WORK-LIFE IMBALANCE Melanie Gilligan on Jasper Bernes's "The Work of Art in the Age of Deindustrialization"

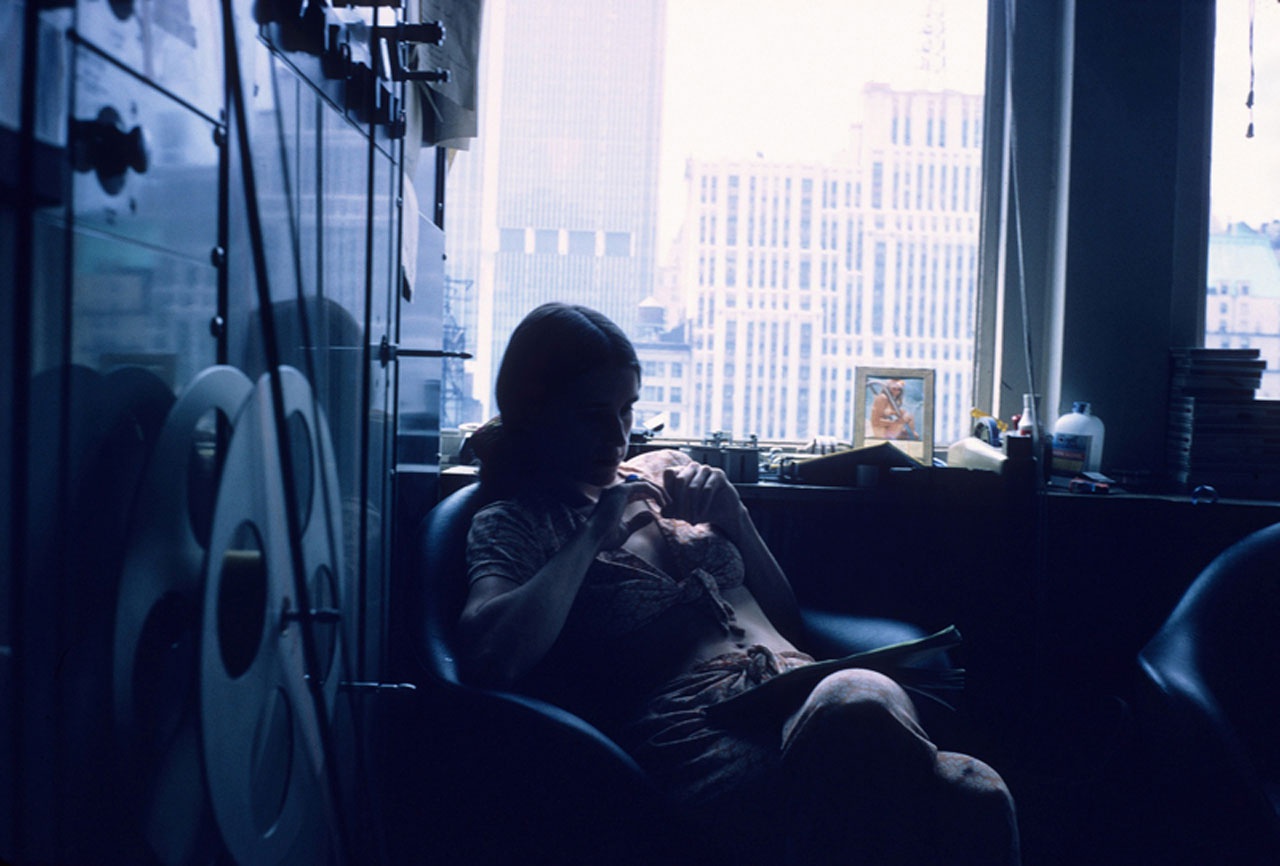

Bernadette Mayer, “Memory,” 1971–72

Bernadette Mayer, “Memory,” 1971–72

As manufacturing dwindled in postwar America, the expansion of white-collar office and service sector work not only shifted the balance of employment but established a new orientation for labor. As the tumultuous social revolutions and labor struggles of the 1960s and 1970s brought with them worker demands for more control and creative, fulfilling jobs, they were met with a round of brutal but covert innovations from capitalist enterprises. By engineering textures of autonomy and routines of self-management into the work experience, labor could be re-signified as no longer oppressive but instead a context for collaborative team efforts, as all the while intercapitalist competition drove a restructuring that intensified and rationalized work. Businesses found new, aestheticized modes of functioning that promoted the implementation of flexible and horizontal labor practices while encouraging collective participation and affective intensity in the workplace. In this way, conflict was reconfigured and diffused though, of course, by no means extinguished.

This change was not effected by the corporate world alone. In the 2000s it became clear to artists and theorists that art itself was somehow complicit in these changes, that some kind of insidious collaboration between art and business had taken place. However, even though the period saw much discussion of the “culturepreneur,” as well as links between the new economy and creative industries, this did not result in specific answers regarding how such a shift had come about and what techniques and mechanisms had effected these changes; nor were they analyzed in relation to the larger economic transformations of the 20th century. [1] Jasper Bernes’s The Work of Art in the Age of Deindustrialization revitalizes such a project by examining the indirect channels that connected practices and values through which art provided models for new paradigms of white-collar employment in the global North. While acknowledging from the outset that the book’s work is transdisciplinary, Bernes’s primary attention is unavoidably devoted to his own field, poetry. Yet it is heartening to come across a project comfortable enough to move between aesthetic disciplines and include lengthy discussions of visual art alongside passages from novels and television dialogue. Artworks, for Bernes, function as sites where the techniques and ideologies of future labor conditions are developed, “in most cases, against the intention and conception of most artists and writers themselves.” The book shuttles between aesthetic, economic, and social inquiry to tease from works of art qualities of a nascent social reality still in formation. The restructuring of capitalist social relations in Bernes’s history is often not causal but rather takes place through “elective affinities” between practitioners, works, and across social spheres. Artworks are understood to exert their influence diffusely while businesses absorb these and counter-pose their own ambient social forms, or, in other cases, impart them directly when artists simply work for a white-collar wage.

The book opens on two portraits in the latter vein, those of New York School poets Frank O’Hara and John Ashbery. O’Hara composed Lunch Poems during his work-days as a curator at the Museum of Modern Art. A poetics of reported social intimacy, splendorous interiorities, and an “intimate yell” taken from Mayakovsky, all under the sign of the commodity, O’Hara’s Pop-lyric style lined up painter, film star, and composer proper names with brand-name products. In an extended discursus on the love poem “Having a Coke with You,” Bernes demonstrates how the poem’s evacuation of authenticity lends itself to a more hallowed attention to the beloved. The experience that the product facilitates is, in O’Hara’s hands, a strange refinement of the lyric as a technology for disengagement, of “deep acting” within the context of 1960s employment in the service sector. Bernes suggests that this particular brand of lyric poetics was especially useful for suggesting modes of fine-tuning the person-as-affective-product as part of the inculcation of new practices needed to ensure the “quality encounters” of a burgeoning experience economy. Likewise, specific works by John Ashbery lead us to observe the circular relationship between art production and capital’s processes of domination, in which artists learn from transformations in the world of work while inadvertently contributing new lessons to it. At its apotheosis, the discussion burrows deep into the poet’s singular uses of free indirect discourse, a type of third-person narration in which thoughts, feelings, and speech – divisions between experience and the social world – become indistinct. The “welter of points of view and modes of address” evinced in Ashbery’s The Tennis Court Oath, Bernes tells us, can be understood as having been produced by the conditions of decentralized divisions of labor and power in 1960s office work, the commodity form of labor as lived in the fragmentary assemblage of the internal and external parts of people – their voices reassembled in hierarchies abruptly displaced, workers indiscernibly playing boss and employee, their class positioned as performed. Undulations in literary time-space, “a social ventriloquism through which white-collar workers simultaneously speak and are spoken for,” configure shards of “administrative language coursing through capitalist firms” in a tangle of exploitations.

By focusing on crossovers that developed in 1960s New York between poetry and art, Bernes demonstrates how social and systemic dimensions threaded through the practices of artists. The shared lexicon of process art, chance-based compositions, “happenings,” interventions into daily life, and disruption of artist-spectator dynamics laid the groundwork for a widespread reception of the science of cybernetics. Artists employed its theoretical framework, particularly its concepts of information and feedback, in order to model social systems, and as a result these artists “both prefigure and contribute to the actual restructuring of the labor process.” To demonstrate this, Bernes focuses on performative poetic works by Hannah Weiner and magazine pieces by Dan Graham that display operations that made information transmission central, while the communicative content is stripped and language converted in an attempt to render transmission transparent and, as such, subversive.

Bernadette Mayer, “Memory,” 1971–72

Bernadette Mayer, “Memory,” 1971–72

What follows is a close reading of Bernadette Mayer’s photographic and sound installation work Memory (1972), which provides a view of feminized clerical work: historically low-paid in relation to (equally gendered) managerial, professional, and technical white-collar positions. Every day for a month, Mayer wrote and shot a roll of film chronicling her daily activities, condensing the resulting material into a recorded reading by Mayer alongside a presentation of the photographs. The visual and written components of the work strongly diverge in tone, however Mayer’s spoken arrangements of everyday language and fantastical form give a pulse to the piece as she recounts fragmented experiences, including the act of making Memory itself. Bernes identifies an important thread that runs through the work in the daily labor and life chores that ceaselessly punctuate Memory, as Mayer multitasks between waged and unwaged forms of work: shopping, cooking, traveling, running errands, various modes of information management, phone calls, and bumping into people. The parataxis tightens as the hours become denser, too hurried for the poet to “make decisions” or “gain direction.” Mayer’s situation is emblematic of the “double day” of on the one hand women’s wage labor, and on the other the unpaid domestic labor and all-consuming manifold of time invested in the care of other people, served up in the blend of work and leisure time pioneered by artists, later to be perfected on the job market at large. The artwork, Memory, assembles and exhibits the problems of being, simultaneously, a mother, a partner, and an artist making such a project, all of which relies on the historically loaded work of typing and sorting documents. In other words, the repetitive clerical labor that Mayer performs in order to make her work recalls Benjamin H. D. Buchloh’s diagnoses of Conceptual art as an aesthetics of administration. If only the link between the aesthetics of administration and a historical view of women’s work were made more frequently!

By the time Mayer confronts a life obliterated by abstract time, we have the sense that the book’s narrative presents us with an impasse in capital’s own conditions of possibility. For Bernes, the transformations he speaks of in labor practices are necessarily mediated by technology; for instance, throughout his account of the restructuring of work, Bernes interweaves the role of digital information technologies with that of 1960s and 1970s countercultural resistance. Technological changes in the labor process are necessarily temporal. Elsewhere, Bernes describes technological developments in capitalism as “path-dependent,” which means that they are not politically neutral but take shape in capitalist contexts that strongly influence the possibilities of what can come about in the future development of those technologies. [2] Against the unremitting documentation of past time in Memory, Bernes develops a further analytic for thinking the time of labor – past, present, and future. Capitalism tends toward crisis through contradictions created in its use of technology. In Capital, Vols. 1 and 3, Marx discusses the relationship between the dead or past labor accumulated in the tools and machinery used for production and living labor. In order to thrive, capital must constantly expand itself and expand the use of technologies to increase productivity. As production becomes increasingly efficient, labor is expelled, but since the capitalist mode of production relies on labor’s exploitation, this creates a self-undermining dynamic that results in a growing surplus population that lives outside the wage. As the book draws to a close, Bernes comments that “in another mode of social reproduction this relationship to the past might look more like forgetting that Memory,” eluding to the domination of living by dead labor and the constraints exercised on future labor in digital workplace regimes.

What would it mean for Bernadette Mayer not to administer her husband’s work while straining to make her own art, while also working to earn a living, caring for her family, and fielding personal and business calls? What if she simply cares for the things that are needed? Of all of the book’s inestimable strengths, one of its greatest virtues is that while it tells a social and cultural history that overlays the aesthetic with the economic, it acknowledges foremost that this history is one of violent transformation. Passages consisting of close analyses of works churn their materials so that, thus agitated, the reader might infer how the world could be different. [3] Bernes’s book comes to a close where the conditions of possibility for his historical account dissipate. In the wake of deindustrialization America evaded high unemployment by forestalling it through, among other things, [4] the cultivation of a low-wage service sector, but this situation is increasingly unsustainable. In conclusion, Bernes leaves us with fragments of a poem by Wendy Trevino about work in an office. [5] Trevino’s defiantly frank delivery provides powerful final passages that register the intolerable quality of the present. For Bernes, the poetry and art to come will still relate to its economic climate – this probably cannot be avoided – but no longer defined by work, it will more likely find form in the disparities of wealth and the limbo of wageless life.

Jasper Bernes, The Work of Art in the Age of Deindustrialization, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2017.

Melanie Gilligan is a Canadian artist living in New York City who works in video, performance, text, installation, and music.

Image credit: © Siglio Press and the Bernadette Mayer Papers, Special Collections & Archives, University of California, San Diego

Notes

| [1] | Appearing throughout the book are the arguments of Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello in The New Spirit of Capitalism. Also relevant here is The Mental Labour Problem by Andrew Ross. From 1998 to 2000, Anthony Davies and Simon Ford produced an important series of articles on the merging of art and business that took place in the 1990s and 2000s, and in the process, coined the term “culturepreneur.” Brian Holmes developed the concept of the Flexible Personality in The Flexible Personality: For a New Cultural Critique. |

| [2] | Jasper Bernes, “The Belly of the Revolution: Agriculture, Energy and the Future of Revolution”, in: B. R. Bellamy/J. Diamanti (eds.), Mediations, Winter 2017. |

| [3] | Jasper Bernes’s Logistics, Counter-logistics and the Communist Prospect, Endnotes (2013) begins with a discussion of theory as part of the clarification of struggle which is pertinent here. |

| [4] | As is well known, general economic decline in America was also delayed or simply masked through the continuous supply of low-cost consumer goods, consumer credit, housing, and financial bubbles. |

| [5] | Wendy Trevino, “Sonnets of Brass Knuckle Doodles,” in: Boog City Reader , 8, 2015. |