If you don’t like the reflection. Don’t look in the mirror. I don’t care.

If one considers the prevalence of personal-is-political language on social media platforms, among other regions of everyday text/speech, it is evident that the popular conscious has accorded significant power to the affective voice. Given this, it’s useful to remember that self and self-publication (person and persona) are not always aligned.

Here, New York-based writer Ada O’Higgins illuminates the distinction between different registers of interiority and desire, analyzing shame and doubt as tropes of affective distancing in a poetic comparison of subjective and objective critique.

Where does cultural criticism stand right now; is there a place for it within cultural production? Institutions of the past have been eroded, but they still exist in many sad, invisible ways. The particular discursive thought that once both depended on art institutions and served to critique them is lost. It has been replaced by a faceless mob, a cloud of views, a frenzy of likes. Criticism is an emotion now, an exposed wound reacting instinctively to what it is presented with. There is no need to engage in the charade of objectivity. There is no knowledge without a knower, and no knower who does not feel. Objective criticism has become the poetic object, the one that you hold in your hands with wonder and clutch by your side when you feel alone. Emotion, meanwhile, is now supposedly a convincing mode of criticality.

The fantasy of objective criticism, of rationalism, is one largely indebted to male -intellectuals, be it Socrates’s skepticism or the politics of Enlightenment reason. Immediacy, sensitivity, rage, vulnerability, hysteria: these modes of contemplating and reacting to culture are traditionally linked to female ways of thinking. Once, only men were thought of as capable of reasoned cultural criticism and analysis. To create and value an emotion-based type of cultural commentary can thus be seen as a feminist gesture that seeks new ways of interacting with the constant, hysterical flow of content being produced and shared. The stereotypical image of a woman screaming and fainting at the sight of blood comes to mind. It makes no sense to hide behind the pseudo-impersonal oak-paneled walls of patriarchal traditions of academic critical writing when the impersonal has lost meaning, when every click you make is public.

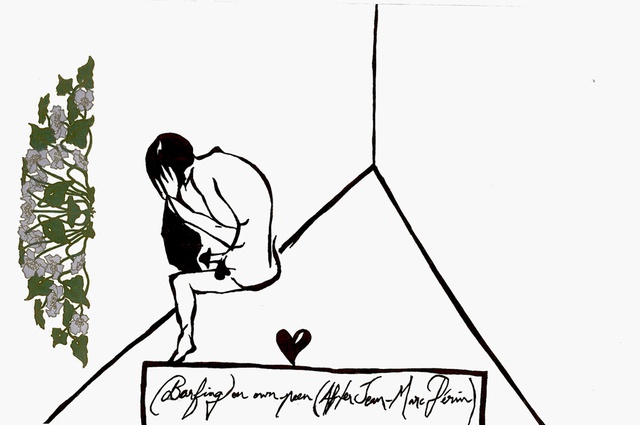

Upon waking up and checking your phone, you may feel repulsed, and you may feel the sudden urge to barf on your own peen – a concept invented by Guelph, Ontario-based artist Jean-Marc Perin: you are so consumed by shame and disgust for the world and more importantly for yourself that you feel the impulse to vomit on the sickeningly empty signifiers of your identity (here a phallus which, regardless of gender identity, can stand in for that which can never live up to its promise, only to its failure). Anyone can gag at the momentary sense of self-alienation that comes from looking in the mirror. The Internet is a bathroom occupied by thousands of people, with everyone thrust into each other’s intimacy. We’re sinking in a quicksand of images but we remain tethered to words, to the structures of language that can’t be as easily manipulated as those of the image. We’ve been using visual codes as a language but it’s not enough; all this time, words have been thriving in the shadows of imagery, taking on a new life. We thought there could be no more boundaries after queen Madonna, no more taboos. But each word contains a trap – one that was not created by us or for us, but taught to us. More urgent than the right to be seen is the right to be hidden, to dissimulate, to have secrets – to be inconsistent, to be so much more than a flat pixelated image. There are things in the shadows which you can’t see in the glow of your phone.

Ada O'Higgins, "Screaming at past fears," 2016

Ada O'Higgins, "Screaming at past fears," 2016

The more you reveal about yourself, the more thirsty your audience becomes. But there’s still a private part. They may know how you look naked, in a specific pose, under a certain lighting, but they don’t know what it feels like up there in your pussy. How dark it really is.

Imagines maiorum is the Roman tradition of making funerary masks of ancestors who achieved high public office, so that they would not be forgotten. The word “imago” also refers to the final adult stage of an insect – the point at which, having passed the larval stage, it casts off its disguise to finally embody the true look of its species. Every image is a memento of a death. But it is also a coming of age – a casting off of the vague vagaries of childhood for the seriousness of static representation. Images were once used to remember the dead, kept in gilded frames by the bed watching over the sleep of the living. But images are no longer stable; they no longer “remember,” functioning instead as a fluid media of communication. Photographs that were once silent are now constantly speaking: a new chaos of images, words, and symbols re-mixed for each individual’s purpose yet containing a universal quality (evident through the prevalence of meme humor, for example). It is now the moments that have escaped photography that are most memorable, that are sanctified by the lack of documentation imposed on them.

In the medieval tale “La Châtelaine de Vergy,” when the princess and her lover confess their passion to each other after a long silence, they become doomed and eventually discovered and killed. Derrida concluded that every time you disclose your desire, you sentence it to death. This is the bitter feeling of guilt that comes from allowing your intimate thoughts to openly seep into what you say, do, and propose online. But revealing too much about yourself produces a sense of relief. In this sick process of counter-shame, people can’t judge you for things you disclosed to them with your own gaping mouth. Maybe you don’t want to small talk so instead you say too much, or maybe you post something too real. You get home and there’s the regret, the need to barf on your own peen. Because you gave them a lot, for nothing, for free. And the more you openly reveal your secrets, the less, you know, you’ll be able to cum – because the less taboo these things have become within you. In jeopardizing your own privacy, you may or may not be jeopardizing your capacity to feel joy, to experience the ecstasy of those who keep secrets.

Notes

| [1] | Ada O'Higgins, "Barfing on own peen (After Jean-Marc Périn)," 2016 |