFERING OF SELF-LOVE (2025) stages the compulsive loop between self-improvement and self-loathing. How to be an EFFECTIVE NOBODY IN TIMES OF COMPLETE SPIRITUAL DISASTER WITH FAITH in THE ART OF SELF-HYPNOSIS FOR YOUR PERSONAL RETURN TO POWER! (2025) treats psychic collapse as healing. The titles verge on nonsense yet remain legible as self-help. By recombining dated books, Wiebe contemporizes them – what might in their original form have felt like clichés now surface as refracted truths of the present.

Wiebe’s durational process suggests an almost obsessive persistence, emphasized by meticulous hand-cutting and collaging. Though profoundly analog objects – all bear marks of use, such as warped covers and curling corners – Wiebe’s treatment of the books recalls the operations of digital technologies, or even the procedural logic of AI, which will inevitably author the genre’s next iterations: extracting, fragmenting, and recombining material. Quantity becomes an aesthetic principle, echoing Kenneth Goldsmith’s claim that in the digital age “quantity is the new quality.” [3] The 13 sculptures on view are composed from, by my count, 213 mass-produced originals, their charge depending on recognizability, circulation, and recombination. Don DeLillo’s White Noise (1985) offers a literary analogue: the supermarket as a chapel “full of psychic data,” where sheer recurrence produces atmosphere. [4]

“Graham Wiebe,” Final Hot Desert, London, 2025

Like Seth Price’s How to Disappear in America (2008) – a compilation of contradictory strategies for dropping out of mainstream society based on 1960s countercultural handbooks, which also exploits “How to” titling [5] – Wiebe’s sculptures show that withdrawal from self-management is rarely realized. Price and Wiebe also play into a certain type of Americana: the fantasy of escape and reinvention that originated with the 19th-century frontier myth of “going west” to start anew – a fantasy echoed in Final Hot Desert’s early programming, rooted in its beginnings as a nomadic project in the Utah desert, a landscape marked by Mormon pilgrimage, countercultural communes, and nuclear testing. A title such as Wiebe’s How to NEVER HAPPEN AND succeed in DYING OUT (2025) frames disappearance as victory, yet the books – and the system they reflect – are profoundly material, and impossible to vanish. A related sensibility surfaces in angelicism01, an anonymous online project that reframes extinction as a “POV” (point of view): In the montage Film01 (2023) digital images are treated as fragile traces of human presence, capturing mundane gestures as if they were last testimonies before disappearance. [6] In their view, these documents are not neutral records but relics reframed by the looming sense of apocalypse, where every act is tinged with finality. Clips of women making the bed or preparing a smoothie, for example, can be interpreted, according to Angelicism01, as an expression of the undying wish for productivity and the attempt at self-management, in a system which offers no release – even in the face of impending collapse. [7] Wiebe extends this ambivalence regarding systems of control into the material register of self-help, where the impossibility of disappearance is underscored by the stubborn physicality of the books themselves. This impossibility recalls Theodor Adorno’s critique of positivism: Ideology is not undone by correcting falsehoods, because it persists through form, secured through affect rather than reason.

John Latham is another artist who destroyed books – he burned, sawed or chewed them in violent symbolic acts that negated the authority of textual knowledge. Latham’s Skoob Tower ceremonies (1964–68) literally incinerated the Encyclopedia Britannica in pyres, happenings that carried fearful resonances in the post-Nazi period; [8] Still and Chew (1966) enlisted students to ingest and regurgitate pages of Clement Greenberg for Latham to bottle in acid. [9] These were iconoclastic gestures, treating the book as a sacred object to be destroyed. Unlike Latham’s negations of textual authority, Wiebe’s less violent process destroys books only to reassemble their material fragments – covers, titles, even their ashes – again, reflecting a culture where destruction rarely results in transformation. He recalls imagining the heat from a 2019 studio fire fusing his personal library into a single mass – an image that set him on the path to his book-based works. Study for a Water Burial (2024) made this logic literal: A rock salt urn containing ash from the fire was dissolved in an ultrasonic cleaner until the salt recrystallized across the machine’s surface, reforming even as it disappeared. Drawing on ecological burial practices in which these urns dissolve in the ocean, the work staged the same cycle: collapse that returns as survival, disappearance that insists on form.

Across his work, Wiebe draws on New Age and other artifacts referring to spiritual practices. His first collaboration with Final Hot Desert, then still in the Utah desert, [10] was Super Deep Healing Noise ✧ Sun Tunnels (120 Seconds) (2023), where he converted Mormon choral recordings into binaural beats – frequencies marketed to enhance concentration, relaxation, and even self-improvement – and played them through Nancy Holt’s solstice-aligned Sun Tunnels (1973–76). The work collapses the distinct forms of religious ritual, New Age healing, and Holt’s land art and its cosmic symbolism into a latent register based on their shared spiritual orientation.

Now housed in the London apartment of Benjamin Anderson and Marina Moro, Final Hot Desert frames the sculptures within a semi-domestic setting: Though the downstairs functions as a white cube, openings spill upstairs into the mezzanine bedroom. The book fragments that form Wiebe’s works retain visible traces of past readers – drawing a link back to when self-help was read, internalized, and quite literally taken to bed – before re-emerging as art commodities in the commercial gallery context. The result of the show is an impasse: Wiebe’s work endlessly recombines the structures of self-help rather than imagining collective alternatives. The sculptures show how even nonsense can remain legible as instruction. What emerges is less critique from outside than evidence from within: a view of a culture that cannot stop rebranding its failures as improvement.

“Graham Wiebe,” Final Hot Desert, London, June 28–September 13, 2025.

Sophie Barshall is a writer and editor from London. She is the founding editor of The Toe Rag magazine.

Image credit: Courtesy of Final Hot Desert, London

Notes

| [1] | Micki McGee, Self-Help, Inc.: Makeover Culture in American Life (Oxford University Press, 2005). |

| [2] | Eva Illouz, Saving the Modern Soul: Therapy, Emotions, and the Culture of Self-Help (University of California Press, 2008), 19.; and Leigh Eric Schmidt, Restless Souls: The Making of American Spirituality (University of California Press, 2005). |

| [3] | Kenneth Goldsmith, Uncreative Writing: Managing Language in the Digital Age (Columbia University Press, 2011), 24. |

| [4] | Don DeLillo, White Noise (Viking, 1985), 37. |

| [5] | Tim Griffin, “The Personal Effects of Seth Price,” Artforum 48, no. 10 (Summer 2010): 282–93. Griffin describes the book’s abrupt changes of register and contradictory advice as “false trails,” noting how its inconsistent voices prompt readers to sense a “phantom presence” behind the text. Disappearance, in this account, is less an act of erasure than a performance of shifting surfaces, where the seams of compilation become the very trace of what cannot be made to vanish. |

| [6] | Paige K. Bradley, “Band of Outsiders: Around New York,” Artforum, June 17, 2023. |

| [7] | New Models, episode 73, “Angelicism01’s Film01 w/ Lola Jusidman & Mateo Demarigny,” November 3, 2023. |

| [8] | Michael McNay, “John Latham: Radical and Inspirational Artist Who Courted Controversy and Pioneered Conceptual Art,” The Guardian, January 7, 2006. |

| [9] | John A. Walker, John Latham: The Incidental Person – His Art and Ideas (Middlesex University Press, 1994). |

| [10] | Exhibitions were site-specific and staged in remote locations, often a five- to seven-hour drive from the nearest city. Openings were rare; the works were mostly encountered online through documentation. |