SOAKED IN DIVERSITY WITH NO ROOM FOR CHANGE Karina Griffith on “Saturation: Race, Art, and the Circulation of Value”

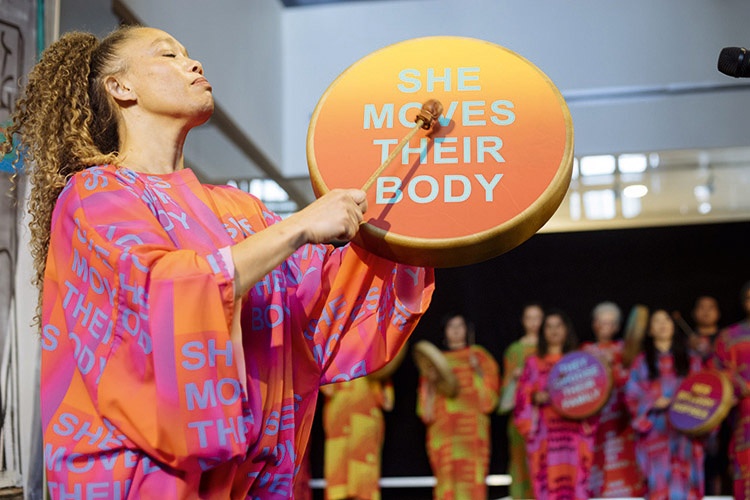

Jeffrey Gibson, “To Name An Other,” 2019

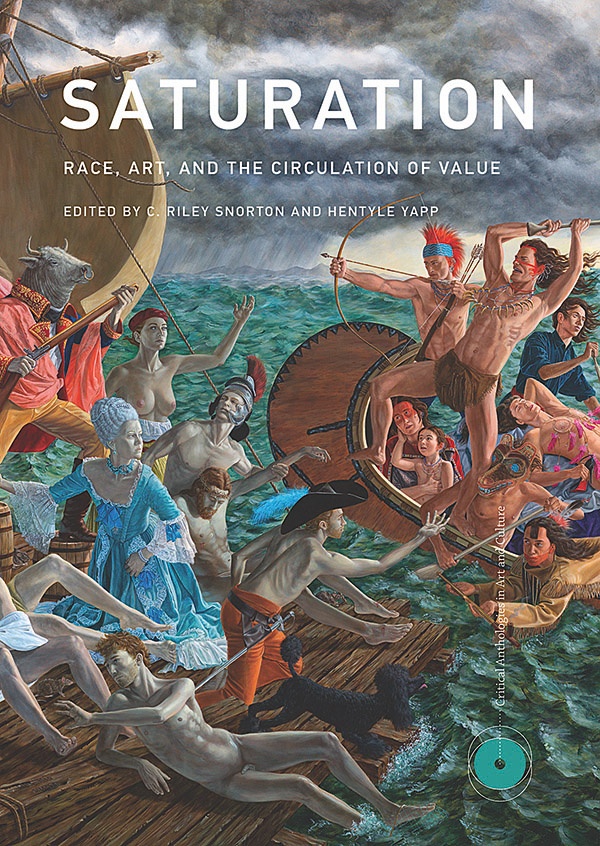

Saturation is an ambitious edited volume that takes art institutions’ liberalism and obsession with representation politics to task. Edited by C. Riley Snorton and Hentyle Yapp with contributions from Sarah Schulman, Lisa Lowe, Byron Kim, Gayatri Gopinath, Tina Takemoto, Mark Rifkin, and Hortense J. Spillers, among others, the rich compendium consists of statements from artists, new scholarly texts, and reprints of earlier works that tackle questions of institutional complicity in structural inequalities. These inequalities result in a discriminatory distribution of resources in the arts. The hefty tome is part of the New Museum’s series Critical Anthologies in Art and Culture, a project that stems from earlier collaborations with the MIT Press.

In terms of color theory, “saturation” refers to intensity of a color, which is defined in relation to how much it differs from white. Audio saturation, in turn, is a subtle form of distortion that sounds good to the human ear; it is readily accepted and does not provoke unrest, but rather harmony. The contributors to this book consider representation politics, or the practice of showing diversity without structural change, akin to the effect of this second type of saturation. Snorton and Yapp use this metaphor to frame the situation in art institutions where the typical application of diversity gives the impression of change while, in reality, masking the centrality of whiteness and ableism in operation. [1] The first of the book’s two sections, “The Saturation of Institutional Life: Race, Globality, and the Art Market,” tackles the history of racial difference. The second section, “Methods of Racial Matter and Saturation Points,” discusses practices of disentangling differences from representation.

Two significant Black feminist texts bookend the volume. In the first essay, “Racial Capitalism’s Gendered Fabric,” Sarah Haley pushes the understanding of “racial capital” (a postcolonial application of Karl Marx to think through redistribution and exchange on the level of the social construction of race) to include the complexities of gender. Picking up where Cedric J. Robinson’s book Black Marxism (1983/2000) left off, Haley unpacks the historical double-bind of Black domestic and reproductive labor. She cites Hortense Spillers’s concept of “ungendering” to address how historical accounts of slavery and oppression omit the specificity of Black women’s struggles and, in doing so, reproduce the idea of non-value. Spillers is the author of the book’s final text, “Interstices: A Small Drama of Words,” a reprint of a speech presented at Barnard College in 1982. The contribution begins with an epigraph – Audre Lorde’s poem “Who Said It Was Simple?” In the context of this book, one cannot help but think of the gendered, racial capital of Lorde quotes in contemporary territorial debates around intersectionality. In the text, Spillers addresses the state of feminist publishing in the United States and the synecdochic relationship white women have to all women. Her term “metonymic playfulness” refers to a part of the population with the resources, connections, and capital to speak for the whole. In this constellation, there is no room for Black women, much less their sexuality and bodies (a contemporary example of this would be the need for the Black Trans Lives Matter and #SayHerName movements to offset the reductive assumption that Black lives only imply heterosexual males). Spillers calls for a “heightened self-consciousness” on the part of feminist scholars to create space for the “dialectics of a global new woman,” where women of color can claim their voices in their own empowered non-fiction.

Saturation is filled with evocative neologisms and revisions to established terminology. Jasmine Elizabeth Johnson coins “hush acts” to explore how Black artists perform softness both visually and sonically to code Black anger in palpable and powerful ways in her essay “‘Sheer Pleasure’: Eloise Greenfield, Solange Knowles, and Black Hush.” Kandice Chuh explores her irritation with the concept of “aboutness” in her essay “It’s Not About Anything.” She candidly critiques the hostile, racist, and limiting questions often posed in academia to police the art canon: “What is Asian American literature about? Or, in perhaps more skeptical and sometimes aggressive form, What is Asian American/queer/black/feminist/brown about that piece of writing, music, criticism?” [2]

Kent Monkman’s painting Miss Chief’s Wet Dream (2018) on the book’s cover foreshadows the sumptuous color reproductions within: works of Cauleen Smith, Mohamed Hafez, Kara Walker, and others are a visual treat to complement the texts. The book also features artist portfolios explicitly produced for the volume, such as Lorraine O’Grady’s Diptych Portfolio (2019) and Jeffrey Gibson’s series To Name An Other (2018–19). The volume contains astute analyses of painting on a formal level, such as Marci Kwon’s reading, in her contribution to the roundtable discussion “Institutionalizing Methods: Art History and Performance and Visual Studies,” of Kerry James Marshall’s use of color in his 2009 untitled painting of a dark-skinned woman holding a palette in front of a paint-by-numbers canvas. However, regarding film and moving image, engagement remains on a level of content, and few attempts are made at more in-depth textual analysis. One exception can be found in the conversation between Denise Ferreira da Silva and Phanuel Antwi with C. Riley Snorton, “Toward the End of Time.” In response to Snorton’s question about historiography and race, Ferreira da Silva briefly mentions the films she made with Arjuna Neuman and the visual transitions they used to represent change.

Saturation aims to provide alternatives to “liberalism, modern humanism, and capitalism,” which leaves one wanting practical solutions. The book makes clear that diversity itself can be seen (or rather heard) as a lullaby that rocks us into submission to racist norms and the repetition of discrimination in institutional spaces. Art institutions need to question their motives when commissioning yet another anti-discrimination workshop without following up with significant structural change. The Anti-Racism Clause is a German initiative of theatre director Julia Wissert and lawyer Sonja Laaser. The clause places protections from institutions poised to discriminate directly in arts practitioners’ contracts. What if every institution that held a workshop to talk about diversity agreed to implement the clause? Such an action would acknowledge that racialized people’s contributions and leadership are not part of a trend to saturate but are the way forward.

Notes

| [1] | “White” is written here in italics to emphasize that race is a social construct, not simply a skin color. Also, on capital “B” Black, see “(R) Evolutionary Vocabulary” by Sandrine Micossé-Aikins and Sharon Dodua Otoo in their edited volume The Little Book of Big Visions: How to Be an Artist and Revolutionize the World (Münster: Edition Assemblage, 2012), p. 11. |

| [2] | Kandice Chuh, “It’s Not About Anything,” in: C. Riley Snorton/Hentyle Yapp (eds.), Saturation: Race, Art, and the Circulation of Value, (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2020), p. 175. |