The art of ceasing communication. The withdrawal from art, whether temporary or definitive, that women artists such as Lee Lozano, Agnes Martin, Cady Noland, Adrian Piper and Charlotte Posenenske have made, has been widely discussed and is now part of institutional historiography. Yet as the art historian Charlotte Matter shows in the following, the historicization of such practices of resistance merits critical scrutiny, in no small part because it reproduces mechanisms of inclusion and exclusion: How many other artists have stopped making art, their histories unwritten, because their withdrawals were so resolute that they left no traces to be rediscovered and marketed after the fact, or because they had never gained access to the art world in the first place? Matter makes the case for an evaluation of art’s suitability as a political tool.

Man’s strength lies in identifying with culture, ours in refuting it. – Rivolta Femminile, Manifesto

“Where do you stand with your art, colleague?” a man asks, muscular legs in a wide stance, his crotch almost at the center of the large-format painting. He has one hand on the knob of the door he has just opened while the other gestures out toward the street. There, a demonstration of the Communist Party of Germany marches by, rallying the working class to the struggle against wage theft, ever-mounting pressure at work, inflation, and political repression. His question is addressed to another man, who is sitting in the studio’s interior and has just put the first brushstroke of beige paint on a white canvas.

Bristling with masculinity, the canvas, painted by Jörg Immendorff in the early 1970s, is incapable of envisioning the worker as anything other than a man. The total absence of women colleagues is characteristic of the sexism that was widespread in left-wing circles at the time and denounced by the filmmaker Helke Sander in a September 1968 speech on occasion of the conference of delegates of the Socialist German Student Union – the word “student,” like the one for “colleague” in the painting’s title, is gendered in the masculine form. Sander accused the delegates of ignoring the specific oppression and systemic exploitation of women. By refusing to grasp that the personal was political, they were turning a blind eye to women’s concerns and effectively perpetuating patriarchal power structures. Sander touted the antiauthoritarian kindergartens run by parents’ initiatives as an alternative model. Her speech made history in no small part because Sanders’s invitation to the delegates to engage in dialogue went unheeded, prompting her colleague Sigrid Rüger, who was in the late stages of pregnancy, to rise from the audience and pelt the podium with tomatoes.

Politicized by the current events of that time, many cultural workers of the 1960s and 1970s tested various forms of resistance, with different degrees of stridency and radicalism (which is not to say that the two are strictly correlated). While Herbert Marcuse was loudly championing the “Great Refusal” and Alain Jouffroy, the “Abolition of Art” and an “art strike” – without proceeding to action themselves – feminist groups and movements were forming in numerous countries, taking concrete measures to advance the fight against systemic discrimination. Some pushed for legal equality and advocated reforms within the system, while others strenuously rejected such efforts and argued in favor of the revolutionary abolition of all existing structures. The Italian art critic and philosopher Carla Lonzi, for example, thought that “equality between the sexes is merely the mask with which woman’s inferiority is disguised [today].” This belief led her to ask, in an essay titled Sputiamo su Hegel (Let’s Spit on Hegel): “But do we, after thousands of years, really wish for inclusion, on these terms, in a world planned by others?” She did not have to answer the question. For Lonzi, it was clear that creating a wholly different society was now necessary, one whose values would not be predetermined by patriarchal ideologies.

Reform or revolution – that had long been the crucial question. Sheila Rowbotham’s history of feminist uprisings traced the open “conflict […] between the two feminisms, one seeking acceptance from the bourgeois world, the other seeking another world altogether,” back to the 19th century. In the introduction to her feminist anthology From the Center: Feminist Essays on Women’s Art, Lucy Lippard, too, acknowledged the dissensus. Taking critical stock of her own work, she noted that she still had deep roots in the art world that she had been protesting since the late 1960s: “I would like to revolutionize, but I am stuck with reform because of the context I work in.” As Lippard saw it, radical feminism’s ambition to change the world from the ground up was incompatible with an art system that, she believed, was amenable at most to gradual reform. In this situation, feminism became her motivation (and, as she herself conceded, her excuse) for staying in the field: “There are so few of us writing primarily on women’s art, and so few feminists in the establishment, that I feel needed. I am needed.”

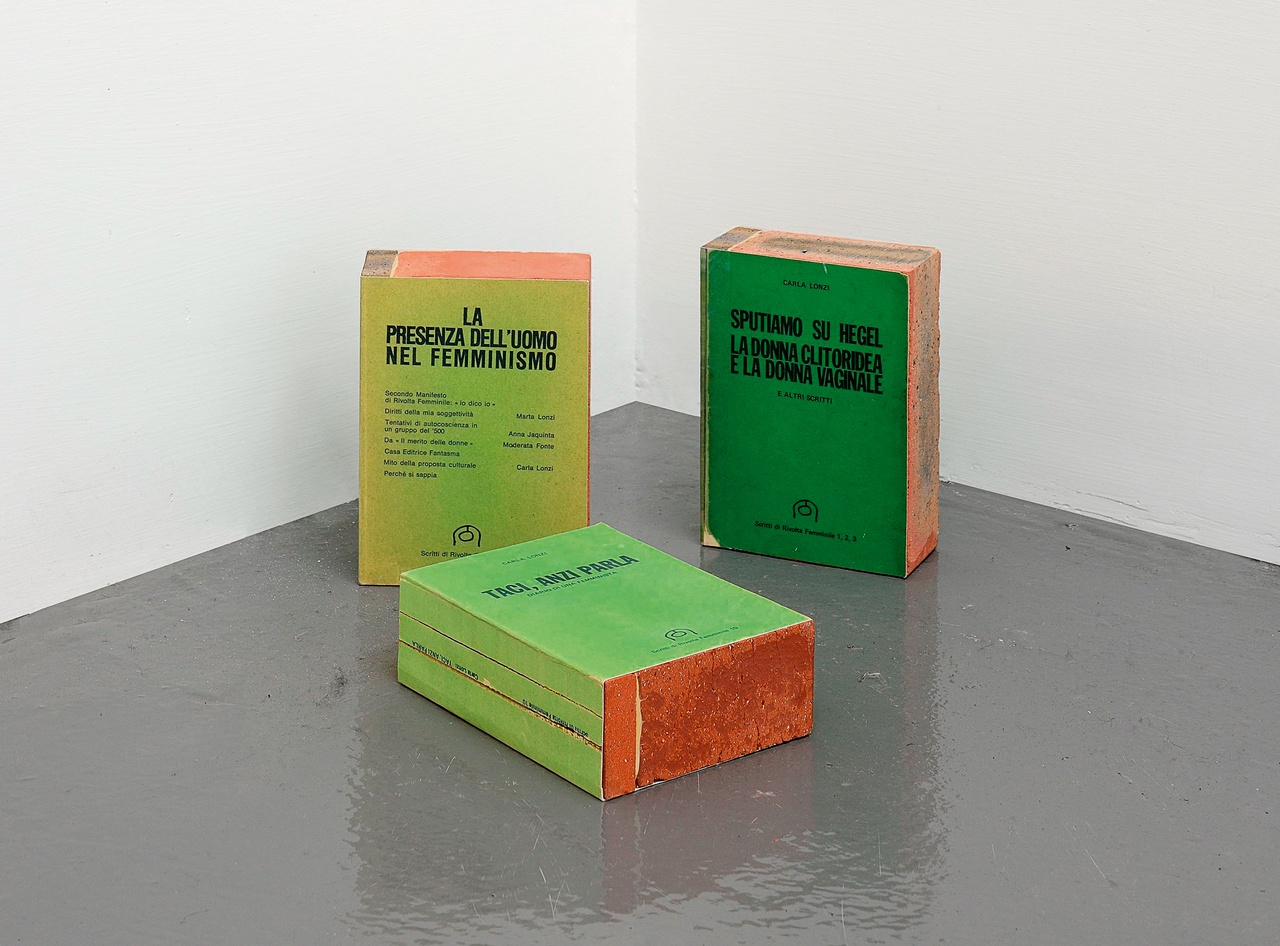

Lonzi came to a different conclusion. In 1970, she cowrote the manifesto of Rivolta Femminile together with the artist Carla Accardi and the journalist Elvira Banotti, which called on women to cast off once and for all the oppressive institutions of family, religion, and politics. That same year, Lonzi published a final sweeping condemnation of art criticism, pillorying the “great stupidity of the critic” (she chose the masculine form of the noun, possibly not by coincidence) and the “total disconnect” between him and the artist – and withdrew from the art world. Art criticism, she argued, sought to produce a form of knowledge that served to establish relations of power. She had already called into question the principle of authorial control over interpretation in earlier writings such as the long-forgotten book Autoritratto (Self-portrait), which was published in 1969. Composed of transcriptions of recorded and rearranged conversations with 14 artists, the polyphonic work challenged the conventions of art criticism by trading ostensible objectivity for radical subjectivity. In an effort to deconstruct established hierarchies, Lonzi intermingled her own voice with the artists’ words. Ultimately, however, she came to see her work as an art critic as incompatible with her feminist activism. A second Rivolta Femminile manifesto, released in 1971, rejected the “celebrations of male creativity” and proclaimed the authors’ refusal to take any further part in them. Striving for equality in the existing art system, they wrote, meant submitting to rules and values that had historically been defined by the patriarchy and alienated all others; only by repudiating it could women break free from dominant models and chart their own approach to art.

The members of Rivolta Femminile disagreed over how (and even whether) art and feminism could be reconciled. Unlike Lonzi, who left the art world behind, Accardi continued making art and, in 1976, became one of the eleven cofounders of the Cooperativa Beato Angelico, which proposed to present and document the works of women artists from the past and present. The eclectic programming in the short-lived exhibition space, located on a small side street in central Rome, ranged from 17th-century painters such as Artemisia Gentileschi to forgotten exponents of 20th-century avant-gardes such as Regina and the cooperative’s own members, including Accardi and Suzanne Santoro. According to Maria Bremer, the nonlinear quality of their exhibitions, which followed no chronological sequence, was a programmatic strategy designed to dismantle the continuity of a history dominated and written by men. Be that as it may, Accardi saw no contradiction in being actively involved in both art and feminism. When she was asked about her current pursuits in the 1970s, she replied that she was trying to intertwine her political and artistic interests.

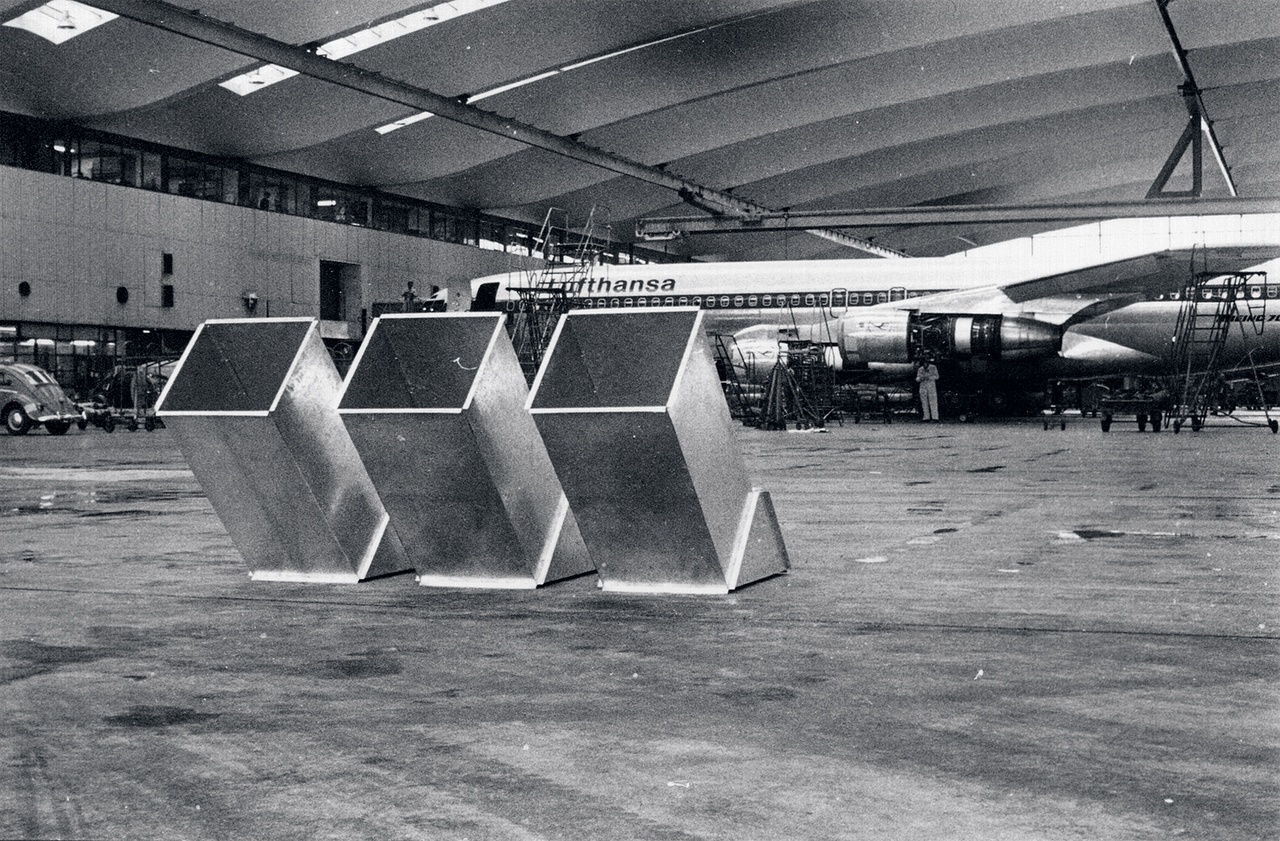

However, not all artists of the time were able – or willing – to bridge that gap. A well-known example is Charlotte Posenenske, who observed in 1968, “I find it difficult to come to terms with the fact that art cannot contribute anything to the solution of pressing social problems.” She stopped making art that same year and enrolled at the University of Frankfurt to study sociology. Her withdrawal is now a piece of art-world lore; art’s institutions have long brought her back into the fold and now smack their lips over extant works or posthumous reproductions prepared for consumption in lavishly designed publications and exhibitions. Lee Lozano’s, Agnes Martin’s, and Cady Noland’s temporary-to-definitive withdrawals have similarly been widely discussed and institutionalized. As for Lonzi, the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea in Rome acquired her archive a few years ago; over 16,000 documents (including notes, letters, postcards, private photographs, and reproductions of works of art) are now available in digital form on Google Arts & Culture. What would Lonzi make of the fact that her legacy has been reannexed to art and, more importantly, that large parts of it are managed by Google, a company in whose algorithms sexism and racism are structurally encoded? On the other hand, we ought to resist the temptations of romanticization and glorification and put these mythical withdrawals in perspective: many of them, it turns out, were contradictory upon closer examination. Agnes Martin, for example, maintained an ongoing correspondence from her desert refuge with her colleagues in the New York art world. Lonzi, too, continued to think about art after her withdrawal – even if only to frame a critique of its entanglement in patriarchal structures.

Finally, it is critical that we question the historicization of such practices of resistance because this process reproduces mechanisms of inclusion and exclusion. How many more have left the field whose histories remain unwritten because their withdrawals were so resolute that they left no traces to be rediscovered and marketed after the fact? Or because they had never gained access to the art world in the first place? Like art history as a whole, the history of withdrawals from art is littered with blind spots. Virtually no one, for example, talks about the artists who dropped out after laboring under precarious conditions and outside the Western art market. Take Argentina, where, under the ever more onerous censorship regime and repression of General Juan Carlos Onganía’s military dictatorship, numerous artists abandoned painting in the 1960s. The phenomenon was so widespread that a newsmagazine, in 1969, even put an image of a funeral wreath hung over an easel on its cover beneath the words “Argentina: The Death of Painting.” Yet these withdrawals make for less compelling stories, simply because not much is known about many of them and because their trajectories are often less than straightforward. They do not lend themselves to reduction to pleasingly cut-and-dried tales: some of the artists in question, for example, branched out into commercial lines of work, a decision that is at odds with conventional ideas about politically committed art.

One of these artists was Margarita Paksa, who stopped showing her work in institutional exhibitions in 1968 after various run-ins with censors; she organized a series of events on the political situation in Latin America (which were suspended after police warning) and gave drawing lessons in the informal settlements of Buenos Aires. She also founded a company that manufactured plastic furniture – much to the displeasure of some of her erstwhile companions. The artist Lea Lublin, for one, took a highly critical view of Paksa’s switch from art to commerce, remarking in a letter, “Margarita Paksa is struggling with her own contradictions, doesn’t want to create works of art for bourgeois consumption yet produces plexiglass furniture…” The critic Jean Clay, who had met Paksa during a visit to Argentina, presumably disapproved of her change of course as well. Clay was preaching a renunciation of the system of objects at the time, summoning a “wild” or “savage art” that would resist domestication by the art market and commercial interests. Like so many others, however, he failed to recognize the privileged position that undergirded his advocacy of such a stance. His lack of awareness of economic realities blinded him to the circumstances of many artists who needed to make a living. Paksa herself, in retrospect, offered a pragmatic explanation of what led her to go into business, noting that her future as an artist looked precarious once she had withdrawn from all exhibitions. Longstanding misconceptions about political art even today cloud the understanding of committed practices that are quieter and more complex than vociferous calls for a grand refusal. Paksa’s example is a cautionary reminder that the withdrawal from art is also a question of privilege.

Likewise absent from the popular narratives about such withdrawals are the countless names of those who were compelled to stop before they had even really begun: all those, for example, who could not afford to study art because they had no family to rely on for support and could not forgo a regular income; all those who were excluded from the outset or utterly disillusioned by structural racism and sexism in art schools, exhibiting institutions, and the art market; all those with impairments and chronic illnesses for whom the neoliberal art world had no ramp, no sign language interpretation, no outlet to power a thermal blanket, and certainly no patience. Anyone who was not a white, heterosexual, affluent cis man without disabilities living in a Western metropolis had no assurances that they would ever gain the kind of attention from the art world required for a withdrawal from art that would be noticed as such. For Arthur Rimbaud, Ludwig Wittgenstein, and Marcel Duchamp, to give three prominent examples, their renunciations of poetry, philosophy, and art, respectively, far from negating their previous work, retrospectively conferred a distinctive authority on them, an air of “unchallengeable seriousness,” as Susan Sontag aptly noted in The Aesthetics of Silence. Their withdrawals ultimately aimed to demonstrate their superiority, implying, in Sontag’s words, that “the artist has had the wit to ask more questions than other people, and that he possesses stronger nerves and higher standards of excellence.” It was a decision they could only make because they had already exerted a certain authority. Yet how effective is a strike when no one notices that you have not shown up for work?

Adrian Piper, like Posenenske and around the same time, wrestled with the fecklessness of art as a political tool. A series of events in the spring of 1970 – specifically, the US invasion of Cambodia, the women’s movement, the fatal Kent State and Jackson State shootings, and the closure of the City College of New York, where Piper was studying philosophy – prompted her, too, to retreat from art, a decision she explained in the following statement she sent as her contribution to the exhibition “Conceptual Art and Conceptual Aspects”:

The work originally intended for this space has been withdrawn. […] I submit its absence as evidence of the inability of art expression to have meaningful existence under conditions other than those of peace, equality, truth, trust and freedom.

In her autobiographical essay “Talking to Myself” (1970–73), Piper later remembered that she needed time off to ponder her “position as an artist, a woman, and a black.” Yet she also arrived at the pragmatic conclusion that she “hardly had enough power as an artist to effect any significant change by withdrawing from shows […] [or] signing petitions.”

One important lesson we can draw from Piper’s temporary withdrawal is the need to consider strategies of resistance from an intersectional perspective. Gestures of protest, while guided by an emancipatory idea, only too often fail to disentangle themselves from racist, sexist, and ableist mechanisms. That is how, in 1970, Robert Morris and other artists, declaring an Art Strike against racism, sexism, oppression, and war, withdrew from the Venice Biennale and proposed to organize a counter-event. As originally planned, however, their so-called “Liberated Biennale” was to feature only artists who had received official invitations to Venice – exclusively white men – and so would ultimately have bolstered their dominance at the expense of those whom their protest was ostensibly meant to benefit. As Faith Ringgold would later recall, the Art Strike’s unstated true purpose was “to give superstar white male artists a platform for their protests against the war in Cambodia.” At the urging of Ringgold, Michele Wallace, and other members of the hastily convened Women Students and Artists for Black Art Liberation, the “Liberated Biennale” underwent a genuine liberation and in the end was open to all would-be participants. Still, Wallace’s observation about the Western cultural avant-garde rings bitterly true even today: its protest against racism and sexism and recognition of the reality of white male hegemony, yet its demonstrable impotence to break with them.

Many of the questions that sparked fierce debate and controversy in the 1960s and 1970s have lost none of their urgency. As the institutions of art find themselves under mounting pressure from global protest movements and museums confront ever more vocal calls for their decolonization, artists and creative workers, especially if they are politically aware, face the question: Where do I stand with my art? Which compromises am I ready to make in order to get my message across? How can I reconcile work that is critical of the system with a commercial funding model? Does my art serve to legitimize business dealings that are based on exploitative conditions and (re)produce social inequality?

Should I not drop out?

In March 2020, an open letter by Paul Maheke under the title “The Year I Stopped Making Art. Why the Art World Should Assist Artists Beyond Representation; in Solidarity” prompted a broad discussion. Skipping between points in time, places, and identities, Maheke’s first-person narrator lays out the manifold reasons why someone might be forced to withdraw from art. His intimate narrative perspective, fluctuating between bodies and contexts, proves an effective device, the poignant medium of an embodied solidarity. The art system’s inequities, Maheke’s letter reminds us, predate the global pandemic – still, the date of its publication draws our attention to the way a situation that was already precarious then has since deteriorated sharply.

“I don’t feel like making any art just now,” Jesse Darling similarly muses on the voice-over track of a poetic video essay they composed during the second wave of Covid-19 infections. Instead, the time had come to pause, to think, to listen to others instead of speak. Yet as they hastened to add, this interruption should not be mistaken for a general work stoppage. In addition to an elaborate mail-art project that circumvented conventional institutional channels of art distribution and instantiated an economy of immediate gift-giving, Darling performed work in a wide variety of ways, including caring for others and for themselves. But even today – almost 50 years after the international Wages for Housework campaign and despite the inflationary use of the term “care” in exhibitions and anthologies – activities that are thought of as reproductive are typically invisible because they are still not perceived or recognized as work.

Acknowledging vulnerability, getting involved in the community, caring for others, and thus the question “Where do you stand with your art, colleague?” have taken on new urgency since the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic. There is nothing new about the atrocious police violence driven by racism and transphobia, or the neoliberal healthcare industry accepting with a shrug that some vulnerable individuals will not make it. But the moment seems to have arrived when a critical mass realizes that the personal has always been political and that this is more than just a feminist slogan. In this situation, many cultural workers increasingly state personal-political reasons for withdrawing, taking a time-out, or refusing to participate. More specifically, they decline, for instance, to continue providing certain forms of emotional labor without pay, or they stand up against the pressure to perform exerted by a disconcertingly professionalized art world, demanding sympathy when their energies are limited. Instead of launching another art strike or “downing their tools” – a gesture that sometimes comes with more than a dash of machismo – artists may at long last be ready to rethink the concept of work itself.

Translation: Gerrit Jackson

Charlotte Matter is an art historian. She teaches at the University Zurich and coordinates the master’s degree program Art History in a Global Context.

Image credits: 1. Courtesy of Claire Fontaine and T293, Rome, photo: Roberto Apa; 2. © Basis-Film Verleih, courtesy of Deutsche Kinemathek; 3. Courtesy of the Estate of Charlotte Posenenske and Galerie Mehdi Chouakri, Berlin; 4. © Marie Orensanz, courtesy of Alejandra von Hartz Gallery; 5. © and courtesy of Generali Foundation Collection, permanent loan to the Museum der Moderne Salzburg; 6. Jesse Darling

Notes