Malerei malgré tout Maria Muhle on "Painting 2.0" at Museum Brandhorst, Munich

Material, gesture, network: in the following text, Maria Muhle, reviewing this exhibition, finds painting’s points of inclusion suspended between autonomy and commodified imagery, between the painting’s body and bodily paintings, asking, in turn, what position might painting now claim in between material space and the net?

With more than 230 works by 107 artists, the exhibition “Painting 2.0: Expression in the Information Age” fills all three gallery floors of Munich’s Museum Brandhorst. Arranged in loosely chronological fashion, the show traces an arc from the discussions over the end, death, or obsolescence of painting in the 1960s to today’s debates regarding digital and post-digital art to reconstruct the more recent history of painting, including the disruptions it has suffered and the sudden turns it has taken in response to competitive pressures and challenges from other, “newer” media, both analog and digital. Interestingly, the curators have divided the show into three thematically focused sections – “Gesture and Spectacle,” the medium of “Eccentric Figuration,” and the field of “Social Networks” – one per floor, to limn this history with each segment telling its tale in parallel to the others. The purpose is to present a kind of painting that negotiates the discussions over its demise within its own medium. And so, the visitor encounters mostly just that: painting, in the basic sense of paint applied to a canvas.

The battle lines are drawn in what is staged as the exhibition’s “primal scene”: on the one side, there is the discourse of the end of painting, which its proponents conceive as the critique and destruction of modernist – in Greenbergian terms: medium-specific, autonomous, self-contained – painting as the record of the artist-subject’s unconstrained, expressive, abstract gestures on the canvas; meanwhile, the society of the spectacle, in which all visual production is always already commodified, effectively opens a second front against painting’s autonomy. Since the 1960s, that is the hypothesis the exhibition lays out, painting has thus been boxed in between the poles of “gesture” and “spectacle,” buffeted by contrarian forces as it has sought to strike a balance between the radical autonomy of high modernism and the absolute heteronomy of the world of commercial imagery.

On the museum’s ground floor, an ensemble of “mediated gestures” outlines this primal scene as the exhibition’s matrix: pictures by Piero Manzoni and Yves Klein – who tend to take a parodic approach to the critique of modernist painting’s creative gesture – as well as Niki de Saint Phalle, whose “Tir” proposes a firing squad that, in finishing painting off, at once unleashes a fresh distribution of paint across surfaces. Across the room, the very deluge of images Guy Debord denounces in “The Society of the Spectacle” figures as the point of departure for three works by Situationism-inspired affichistes that nonetheless hew to the format of the tableau (or, in the case of Jacques de la Villeglé’s piece, a kind of triptych). Kelley Walker’s appropriation of a press photograph of a plane crash turned Benetton ad turned light box piece turned Artforum cover turned light box piece yet again (2006) reads as a comment on that matrix; the use of a light box, a display device that is in wide commercial use, highlights the circulation of images between journalistic documentation, the aesthetic of advertising, and art. [3] The excursion into the present brings the constellation of theoretical vectors from the 1960s that anchors the exhibition’s discursive space up to date – with greater precision, in a sense, than Kippenberger’s monumental “Heavy Burschi” near the entrance, which actually exemplifies the opposite phenomenon: painting making a full recovery by working through the scene of its death.

The primary narrative of “Painting 2.0,” however, is a different one. Its main motif is the resilience of painting: resilience in the sense that painting takes up the challenges brought against it by technological media on the one hand and social and political conditions on the other. In their joint introduction, the three curators, Manuela Ammer, Achim Hochdörfer, and David Joselit, with Tonio Kröner in the execution of the exhibition, describe this condition as network painting avant la lettre, a form of interactivity that, rather than being made possible by digital technology, is already evident in the moments painting first grapples with the readymade, advertising, film, video, and performance art. [4] The exhibition’s central problem, however, is how such resilience relates to medium specificity, which is de facto on display almost everywhere even as it is subjected, in the networks, to theoretical – one is tempted to say, de jure – deconstruction.

The adjacent galleries, each of which is given over to a different decade, offer variations on the art-historical narrative of a tension immanent to the picture between expressive gesture and commodified spectacle, which manifests itself variously as the conflict between the freedom of abstraction and its symbols (the Statue of Liberty and the American flag in Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns); as the politicized antagonism between realism and abstraction, which is given another twist in 1970s “protest painting,” where questions of representation and political message are examined from a new angle by pictures blending political (feminist, anti-racist, or class-conflict-driven) with art-historical protest (see Daniel Buren’s cancellation of the canvas); and, lastly, as the internal conflict in 1980s neo-Expressionism, in which the return to tableau and painterly gesture is predicated on painting’s acknowledging the corruption of the subject by a debased culture (Albert Oehlen). That is the story told by the catalogue no less than the arrangement of works and wall texts in the show, and it culminates with painting “regaining its confidence” in the 1990s with works dramatizing its destruction, as in Christopher Wool’s “Incident on Ninth Street” series, where the impact that shatters painting is captured in the (photographic) image.

At the same time, the 1990s are when the new meta-media computer and Internet arrive on the scene, putting painting’s power as a visual medium to a new test and spurring the turn indicated by the exhibition’s title. Painting’s response to this challenge resembles that of an earlier competitor, photography: it translates and adapts the language of digital imagery while affirming the handmade – which is to say, subjective – quality that sets it apart from the automatically generated computer graphic. Or, at least that is one way to read this sequence, in which the underlying argument would seem to champion a painting despite everything, rather than a painting by other means. The pictures themselves, however, hint at a different story: they are neither the scenes nor the instruments of a return to a “good” materiality or physical presence beyond the world of alienating – which is to say, “bad” – digital-virtual imagery. Artists like Wade Guyton, Josh Smith, and Laura Owens instead employ digital reproducibility as a high-tech device in a form of visual production that, far from indulging in the theatrics of melancholy over painting’s irrecoverable authenticity, “updates” the antagonism by showing how the loss of authenticity is itself a wild card in the repertoire of ideological critique.

The double antithesis of abstraction versus figuration and materiality versus immateriality marks the central divide along which the exhibition’s first section links up to the two other, parallel chapters. The great appeal of this arrangement lies in the way it allows for a polyphony of diverse (re)constellations of an art-historical epoch. The focus in “Eccentric Figuration” is on the question of the (female) body of painting and, more importantly, the body in, or after, the painting-as-body. Cy Twombly’s and Joan Mitchell’s works, which remain committed to abstraction but already display an awareness of its internal conflicts, are brought face to face with early paintings by Eva Hesse in which bodies are embroiled in what might be described as a struggle against abstraction’s color fields. Expressionist gestures become “affective,” articulating a consciousness of the subject’s fractured nature and ineluctable physicality. [5] This matrix unfolds in an extrusion of painting into space (Paul Thek, Nairy Baghramian) before being folded back into painting: the picture-as-body is absorbed by the material facticity of the body in the picture (Georg Baselitz, Philip Guston), a development that ultimately culminates in the disintegration of the body itself or its transmutation into a “prosthetic body.” Its disfigurations populate painting, rendering the subjects questionable and generating new figures of sentimentality (Jutta Koether) that have nothing in common with the traditional painterly expression of emotional interiority as the paradigmatic subjective capacity. In this “retelling,” each chapter would seem to present its own “chronicle” of painting after 1960. Yet the show does more than retrace an alternative art history that has in fact by now become canonical. That is because, as an “exhibition of painting” – and be it painting 2.0, no less – it inevitably raises the question of medium specificity: in this instance, the question of what the medium specificity of a painting 2.0 might be, a painting said to respond to the media revolution by becoming “interactive” (or inter-media). So the question is also what we are to make of the digits “2.0” that figure so prominently in the show’s title, pointing to the information age as well as the interactive revolution of the Web 2.0 – which, in 2015, is not so revolutionary anymore.

“Painting 2.0” is fairly clearly not meant to be read as designating a “better,” newer, updated version of painting, a user-friendly and interactive second (and supposedly definitive) release overcoming the limitations of the painting that came before. Rather, “2.0” presumably refers to the category of “painting beside itself” Joselit outlined in a widely cited essay a few years ago: it is ultimately a trope for “(technical, media-related, medium-specific) progress,” but indelibly tinged with the irony conveyed by a painting that has been displaced into the network, a painting that is not a critique of the history of painting but a thing, an actor engaged in steady exchange with other actors – other pictures, people, things.

Inspired by a remark by Kippenberger, Joselit’s somewhat vague notion of “network painting” lets us understand “2.0” as a code whose implications are unfolded on the museum’s basement floor under the heading “Social Networks.” Yet it is surely no less urgently relevant in the arrangement in what is perhaps the most spectacular large gallery on the top floor, which is not primarily about confronting the virtualized, broken, prosthetized bodies of the information age with the intact body of painting. Rather, it constellates works in which the picture itself turns into that mechanized (Lee Lozano, Maria Lassnig), vampirish (Monika Baer), dissected (Amy Sillman), or parodied (Nicole Eisenman) body without necessarily leaving the canvas behind. Still, this dialectic becomes most virulent in the art of the past few years whose cast is thoroughly informed by digital technology, by smartphones and social networks. Even in the gallery in the museum’s basement, where this strain is strongest, the show does not simply orchestrate a pictorial lament over the unreality and inauthenticity of today’s (virtual) imagery – neither in the central gallery in which the most contemporary positions such as Seth Price’s are assembled nor in the presentation of their forebears, like Warhol’s Factory or Appropriation art. Instead, it takes techniques of copying, reproducing, and appropriating imageries that are either “base” in origin (from “single-use” [6] pictures such as Seth Price’s calendar sheets and R. H. Quaytman’s craigslist photographs of Orchard Gallery to Warhol’s pictures based on ads and newspaper photographs) or “debased” in the process of appropriation (as in Sherrie Levine’s use of Henri Michaux or Stephen Prina’s “Exquisite Corpse: The Complete Paintings of Manet”) and showcases them as “painterly” gestures in order to further dismantle the opposition of high and low, of creative and reproductive, in the polished aesthetic surfaces.

So the exhibition’s purpose is not to revive the debates of the 1960s in a spirit of melancholy, to dramatize yet again painting’s agony in the face of the deluge of commercial imagery and the technical reproduction that underlies its proliferation; it instead pursues questions of the circulation and distribution of pictures and indeed their networking among each other in order to bring something like a painting after or, yes, beside itself into focus: a “transitive painting” that stages the devolution of actions onto objects – and to say that painting, here, is an object is not to fall into the “reification trap” – and painting as what Bruno Latour calls an actor. A painting, in other words, that, not unlike the works of the Pictures Generation before it, takes inspiration from those degenerate visual registers to establish “social networks”: the concatenations or agencements of people, things, and works that produce a specific nonhierarchical milieu-as-network.

So one advantage the idea of the network certainly holds for art historians is that it leaves no room for medium specificity as a transcendental normative idea that determines what can count as painting, let alone as good painting. Instead, medium specificities – or media – emerge as one actor among others in a theoretical milieu. It is to the credit of “Painting 2.0” that it emphasizes that this shift doesn’t apply to Joselit’s “network painting” alone, but is a feature of all networked painting (including painting in pre-digital networks). Still, the title remains an odd choice. It is apt to reinforce the charge that the exhibition, a major undertaking with high theoretical ambitions, aims to elevate and canonize specific positions in art: at the dawn of the Internet of things (or, as some say, Web 3.0), the anachronism is either intentional, a historicizing gesture of canonization that makes the works on display out to be milestones of an art history that has already become a tradition in its own right; or it is not, in which case it makes even less sense that the show nowhere mentions the Internet of things, which epitomizes the networked character of today’s social sphere. It is hard not to imagine, here, that the objective, in the end, is to shore up a (quasi-modernist) medium specificity after all: to retain a conception of painting as not a “thing” but, mostly, as paint on canvas.

Tranlation: Gerrit Jackson

“Painting 2.0: Expression in the Information Age,” Museum Brandhorst, Munich, Nov. 14, 2015 – Apr. 30, 2016. Travels to: Mumok, Vienna, Jun. 4 – Nov. 6, 2016.

Maria Muhle is a professor of philosophy and aesthetic theory at the Academy of Fine Arts Munich and cofounder of August Verlag, Berlin.

The English translation of this text appears online only. Only the German language original text appears in print issue TZK Nr. 101 "Polarities."

Notes

| [1] | Albert Oehlen, "Easter Nudes," 1996 |

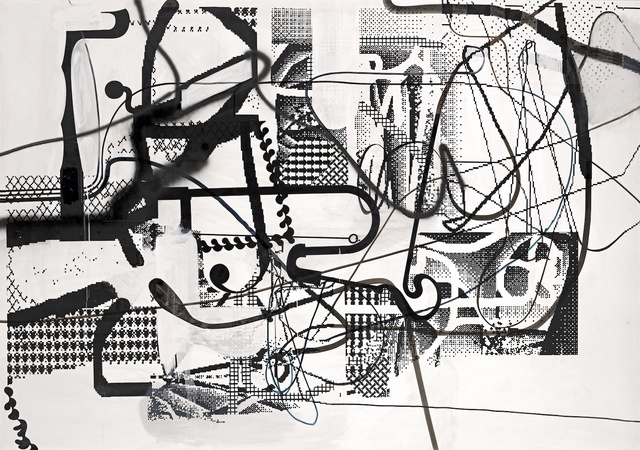

| [2] | This image and all following: “Painting 2.0: Expression in the Information Age,” Museum Brandhorst, Munich, 2015-16, installation view |

| [3] | The catalogue, unfortunately, retracts the anachronism, including Walker in the last chronologically appropriate section. |

| [4] | Manuela Ammer/Achim Hochdörfer/David Joselit, “Introduction,” in: Ammer/Hochdörfer/Joselit (eds.), Painting 2.0: Expression in the Information Age, exh. cat., Museum Brandhorst, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, mumok—Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien, Munich/London/New York 2016, 10. Hochdörfer goes on to reframe this engagement as pertaining to the essence of painting since the 1960s, whose “relevance and vitality […] rests specifically on its ability to be open to the other—to what is alien to it—which is also what brought about these upheavals” in technology and media. Achim Hochdörfer, “How the World Came In,” ibid., 16. Joselit similarly singled out the question “How does painting belong to a network?” as a “late twentieth-century problem” “whose relevance has only increased with the ubiquity of digital networks.” David Joselit, “Painting Beside Itself,” October, no. 130 (Fall 2009): 125. |

| [5] | See Manuela Ammer’s essay “‘How's my painting?’ (Judge Me, Please, Don't Judge Me),” in: Ammer/Hochdörfer/Joselit (eds.), Painting 2.0, 85–101. |

| [6] | See Inge Hinterwaldner/Michael Hagner/Vera Wolff (eds.), Einwegbilder, Munich 2016. |