DECADES OF IDENTITY POLITICS By Coco Fusco

Lyle Ashton Harris, „Ektachrome Archive (New York Mix)“, 2017 (Kinshasha Conwill at the Black Popular Culture conference, Dia Art Foundation, New York, 1991)

I understand why Texte zur Kunst has focused on 1990 as a benchmark for this discourse, however identity politics, in my lived experience, has been an evolving debate that actually began in the late ’70s in relation to the establishment of minority cultural spaces and ethnic studies, then moved into discussions of Black feminism and Black masculinity, before merging with a multiplicity of debates in the 1980s – relating to institutional critique, post-structuralism, feminism, etc.

Identity politics has acquired such negative connotations over the years that I cannot help but think of it as a derisive phrase at this point. I recall the dismissive attitudes that prevailed in the art world and in the press in the 1980s toward artists of color in general and toward multicultural policies that were being promoted by some philanthropists and arts agencies. This stance was to some degree a reaction to the political pressure from governmental funding bodies to attend to a more broadly defined public and the philanthropy world’s growing interest in ethnic populations, as well as the new markets these populations represented. Funding art was seen as a way to make inroads in those communities. The American avant garde, up to that point, had only exhibited interest in cultural difference as a storehouse of references to draw on or be inspired by: Navajo sand painting, jazz, African masks, and so on. The privatization of culture and the simplification of the previous discussions into conversations about personal identity changed things quite radically in the 1990s.

People forget now just how exclusionary the art world was before 1990 and just how smug the arts establishment was about its Eurocentrism. I remember Venezuelan artist Rolando Peña, in 1987 at the press conference for Documenta 8, complaining about the virtual absence of artists from Latin America, Africa, and Asia – and being booed. I recall being compared to Rush Limbaugh in an art magazine around that time because my pro-multiculturalist stance was deemed “strident.” And I remember when I brought John Akomfrah, Isaac Julien, and other members of Sankofa and Black Audio Film Collective to present their work in downtown Manhattan in 1988, how the enlightened white intellectuals in the audience marveled at the Black British artists’ eloquence as if this were surprising. A handful of surveys that showcased artists from diverse backgrounds (I am thinking here of exhibitions such as “The Decade Show,” which was staged across three NYC institutions – the Museum of Contemporary Hispanic Art, the New Museum, and the Studio Museum Harlem – in the summer of 1990) was cast as nothing short of a barbaric invasion, a deplorable loss of concern for aesthetic values, etc. On the other hand, famous postcolonial academics such as Edward Said, Homi Bhabha, and Gayatri Spivak were embraced by the arts establishment and published in art magazines. Theory with a foreign accent was easier to digest than garden-variety American ethnics who wanted a place at the table.

It is important to also keep in mind that in the multicultural debates of the 1980s, the art market was not really a central issue. Perhaps this was because, at the time, few non-white artists had consistent gallery representation or even regularly sold their work. The focus was on institutions and funders – on what museums weren’t doing, on how aesthetic innovation was understood by funding bodies in ways that excluded consideration of what non-white artists made as valuable and valid. But that decade would give way to the culture wars of the early 1990s, in which multiculturalism was vilified, followed by the privatization of culture. This ushered in the explosion of market interest in contemporary African-American art, along with the globalization of contemporary art collecting at large. In turn, the market would play a significant role in diminishing the political organizing around issues of identity. The long-term result of that shift is that today identity politics plays out in very different ways, with much narrower demands – public debate is focused on attacking individuals in the name of imagined communities that are in reality quite fractured. Much less effort is put toward systemic analysis of institutional practices or organized demands for inclusion. That is an unfortunate consequence of the market’s dominance in contemporary art, and the failure in art schools to globalize curricula and teach postcolonial analysis seriously. It is painful for me to witness how young artists focus solely on what they see as the individual “right” to represent a culture or history rather than looking more broadly at the policies and practices of art and educational institutions. There is little sense of history or of the ways that identities are commodified by everyone in today’s art market.

1990 was not a “starting point” for me – I think it is remembered now as a beginning because mainstream museums and art magazines started to cede space to non-white artists around that time. It was clear that offering separate cultural venues for minorities – however important some of these spaces have been – was insufficient and certainly not equal.

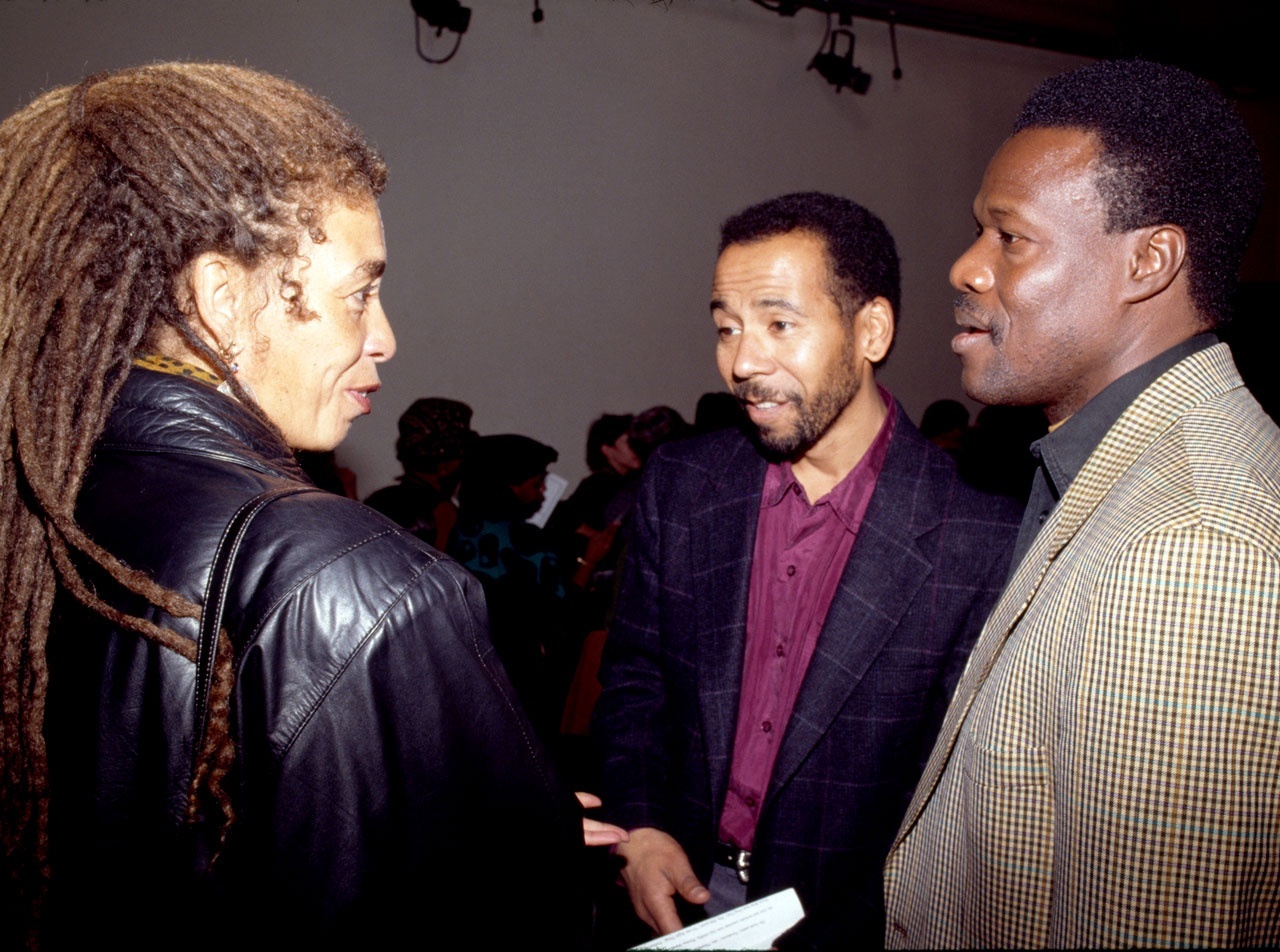

Lyle Ashton Harris, „Ektachrome Archive (New York Mix)“, 2017 (Angela Davis, Ed Guerrero, Manthia Diawara at the Black Popular Culture conference, Dia Art Foundation, New York, 1991)

My involvement began in the 1980s, when my generation of post-civil rights beneficiaries of affirmative action came of age. We were aware of a longer history of struggles by Black and Latino arts professionals who were concerned about the lack of ethnic and gender diversity in exhibitions and galleries, on curatorial staffs, and in the aesthetic judgments that opened doors to grants and shows and museum collecting practices. We also were influenced by critical theory: by anti-colonial thinkers such as Franz Fanon and by radical filmmakers in the Third World with their critiques of conventional cinema and their desire to merge political and aesthetic avant gardes. We had graduated from universities where we had tried to challenge Eurocentric curricula. But we were also concerned about what we saw as limiting aspects of monolithic notions of identity and “correct” modes of cultural expression that were supported by cultural nationalists. We were influenced by Black feminist critiques of the demand for unity and were skeptical about the insistence that positive images of community were an ethical imperative for minority artists. In my memory, the late ’80s and early ’90s were about striving for a critical and nuanced engagement with issues of cultural representation. As such, the terminology we used in the ’80s was different from what is used now. We did not talk about subalterity then – only Spivak did. We talked about colonialism, neo-colonialism, anti-colonialism, etc. These terms framed our inquiries as investigations of systems, not individuals – and this is the problem I always have had with “identity politics” as a framework. We referred to debates as being about multiculturalism not identity politics. If and when “identity” was the central point of discussion, as was the case in Stuart Hall’s “The Question of Cultural Identity” (1992), it was addressed as a term to be analyzed from many angles. Hall drew on sociological debates about the “crisis of identity” (i.e., its decentering) as a symptom of the undermining of conceptual and ideological frameworks that gave people a sense of rootedness in their world. Hall urged us to consider hybridity, our ways of inhabiting a range of identitarian subject positions. He underscored that these identities were not biological but historical. At the same time, Hall was acutely aware of how racialization processes in modern societies impute fixed identities to non-white subjects.

Regarding your last question, where you’ve asked me, “In what ways does the identity of the artist alter the way we understand a work of art and whether this has changed in some way in recent decades?” I take this as a question of how the perception and interpretation of works has changed, to which I would say: the degree to which identity shapes understanding really depends on the level of sophistication of the viewer and the political imperatives that underlie the public display of the work. The debates about multiculturalism from 25–30 years ago were about institutional racism and also about how to elaborate aesthetic endeavors that were expressive of cultures outside the mainstream. Because exclusion from mainstream institutions and the art market was the experience of the majority of non-white artists, there was a greater sense of unity about the need to press for greater institutional inclusion than there is now. At the same time though, there were a variety of positions with respect to aesthetics and how and whether one’s identity should be taken into consideration in evaluating one’s work. Non-white abstract artists often found themselves ignored by minority and mainstream institutions since their work could not be touted as a narrative illustration of minority experience.

The globalization of the art market and the notoriety of a handful of non-white artists in the US – who for the most part are African-American, since other minorities have not had the same degree of market success – have had a profound effect on how “identity politics” plays out in the present. The goal of most of the young Black artists I encounter today as a professor is market success, not political or aesthetic transformation. Identitarian concerns are a double-edged sword – too much focus on cultural politics can make you a pariah at an elite art school and undermine sales, while some degree of cultural referencing allows for easy identification and attracts a certain kind of favorable attention. And the mainstream art world has become more sophisticated about how it negotiates with otherness as well. References to ethnic and cultural difference that can draw a crowd to an exhibition, please a funder, or secure private donations are good. But politicized engagement with art education and institutions that challenges those who remain in power is still definitely not ok.

Image credit: Courtesy of Lyle Ashton Harris