MEDITERRANEAN BORDERLAND

How can it be that SOS signals sent by a boat in distress for several days are received by every single ship in the area, yet elicit no response? How have right-wing politicians in Europe succeeded in rallying broad parliamentary support as they have rationalized and enforced policies that flagrantly flout minimum humanitarian standards?

Literary scholar Ashna Ali describes the Mediterranean as a fluid yet lethally effective border that is perpetuated by a wide range of actors. Shattering romantic projections of the sea’s mystical opacity, Ali’s analysis reveals structures that, after 2017, have exacerbated the situation in the Mediterranean even as public attention has seemingly moved elsewhere.

As the political landscape of the Global North and beyond skews heavily to the right, debates around migration and ethno-nationalism dominate global public discourse. The increasing militarization of borders in both the US and the EU requires a reassessment of the understanding of what kinds of spaces and materiality constitute “borderlands.” The conceptualization of borders as bifurcations of land obscures the reality of the Mediterranean Sea as one of the world’s deadliest and most surveilled borderlands, and the site that may have catalyzed the recent surge in European xenophobia and ethno-nationalist fervor. In 2015, the world’s eye turned toward the Mediterranean as thousands of African and Middle Eastern migrants lost their lives between the Libyan and Italian, Maltese, and Greek coasts. For two years, images of stunning blue water dotted with bright orange inflatable dinghies overburdened with passengers flooded global news media. Outrage over the failure to provide adequate medical support and political protection for asylum seekers spiked with highly circulated photographs of a Kurdish Syrian child, Aylan Kurdi, whose body washed up face-down on the Turkish shore after he and many others on his boat drowned in their attempt to reach Greece. This image made Kurdi the poster child for what came to be known as the European Migration Crisis.

The European Migration Crisis and its alleged “end” in 2017 prompts the consideration of some crucial questions: whom do we hold responsible for the migrant deaths at sea? If the “crisis” is over, what happened to the millions of people fleeing from civil war, persecution, poverty, and climate catastrophes that continue to destroy their homes and jeopardize their lives?

Hakim Abderrezak names the Mediterranean a “seametery” in order to call attention to the regional specificity of the deaths of migrants coming from predominantly Muslim countries, arguing that “the sea with its associated notion of fluidity has failed to function as a stitching (seam) apparatus between countries, continents, and cultures with a longstanding history of conflicts.” [1] That these tensions are long-standing is scrubbed from media coverage of the crisis. Though migration into Europe through Italy and deaths in the Central Mediterranean are far from new, clandestine crossings of the Mediterranean came onto the world radar only in 2015, the deadliest year on record, with over 5,350 estimated deaths at sea. [2] Before 2015, Operation Mare Nostrum, an Italian naval and air rescue operation, is credited with having saved thousands of migrant lives on the Mediterranean. However, this humanitarian effort was immensely costly for a single EU state, and politically unpopular in a period of rising xenophobia. Mare Nostrum was superseded by the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, Frontex, which implemented Operation Triton. The focus of Operation Triton was less on search and rescue than on border protection – the prevention of boats leaving African coasts. For the purpose of containing migration, the Italian state pays tens of millions of euros to leaders in Libya and Sudan accused of massive crimes against humanity, and it is currently collaborating with armed militias that previously trafficked migrants across the water and now work to keep them from leaving the coast with Italian support. The EU’s willingness to spend money on collaboration with armed militias and corrupt governments “elsewhere” while knowingly allowing migrants to remain detained or to drown at sea signals an explicit divestment of its responsibilities toward human rights.

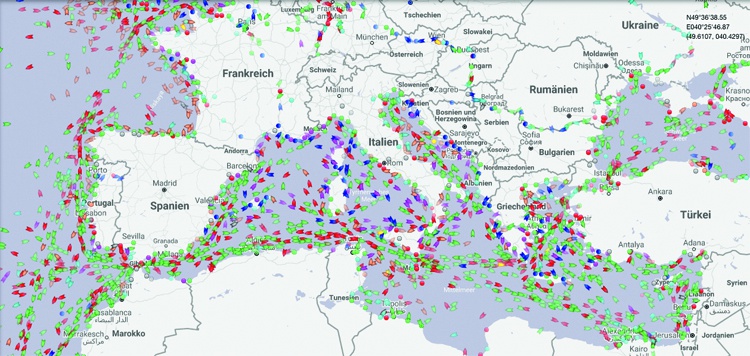

The co-founders of the Watch the Med project (a participatory online map that documents deaths and violations of migrants’ rights at sea) Charles Heller and Lorenzo Pezzani’s 18-minute film essay Liquid Traces: The Left-to-Die Boat Case (2015) demystifies the opacity of the Mediterranean Sea as liquid killer, exposing a selective and militarized mobility regime composed of multiple actors who resist responsibility for assisting migrant vessels in distress, often leaving migrants to die in plain view. [3] The video shows a digital map of the Mediterranean, the surface of the water swirling in the pattern of its currents. The black background on which it sits represents land, which foregrounds water as territory – positive space – rather than a mysterious expanse beyond the coasts. Assembling digital data from multiple surveillance technologies and comparing it with the testimony of survivors, the film reconstructs the trajectory of a migrant vessel famously left to float without assistance for 13 days in 2011. It charts its context starting with the Tunisian Civil War. Frontex responded to Tunisian unrest by increasing its presence in the area, deploying boats and aircraft to create a “mobile and deterritorialized border.” Soon afterward, civil war broke out in Libya, and within weeks, an international coalition “with the stated aim of preventing the loss of civilians” began a military intervention. NATO took over the arms embargo and declared a maritime surveillance area off the borders of Tunisia and Libya. NATO employed a fleet of war ships, maritime patrol aircraft, and, as the voiceover recounts,

“a complex assemblage of remote sensing technologies to detect threats hidden within maritime traffic. These included AIS vessel tracking systems which emit a signal to coastal radar stations with information as to the identity, speed, and position of large commercial vessels. While the AIS coverage was limited off the Libyan coast, NATO also relied on synthetic aperture radar imagery, which emits radar signals from satellites snapping the surface of the Earth according to their orbit. The returns of large vessels appear as bright pixels on the sea’s dark surface. Through such technologies, the sea’s liquid waves are supplemented by a constantly pulsating sea of electromagnetic waves.” [4]

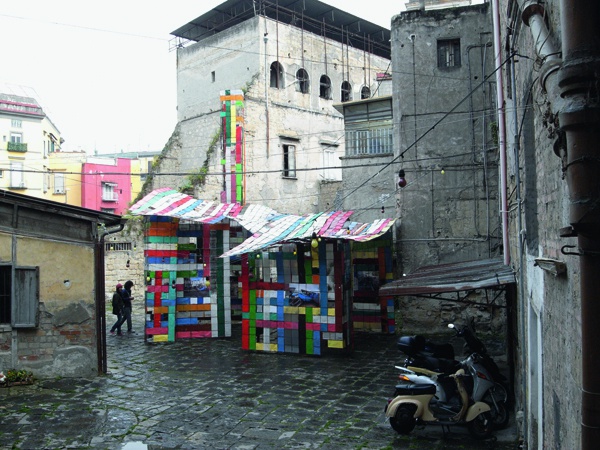

Thomas Kilpper, „A Lighthouse for Lampedusa!“, 2010

Migration increased as violence intensified in both nations and on their borders, leading to a record number of deaths at sea under NATO’s digital gaze. One ten-meter-long boat took off from the Libyan coast on March 27, 2011. This is the boat whose trajectory Liquid Traces charts with a white line on the blue water, surrounded by a moving body of bright pixels representing neighboring vessels.

Passengers on the boat were able to communicate their location to the Italian Coast Guard. The Italian Coast Guard, the Maltese Coast Guard, NATO, and every commercial and fishing vessel in the Sicilian channel received a signal every four hours for several days, and no actors responded, though the signal continued to be sent out for the next ten days. The boat floated without fuel, positioned inside NATO’s maritime surveillance area, just outside of the area in which Italy and Malta are responsible for search and rescue. Over the course of 13 days, this migrant vessel twice encountered what is believed to be a NATO helicopter. The first time, it photographed the boat and left, behavior consistent with -NATO’s policy of vessel identification and minimal assistance in cases of migrant distress. Days later, what appeared to be the same helicopter hovered over them and dropped eight bottles of water and some biscuits. Reluctant to face accusations of illegal activity, fisherman’s boats abandoned the vessel, often sailing away fast enough to almost capsize the boat. One Tunisian fishing boat told them they were four hours away from Lampedusa but did not go further to help them. None of the commercial vessels accounted for by AIS data diverted their course to rescue passengers in distress, as is their duty. The vessels recorded nearby, which included several military boats, were within two hours of the migrant vessel. By the time half the passengers on the boat were dead and the rest were drinking sea water and their own urine, they encountered a military vessel. Despite witnessing their suffering, the vessel made a rotation around the boat, taking several pictures, and left without offering any assistance. “In so doing, it murdered them without touching their bodies,” states the voiceover. “While these remote sensing technologies are usually used for surveillance, they are here repurposed as evidence of guilt.” The boat washed ashore in Zliten, Libya with only eleven passengers alive. One woman died on the beach, and another man died in prison, as the survivors were incarcerated for five days upon reaching the Libyan shore. Despite various efforts, none of these actors faced legal consequences for neglect, or for murder. [5]

This is the invisible hand of the border regime left outside of mainstream media narratives of the migration crisis. These reports have become routine fodder for discussion about Southern European politics and the future of the EU. We must look no further than the controversial case around the U. Diciotti, which has dominated Italian political discourse throughout Italian Deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini’s tenure, to see how illegal human rights violations quickly become the political norm. On August 16, 2018, Salvini prevented the docking of an Italian Coast Guard boat, the U. Diciotti, on the Italian coast after it had saved 177 migrants, mostly from Eritrea, in international waters near the coast of Malta. Malta refused to take responsibility and is not authorized to receive Italian Coast Guard boats, so the Diciotti attempted to dock in Catania. It had to anchor and remain on the water with all of its passengers because Salvini ordered that the migrants not to be allowed to disembark until other countries took responsibility for their asylum processing. The ship stood for five days before they were allowed to disembark. Salvini’s order constituted a violation of international law on human rights and of the Italian Constitution, which enshrines the right to personal liberty. [6] His order sparked calls for a trial charging him with kidnapping. However, when the Senate met to decide whether he would go to trial, 232 senators voted to protect Salvini’s parliamentary immunity, claiming that any choice he made was representative of the entire government’s decision in the interest of the Italian people. He has since closed waters to NGO rescue vessels and has stranded many boats at sea, prompting several other neighboring countries to follow suit. [7]

Thomas Kilpper, Britisches Kriegsschiff im Hafen von Mytilini auf Lesbos als Antwort auf die Migrationsbewegungen von Afrika nach Europa / British warship in the harbor of Mytilini on Lesbos. in response the migratory movements from Africa to Europe, 2017

Italian, Maltese, and Greek officials have launched criminal investigations against small charities that attempt rescue missions on the Mediterranean, often impeding their boats. In January 2019, the Sea-Watch 3, a rescue ship run by a small German charity, was ignored or refused for two weeks until Malta agreed to take in the ship and those aboard. News that was once harrowing has now been normalized as common practice. These are only some of the strategies that have brought migration down to 10% of what it was in 2015, allowing for the claim that the migration crisis is “resolved.” [8] The consequences are myriad, the two most obvious being that huge numbers of people fleeing civil war, persecution, climate change, and poverty are being detained in abusive conditions or are drowning in the Mediterranean. Human trafficking rings and detention centers on both sides of the Mediterranean continue to commit human rights violations that go unnoticed and unrecorded. The sources of civil war and unrest that prompted the wave of migration since 2014 have not abated, but reporting from the European point of view celebrates the massive drop in arrivals and fuels Salvini and other anti-immigrant leaders’ popularity.

In the early years of the migration crisis, some European countries, Germany in particular, took in many refugees, relaxed policies for asylum seekers who had crossed into them illegally, and sometimes refused to send asylum seekers back to Italy or Greece, where reception conditions were allegedly in violation of human rights law. Since then, compelled by the results, they have applied Berlusconian logic to reducing migration in Europe. Member of the Italian Coast Guard are training the Libyan Coast Guard. Libyan armed militias are collaborating with the Italian government to keep migrants on shore and detain them, rather than allowing any boats into the water, in a deal that sees “vehicles, boats and salaries in exchange for cooperation,” The New York Times reports. [9] “But the ministers also agreed to new funding for United Nations programs to help the estimated 400,000 migrants stranded in Libya, many of whom are being kept in filthy detention centers where abuse and exploitation are rife. The International Organization for Migration has documented cases of enslavement in some places, while Doctors Without Borders recently decried in an open letter the awful condition in the camps.” [10] In short, Europe is happy to throw money at the problem, and at the criticism of the problem. Turning a blind eye to continued human rights abuses and the plight of asylum seekers is a superior solution to more collaborative structures in the management of refugees. The policies suggest that once migrants are out of sight and off the Mediterranean horizon, they are out of mind, returning its blue waters back to neutral liquid without political bifurcations across its surface or a graveyard on its floor.

Title Image: Screenshot of marinetraffic.com

Notes

| [1] | Hakim Abderrezak, “The Mediterranean Seametery and Cementery in Leïla Kilani’s and Tariqu Teguia’s Filmic Works”, in: Yasser Elhariry/Edwige Tamalet Talbayev (eds.), Critically Mediterranean: Temporalities, Aesthetics, and Deployments of a Sea in Crisis (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), p. 152. |

| [2] | IOM Counts 3,771 Migrant Fatalities in -Mediterranean in 2015, https://www.iom.int/news/iom-counts-3771-migrant-fatalities-mediterranean-2015. |

| [3] | Anna Momigliano, “Italian Forces Ignored a Sinking Ship Full of Syrian Refugees and Let More Than 250 Drown, Says Leaked Audio”, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2017/05/09/italian-forces-ignored-a-sinking-ship-full-of-syrian-refugees-and-let-more-than-250-drown-says-leaked-audio/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.354610d94fae. |

| [4] | Charles Heller, Liquid Traces: “The Left-to-Die Boat” Case. |

| [5] | Heller, Liquid Traces. |

| [6] | Massimo Frigo, “The Kafkaesque ‘Diciotti’ Case in Italy: Does Keeping 177 People on a Boat Amount to an Arbitrary Deprivation of Liberty?”, http://opiniojuris.org/2018/08/28/the-kafkaesque-diciotti-case-in-italy-does-keeping-177-people-on-a-boat-amount-to-an-arbitrary-deprivation-of-liberty/. |

| [7] | Lorenzo Tondo, “Italian Senate Blocks Criminal Case against Matteo Salvini,” https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/mar/20/italian-senate-blocks-criminal-case-against-matteo-salvini. |

| [8] | European Commission Press Release “The European Agenda on Migration: EU Needs to Sustain Progress Made over the Past 4 Years,” http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-19-1496_en.htm. |

| [9] | Declan Walsh/Jason Horowitz, “Italy, Going It Alone, Stalls the Flow of Migrants. But at What Cost?” https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/17/world/europe/italy-libya-migrant-crisis.html?module=inline. |

| [10] | Walsh/Horowitz, “Italy, Going It Alone, Stalls the Flow of Migrants. But at What Cost?” |