UNTITLED Avery Singer on Laura Owens at the Whitney Museum of American Art

“Laura Owens,” Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 2017/18

I remember learning in school that there was a poem written about itself; however, it concealed this self-referentiality through its own form. I cannot remember either the title or its author, but what has stuck with me over the years is the interpretation. The poem describes its own beauty, but never explicitly acknowledges itself as the subject. The example of the self-reflexive poem is an apt metaphor for how to understand the unique logic of Laura Owens’s paintings. The time necessary to read the poem, decode it, consider its meanings, is analogous to the time required to read the composition and references embedded within one of Owens’s paintings. This specific time frame could be characterized by the dueling factions of the quick and the slow, narrative whimsy and technical virtuosity. Owens’s paintings produce their own temporalities, in which the viewer becomes synchronized, achieved in the juxtaposition of mechanical and manual labor. The act of zooming in on a digital page, or using the brushstroke tool to wipe away a layer in a Photoshop file, captures both transitory and highly subjective digital experiences. If Owens’s particular mode of pictorial space-building had a name, it might be called “temporal illusionism,” for it presents the arena of time as a pictorial illusion.

The space of painting can be pictorial, optical, social, cultural, historical, theoretical, subjective, collaborative, anachronistic, or conceptual – and any combination or permutation of these variables at once. Owens has been experimenting with these various terrains since the mid-1990s. For example, on the eighth floor of the Whitney Museum’s recent retrospective of Owens’s work, in a single installation comprised of several canvases, both stereopsis and binocular disparities in depth perception are depicted – a massive and challenging undertaking. Silk screen, complex masking, heavy-bodied acrylics, hidden speakers, canvases concealed like Matryoshka dolls, and various sculptural objects are incorporated into or protrude from Owens’s canvases. It would be hard to find a material or technique that Owens has not utilized at some point.

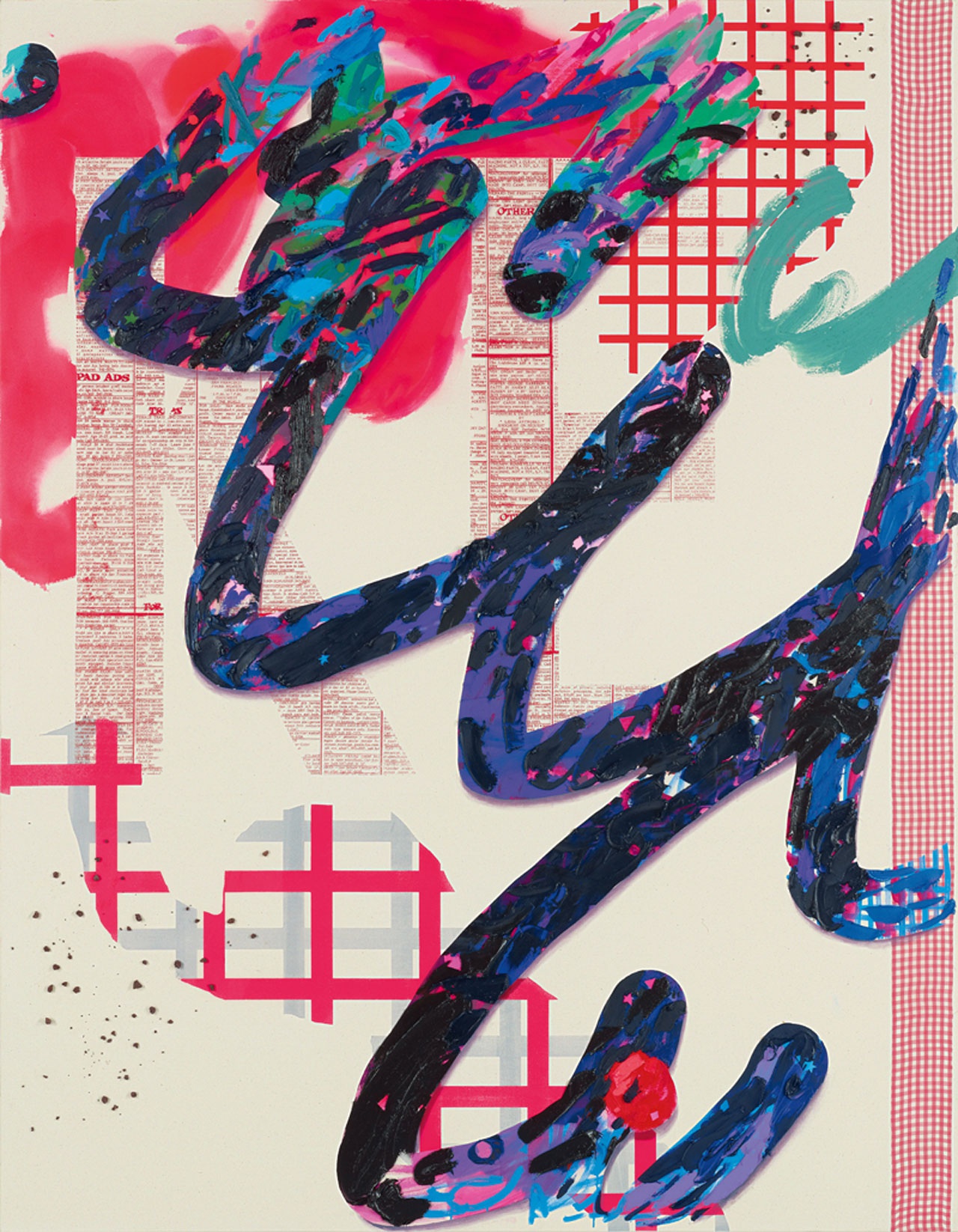

Laura Owens, “Untitled,” 2012

Curated by Scott Rothkopf, the retrospective reformulates works through a series of well-conceived curatorial moves. Initially, we are greeted with a painting of pictures hanging salon-style in an otherwise empty green room; parallel red lines on the floor demonstrate the recession of space into the horizon of one-point perspective. The painting has been cleverly hung next to a smaller work that is halved into raw canvas and light teal, suggesting a horizon line with a sky and water, or if flipped, a desert and sky. The positioning of these two paintings is particularly revealing, as the latter has upward slanting lines on the canvas’ edges, sloping in the same direction as the red lines in the adjacent painting, suggesting that the former contains imagery depicting retreating Cartesian space on these typically forgotten zones: the sides of the canvas. Two canvases comprising an untitled diptych with a connect-the-dots reference – hung opposite from one another in a small hall dividing the exhibition – are mirror images, suggesting the connection of space between the paintings, as well as spaces within the paintings themselves.

Compositions with allusions to historical depictions of the salon, artists’ studios, and viewing rooms directly follow this initial introduction into Owens’s extraordinary pictorial language, utilizing perspective and orthographic projection to delineate flat walls and neighboring objects. Paintings of paintings serve as windows, expanding and contracting painterly spaces. Feminine signifiers abound in her work as well, and while I am unable to list each instance, what I can instead identify is the strong presence of a feminine hand producing these paintings; how this hand actively questions ingrained cultural responses to femininity, craft, and the career of the female artist in the historically male-dominated field of painting. The visual and verbal debris of parenting fill her work as expressions of lofty mark-making, in the enlarged forms of childhood fairytale imagery, handwriting lessons, and games such as connect-the-dots puzzles and mazes. Fairy tales ultimately function as a placeholder for the site of primordial narratives in Western/Eurocentric painting. In an untitled work from 2014, the illegibility of images and texts serves as a joke on the task of searching for distinct meaning, the layering of marks and images a reflection on indexicality. A painting of a maze of cats alludes to the complications that arise when historians argue over definitive beginnings and endings on the time line of art history, and who the participants may or may not have been (cats = artists?).

With paintings that mark the beginning of her career – in reconstructed rooms that resemble the more humble scale of the (then) young galleries offering Owens her first solo shows (Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, Sadie Coles, Acme, and Rosamund Felsen) – Owens and Rothkopf recreate the conditions under which the works on display were originally intended to be experienced, conjoining this history with the more large-scale setting of the mid-career retrospective. Often, Owens creates site-specific paintings to fill entire gallery walls. A large suite of untitled small-scale paintings remains obscured behind the temporary exhibition architecture that showcases “Pavement Karaoke,” evoking the same gesture carried out in the obfuscation of several paintings behind a larger one in an untitled piece exhibited in the 2014 Whitney Biennial (also included in the show). Owens has also clandestinely installed speakers inside the stretcher bars of canvases (first exhibited at the CCA Wattis). The installation functions as it was originally shown, as a participatory sound piece, in which gallery-goers are given a phone number to send questions to via text message. Responses to these questions are then emitted by hidden speakers in the installation in the form of pre-recorded answers.

Detail of Laura Owens, “Untitled,” 2012

A visual salad of allusions, historical subject matter, imagery, and wildly diverse mark-making fills her work. She is perhaps one of the most stylistically mimicked living artists of our time, as evidenced by visits to art school studios and innumerable exhibitions around the United States. Style, however, is just the exterior facade of a very complicated machine. “What it looks like” is a radically incomplete view of a painting. It is important here to mention abstract illusionism, the short-lived movement that emerged in California in the ’60s and ’70s. At first glance, Owens appears stylistically indebted to this particular period. Abstract illusionist paintings abound with brush strokes and shapes depicted as flattened volumes casting drop shadows, layering the space with shallow and illusionistic forms. Most of these paintings, however, reek of motel art. Owens’s interest in these particular artistic clichés is part of a larger interest in platitudes, and she utilizes this self-conscious strategy as, essentially, a way to access “bad painting” that does not have its roots in the resistance to bourgeois culture in postwar Germany, à la Sigmar Polke. The art historian Barbara Rose identified an entirely different group of artists working predominantly in hard-edged abstraction as the “real” abstract illusionists. Published in Artforum in 1967, in an article in which she lists the main protagonists (annoyingly, almost all men), Rose symptomatizes abstract illusionism as painting that contradicts two-point perspective with a singular, dueling spatial element. Paintings in this vein continue the modernist tradition of developing painterly space that challenges pictorial illusionism. Differing claims about the movement (via internet research) are defined by a “pushing outward” of pictorial space in contrast to Renaissance trompe-l’oeil, which draws space “inward” through the depiction of cast shadows on sculptural forms. Perhaps then abstract illusionism is actually a reactionary departure from modernism. The dialectic between Rose’s investigation and the internet’s differing claims struck me as quintessentially postmodern and analogous to a duality present in Owens’s work: pastiche actors in the scene of a play where painting serves and references itself as a cultural artifact.

The assertion that paintings are about light and space seems to be a leading maxim of modernism, which is both referenced and complicated throughout Owens’s work. The group show “The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World,” curated by Laura Hoptman at MoMA in 2015, exhibited three of Owens’s paintings – one of an email, another an excerpt from her child’s handwriting lesson, and one of a newspaper clipping (not included in the Whitney retrospective); these were the first examples I witnessed of a major shift occurring in her work during 2012–13. The process of using silk screens to enlarge and reproduce newspaper clippings evokes the techniques of Pop artists, and in its execution, changed everything for Owens. Layers of elaborate screen printing, masking, gestural strokes of acrylic paint as thick as cream cheese expeditiously spread on a bagel, and objects such as stones, wooden grids, and bicycle wheels protrude from the surfaces of canvases from this period. For the “status” of painting, however, these works propose an even more complicated answer. David Joselit writes in his essay “Notes on Surface: toward a genealogy of flatness” that “there is a great deal at stake in acknowledging that the flatness or depthlessness we experience in our globalized world is more than an optical affect […] flatness may serve as a powerful metaphor for the price we pay in transforming ourselves into images – a compulsory self-spectacularization which is the necessary condition of entering the public sphere in the world of late capitalism.” [1] The light of Owens’s paintings from the era of her “Pavement Karaoke” show at Sadie Coles in 2012 emerges from a flattened and smoothed-out gessoed white ground, which was achieved through the careful sanding of countless layers – evoking the white background of an e-mail on a computer screen, or the white of a page – by eliminating the canvas’ texture.

Abstraction and representation have ceased to exist as ideological categories for decades. The meaningfulness of sentences (or lack thereof) in her compositions is demonstrative of this categorical nonexistence. Formally, text used in Owens’s paintings serves not so much as a conceptual device, but as a series of semi-legible shapes available to the artist as compositional tools. Mass-market source material such as newspapers, notepads, wallpaper, emails, and advertising are reproduced and enlarged to span the entirety of the canvas’ surface. They reflect our oversaturated modes of receiving information and encountering images. Our subjectivities have changed since Andy Warhol silk-screened portraits of world leaders and celebrities onto monochromes, but strains of nihilism depicted through technological and mechanical means is a thread that runs through both his and Owens’s use of the medium. Our reality, unlike Warhol’s, is faced with the threat of technological apocalypse – Y2K, cyber warfare, cryptocurrency volatility, and hacking scandals – the development of which cannot be underestimated. We are obscenely overloaded both with existential threats and meaningless information.

Being an artist is like finding yourself in a pitch-black room with no idea where the switch is to turn on the lights. You fumble, feel around without any guidance, and hope to finally one day find the switch. Laura Owens has been consistently flipping switches for nearly 25 years. Her paintings, at first glance, seem to be about everything but themselves: e-mails, stories, collages, newspapers, distraction, doodles. Despite appearances to the contrary, the works are actually every bit about painting itself: self-reflexive works that address the context in which they are rooted. The attempts and failures to understand signs, symbols, and texts in her work play with our desire for legibility – and is ultimately a great joke about the search for discrete meaning in art. Her methods of representing light and space in the digital age remain very much her own. It may not be salient to parse which of these conceptual techniques prevail over the other, as they seem to all occur simultaneously within her work. Certainly, however, I’d say that Laura Owens better continue flipping switches, so she can continue to light the way.

“Laura Owens,” Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, November 10, 2017–February 28, 2018.

Avery Singer is an artist living and working in New York.

Image credit: Courtesy of Laura Owens, Sadie Coles HQ, London, Gisela Capitain, Cologne, and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Note

| [1] | David Joselit, “Notes on Surface: Toward A Genealogy of Flatness” in: Art History , Vol 23, No. 1 (March 2000): 19–34, here 20. |