Six Reflections on Algorithms During a Pandemic

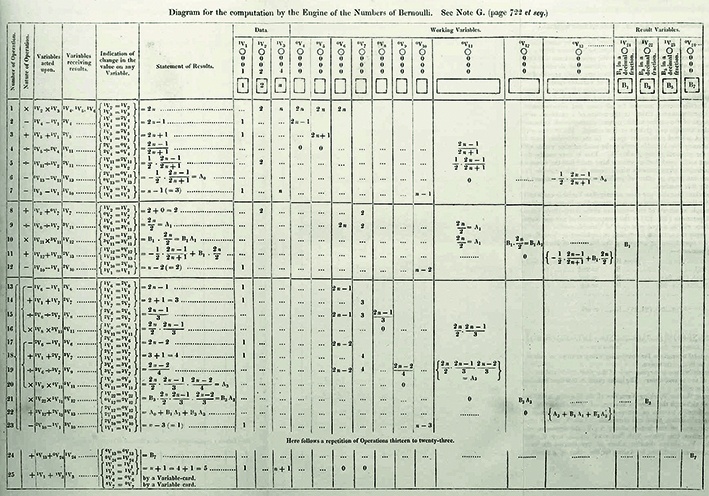

Ada Lovelace, Bernoulli-Diagramm, 1842

1

I had a dream in which Zoom was a person, and he was interviewing me. He said he considered himself an ally, even if others didn’t see him that way. I didn’t comment. He was interviewing each of us users, box by box. Mostly we were all about the same, he said. Years ago, a collaborator and I made an app that would analyze your video call conversation and give real-time directions to fit into the conversation, like be more assertive or you’re talking too much. It was intended as a critique of ever-expanding video surveillance and the use of big data for social control. Now I see this functionality built into consumer apps for next-level productivity, and it’s hardly surprising. Like many other artists, I’ve had to question the value of this sort of critique. And yet, here on endless hours of Zoom, I find myself wishing for the prompts of that earlier app, so I can check out completely into autoreply. Trying to find a sense of identity among all the boxes, I keep changing my virtual background to photos I have taken while peering into other people’s homes.

2

I have a large collection of these images because I have spent the past couple years trying to replace Amazon Alexa with myself. People around the world sign up to get ‘Lauren’ in their homes, and the process begins with an installation of a series of custom networked devices that include cameras, microphones, switches, door locks, faucets, and other appliances. For days, I remotely watch over each person 24 hours a day, controlling all aspects of their home. I attempt to be better than an AI, understanding them as a person and taking action in anticipation of their needs and desires. Sometimes this means following them from room to room, turning on lights ahead of their steps. Other times, their needs are more unique, and I order special deliveries to their home or orchestrate the ambiance of a date night. As an Alexa replacement, I speak to the inhabitants with a text-to-speech voice, and they relate to me as an AI. These are some of the things they have asked me:

Can you give me a recipe for laksa?Will you force me to go outside once a day?Can you make me more organized?Will you find me some matches on Tinder?Can you find me a new job?Can you remind me whether I took my medication?Do you like being here?Can you help me sleep with my date?Why do I feel even more alone now?Please read me stories until I fall asleep.

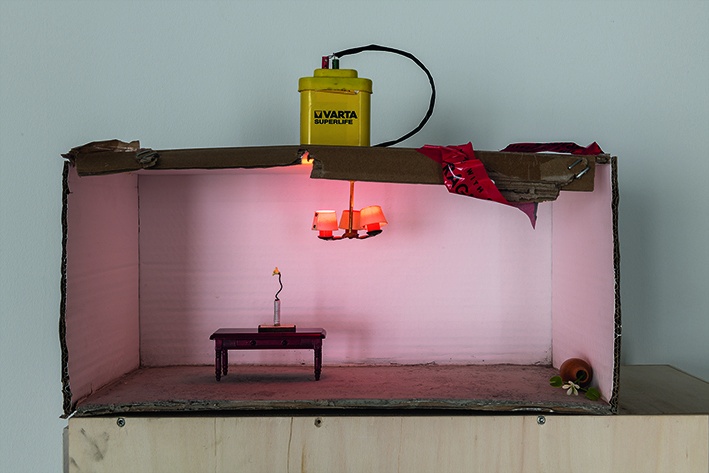

Jesse Darling, „Votive/Apologia (for & after Julie Becker)“, 2020

3

Watching people in their homes used to fascinate me, but now the thought of doing this voluntarily is unfathomable. I used to like the internet. I spend hours in this grid of homes, my brain unable to piece together so many different people in different places. It feels as though all of us are nowhere, none of us exist. I haven’t felt this simultaneously socially inundated and alone since I hosted a party that went on for 24 hours while an algorithm directed me via earpiece. As new guests cycled in every five minutes, the software would tell me what to say, who to introduce to whom, and what to do. I provided the emotional interface for the algorithm, delivering the lines as the human host for its intelligence. Guests arrived one after another, blurring together. Over the 24 hours, the algorithm carried on tirelessly, while I slowly broke down. My only distinct memory is the man that arrived and said, something you should know is that I have a lot of luggage. After some initial confusion, I realized he meant baggage.

4

Algorithms seem to be the key to health right now. But the US lacks the tools for collecting the necessary data, to understand who is infected. Tech companies come to the rescue with the troves of our data they’ve been hoarding. What does it mean that they have all this? No time to worry. Will an app tell us if it’s safe to get on a bus, or hug a friend, or automatically report us when we come within six feet of another person? For years now I’ve felt a growing awareness of being tracked. Reduced to a set of data points, I wish for anonymity, yet my desire to be seen has never been stronger. I know I’m not alone in this. I offer a small app-based service in which I physically follow people, locating them via the GPS data their phones broadcast to me, then keeping them within my sight all day. People sign up to download this app, and explain their reasons for wanting to be followed:

I want to feel less alone.I want to tell a story with no words.I think you’ll enjoy me.I have no life other than the one I lead online.I want someone to see me at my best.Nobody reads my blog.

Of course, requesting a follower points to the privilege of not feeling subject to constant surveillance already due to your appearance or identity. It is easy to see these different positions as we look at who is out on the street now, who the frontline essential workers are. Medical experts are busy working on the algorithms to determine who doctors should prioritize when equipment runs out. These, devastatingly and unsurprisingly, cut along race and class lines. What does it mean to make art in the midst of this? What is essential to get out right now?

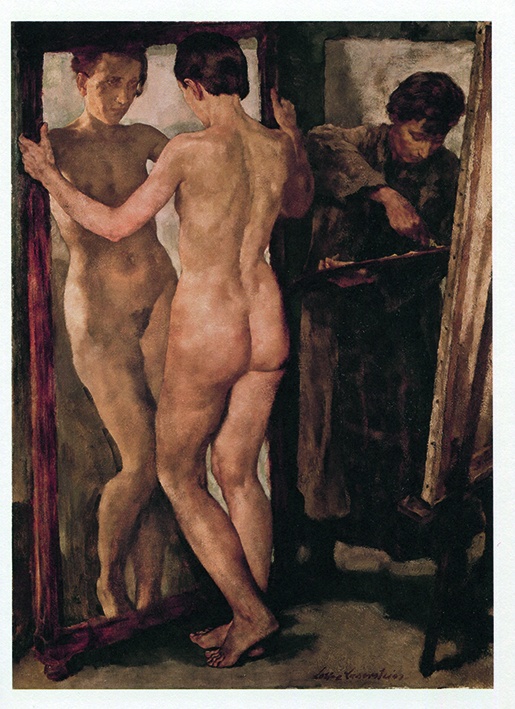

Lotte Laserstein, „Vor dem Spiegel“, 1930–31

5

I have been obsessed lately with getting parts of myself into other people’s bodies, or vice versa. The urge is especially strong now. My birthday is next week and I’ve scheduled an appointment to donate blood. I was relieved to find that I passed the self-screening process easily. I haven’t lived for a cumulative five years in Europe since 1980, and I’m not a male that has had sex with another male in the past 12 months. It was nothing compared to the process of trying to donate my eggs, which involved a 47-page questionnaire before my photos could even make it into their database of donors. Questions I answered included:

What are your favorite things to eat for breakfast?What was your least favorite subject in elementary school?Which person alive or dead do you admire most?What is your favorite band?What are your goals?Do you want the child to be able to learn your identity?

This last one didn’t really matter, no need to limit my chances, the doctor told me, because the kid would likely be able to find me in the future anyway. Just as new cohorts of donor-sperm siblings reunite on 23andMe each Christmas after receiving the kits as gifts from unknowing relatives. In the end, my data made it into the donorbase, but nobody has selected my genetic material. I’m too old to have a chance, I think, despite the doctor telling me my eggs would be doubly in demand because they could go to either a white or Asian family while still passing. None of these donations are happening now – they are are all ‘nonessential,’ as is abortion in some states. International parents awaiting children from surrogates in the United States are not able to travel to pick them up, and questions arise about who should care for these babies now. I’m thinking of all the frozen eggs that will stay that way, potential children literally frozen in time. I wonder what these empty pauses do to our understanding of our origin stories. You were supposed to be born in 2020 but we had you two years later. You would’ve been ten by now, but instead you’re eight.

Helga Wretman, „Fitness for Artists TV“ mit Hanne Lippard, 2015, Filmstill

6

As we wait in These Uncertain Times – but weren’t things always this way? – I keep thinking about how ‘later’ has taken on new importance. It has been elevated from that place to which we’d relegate anything that did not really concern us to a place where we’ll do everything. I’ve been having a series of online chats with people where we make plans for a ‘later date,’ when we are able to go outside again. I’ve been fantasizing about these later dates. Being in the same space as other people. Reaching out and touching. Shared surfaces. Breathing, talking, anything really. It is a performance in two parts. In the first, we chat and imagine together our first meeting. Where will we go, what will we do, what will we say? This future plan gets saved as a sort of script. One day, when we are allowed out again, they’ll receive a request to meet and we’ll enact this script. This will be part two. In these conversations, there’s a sense of constant recalibration. We talk about the moments as things were just shutting down, when each person’s sense of personal boundaries shifted hour to hour as we began to see each other as threats. We make tentative extremely specific plans, subject to change. Which season will it be? Will we feel any closer after all this? Will we be allowed to embrace? Most people I talk to, in every country, want to meet at the beach. But one woman proposed I accompany her to the dentist.