THE REIFICATION OF OUR SOULS Isabelle Graw in conversation with Joseph Vogl on the coming community of netizens and the productive force of envy

Isabelle Graw im Gespräch mit / in conversation with Joseph Vogl, Screenshot

ISABELLE GRAW: The central achievement of your book Kapital und Ressentiment. Eine kurze Theorie der Gegenwart (2021), as I see it, is that it presents a meticulous historical reconstruction of the fusion between the finance and information economies. You essentially show how the informatization of financial markets went hand in hand with the financialization of information. And you also note the fatal consequences for a democratic society of this triumphant victory of the finance-economic order of power, in which platform companies like Google, Amazon, Facebook, etc. set out to control society and govern public spheres, or in which central banks effectively operate as government institutions designed to fend off democratic interventions into the economic system. You aptly characterize the financial regime as a “trans- or intergovernmental agent,” which is to say, as an agent that exists between governments and transcends them. You moreover demonstrate how market discipline came to be a guiding principle of policy and how the periodic efforts at regulation have been powerless against the platform companies’ parastatal activities. You open the book by declaring that “information of any kind” [1] is a “new source of value creation.” I myself am very interested in questions of the theory of value, and that’s in part why I wondered: Which conceptualization of value do you work with? In Marx, for example, value is not the same as price, which he understands to be the monetary expression of market value. Rather, Marx argues, value is an “objectification of human labor”: it originates in human labor and at once transmutes that labor into “abstract labor,” or to put it another way, value abstracts from labor, obscures it and makes it invisible. Since the question of value is also relevant to your reflections on the finance and information economy, I was wondering: What’s your conception of value?

JOSEPH VOGL: I think I based myself less on a distinctive conception of value than on technologies on the one hand and theories in which prices and values are closely interrelated on the other. Financial and stock markets are obviously central to my argument, and I maybe should underscore two points: On the one hand, the financial industry’s takeoff since the 1980s at the latest, and especially in the 1990s, cannot be described without the implantation of network architectures. The decisive factor was the migration of financial transactions out of stock exchanges hedged in by regulation toward over-the-counter trading, which is to say, into the unregulated shadow banking system, so that the majority of financial transactions now actually occur on the Web. The result has been a twofold problem: on the one hand, how to implant price formation mechanisms in technological terms, which is to say, under the conditions of information technology; and on the other hand, how to transform or translate theories of financial markets into information theories. The central hypothesis is that the prices formed in the markets already contain all necessary information, or in other words, they contain all appraisals by all possible actors, removing the need for an analysis of the fundamentals of value formations – of things like productivity, financial performance, cost structures, expected dividends, trade balances, equity ratios, the quality of management, business trends, or purchasing power, all of which are questions a good accountant would raise. In light of these concerns, there’s also a controversy within orthodox economics between the information-theoretical innervation of the market on the one hand and what’s called fundamental analysis on the other. Obviously, what you’ve just brought up, a Marxist perspective, would mostly belong in the register of fundamental analysis, asking: How many hours of work are required to manufacture certain consumer goods? How does something like abstract labor come into being, etc.? But what’s key in this symbiosis between finance economy and information technology, and I would like to reiterate this, is the fundamental coincidence of price formation and the representation of information.

GRAW: Reading your account of information-saturated prices in the financial market, I couldn’t help but think of parallel as well as diverging developments in the sphere of art auctions. The auction business constitutes a specific segment of the art market in which high prices are often equated, or confused, with artistic relevance. But whether the desires of those who are active in it become invested in a work of art hinges less on information such as the value judgments of experts than on what the sociologist Jens Beckert has called “fictional expectations”: the futures imagined for a work of art that lend it an appearance of lasting significance and credibility. Still, I wonder: If such projections also result in value creation in the way you’ve described – you’ve discussed “informational activities” that effectively generate value, a phrase that recalls Maurizio Lazzarato’s concept of “immaterial labor” – how exactly are those “informational activities” converted into value?

VOGL: You’ve already mentioned an essential point: that the trading activity in financial markets is described – and has been described since the early modern period – as dealing in future prospects and risks. In this light, what actually counts is a peculiar equipollence of news reports and opinions, of opinions about opinions, of assertions, rumors, etc. As a consequence, these early stock exchanges are already, to quote the title of a work by a 17th-century theorist, the scene of a “confusion of confusions.” And this confusion of confusions, I think, is crucial in that reports about events or facts have the same status as opinions or opinions about other opinions. The way I’ve described it in the book is that what we really have here is an early form of opinion markets, which function only on the condition that it’s indeed risks – risk assessments, future prospects, and evaluations of these future prospects – that become the objects of the trading activity. So in a certain sense, the difference that knowledge makes gets cancelled.

GRAW: Untethered opinion as an engine of value formation, that’s a principal observation in your book. The contrast you draw between information and knowledge, which in fact emerge as diametrical opposites, runs through your entire argument. Uncertainties and unresolved complex problems, you write, are hallmarks of knowledge. You also emphasize that knowledge follows an anti-algorithmic path, so it can’t necessarily be found online. By contradistinction, you define information as “knowledge minus demonstration and justification”: in other words, information is a kind of knowledge without the essence of knowledge – experimental test arrangements, newly identified problems, hypotheses that are substantiated, etc. Now I found myself wondering, also with a view to artistic practices that, under the banner of artistic research, want to be perceived as forms of knowledge: Can we actually draw such an unambiguous distinction between knowledge and information? After all, artistic works of this type can incorporate information, just as they can absorb knowledge and engender forms of knowledge. Should we not rather concede that information processing is also a fundamental aspect of knowledge, in other words, that “news,” “reports,” “correspondences,” “accounts,” “letters,” or mere “rumors” – the guises in which, you write, information appears – figure within knowledge as well?

VOGL: Your first question goes back to the interrelation between information technologies and financial markets, the prerequisite for the automatization of markets. We mustn’t forget that around 70 percent of financial transactions today are actually automated, which is to say, processed by algorithms. And what I would call surprisal difference – which is simply the irritation of expectations (say, by price fluctuations) – is central to technologically and algorithmically comprehensible information. This lets me perhaps answer your question with a paradox: considered in this light, information is no longer different from knowledge, while knowledge for its part can mark a difference from information. What this ultimately means is that such knowledge can’t be turned into algorithms, as you’ve mentioned, that it can’t be automated, and most importantly, that it can’t be scaled. Knowledge, in this respect, would need to be defined in procedural and processual terms, based not on an outcome, a result, an ascertained fact, but on an open research process, on open research questions, on unforeseeable avenues and trajectories. These can’t be reduplicated by automated processing; they’re processes that, we might say, consume finitude.

GRAW: Knowledge doesn’t aim at measurable results and is limited in time by the lifetime of its producers?

VOGL: To put it another way, although knowledge does aim at measurable or verifiable results, it isn’t exclusively defined by those results, by certain resultative logics. Needless to say, there should be some kind of outcome, a product, an insight, a surprising conclusion, an interpretation – but always on the condition that the ways that led there, the wrong turns and diversions, the blind alleys and fresh starts, aren’t forgotten. That process eats up the time of someone’s life, it confronts us with finitude; working on knowledge, we experience our own mortality.

GRAW: Knowledge is bounded in time by the mortality of the knowledge producers. As to your observation of an ascendancy of untethered opinion, on the one hand, I would agree – also with a view to the growing presence of opinions in seminar rooms, or to art criticism, where the prevailing gesture today is one of flat assertion, with no need for demonstration and substantiation (which is to say, knowledge practices). On the other hand, there are also noteworthy efforts being undertaken right now to integrate non-knowledge that has been marginalized by knowledge – like magical thinking, esoteric practices, and, more fundamentally, affects, all these things – into knowledge. This happens in view of the opening of knowledge toward its non-Western forms. Wouldn’t you agree that these developments call for an expansion and modification of your conception of knowledge? Or is that conception capacious enough to account for them?

VOGL: The conception of knowledge that I’ve introduced en passant isn’t one that can be defined by a commitment to a particular episteme. For example, it includes what’s called implicit knowledge, which is to say, more or less conscious practices and skills. It includes processes of making, of producing, what is called poiesis or phronesis, that is, practical wisdom and special insights, and even aesthesis, processes of sensory perception. My conception of knowledge, in other words, is not constrained by a rigorous epistemological definition but encompasses all sorts of contributions – mental, psychological, physical – to generative processes of any kind.

GRAW: You describe the financial markets as a place where this knowledge is virtually without significance: asset prices fall or rise based on information or what you call untethered opinion, “collective beliefs that have become the norm.” Such normalized collective beliefs can cause market fluctuations in the sphere of art auctions as well. At the same time, forms of art-historical and art-critical meaning production, which we would associate with knowledge, do have some influence over the formation of symbolic value – though their influence in the auction market appears to be in steep decline right now. Still, it seems to me that the distinction between information and knowledge has little purchase in this sphere.

Trevor Paglen, „They Watch the Moon“, 2010

VOGL: That may be. But allow me to clarify once again that I see this concept of information as becoming relevant primarily in conditions defined by cybernetics and information technology, as well as the theory of finance; we might in fact speak of the emergence of an information standard. As I prepared for this conversation, needless to say I also thought about where the hinges between the art market, including the auction-room dramas, and the financial markets are located. And it seems to me that speculative trades are a key point they have in common. The art market, too, is a capital market. Then again, what strikes me as a radical difference is that in the art market – perhaps with a few exceptions, like crypto art – other capital formations play a decisive role, things like symbolic capital, the investment in individuals, in styles, in trends, in schools or art-critical tendencies. This means that the art market is compelled to rely – and does rely, in identifiable ways – on a variety of formulas of social capital formation that can’t be subsumed under a narrowly defined concept of information.

GRAW: Yes. It’s true that there are phenomena, like the NFTs that everyone’s talking about right now, that show a lot of overlap with financial products and are largely independent of symbolic capital formations. But unlike financial products, many objects that circulate in the art market are typically unique physical specimens that are associated with symbolic meaning. So there’s a presumption that these objects themselves make a difference, that something emanates from them – perhaps the production of fresh insights, the elicitation of affects, a reflection on social states of affairs, or the like. And this difference, which art criticism and art history routinely claim for works of art, would seem to justify the value formation in the field and lend it an aspect of substantiality. That is to say, the value of art seems to have a basis in the art itself – and the objects also provide material footholds for this idea that their value is seemingly substantial. But in your book, when I read, say, the passage where you describe the process of price formation in the financial markets as, to quote, an “infinite mirror image without a fixed fulcrum in which everyone’s fortunes and fortune depend solely on the interpretation of what the others think,” I would say: yes, that aspect of the presumed thoughts and desires of others plays a major role in the art market as well. Only there we’re dealing with products that enact a kind of logic of their own and that seem to emanate something.

VOGL: We should leave the art market behind sooner rather than later, because I’m really on less than solid footing there. But if I may venture an off-the-cuff hypothesis: the art market, in its extended history, first evolved out of finance structures that were effectively feudal and in part defined by patronage. And then it took a leap, as it were, into price formation mechanisms that actually do resemble those of the financial and stock markets and sometimes produce results that leave one baffled – baffled by fantasy prices in the same way one is sometimes baffled by the enormous market capitalizations of some companies, startups and dot-coms, that have never yet turned a profit. So in the art market no less than in today’s financial markets, we’re encountering certain imperious displays of sublimity in which price formations can no longer be matched to tangible representations.

GRAW: Exactly, price formations are hardly plausible. At the same time, I’d say, what might be a key difference between the financial and art markets – we’ll move on in a moment – is that, as you’ve shown, financial products, unlike art products, are unencumbered by transportation and the vexations of production.

VOGL: Yes, that’s the argument in more recent theories of financial markets that are based on the efficient market hypothesis: in their account, financial markets are the perfect markets par excellence because participants in them can disregard the frictions and inertias of the physical, material world.

GRAW: Exactly. In contrast with some works of art, which, it’s worth noting, are often a hassle to ship, which may be the source of the peculiar and almost archaic inertia that enhances their fascination, especially for finance types.

VOGL: But then we should add: it’s a market that beckons with unadulterated capitalist fun, with the genuine delight of manufactured scarcity. And that, it seems, is worth any price – whatever it is that I’ve snapped up at an auction, it’s mine and mine alone and I snatched it from under everyone else’s nose. Isn’t the very act of snapping up one of the capitalist’s most profound and most heartfelt gratifications?

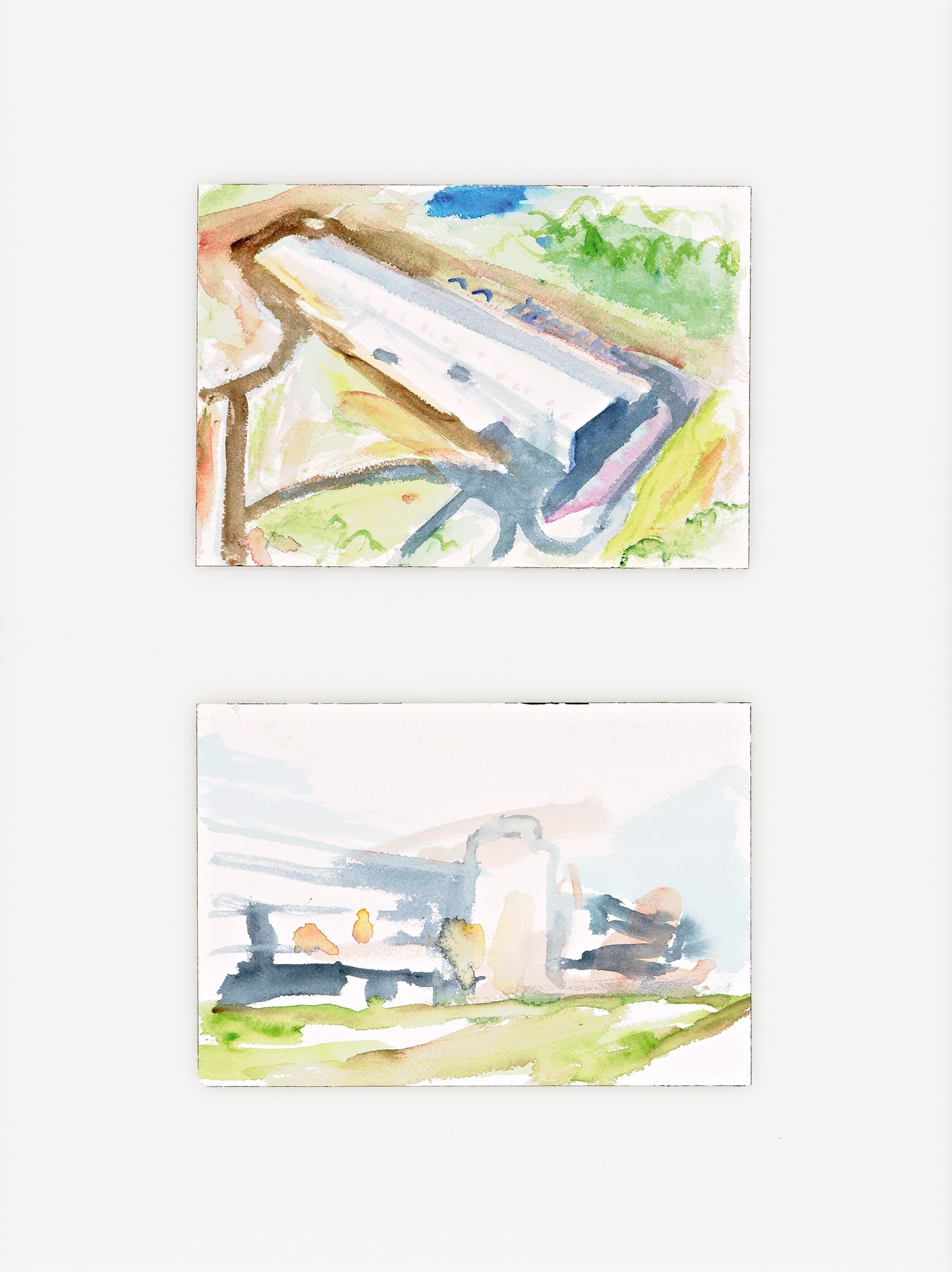

John Kelsey, „Facebook Data Center, Rutherford County, NC V. Google Data Center, The Netherlands II.“, 2013

GRAW: Yes. Owning the unique work of art is a kind of coronation, marking the owner as a singular and exceptional individual who has an edge over others, who has something they can’t have. But let’s leave it at that for the art market and turn to social media. My impression – which may be due to the culture-critical design of your study – is that you focus more on the value-creating activities of users and less on what those users themselves hope to gain from their activities. I asked myself: Why do people post nonstop? You say that social media users do it because they’re worried that they might forfeit social, economic, or professional advantages. Is voluntary incessant online posting really just an expression of a society-of-control regime that users have internalized? On the contrary, isn’t it legitimate and even understandable in some situations? For marginalized people in particular, don’t social media provide a forum not controlled by gatekeepers or experts who might prevent their voices from being heard? I would always defend expertise against populists like Trump and his ilk, but shouldn’t we nonetheless be attentive to the ways in which expertise can also imply questionable exclusions? And to my mind, this aspect – let’s call it the emancipatory potential of social media, as illustrated by, say, the #MeToo movement – is given short shrift in your book. After all, women posted their experiences of sexual harassment on Facebook and similar platforms in part because they didn’t have to fear being silenced there. True, there’s a flipside to that space of possibility – a call-out culture that opts for right-wing strategies like trolling, etc. Still, wouldn’t it make sense to explore the attraction of these platforms as well?

VOGL: You’re right, that’s a whole area I left unaddressed, and perhaps for good reason. I wanted to set aside the psychology of users, and in a certain sense I also wasn’t interested in it. To begin with, this approach let me invoke a line of argument that’s not new and that I didn’t come up with – it’s modeled by older studies such as Luc Boltanski and Ève Chiapello’s New Spirit of Capitalism – and intertwine it with the following question: To what extent do certain artistic practices, including certain emancipatory dynamics, offer no resistance to capitalist processes of exploitation that would occupy, integrate, and commercialize them? So my argument doesn’t start with the fine communicative potentials of networks, which, since the 1980s at least, have also been associated with certain promises of the decentralization of power, the democratization of the sphere of communication, etc. Rather, the point of departure for my argument is the radical privatization of public infrastructures, which is likewise attested by specific dateable events. Perhaps I need to be at least a bit specific in order to spell out the crucial point. As I see it, the mid-1990s were a sea change, maybe even an epochal threshold, spearheaded by legislative processes in the United States that established two essential new conditions for communication in networks. One was the opening of the World Wide Web to private investment. That was a momentous step for private enterprise’s occupation of public infrastructures. And the other was the creation of what we might call a liability privilege for particular companies. Specifically, since 1996, section 230 of the so-called Communications Decency Act has released internet providers from all responsibility for content published by others. These two things come together, which is why my argument engages with a radically privatized network in conjunction with liability privileges unlike anything that other kinds of companies can claim. In this situation, the rapidly expanding platform corporations, including what we call social media companies, then faced the question: How can non-rivaling goods – which is to say, goods that, like information (and unlike the beer in the bottle and the gas in the tank), are not diminished by consumption – be made scarce so that they’re good business? And the only way to achieve that is the establishment of a radical informational asymmetry, which, on the one hand, has created the possibility of a new market with a completely novel consumer character profile: we’re fed free goods, including all kinds of apps and everyday widgets, complimentary services, and other splendid digital stuff. The new type of consumer insists on these giveaways – on getting things for free. On the other hand, however, those giveaways are available only on the condition that the resource they generate – to wit, information, data, and metadata – is inaccessible to those same users. They have no control over it, must not have control over it, for the deal to work. So by the time someone or something, whoever or whatever it may be, makes a bid for emancipation on Facebook or wherever, they’ve already resigned themselves to their own digital expropriation. They should at least have the capacity for self-irony to admit as much to themselves.

GRAW: But why do users so readily put up with this digital expropriation? I’m also thinking of books like Legacy Russell’s Glitch Feminism, which demonstrates that social media do provide a forum where people can live identities that are marginalized and discriminated against in real life. And a movement like #MeToo would presumably never have happened without social media. So they do present a space of possibility, though one that’s capitalized through and through. What’s your personal experience with social media been like?

VOGL: There hasn’t been any. I don’t need it, there’s nothing appealing about it to me, brief glimpses have repelled me more than anything else. And I find the pressure to be hypercommunicative that I’m subject to as it is to be quite enough; the rest is a matter of self-protection. But I do want to raise the concern that the unquestioned expectation that private infrastructures can be used for free opens the door to forces that people will then never be rid of.

GRAW: What’s most baffling to me about it – also when I look at my fourteen-year-old daughter and her peers – is the indifference with which people view these forces they unintentionally invite into their lives. Of course, I discuss the fact with her that her data is being collected, that surplus value is being extracted from her life, that she’s being manipulated, etc. I also discuss possible forms of tracking with her. But it all leaves her completely unfazed; she defends social media as a source of alternative knowledge and forum for global networking opportunities that would otherwise elude her. I’ve also tried to explain to her that the rise of the platform corporations goes hand in hand with what you describe as the danger of a dissociation between “netizen and citizen,” and that we’re witnessing the “voluntary accession of entire populations to a private online state.” Yet these warnings appear to be impotent against the fascination and libidinal allure of social media. Why is that?

Pieter Bruegel der Ältere / the Elder, „Der Triumph des Todes / The Triumph of Death“, 1562

VOGL: But isn’t that a long-entrenched consumer behavior letting itself be awed right now by a fresh spectrum of fascinating perks? What’s interesting, I would argue, is that we’ve entered a situation in which the voluntary surrender of information for purposes of processing has become an attraction. What used to be the “ladies’ paradise,” the bliss of the department-store universe that Émile Zola captured, is now the actively engaged netizen’s right to free gratification. People strike control bargains: digital fodder in exchange for data – the users’ paradise.

GRAW: Yes, a paradise whose promises seem to eclipse its downsides. In Ten Arguments for Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now, Jaron Lanier proposed that we all cancel our social media accounts. Doing so may be a way to inflict damage on these infrastructures, but it won’t disable their ideologies and promises.

VOGL: That may well be. And one can only agree with Lanier when he says of social media: “Garbage in, garbage out.” But let’s go back to a fundamental question: What were the major innovations that allowed contemporary finance and information capitalism to create structures that make transcending or undercutting, reducing or regulating it so exceptionally difficult? That’s the situation in which we’ve arrived, and of course we can say that users’ micro-behaviors won’t change anything about this model. Nor will the actions of individual nation-states. Still, the situation we’re in is one in which reconsidering our own behavior might in fact become a question of ethos. Do we really want to keep fattening the parasites in the channels? Is it advisable to surrender all communications – the production of the social – to corporations? Is it inevitable that our last remaining means of production, our own words, are taken away from us? Must we resign ourselves to a kind of situation that Kafka once adumbrated, one in which the parasites, the phantoms that populate the conduits, “will not starve, but we will be destroyed”? Or, to be specific again, wouldn’t it be worthwhile, in purely materialist terms, to raise the question of the ownership of these means of production that we’re dealing with today, including in this conversation?

GRAW: Although I don’t believe that we will be destroyed from our user activities, you’re right: Zoom should be ours for as long as we speak! Another point I wanted to address before we conclude is the final subject of your book, the social affect of resentment, as well as a closely related emotion, envy. After all, this conversation will be part of our “Envy” issue. In what I thought was a very apt and helpful way of looking at it, you’ve described resentment as both a product and a productive force of the contemporary economic system. The same, I would argue, could be said of envy. How would you distinguish envy from resentment, where do they overlap, and in which aspects is each a very specific social affect?

VOGL: We might start by looking at the ways people talk about envy. Perhaps we might venture the hypothesis that envy is talked about before it even exists anywhere. As far back as the Church Fathers, ever since it was declared a deadly sin or cardinal vice, envy has served as a disqualifying label, referring to demands that are somehow dishonest and unjustified. That’s what’s happening today when commentators speak of “social envy.” It’s an incrimination leveled against demands raised by others that are supposedly not altogether legitimate. Such discourses of envy, whose objective is to disqualify legitimate requests for participation as thinly veiled demands for material possessions, have been a favorite exercise of liberalism in particular, a tradition that goes back to Friedrich Hayek, who labeled calls for justice as mere wallowing in envy. That would be a first point. So the argument should begin with an examination of the logic of how envy is talked about. On the other hand, envy, once it’s placed in the subject’s interior, always goes hand in hand with the observation of something we might call a “reification of the soul.” In other words, envy – and this is true across different eras – evinces an economic bias, which makes it, even in the elementary psychological configuration, a complex ensemble of relations that we can sketch as follows: envy establishes, first, a relation to others that by the same token, second, defines a relation to the self. And this relation, to self and other, at once ties in, third, with what we can call proper-ty (Eigen-schaft) in the most literal sense, something that has the form of ownership and that others are said to own, as it were.

Mark Leckey, „The Ecstasy of Always Bursting Forth“, 2013

GRAW: … or that others are imagined to possess.

VOGL: Exactly. There’s a projection involved: I lack what others have. And then there’s a fourth aspect that comes in: this relation to self and other that ties in with others’ properties – traits or possessions – is embedded in a comparative framework, bringing a calculating and measuring reason into play. So it’s an extraordinarily complex nexus of different relations. To push the argument a bit, the mere psychological reflex of envy, the configuration of a psychological interior, contains a kind of social theory that we might elaborate.

GRAW: In a structural perspective, then, envy is an intrapsychic and relational affect with a social dimension. But you’ve also noted that the insinuation – which is widespread in the cultural sector – that someone else is just envious can be a means to fend off the legitimate critique articulated by the less privileged. At the same time, I think that one thing envy and resentment might have in common is their comparative framework – both affects result from the comparative and relational pressure that is stronger than ever in a society defined by competition. Perhaps there is, in that society, which turns us into comparative creatures (Sighard Neckel), no avoiding envy – or resentment? Or are we capable of obsessively comparing ourselves to others without giving in to feelings of resentment and envy?

VOGL: I’d like to table the last point for now – maybe we can come back later to the damage that evaluative logics can do, also to the fabric of society. For now, I’d like to approach the question of resentment from a perspective of historical observation. In a first step, it’s worth recalling that the emergence of what has been called bourgeois society or perhaps also market society since the 17th and 18th centuries has been accompanied by a noticeable change in affective economies. Affective economies are characterized by circulating social energies that set individuals or subjects in motion, make them agile, mobilize them. Early social theorists and moral philosophers, for instance, noted that erstwhile cardinal sins or vices – a category that included avarice and envy as well as prodigality – once put into circulation, are actually productive in economic terms. In other words, vices are more apt than certain virtues are to develop particular ruses and stratagems – a cleverness in operating in the market. Now, as to resentment as a specific concept in the economy of morals, it’s at least worth noting that this concept takes shape in the second half of the 19th century – in writers like Nietzsche, like Tocqueville, of course, and later in Werner Sombart and Max Scheler, but in a very circumspect form, also already in Kierkegaard. They connect that resentment to the emergence of modern industrial and finance capitalism on the one hand and to what we might call competitive societies and rivalry societies on the other. And in this situation, it made sense to keep an eye on the economic implications of resentment: its market-activated side and the side that has an activating effect on certain market processes. So if you want to segue from envy to resentment – and almost all writers in fact argue that the line between them is blurry – you might say that envy as a reifying psychological configuration in individuals illustrates an atomistic social principle. Envy atomizes individuals, isolating them and linking them up in series. And I would claim that the shift to resentment effects a social organization, if you will, of this atomizing dimension of the envy reflex. In resentment, envy as an internal psychological configuration turns into a force of social structure, taking on an immediate constructive function in society.

GRAW: The study of resentment’s economic, social, and psychological premises in your book makes it read in some places like a justification of resentment. To put it another way, you seem to muster a lot of understanding for resentment as a structuring social emotion, as when you discuss, for example, how it arises due to an observed or felt gap between a promised equality of rights and factual inequality. So is resentment also a legitimate emotion when it results from this specific combination of real-life experiences of inequality with theoretical rights to equality?

VOGL: Allow me to offer a cautious objection. With Nietzsche, I would never deny the toxic dimension of that resentment; it is a poisonous snake in the moral economy. There’s a passage in my book where I’ve described everything that comes with resentment as a “conformist insurgency,” which is to say, as something that captures a domain of observations that may well be legitimate but then transforms it into a blockage of the political and social consequences bound up with those observations. One prominent example would be the escalation of anti-Semitism driven by the bull markets and crises of the late 19th-century. That anti-Semitism, which took aim at the “Jewish financial capital,” performed a mode of capitalist self-critique without touching on the structure of capitalism – it effectively became a screen obscuring the intrinsic logic of the contemporary state of affairs.

„Amalia Ulman: Performing for the Camera“, Tate Modern, London, 2016, Ausstellungsansicht / installation view

GRAW: You’ve portrayed the tendency of resentment – which it obviously shares with anti-Semitism – to insinuate that the other commands an imaginary abundance. In today’s perspective, we might add that this imagination has flourished during the pandemic; people rarely encounter the other anymore, the other whom one met face-to-face has been replaced by a phantasm. What’s more, resentment is prone to personalization: instead of analyzing social structures, it seeks relief by fixating on individuals whom it casts in the role of a “bad breast” (Melanie Klein) that must be annihilated and accordingly targets with destructive energies like hatred and vilification. Might it be that the pandemic we’re now leaving behind – or perhaps we aren’t – provides the ideal breeding ground for resentment?

VOGL: It’s presumably too early to answer that question. But it may be helpful describe the systematic locus in the production of resentment in light of capitalist market dynamics. Those dynamics essentially consist in the creation of states of scarcity: the production of scarcity is the condition for the dynamism of this market. So we can reasonably assert that the subjects that operate in these markets can inevitably always plead that someone snatched something away from them – that there’s always already someone who’s a suitable vehicle for the phantasm of jouissance. The jouissance is in the other, and what I lack is stored up in abundance where the other is. That, you might say, is the primal scene of nascent resentment. And that’s where I would once again second Nietzsche and his observation that the ruse of resentment lies in its inability to handle murky causalities, or unresolved questions of causation. It must be someone’s fault that I’m miserable. At this point, and that’s what you might call the demonic side of resentment, there’s an obsessive need for concretion, for personalization, for a guilty party to be named. It’s a position that can be filled in a variety of ways, and I think if we studied the history of resentment more closely, we could identify various dramas around whom to blame. That’s where resentment and resentment-fueled reason curdle into contentment with limited insight into the logic of the current state of affairs. Resentment is a call to intellectual self-sufficiency, encouraging people to stop asking questions and instead unleash an executory glee, a certain delight in retribution, a punitive zeal that proposes to settle a matter by sanctioning people. That’s a very abstract account, but maybe it goes some way toward illuminating the inner drama of resentment as something that structures and produces social fields.

GRAW: Your book also describes how the critique fermenting in resentment always resorts to policing: it hunts for these tangible substitute objects that can somehow be held liable, and the result – this is your book’s final conclusion, a very gloomy one, I thought – is a kind of community spirit you describe as hostility of all toward all. It’s a diagnosis that may well apply to social media: the moment someone stands out in any way, there’s the danger that everyone trains their hostility on that one individual and seeks relief by taking a swing at them. But I think that this propensity for hostility, for ganging up on people, is hardly universal, because many people on an existential level can’t afford to join in it. Many people work offline so that others can work online. What about them?

VOGL: Let me begin my answer with a prefatory remark and an explanation. To pick the most obvious example and use the peremptory term, I wouldn’t describe something like class conflict as a resentment-driven movement. That’s why I chose my words very carefully and said there must be economic reasons explaining resentment outside economic inequality. In other words, economic disadvantages can provoke outrage, if you will. But I wouldn’t use the term resentment to describe that outrage.

GRAW: Yes, the gesture of outrage has been a legitimate political articulation ever since Zola’s J’accuse.

VOGL: And the second point concerning this hostility of all toward all is an oblique quote with which I’ve called in backup, as it were. It’s from Robert Musil’s Man without Qualities and relates to his portrait of Kakania in 1913, which is to say, of a society that, in the novel’s and the narrator’s perspective, is on the eve of war. In a key passage, the narrator writes something like the following: it may well be that here in Kakania, aversion of all toward all has become a “new community spirit.” And that’s how the question of the prewar period came into play, which is of course bound up with the open question: To what extent do certain forms of communication that I was also concerned with in this book radically undermine solidarity? Even if particular identities emerge, even if there are community feedback loops, the question we face is whether the production of social schisms is integral to a logic of this communication-hacking communication, producing something that showcases hostility as the new principle of socialization – a principle that, I should note, is perfectly capable of forging an alliance or close union with competitive relations.

GRAW: So if we’re dealing with these new forms of communication that fuel hostility and undermine solidarity – now compounded by the pandemic, which has left the great majority of cultural workers with few options for offline engagement – how can we avoid being sucked in by these feelings of aversion? Given the circumstances, would you advocate something like internet abstinence or strategies of de-networking of the sort that Urs Stäheli has proposed?

VOGL: Yes, why not strategies of de-networking. One of the most radical forms, I suppose, was Walter Benjamin’s vision of the general strike, a strike that paralyzed all functional processes. And a bit more cautiously, we might ask whether and in which nodes such de-networking strategies are already emerging. One approach that’s on the canonical side appears to be through the domain of law and legislation. It’s been pretty surprising this past year to watch the European Commission, a quite liberal institution, proposing a raft of de-networking legislation that might take on a distinctly radical quality; it remains to be seen what will come of it. The proposals address concerns like European informational sovereignty, administration of the Web by a neutral trustee corporation, the prevention of data extraction, limits on the liability privileges enjoyed by internet companies, the breaking up of monopolies, etc. I think there’s a line of battle coming into view whose defining issue is the defense of the democratic rule of law. Other possible interventions that have been proposed by experts from the information and digital technology sector are about technical modifications designed to disrupt positive-feedback effects, undistorting stimulus-response chains, installing holding basins for radioactive content, inserting jamming sources, or dialing up the background noise … And these very diverse efforts should converge on a single objective: blocking the platform industry’s mechanical, social, and economic libido structure.

Translation: Gerrit Jackson

Note

| [1] | All quotations translated into English by Gerrit Jackson. |