WHEN IRONY ATTEMPTS FORM Cecilia Bien on Steirischer Herbst 2025, Graz

Manuel Pelmuș und Frédéric Gies, “Tribute to Kurt Jooss’s ‘Green Table,’” 2025, in “Nie Wieder Friede,” Steirischer Herbst, Graz, 2025

For this autumn’s edition, Steirischer Herbst draws its title from the 1936 play Nie wieder Friede (Never Again Peace) by Ernst Toller, in which a nebulous war is declared as a farce during a peace festival in the fictional pacifist republic of Dunkelstein. Citizens promptly arm themselves, and peace songs immediately shape-shift into war cries. The reactionary response exemplified in the play exposes both the performativity of peace and the volatility of human behavior, above all in times of changing political ideologies. For an art festival to take up this indictment by antiwar activist Toller, who intended the play as a satire directed at a complacent Europe as it fell to fascism, is not only to aestheticize a similar moment of our present but also to suture the gap between a local public’s historical memory and an international art audience’s interpretation. To negotiate this relationship, the curatorial maneuver is often to cloak itself in the language of contemporary art, legible only to those familiar with its coinages and opaque to the rest. Steirischer Herbst resists this default, however, by alternatively exploiting the irony of the well-known slogan Nie wieder Krieg of the interwar years through its apparent inverse, Nie wieder Friede.

Aesthetics of groupthink were addressed on opening night with what was framed as a public intervention choreographed by the artist group LIGNA. Admission to the event required a ticket for access and to reserve headphones, which, once procured and put on, played a voice instructing actions such as walking toward the statue of Franz I in Freiheitsplatz, and then to stop, in unison. We are told to dance, then to raise an arm in salutation, and then to make eye contact with a stranger across the square. Before anyone knows it, we are part of a simulation reenacting the gestures of times when fascism reigned. Without hesitation, the majority of the audience obeys with enthusiasm and without deviation. If LIGNA’s point is precisely to make visible our proclivities toward conformity en masse, perhaps they’ve succeeded in proving how quickly we find ourselves as unthinking subjects taking orders. Our tacit commitment to the public intervention reveals that it can only take its artistic form within the rigors of a united submission, as long as everyone knows how to behave. And we do know how to behave– as proven through our inadvertent collaboration, in which we contribute at once to the work’s content while enabling its formal realization.

LIGNA, 2025, in “Nie Wieder Friede,” Steirischer Herbst, Graz, 2025

For the festival, Freiheitsplatz has been renamed Freiheitsplatz for the third time. Instead of commemorating the 1918 collapse of the Hapsburg monarchy and start of the Austrian Republic, or the 1938 Anschluss proclaimed by the Nazis, in 2025 it is for the festival, by Ahmet Öğüt. During a ceremony in late June, the artist rechristened the square Freiheitsplatz in the presence of a lawyer. In Öğüt’s speech, he explicated the co-optation of the word “freedom” by far-right nationalist and populist parties historically and in the present day. Although Öğüt asserted his ambition to liberate the term by way of this statutory procedure, his reclaiming of “freedom” to detach it from the square’s fascistic roots unfortunately conjures the futile rhetoric of Nie wieder Krieg. Öğüt’s renaming also recalls Hans Haacke’s reconstruction of an overbearing column tagged with swastikas and the imperial eagle for the 1988 festival Schuld und Unschuld der Kunst (Guilt and Innocence of Art). Haacke had covered the column with the total numbers of minorities who died or were killed in Styria during the Nazi regime. The local press reacted relentlessly during the artwork’s installation, prompting protests in the region and, before the end of the festival, an arsonist attack. Yet, Öğüt’s legal renaming before this year’s festival holds no candle to the incisive and aggressive attitude of Haacke’s public installation of ’88. Rather, it couches its criticism in a grand narrative that, in the end, merely hovers between pseudopolitics and sarcasm.

During her opening speech, festival director Ekaterina Degot remarks that freedom is the same thing as unfreedom, ostensibly using this false equivalence as a provocation to interrogate how the slogan of the interwar years, Nie wieder Krieg, can just as quickly turn to Nie wieder Friede in Toller’s play. Steirischer Herbst’s founding in 1968, according to Degot, intended to redirect global political eruptions into the safer territory of art. Politics could then move from violent regimes to sites of discursivity by being outsourced to the arena of art, where confrontation could be abstracted or simply avoided. The acknowledgement by Degot that art can in no way save the world might also imply that the posturing of art as an exceptional site for freedom and self-expression is merely an illusion, especially if their meanings are as fickle as the political rebranding of cliches. In reading Degot’s statement as something of a disclaimer, one has to ask where the faith in art is, and how circumventing responsibility is a valid approach under the banner of a festival concept with such consequential political weight.

“Six Characters of Hotel W.,” 2025, in “Nie Wieder Friede,” Steirischer Herbst, Graz, 2025

Later that evening, performers continue to evoke the Nie wieder Friede theme at Helmut List Hall. Two performances engage satire to attend to the theme’s ambition with certified measures of crowd-pleasing. In Tribute to Kurt Jooss’s “Green Table” (2025), dancer Frédéric Gies starts out as a mime in a suit, and after several swift costume changes performed right under the spotlight, he prances across the stage in only white trousers, dramatically waving a white flag. He regales the audience by gesturing toward his nether regions, and everyone laughs in good spirits, as they had during LIGNA’s intervention, when the narrating voice remarked on prostitutes who would frequent the theater in search of clientele. Laughter can be medicine, but this kind verges into the territory of being canned. An aesthetics of reception appears to be strategically deployed by the performers, reminding us not to take them or ourselves too seriously. It is, after all, art and not war. The next performer is Ivo Dimchev with Hot Sotz (2025). Aware of the redundancy in conflating moralistic politics with radicality, he iterates more than once, “I was asked to be more political,” as he shakes his zany fluorescent hairpiece before starting a chant to normalize sucking. Then, in an attempt to change the stale tone to one of rabble-rousing, Dimchev demands, “Who masturbated before the show?” turning no one on. But the audience, ever so obedient, remains eager to demonstrate their liberated position – when Dimchev asks if we want dirty songs or love songs, everyone shouts in resounding chorus, “Dirty!”

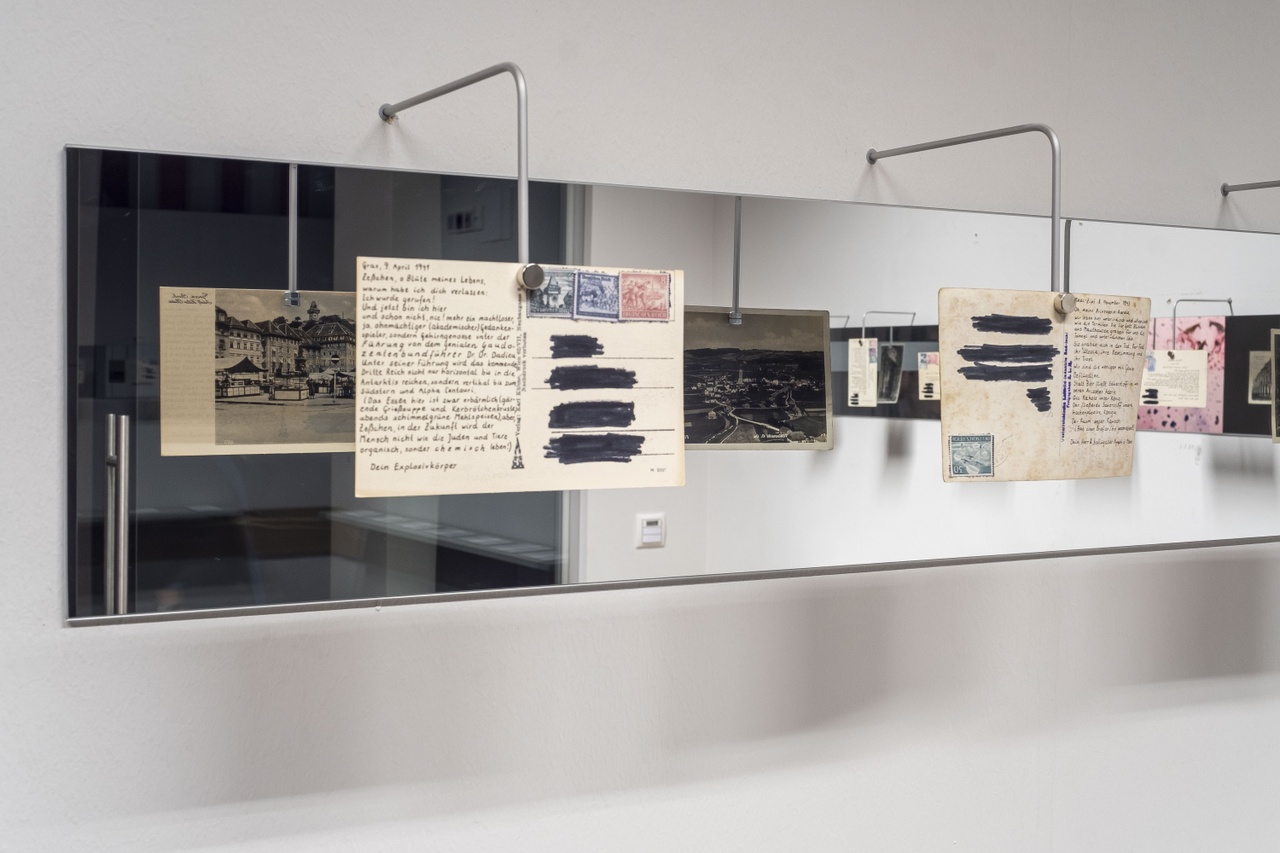

The main exhibition, which opened to the public the next day, is set inside a now-vacant distillery in Graz’s Gries district. For the duration of the festival, the space has been renamed BAU, a word that can be translated to anything from “construction” to “den” to “prison,” reflecting provisional purposes from banal to loaded contexts. Throughout the BAU, a curatorial intervention, Six Characters of Hotel W., commissioned to six writers, makes use of the postindustrial interior as a backdrop for found vintage objects and conjured letters stained by a vague patina. These props are used to tell stories in exacting detail of six different individuals who revolved around the imaginary Graz grand hotel, housed in the BAU, which, per the writers, functioned as a key transit zone in 1945 during the end of the Second World War. Among the characters are an acclaimed diarist in charge of denazification, a Surrealist turned partisan, and a young dancer turned Communist. Without the copious amounts of reading required to get the gist of these stories, the intervention can at first be understood as an exercise in set design. However, it makes the successful transformation to art not through commodifying a loaded topic, but through lucid historical accounts beyond the comfort zone of satire. Moral dislocations and human contradictions inextricably bound to everyday life during the war are exposed. The diarist, for example, contemplates an “art of selective justice” as a practical approach to denazification – persecuting some but not others according to his own coded logic. He rationalizes that when everyone is responsible, no one is. The stories cleverly weave together an underlying message: Where one stands in the mind’s eye is not always the same in the moment when one must choose sides as in hindsight, when one tells themselves that they were on the correct side of history.

Mounira Al Solh, “Stray Salt,” 2025, in “Nie Wieder Friede,” Steirischer Herbst, Graz, 2025

The curatorial task of translating between local experiences during past war periods while addressing current global atrocities is executed with a self-awareness for negotiating conflicting versions of the past. With the many newly commissioned works iterating these versions, however, an incongruous response to the festival theme is inevitable. While the curators are explicit in their solidarity with Palestine, a rarely proclaimed position within the institutionalized art worlds of Germany and Austria, two works referencing the war in Gaza take a pro-Palestinian stance without the slightest provocation or use of themselves as conduits for disseminating otherwise prohibited criticism of the state. Candice Breitz, whose exhibition at Saarland Museum’s Modern Gallery was cancelled last year because of her public statements on violence in Gaza, and who has since experienced increased visibility, has updated her work criticizing ripple effects of apartheid to address genocide in our present. In Dear Esther (2025), drones capture the work of choreographers spelling out “Racism,” “Fascism,” “Palestine,” “Israel,” and “Never Again” with watermelons, interrupted by footage of Breitz learning “Bel Ami” on the accordion with Esther Bejarano, an Auschwitz survivor who later became an outspoken critic of Israel. Stephan Mörsch, known for his wooden models at 1:10 scale, takes his craft to the Gaza Surf Club (2025) to challenge the condescending gaze on Gaza as, per the wall text, an “open air concentration camp,” through miniature displays of surfside lodges on stilts. For these works commissioned specifically for the festival with no reliance on the market, one has to wonder why so little formal risk is taken.

Two animations from the main exhibition reference wars experienced by artists in their respective countries of origin; they also successfully avoid the all-too-familiar projection of alterity that insists on a work’s significance via the artist’s biography. Mounira Al Solh’s multi-channel videos in Stray Salt (2025) feature animations illustrating the endless cycle of war by connecting the artist’s recent memory of the Lebanese Civil War with several historical examples of Phoenician resistance against attempts at annexation. Dana Kavelina’s stop-motion animation Grey Earth (work in progress, 2025) follows vignettes through a barren Ukrainian landscape. A soldier, lost or defected, keeps himself company by recalling adages from his grandmother in a faint, drifting voice. He reflects up to the half moon, and then to a beetle feebly rolling a ball of dirt in the infertile ground: “They rented my body and now I have to pay back the debt.” Meanwhile, a lonely cow wanders, unable to feed off the now-inedible crops that have been sprayed by drones. Without seduction or outrage, Grey Earth touches upon the anguish and sweetness of minor stories alienated by the structures they serve. There is no making of heroes here, just simple lives finding ways to keep going. This sober and tender but also blank expression is one of the most artistically astute responses to the theme of Nie wieder Friede.

For the small city of Graz, longitudinally aligned with Eastern Europe yet which has historically identified as part of the West, reconciling East versus West meanings of freedom from the mid-’60s would mean finding a politics between those seeking freedom from state-imposed ideologies and those seeking freedom from the society of the spectacle. Fast-forward to 2025, and attempting a unified meaning of freedom further reveals that all realities are fragmented. The impossibility of translating disparate subjective experiences with war and peace, between local and global contexts, has surrendered to an all-encompassing theme with end-of-history irony. At the same time, the festival contends with its role as a source of local pride for liberal middle-class taxpayers who identify residence in their city with Steirischer Herbst, and presumably with its recent satirizing of left-ish politics as well. With a main exhibition held in a migrant-majority working-class neighborhood, where only 15 percent are eligible to vote, and with a regional politics that hasrecently swung to the right, turning both local and global politics into what looks, feels, and smells like art is a big ask, or simply a sign of gentrification. Yet for all the diluted artistic responses, the curatorial self-reflexivity of this year’s festival prompts a glimpse into the future, in which looking back at our current moment with tenderness or with remorse may be one and the same. If this is the case, perhaps it is only within our own interiorities, with full and honest disclosure, that we may begin to align our instrumentalizations of memory with how we wish to be in the present.

“Nie wieder Friede,” Steirischer Herbst, Graz, September 18–October 12, 2025.

Cecilia Bien is a writer based in Vienna and New York.

Image credits: 1. Photo Dajana Lothert; 2. © Steirischer Herbst, Photo Johanna Lamprecht; 3. © Steirischer Herbst, Photo Mathias Völzke; 4. © Steirischer Herbst, Courtesy of the artist, Photo Mathias Völzke