Electroconvulsive Lit John Kelsey on Sylvère Lotringer’s “Mad Like Artaud”

In the early 1980s, Artaudian delirium seemed the perfect lens for viewing and processing postwar “control society” and post-recession New York City in particular. Sylvère Lotringer, teaching French literature while publishing Semiotext(e) from his office at Columbia University, was a channel for this even as Artaud’s influence was already pervasive in downtown culture, from the Living Theater to Kathy Acker, from “transgressive” literature and performance to underground cinema, No Wave, and noise music. A “hidden Jew” (says Lotringer) writing under psychiatric confinement in occupied France, Antonin Artaud and his wild late thought informed Semiotext(e)’s “schizoanalytic” resistance to neoliberal capitalism at a time when traditional critique seemed less effective than a perverse multiplying of connections while decoding capitalist desire on the fly. There was also an impulse to unleash literature as a biopolitical weapon, which implied deploying language at the level of the queer, desiring body and in direct relation to lived, urban space, within and against gentrification and professionalization. Displacing “literature” between the salon and the asylum and refusing to let it settle in either place, “Mad Like Artaud” – which started as a series of interviews by Lotringer that he later expanded by adding essay-like sections through the mid-2000s, years after leaving New York [1] – has a nomadic and piecemeal history: it’s not just a book but a life project that spans decades, languages, and contexts – picked up, dropped, and returned to again and again, before and after the Internet. This extended process also allows the author to reencounter himself as a figure in time, to recognize and replay Lotringer as fiction, even.

A literary biography of Artaud could be split into two main sections: before and after electro- shock. Its first half (1896–1937) would comprise most of the poet’s actual life: his years among the Surrealists in Paris, his acting career and failed attempts to realize his “Theater of Cruelty,” then a pilgrimage to the Tarahumara Indians in Mexico, after which the poet’s religious obsessionality and paraphrenic delirium began to take over, leading to his arrest aboard a ship for causing a public disturbance with a magical stick. The post-electroshock years (1943–1948), meanwhile, would include most of Artaud’s writing and all of his drawings, his sudden return to fame as a poète maudit among a new postwar generation of Parisian literati, but only a few short years of life, ending with a drug overdose. But “Mad Like Artaud” is no literary biography. It starts with the missing years of Artaud’s incarceration within various mental institutions, where he suffered concentration camp-like conditions under the Vichy regime. Lotringer, traveling from post-punk New York to rural France to interview Artaud’s former doctors in 1983, spins a sort of schizoanalytic docufiction around a literary controversy, heading upriver “Heart of Darkness”-like, picking up the threads of Artaud’s delirium among all those it touched and aiming straight at the event of electroshock itself: was it crucifixion or cure, for Artaud? Lotringer doesn’t need to answer this question; what counts, for him, is to raise it in the most unsettling way possible, as a means of gaining passage through the eye of what is referred to as the “Artaud Affair,” where literature and delirium flow as if from the same source.

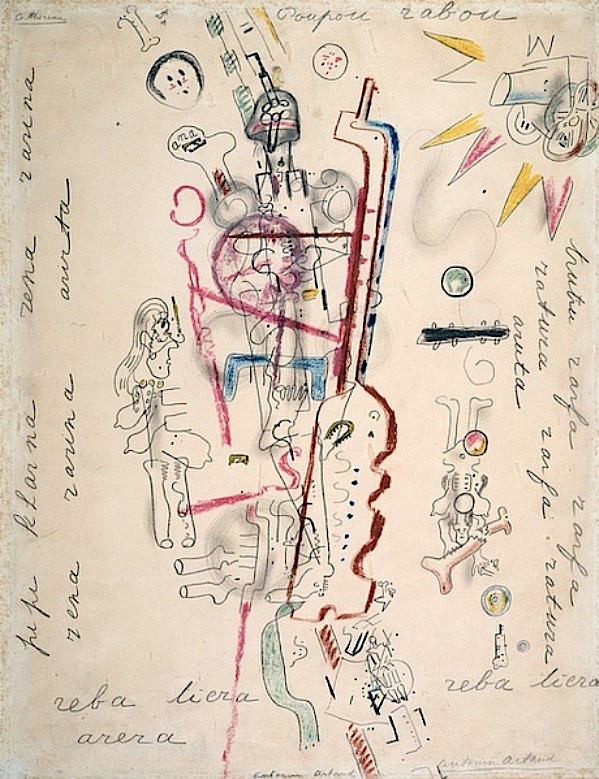

Antonin Artaud, “Poupou rabou,” 1945

Antonin Artaud, “Poupou rabou,” 1945

In “Mad Like Artaud,” we learn that Dr. Gaston Ferdière, the man who administered the shock treatments at Rodez, was himself a minor Surrealist poet who would later be accused of jealously punishing his patient’s genius. So from a certain angle, electroshock becomes another experimental means of communication between modern poets, involving induced comas, intermittent loss of self, and a fractured spine for Artaud. Reading Artaud’s precise and harrowing descriptions of how the treatments affected his being, or loss thereof, in texts like “Electroshock (Fragments),” and then his indictment of psychiatry as social control in “Van Gogh: The Man Suicided By Society,” it’s no wonder he was martyred in the eyes of his fans, becoming a poster boy for the anti-psychiatry movement in the decades following his death. But Lotringer deviously reminds us that this “man of letters” was also an actor and a skilled manipulator of situations (maybe even a “robot” and a “conman,” to echo Lotringer’s diabolical appropriation of L.-F. Céline’s anti-Semitic rhetoric), [2] and that mythmaking always goes hand in hand with psychosis. The paradox here is that none of Artaud’s blazing attacks on psychiatric control would have been possible without electroconvulsive therapy, because evidence suggests that it was only thanks to these experimental blasts to his brain that the poet avoided remaining a despondent, unproductive ghost, or becoming “asylum rot,” as they called patients in the days before softer pharmaceutical cures. However violently and lucidly Artaud opposed and resisted it, electroshock had become part of his poetic process (just as his “Letters from Rodez” now belong to the official history of electroshock). Lotringer even suggests that Artaud was somehow destined for electroshock, having already invented it himself in texts such as “The Theater and the Plague.”

“Plague” is a word that recurs throughout this book, describing how delirium exceeds the private individual, moving through the real world as it makes connections and populates itself with whomever it’s able to touch. And Artaud of course touched many people: as an actor, as a poet, as a patient and friend, and then increasingly and unstoppably, after his death, as myth. “Mad Like Artaud” traces his schizophrenia throughout the literary and psychiatric contexts he contaminated and beyond (Jesus, Hitler, Satan, Coleridge, and the Dalai Lama are all implicated too), leaving full-blown dramas everywhere in his wake. Tel Quel intellectuals and Lettrists accuse his “mad” “Nazi” doctors of abuses on the scale of Guantanamo Bay. The doctors accuse Artaud’s family of letting him starve during the war, while the family accuses drug-dealing Artaud clones of ransacking his room for papers after offing him with opium. Dr. Ferdière fingers Paule Thévenin, who dedicated her life to editing the poet’s “Œuvres Complètes,” accusing her of forging certain texts to advance her own career. And then there’s Ferdière’s former intern Dr. Jacques Latrémolière, forever resentful that nobody (until now) ever asked for his side of the story, insisting that Artaud was just a sexually impotent hack and a bad Christian. Many of these dramas were still hot to the touch when Lotringer conducted his interviews between 1983 and 1985, but he prefers not to take sides, being always more interested in how delirium functions as a process that “breaks down the wall of the signifier” while “making a shambles of psychiatry” and the literary establishment both. [3]

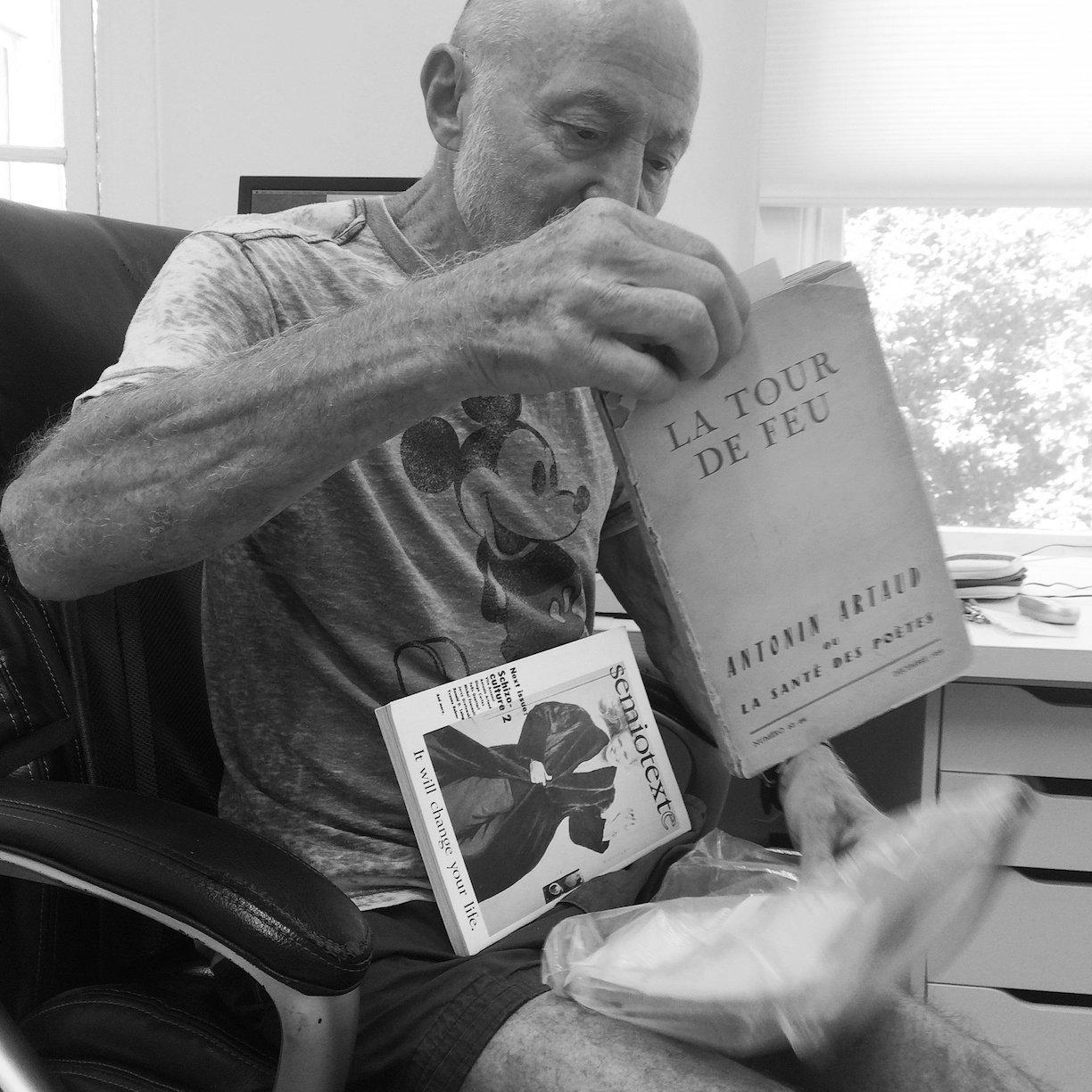

Sylvère Lotringer, Los Angeles, 2015. Photo: Jonathan Thomas

Sylvère Lotringer, Los Angeles, 2015. Photo: Jonathan Thomas

In his exchanges with Dr. Ferdière and other key players in the Artaud Affair, Lotringer brings a perverse intelligence that gets under the skin and draws libidinal energies to the surface. He may be a bit of a robot and a conman himself as he plays these people off against each other, digging up so much French dirt with his tape recorder on. This book feels closer to reality television than to an academic study, and for this reason actually gains better access to its subject than your typical literary biography would. As a way of having done with the ridiculous and ongoing controversy in France surrounding the question of Artaud’s Christianity or atheism, “Mad Like Artaud” begins with a provocation: Lotringer constructs a madcap argument that Artaud’s over- the-top Christianity was a performance typical of Jews in hiding under the Vichy regime, and that Artaud was therefore a Jew. Bringing his own biography and some East Village schlock tactics into the picture, Lotringer upsets the academic script that always tends to romanticize the poet’s solitary madness while simultaneously cornering him in a neurotic “safe space” notion of literature. He insists that Artaud’s delirium was in fact a means of opening himself (and literature) to the madness of the times he was living through, even if he did spend the entire war in a straightjacket. He also reminds us that the author of “All Writing Is Pig Shit” was never not operating with a supremely devastating sense of humor.

2015 seems like a good moment, again, for Artaud, as the American poetry scene finds itself in such a state of crisis, accusing itself of rape and racism, with poets mobbing and life-ruining each other repeatedly via social media, issuing death threats even, while at the same time demanding more and more political correctness and self- policing within its own practice. It’s been a truly delirious year for poetry, as it suddenly rejects the postmodern, vanilla fate of coolly “moving information” back and forth between contexts and platforms (as poet Kenneth Goldsmith has described his own work). [4] Interestingly, the more poetry gravitates to social media and the Internet – both as means of distribution and an idea of what poetry is or could be today – the more these very platforms become the site of the poetry world’s implosion. There’s nothing cool about it now, but in the current PTSD-inflected culture of campus life and beyond, poetry still sometimes betrays a nostalgic longing for a “safe space” separated off from the market and its violence. In “Mad Like Artaud,” André Breton comes off as lamely allergic to any Surrealism that transgressed his normcore taste for the “marvelous.” Isidore Isou, on the other hand, was such an Artaud wannabe that he practically begged Dr. Ferdière to electrocute him too, stalking the beleaguered doctor at all hours of the night. And how should literature act nowadays, online and in life? Increasingly, it’s become a political as well as a technical question. Poetry is no longer imagined as a sort of “correlationist” virus eating its way through bodies and minds (without trigger warnings), taking on a life of its own, rampant, biblical, cosmic. We have apps for that now. But if it did not die under electroshock at Rodez, it seems doubtful that poetry will end today in a safe space, policing identities and dosed on antidepressants.

Sylvère Lotringer, Mad Like Artaud, Minneapolis: Univocal Publishing, 2015.

Title image: Antonin Artaud at Rodez, ca. 1946

Notes

| [1] | The interviews were first published as “Ich habe mit Antonin Artaud über Gott gesprochen,” Berlin 2001. An updated version was published in France as “Fous d’Artaud,” Paris 2003, and then in Italy as “Pazzi di Artaud”, Milan 2006. Note: the two essays in Part II (pp. 31–64) and Part III (pp. 129–143) of “Mad Like Artaud” were written in English and appear for the first time in this edition. |

| [2] | Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Bagatelles pour un massacre, Paris 1937. |

| [3] | Gilles Deleuze/Félix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus, Minneapolis 1983, p. 135. |

| [4] | See: Alec Wilkinson, “Something Borrowed,” in: The New Yorker, 5, 2015. After appropriating Michael Brown’s autopsy report as “found poetry,” Kenneth Goldsmith has found himself at the center of recent controversies around the racism of “conceptual poetry” in America. Wilkinson’s New Yorker article on Goldsmith and the controversy has also been slammed as racist. See Cathy Park Hong, “There’s a New Movement in American Poetry and It’s Not Kenneth Goldsmith,” http://www.newrepublic. com/article/122985/new-movement-american-poetry-not- kenneth-goldsmith; and Brian Kim Stefan, “Open Letter to the New Yorker,” http://www.arras.net/fscIII/?p=2467. A similar controversy erupted around the poet Vanessa Place. See Natasha Stagg, “Vanessa DisPlaced: Racism vs. Censorship,” http://dismagazine.com/discussion/77245/ vanessa-displaced-racism-vs-censorship/. Meanwhile, a network of “literary activists” known as The Mongrel Coalition Against Gringpo has been very active on social media: http://gringpo.com and https://twitter.com/ againstgringpo. A recent article on “literary activism”: http://www.poetryfoundation.org/harriet/2015/08/ responding-to-what-is-literary-activism/ |