Who is mourned, and how do individuals who are considered unworthy of being mourned assert their worthiness? At least since the murders committed by the National Socialist Underground in the early 2000s and, more recently, the racist murders in Hanau – where, on February 19, 2020, a 43-year-old shot ten people and then killed himself – society’s denial of some people’s losses and grief emerged as a key concern for anti-racism initiatives in Germany. Parallel to this, affect-theoretical racism studies have sought to depathologize the traumatic experiences of racialized people and change the way grief is worked through, bringing it into view as a political articulation. In the following pages, the sociologist Çiğdem Inan reconstructs the long history of victim-blaming in connection with racist and right-wing violence in Germany and develops the theoretical notion of “dispossessed mourning.”

In a conversation on the racist murders in Hanau, Serpil Temiz Unvar – mother of Ferhat Unvar, one of the murder victims – responded in the negative when asked whether she had been able to grieve for her murdered son. “I’ve not been able to mourn, I won’t mourn. Not in any normal way, anyway. Obviously I’ll cry, I’ll be sad. Obviously I’ll break down sometimes, often, but I won’t let it on to anyone. I’m just going to keep fighting. That’s what Ferhat would have done.” She adds: “Because that’s what they’re used to. Us dying, us crying, then being forgotten. Not this time.”

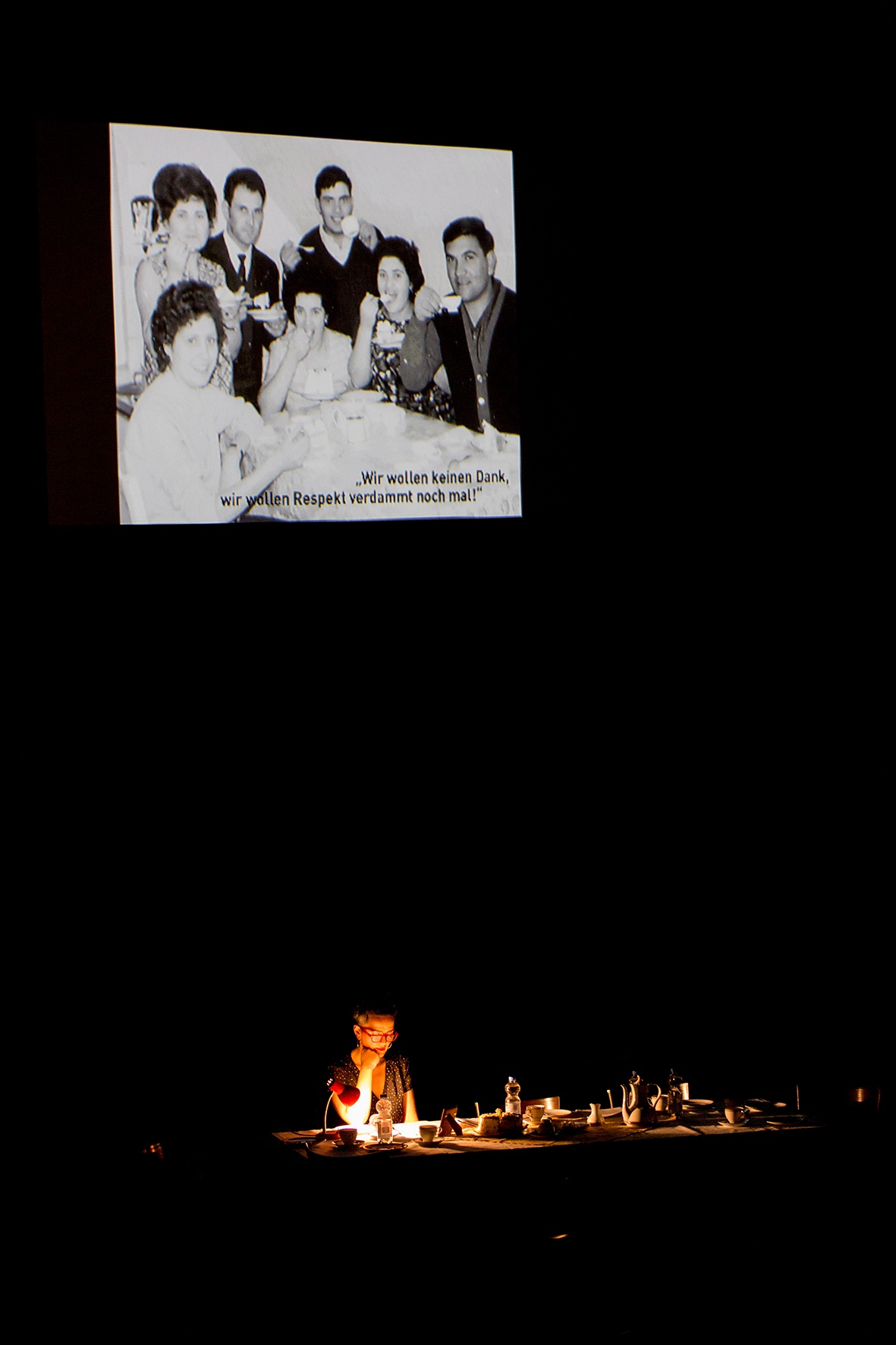

Taking denialism of racist violence as its starting point, this text is about the relationship between dispossessed mourning, negative affectivity, and fleeting resistance, and is dedicated to Serpil Temiz Unvar’s “not this time.” It gathers within it all the work, paradoxes, and difficulties of a politics of grief in the context of racist violence. With just three words, grief is articulated in its public withdrawal and annulment; it is shown in its non-showing, and thus in the knowledge that for this grief there will be no public reciprocation, condolence, or testimony. At the same time, these words inaugurate a politics that recognizes the denial of loss and pain as more than simply an element of (or, more precisely, the most immunitarian expression of) racist violence but, instead, as a politics that makes these experiences of dispossession into a resource for social change. This text begins with the words “not this time” in order to sketch a politics that is characterized by its operation at the site of loss, denial, and violence: a site from which the power of a different social relationality – one that defies and seeks to abolish divisions of grievable and non-grievable lives – can be legitimized. The figure of dispossessed grief thus stands front and center in the following reflections. When loss and grief are denied, subjects are confronted with the deprivation of their capacity to feel. In countering this, how can affect and grief be made starting points for political change without falling back into forms subject to the logics of appropriation and representation? To what extent does grief prove to be a contested arena of power, violence, and resistance?

Especially since the National Socialist Underground (NSU) murders, grassroots anti-racist organizations have focused on the deprivation of loss and grief. The issue of how the failure to perceive racist violence and the injuries it causes intercedes into grief and renders it impossible – thus triggering retraumatization – has become an explicit field of political practice and engagement. This activist development has intersected with a theoretical one: since the 1990s, negative affectivity and bad feelings have been a key focus in racism research based on affect theory. This encompasses the political power of racial melancholia and depression, of feeling brown and racialized fear, and the related importance of “metrics of grievability.” Negative affectivity is understood as an element of the “archives of feelings” in which racialized people’s experiences of trauma are stored. Based on the “palpability of structural racism,” theories of affect have de-pathologized negative affect, lending it visibility as a political articulation. Rather than being reduced to individual experience, the sociality of the feelings of loss, disenfranchisement, and grief that characterize vulnerable lives is emphasized. In Europe, anti-racist “grief activism” or a “transversal grief” have largely been framed in relation to the EU’s necropolitical border regime and the countless deaths in the Mediterranean. But as the work of grassroots anti-racist organizations demonstrates, these questions arise in Europe not only in the politics of migratory borderlines but also with regard to the structural racisms of social institutions with their manifold, fragmented borders, be it in the context of the police apparatus, of healthcare, or of deadly racist violence and the lack of political and legal will to recognize it and come to terms with it. This text uses the figure of dispossession to explore political grief from the perspectives of affect and resistance theory.

The activist slogan “racism kills” brings together these highly diverse practices of racist border demarcation, through which forms of existence deemed worthy of life and not worthy of life are distinguished from one another and differential degrees of dehumanization are introduced. In the 1950s, Frantz Fanon explained how these border demarcations create daily and structural “zone[s] of nonbeing,” in which human beings are exposed to violent conditions while, at the same time, positioned beyond any right of recognition. As hazards to life, practices of this kind are slow and hidden, but at times fast and immediate; they are linked to their own denial, which is to say, the derealization of the endangered form of life. These derealizations have become a significant point of departure for current efforts to remodel the political and the resistant. In recent years, grassroots anti-racist organizations have been clear that – in keeping with Fanon’s analysis – the indirectly and directly lethal violence of racist and right-wing attacks creates dehumanizing, derealizing economies that act on several social levels. These have concentrated into the symptoms of victim-blaming in police investigations and media reporting, whereby victims and survivors of racist attacks are subject to culturalizing suspicions and themselves criminalized as perpetrators, thus exposing them to material precarization. When police and legal investigations perform these kinds of victim-blaming reversals – denying racist motives, invoking the lone-wolf theory ever more frequently, covering up state involvement, blatantly ignoring victims’ experiences, refusing to provide economic compensation or official commemoration, thus ultimately making it impossible for survivors and the bereaved to grieve – the multigenerational traumas that still today mark the continuation of racist violence are further reinforced. This is how Heike Kleffner diagnoses the normalization of racism in Germany, as resulting from victims not only being forced “to work through the trauma of loss alone, but also having to compensate for the social stigmatization and isolation that results from investigations characterized by racist victim-blaming and institutional racism.” Taking as their starting points events such as the 2004 nail-bombing in Cologne’s Keupstraße, grassroots organizations like Keupstraße ist überall (Keupstraße is everywhere) and Dostluk Sineması describe how victim-blaming led to an atmosphere of social desolidarization, in which feelings of grief were overlaid with feelings of shame, fear, and insecurity as those impacted by the attack lost their businesses or were unable to work. This schema – of grief work being made impossible – has involved acts of “a structural lack of empathy.” This includes when the joint plaintiffs in the National Socialist Underground trial were relegated to roles as bystanders, denied the chance to openly speak about their experiences of racism or to criticize the official investigations, and, in 2022, when survivors and bereaved relatives of victims of the Hanau attacks were refused co-planning roles for the official remembrance ceremony, with many friends and relatives even being denied access to the cemetery. The denial of racist violence and, thus, its implicit legitimation are painful, retraumatizing experiences for victims of racist attacks. This making-impossible of grief occurred, for example, after the 1996 right-wing arson attack on a refugee center in Lübeck, a crime for which no one was ever charged and which was not even recognized as racist, despite the residents later issuing a joint statement defending themselves against being criminalized as suspects and also demanding a full and open investigation and secure residence permits. The grassroots Hafenstraße’96 organization seeks, like other such initiatives, to set in motion a “history of remembrance and indictment” against these processes of denial, in lockstep with a “history of losing loved ones, of harm, of fear, of traumatization, of afflictedness, of being unable to believe, and of contradiction.” In its Trauer, Wut und Widerstand (Mourning, rage, and resistance) brochure, Bündnis Tag der Solidarität – Kein Schlussstrich Dortmund (Union for a Day of Solidarity – No Line in the Sand), a group founded in “reaction to the passivity of state authorities,” gathers and summarizes a wide range of struggles for a politics of investigative explanation and memorialization. Several grassroots organizations contribute to this effort, their “self-empowerment” and “support” having been vital to preventing the memory of racist murders from “fading into obscurity.” They recall the deaths of Oury Jalloh and Amed Ahmad in police custody as paradigmatic examples of denied killings. Both men burned to death in fires in their prison cells in 2005 and 2018, respectively. The Hamburg-based Initiative zum Gedenken an Ramazan Avcı (Initiative in Memory of Ramazan Avcı) likewise demonstrates how annual memorial events have created a distinct forum for remembrance, pushing “the stories of victims of racist violence and the years of suffering and trauma into the present” and helping to shape “the culture of remembrance and memorialization in Germany.” The urgency of such a push is also reaffirmed in the context of the racist attacks on and murders of contract workers in former East Germany, which are among many incidents being saved from the “history of being-forgotten” by the Initiative 12 August group. The organization focuses on histories such as the intergenerational memory of the night in 1979 when over 200 Germans chased 30 Cuban contract workers through the streets, as revenge for their self-defense against racist harassment and violence. For Raúl Garcia Paret and Delfin Guerra, attempted escape ended in their deaths, which remain unsolved and have not been officially commemorated even today, blocked by Halle’s public prosecutor. Deprivations of this kind are variations on a decades-old tradition of racist violence. They serve to derealize the work of grieving, remembrance, and memorialization that has characterized migrant history in Germany and that Fatima El-Tayeb has termed “racist amnesia.”

Less than Grief: Dispossession and Resistant Modes of Affirmation

Inscribed into the anti-racist politics of grief is the antinomy of dispossession and its political meaning. On the one hand, grassroots organizations call for the grievability of migrant life in the face of deprived grief and the secondary victimization that follows from victim-blaming. On the other, they seek to transform the negative affects triggered by the dispossession of grief – fear, despair, and rage – into the strength to fight and the retrieval of autonomy and agency. Affective politics thus oscillate between the recognition of grief and its overcoming or “reworking” into agency, combined with a reclaiming of autonomous subjectivity. As vital as it is to exit from the making-impossible of grief and to ensure the audibility and visibility of experiences of racist violence, a series of dilemmas remain inscribed in this oscillation. On the one hand, continuities of racist violence compel the development of resistant practices that operate in zones of harm and traumatization; on the other, these practices involve a dangerous tendency to invoke a complete, self-owning subject as a political agent, thus erasing the fact – revealed in grief – that we are vulnerable and incomplete individuals by virtue of our relationality. The retrieval of what has been called “autonomous agency” could quietly invoke a subjectivity of proprietorship and sovereignty that takes us back to the problems of modern domination, whose apparently universal subject is particularized by (post)national communalizations. In view of this dilemma, it is vital to distinguish between two figures of dispossession: one mediated by the history of violence, the other existential and political. In the continuities of violence, the second figure is only accessible via the first; it demands the “refusal of what has been refused,” which is to say, refusal of the powerful fictionality of autonomous subjectivity itself, thus opening up space for the contagion, affectation, and receptivity that make transversal solidarizations and politicizations possible in the first place. At hand here is not a fatalistic resignation to anti-racist politics being forced to operate in contexts of violence but rather an affirmative demand to pay greater heed to the practices that “act” under logics of representation – subject, meaning, autonomy, and consummation – and in zones of organized violence and dispossession, without demanding appropriation and alienation.

Particularly in Left Hegelianism and for young Marx, concepts of deappropriation and appropriation described a subject that, in order to take possession of itself and its active being, returns to itself via externalization of its powers and capacities. To the Feuerbach-inspired Marx, humanity was to be regarded as an all-around transformative being, able to act freely toward and actualize the possibilities of all objects that affect it sensorily. As a sensory being of this kind, humanity is passive, receptive, and receiving – an all-around object of being-affected. For Marx, this ultra-passivity makes it possible for producers to appropriate the world, retrieving themselves through their transindividual activities and putting an end to the dispossession by religion, state, or economy, in which they were confronted with their own strengths as “powers completely alien to them.”

It is via an expanded concept of dispossession that contemporary theories of negative affectivity and political grief key into the critical gestures of Marxist theory, but they do so while breaking away from the idealizing inversion of dispossession and moving toward an all-around appropriation. On this score, there is significance to Judith Butler’s objection that understanding the ties that entangle us with others as merely relational is insufficient. We are not simply “constituted” by them; rather, they are something we are “dispossessed” by in our constitutions. Grief and separation are politically powerful because they manifest this experience of unpossessable relationships with others, revealing dispossession of self as an existential sensation. From this perspective, grievability is a precondition of life. When, on the basis of social norms and conditions of exploitation, racialized distinctions are established between grievable and non-grievable modes of existence, the result is a life that is dispossessed in terms of domination – a life that is considered socially non-belonging and that, being undead, does not appear in the space of social phenomena. It is neither affectable nor affecting. Racist immunization against the existence of Others and their deaths thus implies violent denialism of social relationality that is multidimensionally inscribed into capitalist modernity and constantly drilled via modes of subjectivization. Alluding to Foucault, Butler demonstrates how the racist phantasmagoria of undead life is negatively vivified within a biopolitical “metric of grievability” resulting from an image having been created of populations defined by “nullification or foreclosure of [their] living character.” These “disposable peoples” are prone to direct and indirect killings by state and institutional authorities, who consider them “on the cusp of death or already dead.” On framing the central problem of an anti-racist politics of grief, the question thus arises: What is the affective and perceptual schema on whose basis the destructiveness of racialized mechanisms of violence becomes socially unidentifiable, thus no longer “uncoverable” or “unmaskable,” because the killing of “a nonliving population” is in fact not a killing at all but rather, as Butler concludes, “just a certain clearing away of some curious obstruction from the path of the living”?

Again, Fanon is pioneering in his conception of the unintelligibility of racist violence. In seeking to explain this violence, he went beyond simply setting out psychoanalytic concepts to instead develop theories of affect, the body, and particularly the “historical-racial schema,” thus advancing the theorization of negative affect and the ontologization of racist dispossession. Fanon’s analysis of the dehumanizing and deanimating effects of racism as – in Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenological terms – the destruction of the “body schema,” the disrupted connection to the sensual world, as “hemorrhage” and fixing-in-place by the white gaze, forms the primal scene of a theory of racism in which it becomes possible to discuss the circulation of negative affects and the racist “affective ankylosis” toward the Other, the “numbing” of receptivity.” In keeping with Hegel, Fanon defines the “racial epidermal schema” and the non-being of Black existence as negative intersubjectivity characterized by refusal of recognition, fragmentation of the body, affective disquiet, and rigidification of visual reflexivity. For Alia Al-Saji, the impossibility of opening up a different future manifests a deadlocked “rigidity” of racializing affects that hinders any possibility to “become otherwise.”

The unintelligibility of the fear or pain felt by racialized Others has been traced by Kyla Schuller to notions of sensuality and drive in 18th- and 19th-century aesthetics and biology, which show how a “key vector of racialization” has been inscribed into our understanding of affect processes. The civilized body was equipped with the ability to mentally appropriate sensory stimuli via “emotional reflection”; the racialized body was, on the contrary, characterized as unaffectable in a qualified sense, as “unimpressible” in terms of aesthetic cultivability and historical time.

This silencing of the Other – noted from Fanon to Schuller to the present day – reflects the immunitarian structure of racist violence, which in its unintelligibility has become the starting point of the politics of grief. Theories of affect drawn from critiques of racism go beyond Fanon’s paradigm of recognition to analyze the affective legacies left by “racialized histories of genocide, slavery, colonization, and migration” and induce the “feeling historical” of those who have dropped away from the categories of proprietor-subjectivity and “good citizens” – the “melancholic migrants” and “affective aliens.” In distinguishing between experiences of dispossession and retreating from logics of appropriation or self-appropriation, it becomes possible for anti-racist politics to identify fleeting and hard-to-represent acts of grief work that surpass even the Freudian notion thereof. The positions articulated by David L. Eng and Shinhee Han are worthy of deliberation here: they affirm that Freud’s call to replace lost objects is nonsensical in the context of experiences of racism, since some objects (such as linguistic or social belonging) are unattainable due to racist exclusions, while others (up to and including life) are irretrievably destroyed by racisms. It is for this reason that melancholy is depathologized in theories of affect drawn from critiques of racism, with the protective introjection of lost objects being affirmed as “productive political potential.” At hand here is a political agency that frees itself from confronting object substitution with melancholically incorporated loss. This agency is less than grief work and more than a melancholic “crypt.” This can be explained by the fact that under conditions of continued structural racisms, anti-racist politics of grief are about stepping in at the site of racist violence, at the threshold of dispossession. To “excavate a wound” and affirm the rupture emerges here as a form of a paradoxical healing that uncovers a voice speaking from a position of non-belonging, from a position of being delocalized from the historical. This results in a political adherence to “loss and alienation” that, instead of seeking to reproduce suffering, looks to transform loss into disidentificatory relations of affect that persist in a transformed being-dispossessed, in transversal capacities of feeling and solidarities. In these political forms, the reaction to dispossession of grief is not one of an appropriating counter-identification. Avoiding the arrival of new group identifications, incompleteness, being-united, and affectability are welcomed as political empowerment, thus subverting the recognizability of victim groups, or what Butler calls “necropolitical targeting,” through which empathy and paternalism find their way into political actions.

Alongside anti-racist critiques of derealized grieving, there is an aim here to explore how political undercurrents or lines of flight emerge in zones of nonrecognition and derealization of life. This was guided by the question of how grieving can be experienced as an affect of resistance, without being taken into ownership and closed off as an identificatory and normative principle of healing. Engaging in this manner with dispossessed grieving opens up a view of long-term migrant struggles, within which an affective knowledge of the deprivation of loss of mourning is permitted. These resistances go beyond simply articulating political demands of remembrance to actually transforming them. Affectivity, sadness, and dispossession are accepted as signatures of politics; representative politics is opened up to the power of the unrepresentable. A politics of dispossessed grief thus becomes thinkable and feelable, in subversion of the classic conception of emancipation as a reclamation of autonomous subjectivity. Dispossessed grief focuses instead on practices that defy zones of violence and that are serious in their approaches to the social relations that manifest themselves in grief as an expression of the political. At the limits of intelligibility, or in the “zones of nonbeing,” nonidentical and resistant relations of affect step forth, transcending the violence of racist immunization and dehumanization from within. The transformation of social conditions is not relegated to an afterthought – post-liberation, post-emancipation, post-equality – and is instead situated in a micropolitical now of abolition practices and transversal solidarities. Serpil Temiz Unvar’s “not this time” can be understood as a call to decamp into a different experience of grief, to escape the vicissitudes of domination’s appropriation and dispossession of grief, making it possible to seek new paths that are less than grief work and more than melancholic closure.

Translation: Matthew James Scown

Çiğdem Inan is a sociologist who lives and works in Berlin. Her teaching and research focus on affect theory, poststructuralism, critical migration sociology, queer feminist theory, critical racism research, and postcolonial social theory. As a publisher, she is part of the b_books publishing collective, where she recently coedited a new edition of C. L. R. James’s The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution.

Image credits: 1. © Paula Markert; 2. © Ayşe Güleç, photo Axel Schneider; 3. Photo Jasper Kettner; 4. © spot_the_silence (Rixxa Wendland and Christian Obermüller), photo Axel Schneider; 5. © PRSPCTV Productions; 6. © Ma.ja.de. Filmproduktions GmbH

Notes