Notes Toward the Memes of Production

View of Barbara Streisand’s Malibu residence

View of Barbara Streisand’s Malibu residence

If affect is one factor playing an outsize role in the rise of populism, media strategy stands as another – with reactionary beliefs, fomented in the communicational channels of blogs, comments sections, and image boards, now taking hold in broader arenas.

While some might argue that engaging these spaces risks further normalizing the regressive ideas they harbor, it is nevertheless crucial to look beyond this ideology to analyze the machinery that has engendered it. Here, Matt Goerzen takes up viral media – i.e., memes – examining why and at what point the Right came to dominate this means of cultural production and how the Left might again take control.

.

UNTIL RECENTLY, the internet meme had largely been regarded as a politically negligible media object: a peculiarly iterative aesthetic container deployed by internet users to typically comedic – and occasionally profound – effect. But in 2016, an assortment of right-wing users made a provocative claim: that they had “memed” -Donald Trump into the White House.

And scrolling through the increasingly popular imageboards (like 8chan’s /pol/ and /bmw/ boards) [1] where these users gather, one encounters a common refrain: “The Left can’t meme.”

MEMES & GENES

If this is true (and it just may be), it wasn’t always the case. The term “meme” was coined in the 1970s by the evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, who conceived of it as a “unit of cultural transmission” that spread from “mind to mind.” [2] By this, Dawkins conceptualized memes as correlates to genes – replicable building blocks that determine the body politic, just as genes determine the body proper; like genes, the “fitter” the meme, the longer it would hold influence. Languishing on the fringes of social science for decades, the term “meme” itself might have been lost to linguistic evolution were it not for its recuperation, in the early 2000s, by users of 4chan and similar sites who adopted it to describe the peculiarly iterative, participatory media objects central to their activity. [3] On these web-based channels, aesthetic production was (and remains), thoroughly anonymous, with authorship collectivized – unlike in the art world. Attempts by non-users (“normies”) to appropriate and thus reify such memes would be met with virulent pushback. [4]

Woodcut, c. 1400

Woodcut, c. 1400

In their Dawkinsian sense, memes are total in their production of the social. Some have even theorized them to be no less than producers of consciousness itself [5] or applicable to broader-form concepts such as religion. In Dawkins’s framing, these “viruses of the mind” could be flourishing memeplexes, deeply entrenched in the cultural fabric of our lifeworlds; they were “mind parasites,” capable of colonizing their hosts over the course of lifespans and generations, shaping the politics of this or that society. This deterministic aspect of memes, however, was initially downplayed with the concept’s ’00s recuperation to describe the participatory, spreadable media objects and gestures engendered by the internet. [6] However, these latter-day memes are increasingly understood as capable of steering discourse and understandings in the fierce attention economies of contemporary networked media environments. [7] Beyond the musings of think piece writers, memes are now taken with the utmost seriousness, by entities ranging from DARPA US military researchers and NATO agents to ISIS’s ideological warriors – all of whom see the form as a contemporary weapon of war. [8]

According to the conspiratorial Right, the Left, largely due to the efforts of the Frankfurt School, was once proficient at what we now call “memetic warfare.” In the new Right’s version of events, the school advanced more than a theoretical critique of cultural production (as a capitalist, industrial pursuit). Rather, they advanced a process of “cultural Marxism,” whereby the Left deployed critical theory to successfully dominate mainstream political conversation – and thus seize control over the critical sites of normative cultural production [9] (the media, the academy, the art world, or what many contemporary reactionaries call the “Cathedral”). In this conspiratorial framing – offered variously by neoreactionary bloggers, chan trolls, and contemporary neo-Nazis – the danger of the Left is located precisely in its historical success at seizing these means of cultural production, and by extension, the “memes of production,” too. Everything from globalization to the rise of political correctness is traced to this purported hegemonic bid. [10]

Cathedral Notre Dame d’Amiens

Cathedral Notre Dame d’Amiens

While some might argue that engaging this reactionary culture risks further normalizing its regressive ideas, it is urgent to look beyond the ideology: to peer into the machinery delivering its memetic payloads. [11] After all, to defend against a weapon – or even to take it up for oneself – it is prudent to understand how it works. As will become clear, the new Right has appropriated these tools from earlier generations of Leftist cultural warriors – and configured them for a new battlefield by embracing anonymous social media technologies. The memetic Right understands the 20th-century avant-garde as a memetic warriors par excellence, masters of media who deployed critical theory and attentional strategies to disrupt and detourn the status quo of their time. Examples abound, whether it be Letterist International members trollishly mounting the Notre Dame pulpit in Dominican habits during the televised 1950 Easter mass in order to proclaim the death of God, or Quebec’s Les Automatistes, whose 1948 memetic manifesto “Le Refus Global” prefigured the province’s Quiet Revolution, delegitimizing the region’s Catholic Church in favor of a secularist value system premised on aesthetics and anarchic socialism. Pointedly mainstream liberal activity likewise follows here – not least, the CIA’s international promotion of Abstract Expressionism during the Cold War in order to memetically reinforce Western cultural values.

Yet the new Right asserts that as this liberal memeplex obtained normative discursive dominance, it proved incapable of making good on its claims of social progress. To spread this conception to a wider audience, the Right hit on an effective strategy: they could exploit the liberal media’s obsession with novelty and bleeding ledes to piggyback anti-liberal ideas into the mainstream on the back of “start-over monikers” like “alt-right” and transgressive memes like Pepe the Frog. And in so doing, they could mobilize existing antagonisms toward the political establishment, cultures of political correctness, and globalization, ultimately baiting the liberal media into revealing inconsistencies that could act as catalysts for their own, alternative platforms – or, as the Right might put it, effectively seizing the “memes of production.” [12]

THE NEW RIGHT AND THE MEMES OF PRODUCTION

Emerging in the early 2000s from the memetic broil of online imageboards as a full-blown subculture, trolling is the practice of engendering “lulz” (a transgressive form of schadenfreude-like humor) by eliciting from their targets embarrassing, often compromising reactions. The fastest route to the lulz, trolls discovered, was to adopt politically incorrect rhetoric and/or subject positions (the anonymity of these digital platforms being a key facilitator of this) and “raid” external communities (e.g., brigading comments sections and flooding social media groups). In this activity, internet memes – whether as bait, shibboleths, or iterative archives where the lulz could be recorded for posterity – proved to be particularly well suited techne. Exceptionally responsive to the rise of competitive attentional media, memes evolved, in turn, from the cumbersome memeplexes of yore into agile ideological delivery systems capable of rendering masses of minds receptive to new information via small but incremental instances of exposure. [13].

But where was the liberal Left during this efflorescence of new-right activity? Largely critiquing or resisting technological forms and rhythms it would seem. [14] Looking at the past few decades of contemporary art, it’s clear that many Left cultural producers opted to avoid capital-intensive technological engagements, favouring instead embodied relational aesthetics, participatory media, and explorations of social identity formation. [15] Also disqualified on moral grounds by the liberal Left – but not the Right – has been the use of “cognitive hacking,” a memetic attack that relies on manipulating human users’ perceptions and corresponding behaviors to achieve its goal (the services of data profiling firm Cambridge Analytica being a signal example here). [16] To implement such a divisive campaign would be, in the eyes of the Left, a form of debasing the individual’s right to personal agency. And given this rationale, it may therefore be less correct to say that the Left can’t meme, than that it has simply declined to. [17] The contemporary Right, meanwhile, has no such qualms. Characterized by a diffuse alignment of chan trolls and white supremacists granted an intellectual scaffolding by “neoreactionary” blogs (devoted to ethno-nationalism, men’s rights, transhumanism, and “race realism,” among other anti-liberal positions) and amplified by such broad-reach platforms as Reddit, Twitter, and Facebook, the memetic right has inserted its ideas into the political mainstream with remarkable efficiency.

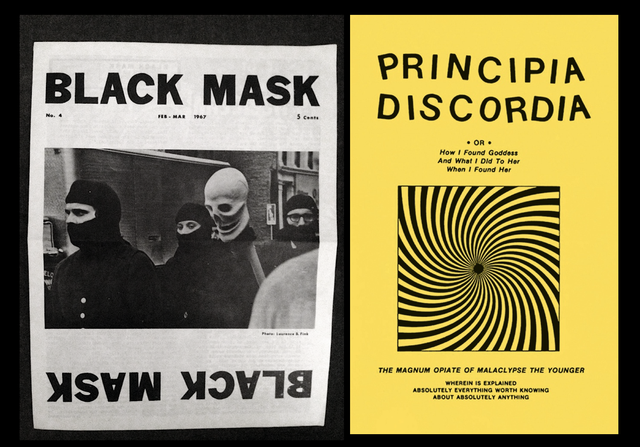

Ben Morea, “Black Mask,” No.1 (New York, 1967); Greg Hill and Kerry Wendell Thorniez (1965), “Principa Discordia” (Loomatics Untld., 1979)

Ben Morea, “Black Mask,” No.1 (New York, 1967); Greg Hill and Kerry Wendell Thorniez (1965), “Principa Discordia” (Loomatics Untld., 1979)

As with earlier avant gardes, the memetic Right’s tactics succeed by wedding the pleasure of transgression with novel formal invention and detournement – seducing, thereby, a clickbait-oriented, novelty-obsessed news media into addressing its content. [18] As the memetic Right’s activity is routed along attack vectors already well-traveled by previous generations of trolls, the pathway is well groomed for more popular adoption. Complimenting this, right-wing media pundits increasingly hail the new Right’s activities as proof that the Right is the new punk rock – a veritable counter-culture. [19]

A word, here, about “novelty”: Fascist and racist ideas are, to be sure, not new . However, these ideas – like a tired consumer product given Wi-Fi connectivity and a contemporary veneer – have been repackaged and rebranded by the contemporary Right in ways that have rendered them as exceptionally novel . In turn, media gatekeepers have pounced on the Right’s memes, even unpacking them (and thus performing free memetic labor) for their respective audiences. For some, these actions remain rooted in a jouissant pursuit of lulz. But for others, the memes function as Trojan horses – means to open the “Overton window,” seeding mainstream political conversations with ideas that would not, via normative channels, ever be permitted space for consideration. Thus, due to the sticky properties of memetics, far-right ideas about race, gender, and national borders have been given airtime – with all attempts by establishment authorities to properly frame and debunk them only spreading the ideas further afield, delivering their memetic payloads into more minds: the “memes of production.”

LIBERAL MEMES AND DEFENSIVE MACHINES

But just what are these “memes of production”? What do they involve? Certainly, activists operating within the boundaries of the liberal public sphere have utilized memetics to political effect in recent years. #blacklivesmatter offers an emblematic example – spreading rapidly as a hashtag, an intelligible vessel for complex ideas, and an organizing coordinate for embodied activism. Its aim is socially progressive, and yet its power is still limited. Why? How could an initiative promising to make lives better and society more fair and safer not become memetically dominant? While some on the Left may claim the #blm memeplex is too radical to take hold in American society (or likely any European one), an alternate theory would be that such memes, structured as they are in line with ’60s-era activism, ultimately rely on organizational modes long prescribed by the establishment from which the oppression stems. Filling the already-sanctioned space for “democratic protest” and “healthy resistance,” such memes, the latter argument claims, do not open the Overton window and thus lack the alternative scaffolding necessary to imagine a viscerally captivating mode of systemic change.

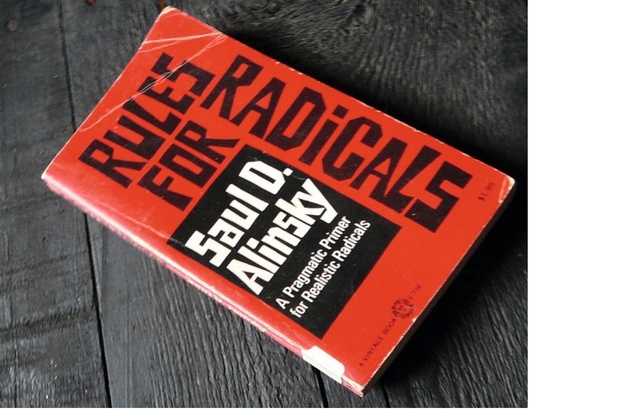

To seize the “memes of production” requires, by contrast, a more substantial attack (one in line with past avant-garde strategies) on the very structures that underwrite the conditions of publicity and the public sphere itself. In turn, these bids set the stage for alternative platforms to join the mainstream as the forces they promote gain power (e.g., Trump and Breitbart News). [20] Efforts by liberal authorities such as the Hillary Clinton campaign and the Anti-Defamation League to renarrativize a meme like Pepe the Frog as evil (thereby ascribing it a univocality and power it did not previously possess) only signal to antagonistic onlookers more significant vulnerabilities in the Left/liberal power structure. And of course these lulz-inducing (well-meaning but ultimately naïve) attempts at censorship only further the spread of the Far Right’s memeplex. [21] Leftist calls to “no platform” far-right organizers are negated by the liberal media’s willingness to not only amplify the right’s activity with detailed coverage (of, for example, a then largely-unknown Richard Spencer’s assembling of less than a hundred neoreactionaries in the fall of 2016) but to frame this coverage in a way that sensationalizes it. [22] It is difficult to imagine how these ideas would have ever entered mainstream conversations were it not for the liberal media’s own accelerant, attentional rush – a process that has ultimately served to weaken the liberal media’s credibility even in the eyes of its own broader audience. [23] In another irony not lost on the Right, this very strategy was one examined by Hillary Clinton in her doctoral dissertation, which took as its subject the activity of leftist organizer Saul Alinsky, who famously wrote in his classic 1971 text “Rules for Radicals,” “The job of the organizer is to maneuver and bait the establishment so that it will publicly attack him as a ‘dangerous enemy.’ The hysterical instant reaction of the establishment [will] not only validate [the organizer’s] credentials of competency but also ensure automatic popular invitation.”

It may be entirely understandable why the liberal status quo has failed to address these memetic vulnerabilities. Whether by design or incidence, neoliberalism has historically proven exceptionally good at co-opting its most virulent attackers, even as it publicizes them. Herbert Marcuse describes this as “repressive tolerance,” whereby the most palatable elements of a threatening group are folded into the status quo (perhaps cracking open the Overton window, though only a minute amount), thereby weakening their more extremist allies. But this defense mechanism may ultimately be ill-suited to the current task: inviting in racists and xenophobes has already proven to effect not just a change in temperature, but a literal change of state.

It is difficult to know what the Left/liberal public sphere – and the political system to which it is bound – might do to correct itself. But where one attacker finds an opportunity, another might as well. What if the Left did choose to meme (effectively)? And if it did, would certain values, norms, and myths need to be recalibrated? Would this weaken or indeed prove to strengthen progressive aims?

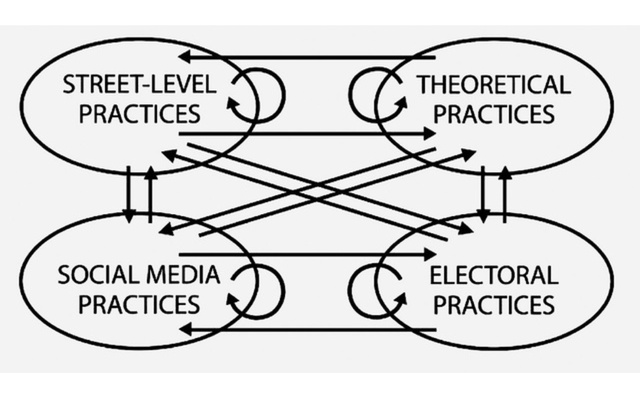

Diagram from ANON’s “#AltWoke Companion,” 2017

Diagram from ANON’s “#AltWoke Companion,” 2017

THE MEMES LEFT BEHIND

Alongside the rise of neoreactionary blogs and libertarian techne like 4chan, some young contemporary artists, weaned on the net, were engaging in their own experiments with memetic techne. Artistic “surf clubs” like Nasty Nets and a community project called The Jogging (whose content bled into blogs across Tumblr to be taken up by clickbait-dedicated news websites and beyond) explored the potential for autonomous, collective production outside of the established art world. [24] Closer to the mainstream, trend-forecasting/artist group K-Hole took up the role of cultural gatekeeper, offering poetical “trend reports” that effectively prescribed the terms of co-option for their own cultural communities to marketers. Their term “normcore” stands as a tremendous memetic success, if one also quickly rethematized to suit the very co-opting market logics they sought to trouble. [25] In all these instances, however, the relationship between value and author status led the individuals central to these attentional-economic feats to retire their more autonomist, collectivist ambitions in favor of established culture sector hierarchies and economies. Much of their subsequent gallery-ready work is now assigned the term “post-internet” art. Similar complications have also arisen in the explicitly leftist production of “feminist memers” on Instagram, and communist meme accounts on Facebook. Their syntheses of intersectional politics and traditional Marxist coordinates with trendy memetic containers have proven popular among other users, and media outlets like Buzzfeed and Vice have profiled them extensively. But the communities are self-reflexively burdened by their reliance on sites where attentional success often translates into literal economic gain – for both the most prominent practitioners and the techno-capitalist platforms that ground their activities. [26]

It is a profound irony that right-wing memetic production owes much of its success precisely to a strident disavowal of both authorial status and individuated property. Rather than making bids for gatekeeper positions in existing social arrangements or reward in established markets, they largely embrace anonymity and pseudonymity toward a broader war against the establishment itself – viewing even recognizable containers like Pepe, Richard Spencer, or Donald Trump as collective platforms instrumental in the pursuit of higher-order agendas. Meanwhile, they slowly build the infrastructure for their own economies (rooted in, e.g., micropayment Patreon accounts for popular pseudonymous bloggers and crowdfunding platforms like WeSearchr).

Facebook Campus, Menlo Park, Carlifornia, 2015

Facebook Campus, Menlo Park, Carlifornia, 2015

SEIZING THE MEMES OF PRODUCTION

With the American Far Right now capitalizing on its mainstream attentional successes toward ambitious alternative projects, some on the Left – often risking pariah status within their own discursive circles – have responded to this new memetic ecology not by recoiling, but by taking notes. Bracketing outrage as an end in itself, they appear keen to understand and even co-opt the tools and mechanics that have enabled these populist platforms, pundits, and political imaginaries – the Breitbarts, Mike Cernovichs, Keks, and Calexits [27] – to command such prominent attention and appeal. It is territory in which many post-internet artists have taken an avid interest: analyzing and unpacking technological cultures, often attempting to steer these assemblages’s own resources toward ulterior ends. [28] But with these tools seized, where might cultural producers look to find tantalizing messages and political imaginaries worthy of memetic amplification – ones able to offer viable progressive alternatives to audiences unconvinced by existing left-liberal coordinates?

On 8chan, an anonymous /leftypol/ community has already surfaced – counter-mirroring /pol/’s interest in esoteric racists like Julius Evola with their own recuperation of historically waylaid figures like the egoist anarchist Max Stirner (a drawing of Stirner by Friedrich Engels circulates there as a configurable “reaction image” akin to Pepe).

Closer to the discursive coordinates of contemporary art, a memetically-ambitious “Left accelerationist” group calling itself the “Alt-Woke” has invested in this ambitious task. [29] Departing from Nick Land-style accelerationism (which advocates an embrace of inhuman techno-capitalist logics until a planetary breakdown occurs), the Alt-Woke gestures toward a more narrowly practical, if vanguardist interest in the political affordances of emerging technologies; a kind of “Left accelerationism” that aims to maneuver these powerful processes to progressive ends. The group has announced its position in avant-garde style via an “Alt-Woke Manifesto,” publicly sharing this statement as a read-only Google Doc. The communiqué, which collectively identifies its authors by the name ANON, [30] exhorts the limitations of identity politics and advocates for a leftist engagement in “memetic warfare.”

But these ambitions face overwhelming challenges. Though the Alt-Woke’s memes draw on proven memetic containers, they frequently point to theoretical coordinates that demand rarefied knowledge and acculturation to be sympathetically received. Meanwhile, those who are invested more directly in academic discourse tend to be unconvinced by the group’s theoretical admixtures. And even as some might welcome a praxis capable of circumventing (or temporally bracketing) the decelerating micropolitics and discursive deadlocks common to agonistic and identity politics, the Alt-Woke’s own centering of these theories (even if to attack them) seems to have only invited further dissonance among its already minuscule target audience.

By contrast, the memetic Right’s appeal is immanent. It attracts adherents with the lure of easy transgression, achievable by little more than identification with its appropriated mascot: Pepe, the cartoon embodiment of the misunderstood (male) outsider, misread by those unwilling to understand his nuance, and transformed into a hate symbol. An embrace of the Pepe frame means, for this group, freedom from the very agonism now offered by the Left: freedom from moral burden. The theoretical articulations as to why this may feel so “liberating” can come later – if at all. [31] And though the emergent Right reactosphere is replete with its own bitter infighting and factional disagreement, these differences are set aside when there is fun to be had: an establishment to be trolled – with lulz as reward.

As the sticky narratives of leftist movements like Anonymous and Occupy fade from memory, it is worth wondering around what imaginary a new insurrectionist memes of production could arise. Gazing toward “problematic” technologic horizons, one finds projects like FairCoin, a cryptocurrency mutual fund aimed at economic redistribution. Already funding internationalist Left initiatives like the YPG – the Kurdish confederalist anarchists fighting to establish an egalitarian society in the midst of a war-torn Middle East – these projects struggle to attract popular support from attentionally-deficient Western audiences, even as their potential to ground memetic political imaginaries seems untapped. [32]

Nevertheless, as the Right now consolidates itself into a position receptive to attack, the Left has begun edging toward an embrace of the techne its opponent has proven so effective. Sped along by the strategic ignorances of platforms designed to forget and memeplexes configured to remember, will some find ways to escape the traps of authorship, performance of self, attention economy market value, and personal brand maintenance – find freedom to play, to meme, and even maybe to troll? It seems a fitting time to wonder: Just what memes may come?

Notes

| [1] | 8chan.net is an imageboard that became popular in 2014 after a number of users left 4chan due to censorship concerns. /pol/ (or Politically Incorrect) is dominated by conversation about race, immigration, gender, “meme magic,” and political philosophies like anarcho-capitalism and fascism. /bmw/ (the Bureau of Memetic Warfare) is used by a smaller group of users to discuss the application of memes to political activism and psychological warfare. |

| [2] | Richard Dawkins, The Selfish Gene, Oxford 1976. |

| [3] | “The [Dawkinsian] meme concept has been the subject of constant academic debate, derision, and even outright dismissal,” writes Limor Shifman in Memes in Digital Culture, Cambridge, Mass. 2013. |

| [4] | For example, after both Nikki Minaj and Katy Perry posted Pepes to their Instagram accounts in 2014, 4chan users responded by creating a stream of “poo poo pee pee Pepe” memes with the intent of coding the character as so marked by debased associations as to render further uptake untenable. |

| [5] | In Consciousness Explained (Boston 1991), American philosopher Daniel Dennett writes: “Human consciousness is itself a huge complex of memes (or more exactly, meme-effects in brains).” |

| [6] | Instead, theorists of the internet meme have emphasized unique formal properties and the participatory social behaviors that constitute their production: “The depiction of people as active agents [as opposed to determined subjects] is essential for understanding internet memes, particularly when meaning is dramatically altered in the course of memetic diffusion,” writes Shifman in ibid. |

| [7] | Influence professionals have found that instantiating new memes (“forcememing,” in the parlance of the chans) is exceptionally difficult, but that memes can be attached to new themes with new narratives once they’ve been accepted – in this manner functioning as Trojan horses. |

| [8] | See, for instance, DARPA’s Social Media in Strategic Communications research project, and Jeff Giesea’s “Memetic Warfare” paper in NATO’s Defence Strategic Communications journal: http://www.stratcomcoe.org/academic-journal-defence-strategic-communications-vol1. It should also be noted that these papers are widely shared on sites like 4chan and 8chan. |

| [9] | See: Ben Alpers, “The Frankfurt School, Right-Wing Conspiracy Theories, and American Conservatism,” http://s-usih.org/2011/07/frankfurt-school-right-wing-conspiracy.html. |

| [10] | Right-wing pundits are fond of quoting Andrew Breitbart’s dictum that “politics is downstream from culture.” See, for instance, http://iasc-culture.org/THR/channels/Infernal_Machine/2017/02/politics-is-downstream-from-culture-part-1-right-turn-to-narrative/; and for how the Frankfurt School fits in: http://iasc-culture.org/THR/channels/Infernal_Machine/2017/04/politics-is-downstream-from-culture-part-2-cultural-marxism-or-from-hegel-to-obama/. |

| [11] | This is not to dispute the wisdom of leaving dangerous ideas dormant. But at the time of writing it is clear that opportunity with this material has passed; at least in North America, the liberal media now airs these ideas daily. The critical questions become: how was the media was so effectively gamed? And what happens next? |

| [12] | The detournement of the “fake news” narrative is emblematic of this point. Initiated as a liberal meme to condemn factually incorrect clickbait articles, anti-establishment pundits – including Donald Trump himself – have effectively renarrativized the meme and applied it to the liberal media establishment itself. |

| [13] | A useful concept here from communications theory is “Shannon entropy” – the rate of communication being dependent on how familiar the receiver is with the components of what is being communicated. Specifically, this term is invoked to describe how assimilating entirely new information requires the receiver to expend more energy, thus making communication more difficult. The iterative function of memes lowers the barrier to assimilation by building new meaning on the back of already internalized and processed understandings, requiring less energy for the assimilation of each successive thematic or narratological pivot. As such, memes can more easily bypass cognitive “security” mechanisms primed to reject ideas that challenge already-internalized “protected beliefs.” |

| [14] | Notably, the most compelling articulations of a neoreactionary politics have come from Silicon Valley insiders. Peter Thiel, for instance, is a primary funder in Urbit, the tech startup of Curtis Yarvin, aka Mencius Moldbug (widely regarded as the intellectual father of neoreactionism). And Balaji Srinivasan, a partner in venture capital firm Andreesen-Horowitz, has publicly advocated for the exit of Silicon Valley from the United States, in favor of a political restructuring that closely resembles Moldbug’s envisioned “patchwork” of corporate micronations. |

| [15] | This turn can, perhaps, be tied to the corruption of the California Ideology – the persistent countercultural belief that networking technologies would necessarily elicit a restructuring of economic and social relations along more decentralized, egalitarian lines. See: Richard Barbrook/Andy Cameron, “The California Ideology,” http://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/californian-ideology. |

| [16] | This term comes to me by way of Rand Waltzman, former head of the SMISC (Social Media in Strategic Communications) program under DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency). See: http://time.com/4064698/social-media-propaganda/. For example, there is mounting evidence that firms like Cambridge Analytica used data profiling to mechanistically influence particular personality types into particular voting behaviors during both the 2016 US presidential election and the Brexit campaign. See, for instance: Carole Cadwalladr, “The great British Brexit robbery: how our democracy was hijacked,” https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/may/07/the-great-british-brexit-robbery-hijacked-democracy. |

| [17] | With the move toward postmodernism, Left and liberal cultural producers could be understood as having largely moved away from modernist, technological, formal developments and toward critique, interrogations of identity and relationalist affect, and agonistic politics. |

| [18] | For example, the new Right has detourned such existing pop-cultural tropes as “red pill” – a term derived from “The Matrix,” where the protagonist is offered the choice between a red pill (revealing the world as it really is, pitched here as what the new Right offers) and a blue pill (allowing a return to blissful ignorance, i.e., what they frame the left-liberal position to be). Many media outlets are prompted to unpack these rhetorical developments, thus spreading the memetic payload to new audiences. |

| [19] | I.e., Infowar’s Paul Joseph Watson: https://youtu.be/avb8cwOgVQ8. |

| [20] | This includes new media platforms like Breitbart and WeSearchr, and also social media alternatives like Gab.ai. |

| [21] | Media theorists call this the “Streisand Effect,” named after an incident wherein Barbara Streisand sought to have photos of her house that had been viewed only a handful of times removed from the internet, whereupon the news of this attempt directed thousands of eyes to the pictures. |

| [22] | Whitney Phillips’s This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things (Cambridge, Mass. 2015) offers a thorough account of this symbiotic relationship between trolls and the liberal media. |

| [23] | The Right further demonstrated its memetic mastery by co-opting the liberal media’s “fake news” meme and steering it back at them. A September 2016 Gallup poll found that American trust in the mainstream media was at an all-time low: just 32%. Notably, right-wing and Republican survey respondents reported at only 14%. See: Art Swift, “Americans’ Trust in Mass Media Sinks to New Low,” http://www.gallup.com/poll/195542/americans-trust-mass-media-sinks-new-low.aspx. |

| [24] | Notably, The Jogging was inspired by the production style of 4chan, as explored in an essay by co-founder Brad Troemel, “What Relational Aesthetics Can Learn From 4chan,” http://artfcity.com/2010/09/09/img-mgmt-what-relational-aesthetics-can-learn-from-4chan/. |

| [25] | Normcore was first proposed by K-Hole in “Youth Mode: A Report on Freedom” as a strategy for “opting into sameness” in order to temporally participate in various communities. In its appropriated version, it came to describe a basic mode of dress – and frequently appeared attached to fashion shows and GAP clothing collections. Of course, mere entry is not itself politically salient, and may be almost guaranteed to fall into a liberal-progressive style of creeping normative politics – but it does present the possibility of transvaluation by seizing sites of cultural production. |

| [26] | Indeed, many of these “memers” are themselves enticed into exhibition at commercial art galleries. And some have engaged in displaying branded content for advertising purposes. These activities premise highly agonistic community discussion about the merits of being paid for content generation – and by whom – and the hierarchies these economics introduce between content producers. |

| [27] | Kek is an Egyptian frog-headed deity who anons identify with Pepe the Frog. They seek to channel him as a “hypersigil” using numerological “meme magic,” and, whether ironically embraced or not, it has proven a powerful community playframe. Calexit is a memetic bid to see California – and Silicon Valley – become politically autonomous from the broader United States, as prefigured in the writings of neoreactionaries like Mencius Moldbug. |

| [28] | I am thinking here of a range of trollish engagements I document in my masters thesis, “Critical Trolling,” perhaps most succinctly emblematized by Simon Denny and Daniel Keller’s detournement of the Ted Talk promotional apparatus to stage artistic critiques of the very techno-capital regimes it services. |

| [29] | The term “woke” is a linguistic meme, emerging from black political communities to describe politically awakened individuals. As the manifesto elucidates, its ironic adoption is an attack on those who would see the term’s uptake by non-black communities as “problematic.” |

| [30] | http://tripleampersand.org/alt-woke-manifesto/. |

| [31] | The memetic right offers its entrants various “red pills,” informational blasts which rupture established liberal narratives and invite the initiated into progressively more comprehensive engagements with neoreactionary theory and historical revisionism. |

| [32] | Journalistic accounts of Western leftists like “PissPigGrandad” who join these anarchist fighters have already opened the Overton suitably window leftwards in interesting ways – but they have yet to find encapsulation in sticky memetic forms. |