“NO ONE BECOMES HERSELF ALONE” ON KATE KIRKPATRICK’S “BECOMING BEAUVOIR: A LIFE”

Isabelle Graw on Kate Kirkpatrick’s “Becoming Beauvoir: A Life,” screenshot

While I thought myself familiar with Simone de Beauvoir’s life and work, it took this informed and fluently written biography by Kate Kirkpatrick to open my eyes to Beauvoir’s achievements as a philosopher. In it, the author makes a programmatic (and entirely successful) attempt to dispel Jean-Paul Sartre from the center of reception of Beauvoir’s work. For instead of once again reducing Beauvoir to a sort of philosophical echo of Sartre, as occurred in many obituaries for her that were published in France, Kirkpatrick instead traces the ethics of existentialism primarily back to Beauvoir herself. Her concept of freedom, for example, was far more complex than Sartre’s own: while he, in the 1930s, still assumed humans to be free, Beauvoir’s thoughts were at that time already circling around the tension between freedom and constraint. Confronted, as a woman, with considerable limitations to her own freedom, she realized that not every person has the power to make a free decision. Unlike Sartre’s assumption of human freedom as boundless, Beauvoir saw its measure as dependent on “contingent and unchosen things” such as “the time or place in which you were born, the colour of your skin, your sex, your family, your education, your body.” [1] Freedom can therefore only be achieved to the extent that one is able to transcend limiting factors such as gender, race, and class. One could add to this rather liberal notion of freedom that to freely transcend established societal roles in this way is still today barely possible without corresponding state measures (such as quotas or affirmative action).

Beauvoir’s notion of a conditional freedom seems to me at first glance to be of timely relevance, especially in view of the overly simplistic definition of freedom held by today’s coronavirus deniers who refuse to wear masks. For it is insufficient, following Beauvoir, to simply demand freedom for oneself; on the contrary, our striving for freedom must aim to make it possible for others to exercise their own freedom in an ethical manner. My freedom would, then, always also be that of others, and therefore naturally end at the point where its realization endangers, disadvantages, or discriminates against them.

Beauvoir’s concept of freedom is closely connected to her conception of the “self,” as Kirkpatrick comprehensively demonstrates. While we experience our “self” as our own, Beauvoir argued, at the same time it remains a product of what others make of it. And so it is that in Beauvoir’s work we see a lesson from psychoanalysis repeated, namely that a high degree of heteronomy resonates within our “self.” It can therefore in no way be said to be original, authentic, or even an essence. However, what we can do is attempt, like Beauvoir, to negotiate as much self-determination as is possible under this condition of heteronomy. Kirkpatrick demonstrates that Beauvoir sees our “selves” as fundamentally formed by and related to others using the example of her early philosophical novels, such as She Came to Stay (first published in 1943), in which the characters always live and suffer in relation to others.

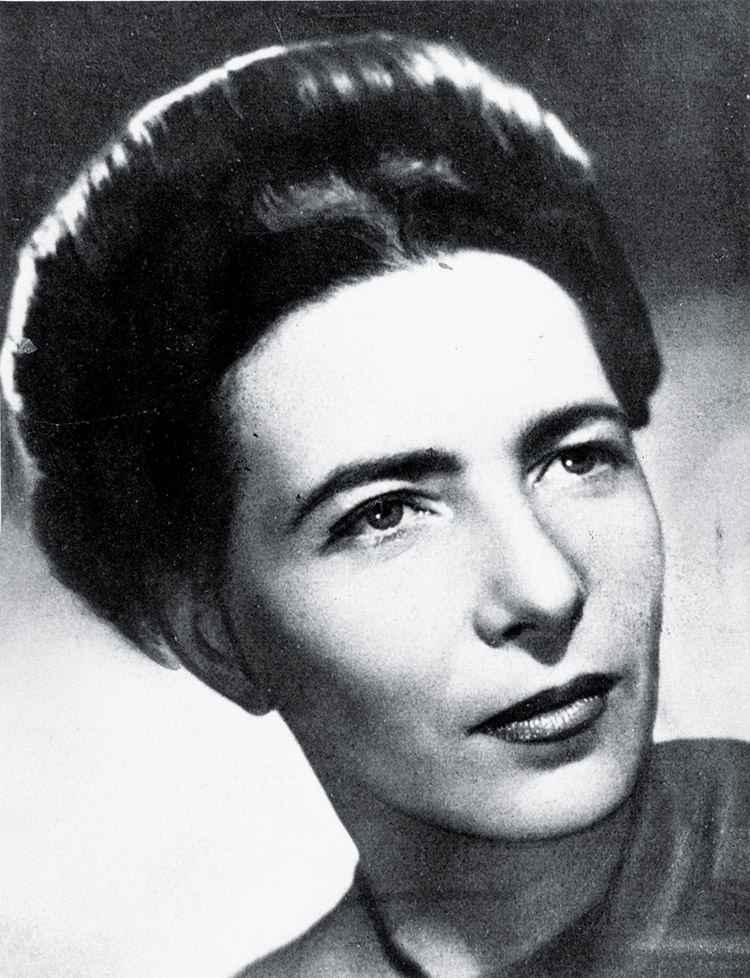

Simone de Beauvoir

Beyond this, what makes this biography of Beauvoir so relevant and worth reading is Kirkpatrick’s great sensitivity for those subtle acts of denigration and discrimination to which intellectual women still see themselves subjected today. Beauvoir’s philosophical essays, for example, would often be criticized for their supposedly immoderate tone – an accusation that, as Kirkpatrick rightly points out, was never made toward male philosophers of that time. Kirkpatrick also mentions that intellectual women such as Beauvoir tend to be particularly hard on their own work; Beauvoir herself would always downplay positive reviews of her work while fixating on the negative. In my observation, this readiness to devalue one’s own work is still extremely prevalent among the female authors of today. One is never good enough and, in a kind of internalized misogyny, “punishes” oneself for (supposed) inadequacy.

Kirkpatrick also lays open the weak points in Beauvoir’s life and work, including in her relationship to Sartre, towards whom, Kirkpatrick claims, she was far too uncritical. While Beauvoir deplored the absence of any “real reciprocity” in their relationship, she never distanced herself from him. I myself think Beauvoir stuck by Sartre for reasons beyond friendly solidarity alone; after all, ending their relationship would have put her entire living and working arrangements in danger. Kirkpatrick also points to the blind spots in Beauvoir’s feminist opus The Second Sex (first published in 1949), which she describes as being formulated “in heteronormative terms,” with Beauvoir presuming heterosexuality to be the norm. However, Kirkpatrick identifies the unabated achievement of Beauvoir’s book as its social explanation of women’s inferior status, relating it to their insufficient access to education, money, and professional opportunities. That Beauvoir’s feminism was not thought out in intersectional terms – it ignored the situation of black women, for example – is a further deficit, but one that Kirkpatrick does not elaborate on in any detail. bell hooks has reminded us in another context that the freedom demanded by white, privileged women for themselves was and is often dependent on the economic exploitation of poor and black women. [2]

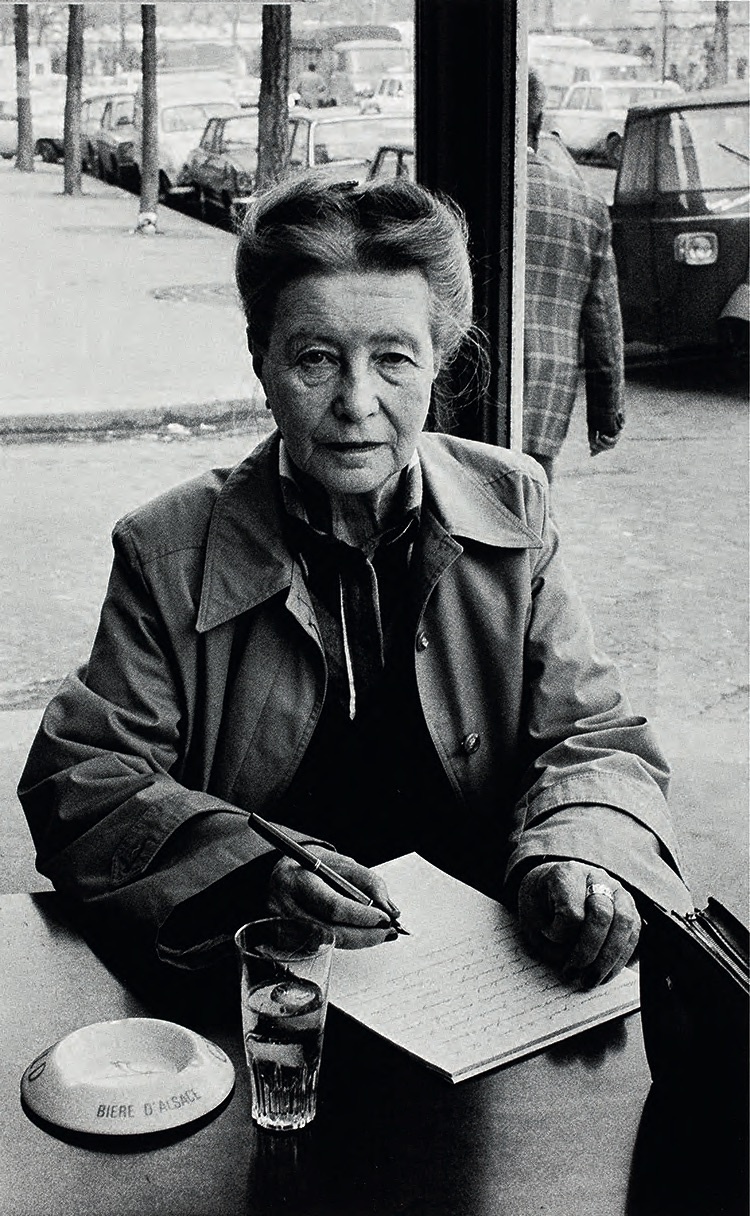

Simone de Beauvoir

In my view, however, the justified criticism of the blind spots of The Second Sex overlooks the fact that what we call “intersectional feminism” today wasn’t yet explicitly available at the time. Its shortcomings, in other words, should not prevent us from also recognizing its lasting achievements. It developed a wider social awareness of misogyny for the first time ever, for example. And some of Beauvoir’s demands are still compatible with those of today, such as her insistence, as mentioned by Kirkpatrick, that equality of the sexes concerns men and women alike – a message with significant contemporary relevance, when questions of equality within universities are regularly delegated to the women who work in them. Kirkpatrick also gives an extensive account of Beauvoir’s feminist activism in the 1970s, which included her affiliation with a pro-abortion manifesto published in Le Nouvel Observateur, at a time when the word abortion was an absolute taboo that could never appear in public life. Beauvoir’s feminist engagement went so far that she even established a column in the journal Les Temps Modernes, of which she was a coeditor; titled “Everyday Sexism,” it offered women a place to report on their personal experiences of sexism.

In summary, Kirkpatrick’s biography of Beauvoir represents a successful attempt to correlate her protagonist’s life and work with each other in a non-reductive way – that is, without reducing Beauvoir’s work to her life, as happens all too often with female authors. Instead, Beauvoir’s philosophical system is conveyed to us by carefully pointing out the ideas that were at stake in each of her novels, essays, and autobiographical works. But in doing so, Kirkpatrick never loses sight of the way in which the constraints of a patriarchal society also pervaded Beauvoir’s life and work. That Beauvoir continued to write assiduously despite the misogynistic reception of her works is also surely partly due to the continuous support of Sartre, who supported and encouraged her in all her projects. As Beauvoir’s intellectual counterpart and unconditional supporter, Sartre certainly played a central role in her life, as Kirkpatrick’s book makes clear. At the same time, however, it is also the first account of her life and work to emphasize that other people and influences – from Claude Lanzmann to Sylvie le Bon – and the solidarity of the women’s movement were at least of equal importance. The great service of this book is that it embeds Beauvoir in a more complex network of relations. And since it also narrates one the many prehistories of the #MeToo movement, it can be read as a contribution to current debates. A must-read, in my opinion.

Notes

| [1] | Kate Kirkpatrick, Becoming Beauvoir: A Life (London: Bloomsbury, 2019), p. 192. Also available in German as: Simone de Beauvoir. Ein modernes Leben, trans. Erica Fischer and Christine Richter-Nilsson (München: Piper Verlag, 2020). |

| [2] | See bell hooks, where we stand: class matters (New York: Routledge, 2000), p. 106. Also available in German as: Die Bedeutung von Klasse. Warum die Verhältnisse nicht auf Rassismus und Sexismus zu reduzieren sind, trans. Jessica Yawa Agoku (Münster: Unrast, 2020). |