ANNETTE WEISSER TO BRUCE HAINLEY Berlin, January 28, 2026

Annette Weisser, Berlin, 2025

Annette Weisser’s response to Bruce Hainley’s November letter was written in winterly Berlin, where she recently had a snow-induced “out-of-body experience in reverse” that makes Marcel Proust’s madeleine episode seem faint in comparison. Revisiting this moment in a still frozen but now slowly thawing city, Weisser speculates how an increasingly unambiguous image economy and our screen-based lives may affect memory formation. Following up on Hainley’s reflections on Catherine Breillat’s films (and her male protagonists in particular), she also addresses the director’s self-proclaimed inability to fully understand men, as well as Hainley’s incomprehension of what it is like to raise a teenage son – for Weisser, as a feminist, and today, in times of masculinist posers and politics. As she notes, the experience is puzzling and imbued with contradictions – something it has in common with Breillat’s films.

Dear Bruce,

It was a pleasure to share a meal with you and Anna shortly before Christmas. How strange to see you all wrapped up in winter garb, having known you almost exclusively in warmer realms! It’s still cold in Berlin, as it should be this time of year. Streetcar traffic has been suspended for the third consecutive day because of frozen overhead lines, and kids are making snow people from every bit of uncrushed snow. When it snowed for the first time this season, around New Year’s, I stormed outside, feeling free as a bird, like I did when I was a kid. I could tell from the happy faces all around me that I wasn’t the only one who felt transported. I underwent a sudden change of perspective and slipped inside myself; for a short moment, my perception fully connected to all my senses. Like an out-of-body experience in reverse, or the sensation of staring at a 3D-image and then suddenly “entering” it. By now, I’m familiar with this sensation. I can’t exactly say when I experienced it for the first time, but when it happens, it reminds me of what it feels like to be fully alive. It’s different from Marcel Proust’s madeleine moment insofar as being transported to my childhood is not the final destination; I don’t linger in the past but use those memories as a launch pad back to the immediate present. In fact, my most vivid embodied memories are from my teens and twenties. Perhaps it’s because at that age, I was simply wide open to the world around me. I suspect the real reason is that I came of age in the pre-digital era. Today, for 99 percent of my time, I live in a suspended state in which my brain does one thing and my body does – nothing, really. But apparently, the human brain isn’t wired to create emotionally charged memories from brain activity only. Does this mean I will gradually lose the capacity to form lasting memories?

Sometimes, my analogue yearnings make me watch movies from the ’70s or ’80s as the next best thing. I’m stunned by close-ups of sweaty faces in which the sweat doesn’t seem to “mean” anything in particular or by tracking shots along city streets where the houses look neither posh nor run-down, or those cute little cars that were just regular cars back then, entering and exiting the frame as they please. The abundance of visual information that doesn’t convey a clear message but is simply there without necessarily supporting the plot or character development is something that strikes me as distinctly different from contemporary mainstream productions, which are designed to be consumed by viewers whose attention is divided between multiple screens. A drive toward visual unambiguousness – or perhaps visual perfection that leaves nothing in the frame unevaluated – has taken over, and with it, the technically “enhanced” image. This, of course, has always been true in high-production-value movies. But now it’s seeping into every aspect of image production, down to amateur footage that circulates on social media. I’m sure legions of digital culture scholars have more poignant things to say about this, but I believe everyone should do their best to grasp the shifts in the media environment, and how it messes with our perception of reality, on every level.

A lot of what you wrote in your last letter resonates deeply with me. Coming to terms with the resurgence of grotesque hypermasculinity, inextricably linked to current crises, seems to emerge as one of the central themes of our exchange. Is Sean Penn’s Colonel Steven J. Lockjaw from Paul Thomas Anderson’s One Battle After Another modeled on Greg Bovino? And who the fuck is Bovino modeling himself on, Popeye posing as Reinhard Heydrich? [1] Everything becomes image, endlessly recycled, and these images work like yeast in the collective unconscious, combining this brand of fascism with other brands of fascism, incorporating half-forgotten movie scenes, blurring everything into this utterly unreal present. At first sight, the Gestapo-look appears to be a joke, an homage bordering parody. Yet as an image it triggers other, historically charged images that suggest a certain inevitability (you don’t mess with the Gestapo!) that finally translates into acts of performative violence in the streets of Minneapolis, Los Angeles, Portland, and so many other places where ICE agents are hunting down people, and those who aim to protect those people, with “absolute immunity.” Performative insofar as high visibility of ICE operations seems to be exactly the point, to scare protesters and squelch resistance, like in the early days of Nazi rule, when SA units unleashed extreme violence in German cities.

The use of the enhanced image in lieu of the unedited raw one is accelerated by the now widespread use of AI. Just a few hours after the killing of Alex Pretti in Minneapolis on January 24th, a “prettified” version of his professional portrait was circulated on social media by anti-ICE activists: the eyes a little wider apart, the gaze a little less piercing, the smile a little more pronounced, the hairline softened. More Jesus-y, I guess. Apparently, we all like our martyrs to look the part. (After 9/11, when Osama bin Laden’s image was everywhere on the news, my then 72-year-old aunt Anni exclaimed, “He looks like Jesus!”) I believe that the unwillingness to deal with ambiguous images (“good” people don’t always look good and vice versa) corresponds to an increasing unwillingness to deal with the ambiguous nature of reality in general. Just yesterday, Julia Klöckner, president of the Bundestag, during a speech on the Day of Remembrance for the Victims of National Socialism, chose to show an excerpt from a docudrama produced by the public broadcaster ARD on the Nuremberg trials to illustrate the horrors of the concentration camps. [2] Really? Docu-fiction? Wasn’t there any real documentary material available? Or perhaps she didn’t trust her fellow members of parliament to correctly identify the victims unless they look like Bambi and are accompanied by somber cello music. It’s deeply concerning when a high-level German representative endorses methods of historical misrepresentation not unlike those AI fakes that are flooding the web now with emotionally charged “snapshots” from the Holocaust. [3]

Since you brought it up in your last letter, I’d like to tell you a little bit about what it feels like to be the mother of a teenage boy. Like Catherine Breillat, I fundamentally don’t understand men, and raising one puzzles me. Parents get the children they deserve, which means, in my experience, children that challenge their own self-image. Voilà, I’m sharing my life with a meat-hungry, muscle-car-savvy, video-game-addicted, workout-obsessed mini-dude. Now deal with that, self-declared feminist! Every day, each of us is defending their territory. Quite literally: Whose piss is it on the bathroom floor? Seen from his perspective, my feminism must look rather simplistic: He relishes in pointing out male drivers of small electric cars versus female drivers of monster trucks. He says reading a book makes him fall asleep. I do love him a lot – a lot! – and watching him grow into his man-body is also a great pleasure. Yet it often pushes me to my limits. Like, do I have to condone misogynist language (inspired by the likes of Eminem – yes, he’s still popular in this age group!) from him and his friends in my own house that I would not tolerate in any other place? From the first time he playfully pointed a toy gun at me, when he was perhaps four years old, I was thrown into this conflict: I loathed him crossing over into that territory marked by phallic objects, yet I also want to give him all the freedom to figure out what kind of man he wants to become. (So far, no hints of queerness so fetishized among bohemian parents.)

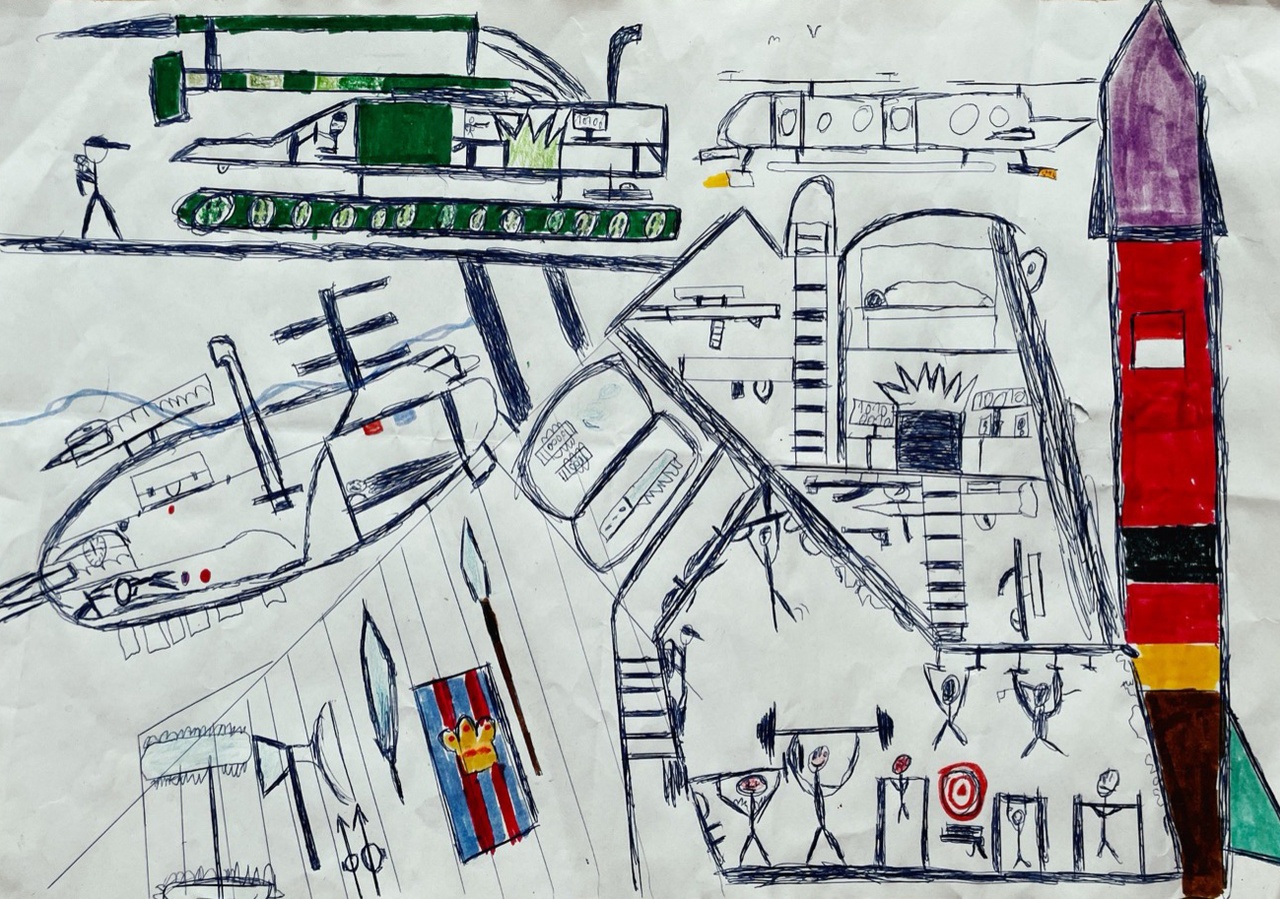

Luis Wilko Weisser, 2021

My son made a drawing of his “headquarters” when he was ten. After some half-assed admonishment regarding the sheer number of weapons in this otherwise brilliant work of art, he agreed to turn every blade into ice, coloring them light blue to render the composition “less dangerous.”

This week we watched the British TV series Adolescence (2025) together. The plot is every parent’s worst nightmare, which is certainly one of the reasons it got a lot of buzz when it came out last year. Episode three is centered on Jamie – the 13-year-old boy who has stabbed and killed Katie, a girl from his school – and the young female psychologist tasked with evaluating whether he has any understanding of the consequences of what he had done. During their conversation, Jamie goes through different emotions ranging from denial to rage, contrition, ostentation, and self-pity. At one point, he cites the “80/20 theory,” which he had picked up online. It postulates that 80 percent of men are attracted to only 20 percent of women, meaning there’s a fierce competition. The average guy can only “score” by either tricking the woman who is higher up on the attractiveness scale than he is, or by using violence. In their conversation, Jamie admits that he was attracted to Katie but got mocked by her. He doesn’t seem to have a recollection of the murder, instead he sees himself as one of her victims. In two instances, his desire to physically dominate the attractive young psychologist breaks through. She stays calm and presses him on his idea of what constitutes a man, and what male role models he grew up with. But at the end of their meeting, when she’s alone in the room, she loses her professional bearings for just a moment. Her face displays another range of emotions: compassion, disgust, and fear – a primordial fear many women have of men, regardless of their age. I tried to figure out what was going on behind my son’s own blank face: He obviously found it cringe to watch this with his mom. I sneaked in a couple of educational info-bites on Andrew Tate, delivered in the trembling voice of indignation, knowing all too well that he probably already knows more about him than I do. My son expressed sympathy for Jamie, because Katie was bullying him. He was under too much pressure, he said. What would you have done, I asked him. He looked away.

So, yes, men are appalling, and I say this as a menopausal woman and mother (not my only incarnations, either). As always, I turn to books for advice. In her 2004 book The Will to Change, bell hooks writes that it’s not men we must fight, but what she insistently calls “imperialist white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy.” She writes, “no man who does not actively choose to work to change and challenge patriarchy escapes its impact.” So in answer to your question, what it means to parent a son today, I’d say that I do my best to protect his capacity for love and self-love for as long as I can. How this translates into day-to-day parenting is a whole other story.

So long,

Annette

Annette Weisser is an author and artist. Recently she has taken up quilting to cope with existential anxiety.

Image credit: Annette and Luis Wilko Weisser

Notes

| [1] | Film critic Georg Seeßlen gives a brilliant close read of Bovino’s fashion choices: “Der eiskalte Menschenjäger,” Die Tageszeitung, January 28, 2026. |

| [2] | Carsten Gutschmidt, Nürnberg 45 – Im Angesicht des Bösen, Hessischer Rundfunk, ARD, 90 min., 2025. |

| [3] | Thomas Radlmaier, “Diese Postings entwerten die Arbeit von Gedenkstätten,” Die Süddeutsche Zeitung, January 14, 2026. |