DRESSING AFTER THE GREAT DIVIDE The emancipation of Jonathan Anderson

Fashion stretches the norms of gender and sexuality, transplanting elements of menswear into women’s fashions and vice versa. In itself, that is hardly a new observation – the phenomenon dates back to at least Coco Chanel’s pant skirts. What may be novel, however, is how thoroughly this impulse has permeated fashion today; it has become so common, in fact, that the term “cross-dressing” may have lost its meaning. Once the gender spectrum is fluid, there are no gulfs to be bridged, or so the London-based couturier J. W. Anderson’s designs suggest.

Sex sells? Philipp Ekardt answers with a more fundamental question: is it even still about sex? Sexuality would appear to be a minor concern today, eclipsed by an interest in community that seems to be both omnipresent and highly topical.

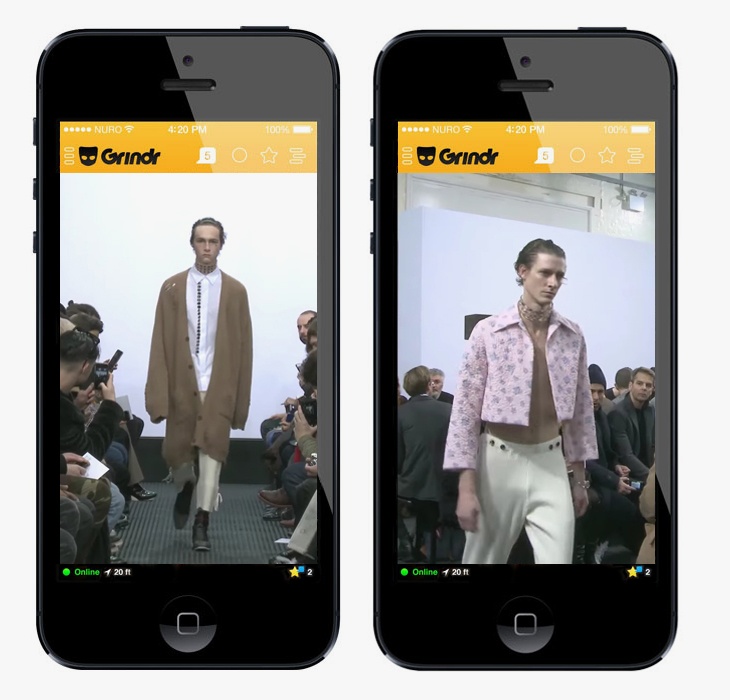

In January 2016 the designer Jonathan Anderson, one of fashion’s freshly orbiting stars, announced that he would be presenting his eponymous label J. W. Anderson’s upcoming fall/winter men’s collection via a hardly expected media channel: Grindr. Anderson, whose stark approach relies on heavy textiles, asymmetrically shaped volumes, an acute sensibility for sculpting, the occasional print (situated between the graphic and the ornamental), and off-primary yet intense colors, is a packleader in the recent exploration of what could be called – assuming, here, the aesthetic succession to the work of Miuccia Prada – a nouveau moche; a fashionable reprocessing of values categorized otherwise as “ugly.” His presentations are closely watched, and his decision to not only live-stream his show, but to use this gay dating/hookup app as a platform, pitched that attention to a considerable degree. While interested parties could retrieve a code that unlocked a conventionally-mediated online broadcast (Grindr was not, in fact, the primary host), the gesture of Grindr (a digital, social, sex-oriented portal) as (path to the) runway still generated a fair amount of attention.

Resort wear by Chanel, Biarritz, 1932

This cyber-platform has been at the forefront of reorganizing vast segments of male homosexlife by combining handheld communication technology with geo-location. Despite the jokes with respect to Anderson’s show riffing on “next look zero feet away,” what was remarkable about the resulting media coverage was the patent absence of any overt reference to questions of sex or sexuality – whether the act, orientation, or identity – in terms of the fashion that was shown. In other words, Anderson’s subsequent commentary – that he was interested in Grindr as a “sexy” community, but ultimately as a medium simply because it represented a viable platform for an initial online presentation of his designs, in its sidelining of the question of sex – seemed exactly to the point. Neither did he “sex up” his usual aesthetic by a single iota in comparison to his regular shows, nor did his designs speak to “gayness” in any way. Anderson’s choice thus certainly attracted attention due to the association with the sex/communication technology-nexus. But the internal and external processing, i.e., the reaction to the collection, as well as the looks that made up the collection as such – the clothes – weren’t tied back to sexuality, any more or less than they would have been otherwise. Ultimately, the designer had treated Grindr as “any” community, as a “mere” community, or in its pure instrumentality.

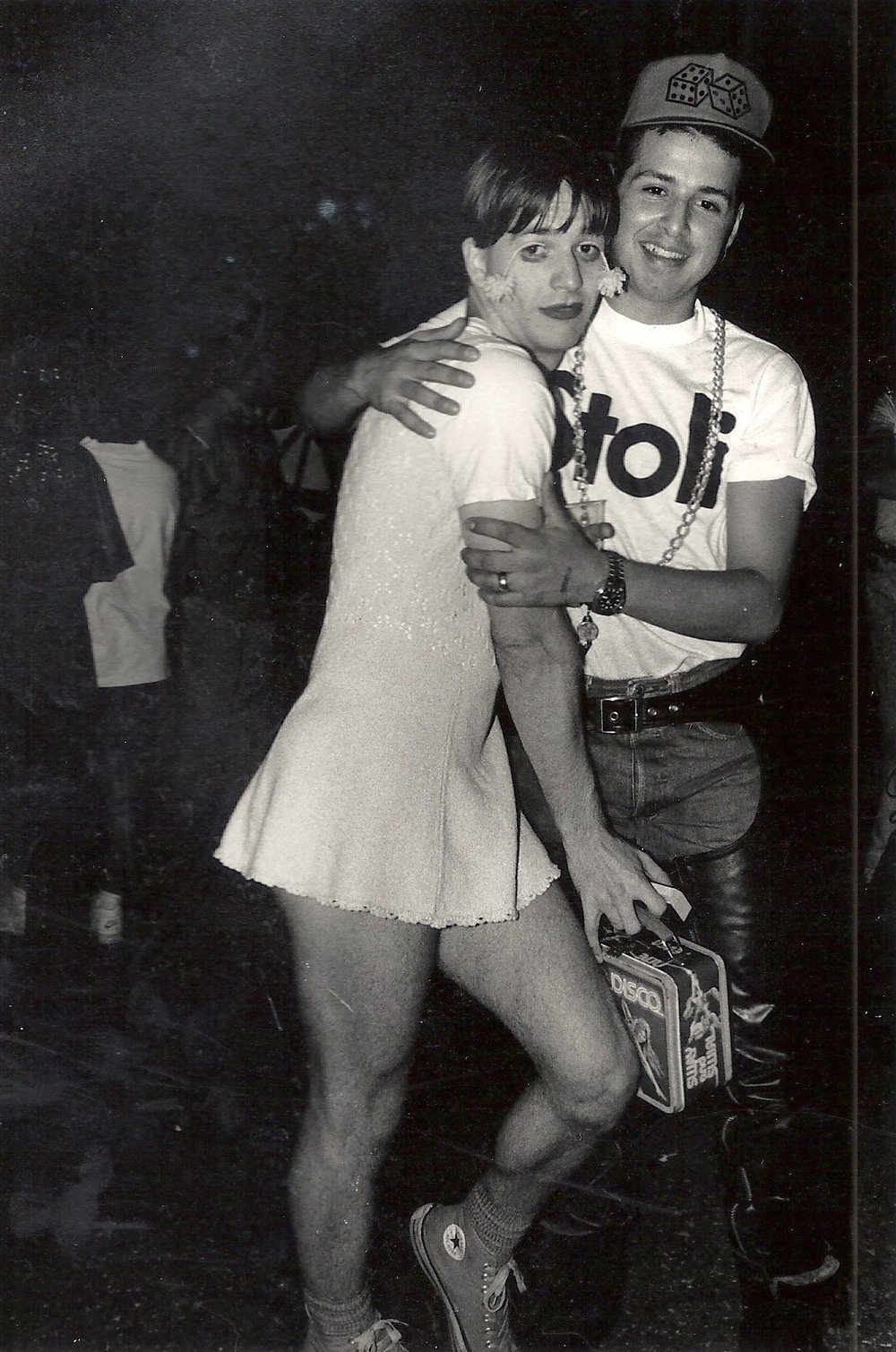

Michael Alig and DJ Keoki at Larry Tee’s Love Machine, New York, 1990

Of course, this is not to say that Anderson’s designs are generally and entirely unrelated to the question of sexuality – or gender. After all, he left one of his first imprints with his spring 2015 collection, in which he showed knitted crop tops over low-waist pants, the boyish model’s exposed abdomen certainly setting off all sorts of alarms. Anderson shared that moment with fellow London-based designers Craig Green (who, in his first collection, used the crop top as one element in his strangely formalist, ever-evolving, semi-abstract, and at times sculptural take on informal items such as kimonos, pajamas, and padded Aikido-uniforms); and Swedish, also London-based designer Astrid Andersen, who gave the theme a spin by incorporating parachute and tracksuit material. What emerged in all of these designs was a peculiar superimposition: there was the aspect of gender – the crop top being an item of clothing that, to a large extent, had been associated with “feminine” outfits (the exposed midriff the topic of ample speculation concerning a new eroticization of the female abdomen, technically the site of childbearing). But the garment also recalled two brief moments in recent fashion history where it was also seen on bodies coded as male: during the 1980s’ fitness craze, where it clothed, and revealed, the exercising core body; and during the 1990s, when it became staple raver gear.

Within Jonathan Anderson’s œuvre, one might also think of his – arguably now iconic – hot-pants, which are not “barely there,” but rather massive somehow and are, a contradictio in adiecto, given their muted colors and ready coordination with matching tops, legible as office wear (well, gone rogue). As if an oversize peplum had turned into a crotch-and-behind-covering pair of shorts, they display a softly undulating yet somehow very material frill at their lower seams. At once sculpted, cute, and formal, they are items that combine fashion values otherwise thought to be difficult, if not impossible, to reconcile. A similar case is made by a set of genuine office pants that emulate the silhouette of a (secretarial?) ankle-length skirt.

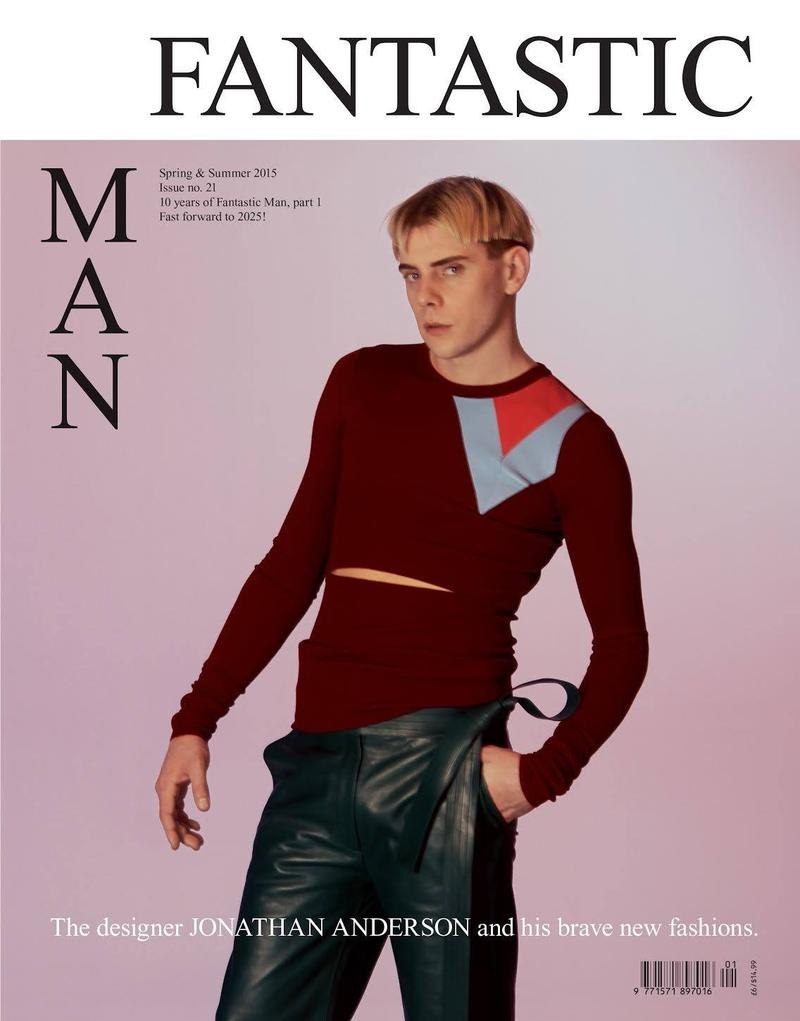

Fantastic Man, SS 2015, Cover

Looking at these pants – hot and not – one makes the observation that a shift has occurred regarding the by now classical mechanisms with which fashion has done its deconstructive gender work: we are not looking, for instance, at the invention of understatement in “female” dress qua integration of “male-coded” elements (as Chanel did it); nor do we see the construction of an allegedly “feminine” position through positing the construction of all gender qua trans-vestism (Gaultier, Mugler, etc.), as elaborated in a number of the designers of the fashion-after-fashion moment, to quote Barbara Vinken’s pathbreaking work here. [1] What we are seeing, instead, are pants that look like skirts, but are actually still pants. With this item Anderson has generated quite intriguing objects that signal in more than one gender direction, while refusing to posit themselves on either end of the alleged binary (if it still exists). It is as if the solution of the culottes – to provide women with a two-legged garment that, so as not to breach questions of appropriateness, still needed to look like a skirt – had been pushed one step further. Or as if the technical and sartorially categorizing puzzle – skirt? pants? pants as skirts as pants? – had simply outrun the question of alleged gendering.

We could extend the analysis and consider the designer’s trademark frequently sleeveless tops – wide cuts, sometimes as voluminous as a tunic, occasionally printed. Here it would indeed be difficult to tell for which gender position, if any, these items have been designed. The strategically employed wide fit makes them perfectly wearable for bodies of the most varying anatomies. These are items that are indeed produced for “feminine,” “masculine,” and bodies of all other genders. Which – mind you – is not even the case for the most basic American Apparel T-shirts.

J W Anderson, AW 2016, Live-Stream via Grindr, rendering

The image that sums it all up most succinctly is perhaps Anderson’s appearance on the cover of Fantastic Man magazine. Shot slightly out of focus, his hair parted in the middle, in an immaculate stylist’s appropriation of awkward geekiness, the designer here sports one of his designs for Loewe’s women’s line. Neither cross-dressing, nor unisexing, what we see in his work instead is a new sovereignty in the approach to the sex/gender/fashion nexus. One that has drawn all the right consequences: it takes its potential forebears in the men’s department – think Yamamoto’s flowing pants – to new constructive heights, while distributing any potential gender-work equally between both “sexes” (this used to be the prerogative of women’s wear – that it was the actual conceptual hotbed for the vestimentary elaboration of questions of gender; but no longer). Boldly formal, Anderson has clearly learned what there is to learn about fashion-SEX (in caps) from his early collaborations with/work for Donatella Versace. But while for many designers of her and her brother’s moment, sex somehow formed one center of the design universe, in Anderson’s work it has become a sweet contingency in a general reshuffling of potentials, priorities, and prerogatives. Sex is there, but only as one of many collaterals – an attitude that allows him to genuinely treat Grindr as just another (fashion) community. [2] In fact, this is what emancipation might eventually look like.

With thanks to Barbara Vinken for our conversations.

Anmerkungen

| [1] | Barbara Vinken, Mode nach der Mode: Kleid und Geist am Ende des 20. Jahrhunderts, Frankfurt/M. 1993; Angezogen: Das Geheimnis der Mode, Stuttgart 2015. |

| [2] | The same goes, in fact, for all other of the privatist, quasi-identity-based micro-communities: no “friends” on the runway here; and no easily brandable production modes exploring the vestimentary commons – hence the refreshing illegibility of Anderson’s fashion for Kimye and their kind. |