CLOSED CIRCUITS Valerie Mindlin on “Coziness and Consciousness: Fragments of Artistic Life in Moscow in the 1990s” at the Museum of Moscow

Inspectorate of Medical Hermeneutics, “End of the USSR,” 2021

It’s easy to heroize the Russian Conceptual art of the Communist years. Sequestered behind the Iron Curtain and censored into precarity, it is almost as if the usual judgment criteria don’t fully apply to that generation of artists; their precipitous transgression and discontinuity from the Western theoretical discourse constitute a protective shield of presumed artistic purity. Said ignorance and separation were, of course, neither total nor complete, even in the darkest years, but they did indeed structure the creative parameters of that artistic landscape. Under the conditions in which the only available parameter for self-identification as a proper professional artist was membership in the Artists’ Union of the USSR, which was Party-sanctioned and Social Realist, functioning as a de facto guild system akin to those of the Middle Ages, or, in Boris Groys’s insightful description of how the group “reminds one of the celestial hierarchies described by Giorgio Agamben: totally defunctionalized, their remaining activity is reduced to singing Gloria,” [1] the question at the heart of all early Moscow Conceptualist practice was that of identity, of querying, and trying to answer the question, “Who is an artist?” However, with the fall of the Soviet regime and the onset of the new conditions of the post-putsch years, including a nascent art market and a functional creative ecosystem, the generation of artists whose work dominated the 1990s Russian art scene shifted from a concern with self-avowal to questions of reception and hermeneutics. That later generation’s practices are the focus of the Museum of Moscow’s “Coziness and Consciousness: Fragments of Artistic Life in Moscow in the 1990s” (Uyut I razum).

The exhibition takes its title from the eponymous 1994 text by Pavel Pepperstein, a meditation on the peculiarity and power of the Russian language somewhat akin to Georges Bataille’s Critical Dictionary of abstract definitions and metaphysical concepts (a fitting semblance given Pepperstein’s Surrealist affinities and Nietzschean disposition). Aside from the Pepperstein-founded Inspectorate of Medical Hermeneutics, the show also collects the output of FenSo (an acronym for Fenomen Soznaniya, or the Phenomenon of Consciousness), Russia, TaRTu (Taina Rady Tainy, or Mystery for the Sake of Mystery – the group’s motto), Cloud Commission, and Fourth Height. The taxonomy, however, is largely loose, with groups interchanging and cross-pollinating members, assembling and dissolving, and toying around with authorship models throughout. The curators’ conceit here proposes to repurpose the title itself into a designation for the two semi-autonomous zones of the show – the physical and the archival. Yet the archival as an impulse pervades overall, in the work just as much as in the dedicated gallery of assorted zines, press releases, posters, and photographs of the era.

“Coziness and Consciousness,” Museum of Moscow, 2021, installation view

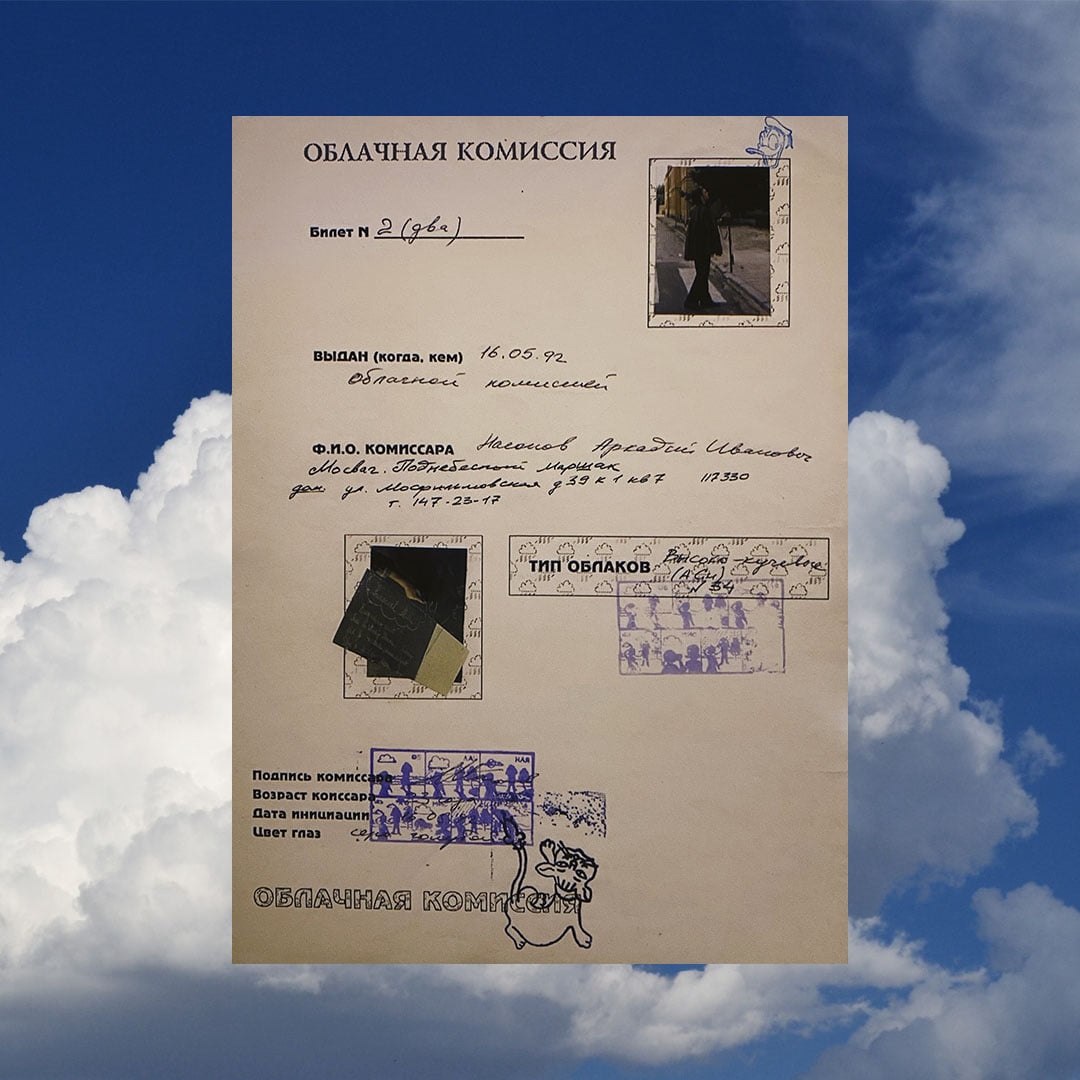

The exhibition focuses on collectives. In Moscow, in the 1990s, that specific modality of practices reveled and indulged in discursivity and the space freshly stripped of ideology, investing anew in the self-mythologizing ethos of secret societies. Throughout most of these artists’ lives prior to the 1990s, sociality – the conception of the Soviet state as an “inflated community,” as Ilya Kabakov reflected on his pre-perestroika experience a few years later – “was a means of survival, the traditional Russian commune that later also entered Soviet reality, in which you as a volunteer or subordinated participant were forever drowned, dissolved.” [2] While carving out smaller, private communities from that earlier reality provided a limited escape from the overwhelming anonymity at the time, for younger artists later on it became a means of exorcising the traumatic shadow of the shameful collectivized past; they utilized the bureaucratic operating procedure as a medium of work in itself. In this way, the Heideggerian postulate of art’s charge to become a technology that brings the remnants of the past into the present becomes acute in a very historically specific way. Thus, the exhaustive archiving and redundant methodization of the groups’ inside rules and rituals – presented in the show with the ubiquitously displayed reproductions of the Cloud Commission membership cards, designed to imitate the pervasive over-institutionalization of the old world in a transparent imitation of the Communist party tickets – as well as the meticulous documentation of inner rituals and discussions by TaRTu and FenSo, constitute artworks in themselves. The aesthetics of administration of the Moscow Conceptualists in the 1990s held a decisively different, historically cathartic import compared to that of their Western cohorts.

Cloud Commission, “Membership card, Arkady Nasonov,” 1992

The Cloud Commission was founded by Arkady Nasonov and Dmitry Ligeiros in 1993 and quickly became the largest Russian art collective of the 1990s, counting over 1,500 artists among its members. The collective took its name from the Cloud Commission of the General Geophysical Observatory and was inspired by the Commission’s 1930 book A Guide to Determining Cloud Forms. Borrowing a methodology of its scientific namesake, the group invited each member to select their favorite cloud type and officially become its observer. One of the co-founders, Oksana Sarkisyan, wrote that the Cloud Commission “symbolically erects a distance in relation to the Soviet experience, sets up a perspective for its observation, and organizes a scientific approach and work toward collection of its ethnographic material for laboratory studies.” [3] Instructively, she describes Nasonov as a figure of the heroic scientist, his ideas as a return to the original Soviet utopia of scientific experimentation, and his art as “conservation of mental space.” Nasonov’s Albom v ssylku (Album for reference, 1996) is exemplary of the nature of practice that dominated the landscape of 1990s Moscow. Headlined by Cyrillic epigraphs such as “After Democritus,” “After Baudrillard,” “After Barthes,” et al., in a roll call of the dominant figures of the time’s trendy theory, this series of collages subtly tweaks old Soviet slogans and imagery into illustrative apothegms for their titular theoretical tie-ins. In this way, in Po Derrida (Based on Derrida, 1996), for example, an old agitprop image of Soviet agronomists is crowned by a calligraphic quotation:

You will scatter the meaning across the white lightThe roots of the signs are risingAnd the dough will become KolobokOn the last day of Man’s summer [4]

Here as elsewhere in the art of the decade, the question of truth versus meaning becomes central, coming to replace the preceding existential malaise of self-affirmation. The aforementioned Kolobok, an iconic Slavic folktale character, is a ubiquitous presence in the show as well. Like a non-anthropomorphic gingerbread man, Kolobok is an unbaked ball of dough that rolls off an couple’s kitchen table and goes out into the world to pursue adventures. The blank spherical malleability of this character was a source of constant fascination for Pavel Pepperstein and the Inspectorate of Medical Hermeneutics especially, taking on endless modalities and guises in a slew of their gnomic drawings throughout the 1990s: an “oneiroid” state, an unfinished scepter, a nimbus, an “attribute” – the Inspectorate’s half-sensical hand-drawn vignettes delighting in the complete collapse of meaning and in the calligraphic physicality of mark-making. The Inspectorate’s most emblematic work of the period parodically exacerbated the deconstructive impulse of the era into absurdity, and Kolobok’s infinitely inflectable ludicrousness presented an ideal medium for such exercises. It has also served as an element in many of the collective’s installations, one of which was re-created for the present show.

Arkady Nasonov, “Albom v ssylku (Album for reference),” 1996

In the End of the USSR (2021), the Inspectorate imagine a new version of the erstwhile Union’s state emblems: surrounded by a nimbus of a wheat wreath, the traditional rising sun is here replaced by a drab Soviet table lamp. Instead of the globe crowned by hammer and sickle, the perfectly spherical, white shape of a sleeping Kolobok now hangs suspended in an improvised hammock – a forever-ambiguous dormancy for the new state of the wide-open world’s hermeneutic morass so readily embraced by this generation’s artists.

One walks away with a sense of having walked in on a meeting of a cool kids’ secret club, neither invited nor rejected, but simply too late to the party. So evolved, self-contained, and discursively insular was the decade’s art, its need for an audience seems to have been largely perfunctory, and proudly so.

As in Kafka’s famous aphorism, what seems to best characterize the generation of Moscow Conceptual art in the 1990s is the feeling and knowledge of sheer joy and indulgence of “understanding that the ground you stand on cannot be any bigger than the space your two feet can cover.” [5] And after so many years of struggle, it is hard to begrudge that.

“Coziness and Consciousness: Fragments of Artistic Life in Moscow in the 1990s,” Museum of Moscow, April 29–July 4, 2021

Valerie Mindlin is an art historian currently based in Moscow.

Image credit: 1 & 4 – courtesy of the author; 2 & 3 courtesy of the Museum of Moscow

Notes

| [1] | Boris Groys, History Becomes Form: Moscow Conceptualism (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2013), 13. |

| [2] | Ilya Kabakov, The Text as the Basis for Visual Expression, ed. Zdenek Felix (Cologne: Oktagon, 2000), 360. |

| [3] | Quoted in exhibition booklet. |

| [4] | My translation. |

| [5] | Franz Kafka, A Hunger Artist and Other Stories, trans. Joyce Crick (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 190. |