“ART THAT LIVES”: ON COLECTIVO ACCIONES DE ARTE (CADA)

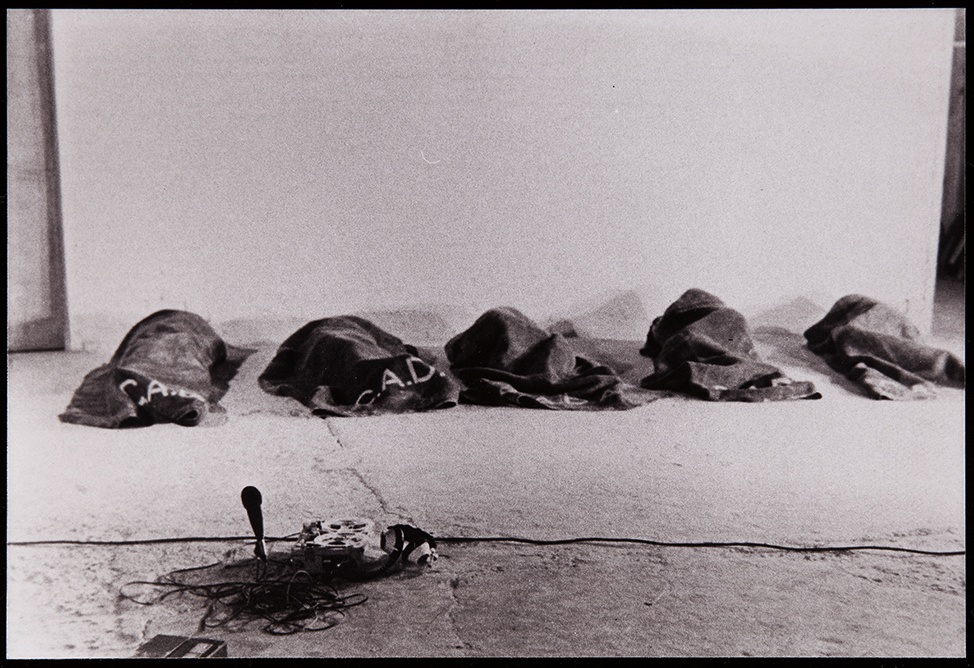

CADA (Colectivo de Acciones de Arte), „El fulgor de la huelga“, 1981

In 1979, six years after a US-backed coup in Chile ousted the democratically elected Socialist president Salvador Allende and installed the brutal dictator General Augusto Pinochet, Colectivo Acciones de Arte (CADA) took to the streets with a series of insurgent actions that commented on widespread conditions of poverty, repression, and Pinochet’s neoliberal economic policies that generated inequity. The word cada means “each” or “every” in Spanish, and CADA consisted of the visual artists Juan Castillo and Lotty Rosenfeld, the writers Diamela Eltit and Raúl Zurita, and the sociologist Fernando Balcells. The collective’s transdisciplinary constitution was foundational to its interventions, which largely took place outside of art institutions and aimed to foster critical conversations about the blurred lines between political protest and cultural practices like poetry. [1]

CADA is perhaps most well-known for projects in which it modeled and metaphorized the radical re-redistribution of resources, for example, handing out half-liters of powdered milk to residents of working-class areas around Santiago in Para no morir de hambre en el arte (So as not to die of hunger in art), in 1979 – an explicit reference to Allende’s Popular Unity promise that every child in Chile would receive milk daily. In 1981, for the action ¡Ay Sudamérica!, the group commissioned a squadron of six small planes to drop 400,000 flyers that were printed with an allusive manifesto about collapsing distinctions between art, life, and labor. It does not mention the censorious regime of Pinochet by name, but evokes instead the necessity of unconstrained thought, mental freedom, and the possibility of happiness, described as “the only great collective aspiration.” It includes the line: “We therefore say that the work of expanding the habitual levels of life is the only valid art form/the only exhibition/the only work of art that lives.” [2] Indeed, though the actions undertaken by CADA were diverse in genre, all of them prompted citizens to interrogate how the silencing of dissent can begin to seem routine, ordinary, and habitual. CADA restlessly pursued gestures that were meant to speak to the extreme conditions of depredation during the dictatorship – an “art that lives,” to cite the language of ¡Ay Sudamérica!, within the actual contested spaces of everyday life and material production.

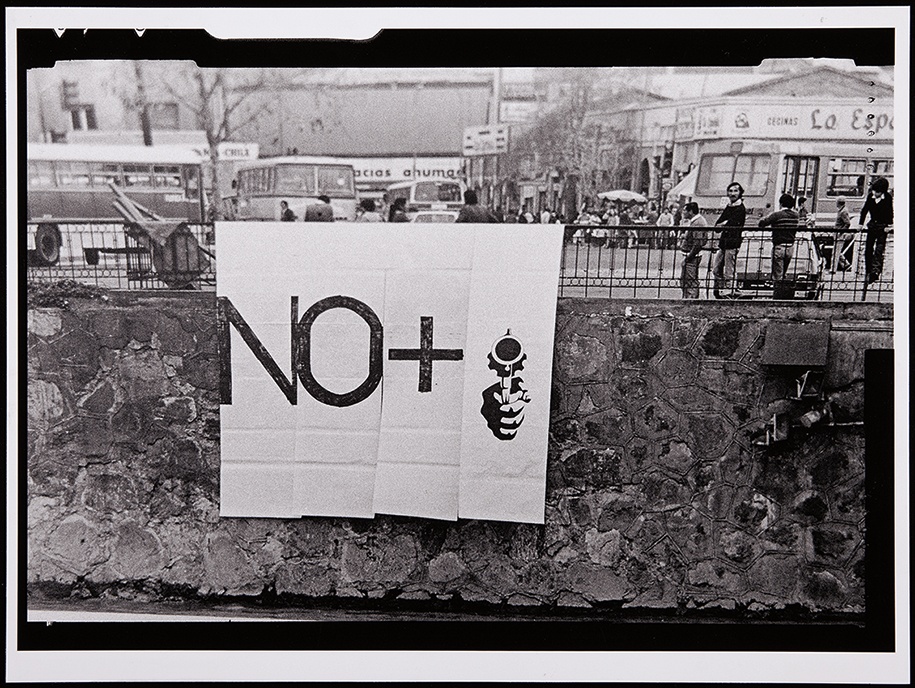

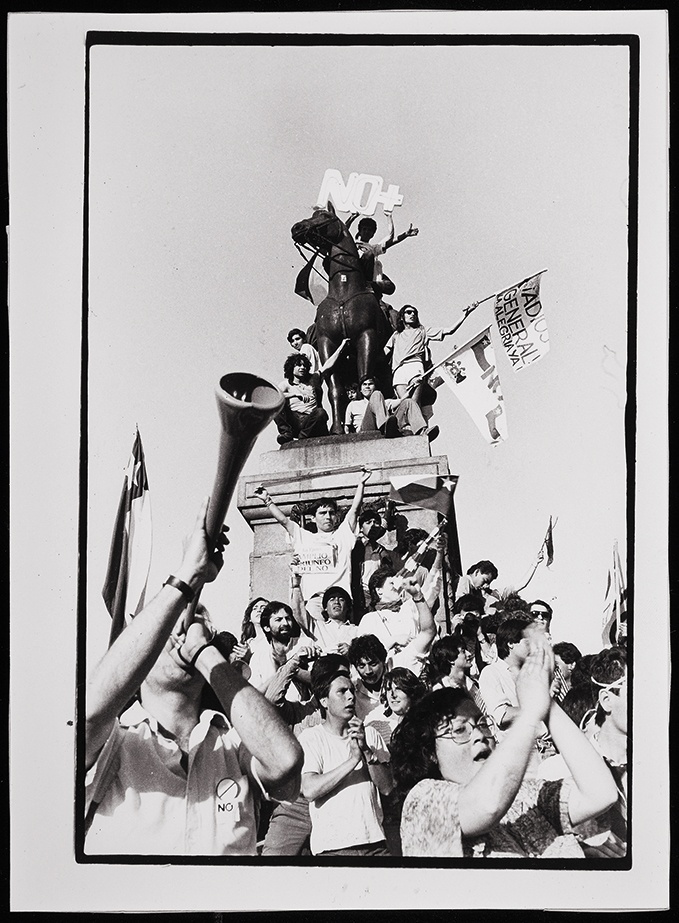

CADA (Colectivo de Acciones de Arte), „No+“, 1983–89

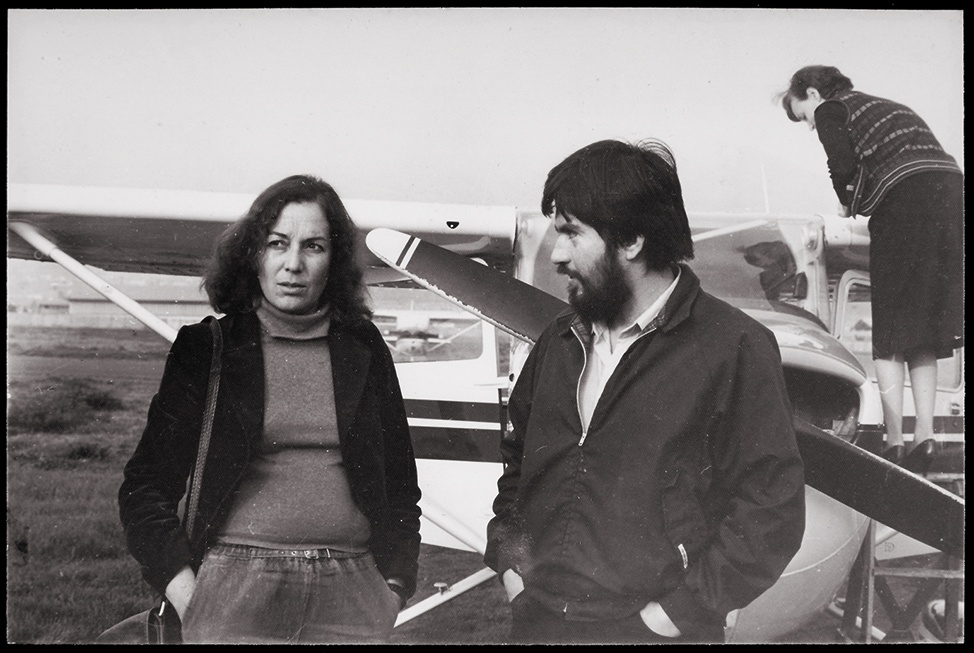

Those spaces included not only impoverished neighborhoods and urban territories but also factory floors: in the performance El fulgor de la huelga (The splendor of the strike), 1981, CADA’s members underwent a hunger strike inside a metalworks that had been declared bankrupt, leaving all its employees out of a job at a time of rising unemployment rates throughout Chile. Documentation of El fulgor includes short videos and photographs of the five members lying on the ground like corpses, swaddled in dark blankets emblazoned with “C.A.D.A.,” which has been neatly stenciled on with white paint. In front of them, a microphone is set up to record the muffled sounds of their movements. In a different video clip from El fulgor, the five sit with their knees drawn up to their chests, heads tucked down and faces not visible, still swaddled in their blankets, drawing attention to the legacy of the hunger strike (in which an individual body deprived of food echoes the larger body politic deprived of basic rights) as a dissident tactic. As with many of CADA’s initiatives, the staginess of this one-day performance, with its carefully arranged lighting and blanketed bodies lined up in a lumpy row against a white wall, demonstrates that while the collective was intent on redefining art, it did not eschew aesthetic effects. Instead, CADA mimics military theatrics (such as flying squadrons of planes and dropping leaflets onto populations) as a necessary counter-spectacle to refute some of the State’s fascist powers.

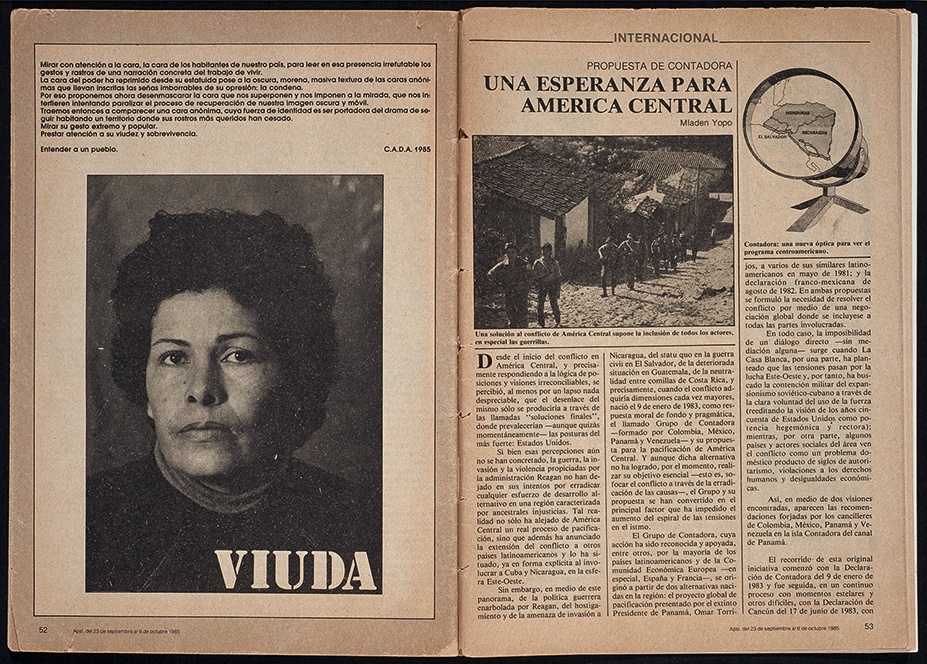

CADA (Colectivo de Acciones de Arte), „Viuda“, 1985

Importantly, two of CADA’s five members were women – Eltit and Rosenfeld – and both of them, separately and together, worked on projects beyond the purview of CADA that addressed feminist issues, including Eltit’s 1983 novel Lumpérica, a piece of experimental fiction that thematizes feminized physical pain and self-harm as an effect of economic marginalization and civic disenfranchisement. Issues of gender inflected CADA’s work as well, including the collective’s final official project, Viuda (Widow), from September 1985, a media intervention in which they inserted a photographic portrait of a woman whose husband had been killed during a national anti-dictatorship demonstration into the pages of four magazines and one newspaper that were critical of Pinochet. In the text that accompanies the tightly framed picture, CADA asks the reader to gaze upon the woman’s face as bearing traces of the many who disappeared under Pinochet, exhorting us to “pay attention to her widowhood and her survival.”

CADA (Colectivo de Acciones de Arte), „No+“, 1983–89

While many conceptual artists have used the pages of journals and newspapers as support and method of dissemination, CADA’s confrontational placement of the woman’s unsmiling visage within press outlets goes beyond an alternative system of display – it functions as a reminder of the reshaping of family structures during the dictatorship and the perseverance of wives, mothers, and daughters as they stood at the forefront of the resistance. Even after CADA disbanded, Eltit and Rosenfeld continued to work collaboratively, including on a documentary about a woman who sorts trash, and on their cocreated Crónica del sufragio femenino en Chile (Chronicle of female suffrage in Chile), 1994, an archival look at struggles for women’s rights written by Eltit and designed by Rosenfeld. [3] Their many projects together emphasize the importance of collective-making for feminist-socialist praxis, not least the rejection of sole, individual authorship, a kind of territorial ownership of ideas that many feminists understand as structured by and functioning in concert with capitalist property.

CADA (Colectivo de Acciones de Arte), „¡Ay Sudamérica!“, 1981

CADA’s most high-profile project was the participatory slogan No+, also called No más (No more). This rallying cry of negation and refusal was left open-ended for viewers and took many forms after it was first launched in 1983 as painted inscriptions in public space. It spread and multiplied, growing from the small group’s anonymous, deceptively simple declaration against the violence of the dictatorship to being one of the most pervasive and influential political slogans of the Pinochet era. An insurgent prompt that many other Chileans seized upon and completed (no + fear, no + tortures, no + disappearance), it appeared at pro-democracy marches on banners, scrawled on walls, and printed on placards. Repudiation was only the starting point for the provocation that was CADA’s No+, because its incompleteness acted as an implicit invitation for others to fill in, an act of incorporation in which the spectator/audience becomes a vital collaborator.

By nature unrestricted and unresolved, No+ has proved to be both enduring and flexible; it became the heart of the organized and forceful “campaign of no” that galvanized voters to oust Pinochet in the 1988 plebiscite. It circulated anew in October 2019, when thousands of leftist students in Chile poured into the streets to demand an end to ongoing suffering and precarity caused by Pinochet-era policies, but it also recently cropped up as a signature feature of far-right propaganda in Colombia. [4] This regressive appropriation of CADA’s initially progressive action demonstrates how “art that lives” can also mutate, taking on unexpected ideological registers or even becoming other to its origins as it proliferates.

Notes

| [1] | Archival materials related to CADA can be found at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía and Red Conceptualismos del Sur. |

| [2] | All translations by the author. The flyer with the original text can be viewed on the website of the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía. |

| [3] | For more on the feminist friendship of Eltit and Rosenfeld, see Natalia Brizuela and Julia Bryan-Wilson, “Speaking of Lotty Rosenfeld: ‘Gestures Dangerous, Simple, and Popular,’” October 176 (Spring 2021): 111–37. |

| [4] | For a brief sketch of the Colombian far-right usage of No+, see Ava Gómez Dava, “Colombia: El No + del uribismo,” April 4, 2016, on the celag.org website. |