MELANCHOLIA AND MOURNING IN THE WORKING CLASS

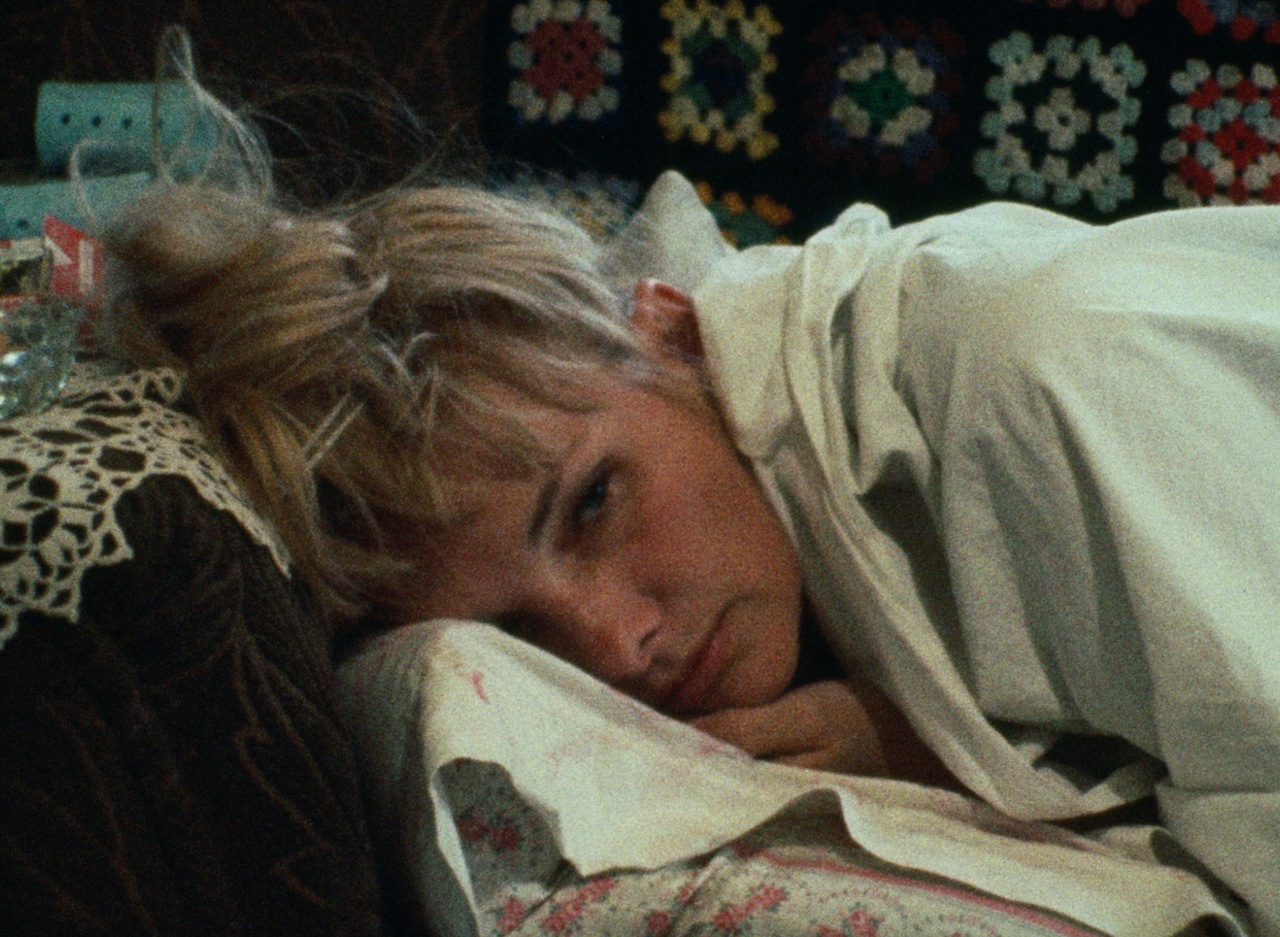

Barbara Loden, „Wanda“, 1970, Filmstill

We were scum, trash, refuse that didn’t fit into the system. – Monte from Claire Denis’s film High Life

In 2019 I began work on a text that would become The Melancholia of Class: A Manifesto for the Working Class. The impetus for the project was a seeming paradox. How was it possible, I wondered, for contemporary capitalist society to insist that there is no working class while this seemingly nonexistent subject, the working class, is vilified by the very society insisting they do not exist. [1] At the same time, I recognized melancholia as a symptom of the working-class subject. Melancholia, according to Freud, occurs when the melancholic experiences the loss of an object that remains unknown to the sufferer. As a result, they are unable to grieve the loss of the lost object. In the working-class subject, I recognized these symptoms and located this loss as the loss of their working-class subjecthood. In the book, I examined the lives of working-class writers, musicians, and filmmakers whose work is imbued with this affect. In the United States, for example, because the concept of social class has been removed from social discourse, there is an overall societal consensus that social class no longer exists and, as a result, there is no working class. We are all one class, the current belief system insists, and if one of us is unable to survive, this failure is the symptom of our own laziness. I had hoped, through the writing of the book, to perform a kind of speech act, one through which the working class might recognize themselves, the result of which would be a kind of mass class consciousness. In this essay, I hope to explore further the concept of melancholia and the working class and to examine how this state indicates a potential for emancipation.

The working-class subject is surrounded from the moment of their birth until their final breath by capitalist society, a society created by the bourgeois class. Through education, the various forms of media, the family, and so on, the beliefs and values of the bourgeois class are interpolated into the working-class subject and through habit become second nature. We are unaware, in other words, of the presence of capitalist ideology. Indeed, what we might call our most private, interior voice, the non-sound of our own thought, is actually this external voice, internalized. [2] Under the spell of capital, internalizing the voice of capital inside them, the working-class subject becomes unable to recognize their own voice subsumed beneath the voice of the internalized, magnetizing voice. Ideology, as Althusser writes, “is a ‘representation’ of the imaginary relationship of individuals to their real conditions of existence.” [3] It is a dream-state interpolated into the subject. This process of interpellation is all it takes to get subjects to, as Althusser writes, “go all by themselves.” This interpolation of false consciousness results in a working-class subject unaware of their working-class subjecthood, fully aligned with the ideology of the bourgeois class. The working-class subject, having internalized these beliefs that are not their own, lives in a dream-state, unaware that they are unaware. When the working-class subject “forgets” the existence of social class and thus their own working-class subjecthood, this truth is repressed in the unconscious. Because it is repressed, though it no longer exists in the conscious mind, it does not disappear. Instead, it returns to the surface in the form of dreams, symptoms, and parapraxis, or slips of the tongue.

In order to survive, the working-class subject must assimilate into capitalist society (they must work, for example, to sustain themselves and their family). There is a cut where the working-class subject abandons their working-class alliance, and it is at this juncture that the working-class subject becomes fully absorbed into capitalist society. For most, such a rupture never occurs, or rather, its occurrence is never known by the working-class subject. Because capitalist society insists there are no social classes and thus no working-class subject, many of the working class never know they are working class to begin with. Whether this cut is conscious or not, what has been lost – one’s working-class subjecthood – cannot be grieved because, according to society, it never existed in the first place. What I am describing here is symbolic death. The working class exists and yet the working-class subject has been removed from social discourse. Of course, this was not always the case. In the United States, for example, the cutting of social programs and the loosening of financial regulations during the 1970s, alongside the normalization of the concept of meritocracy, have resulted in an erasure of the concept of social class and, hence, the concept of the working class. In Germany too, as Michael Heinrich notes, the term is avoided and replaced by ambiguous terms that serve to obfuscate the issue of class entirely. [4] Erased from social discourse, the working-class subject has been relegated outside language, which is to say the working-class subject has been relegated to the Real, that which cannot be articulated through language, that which remains unfathomable, beyond comprehension.

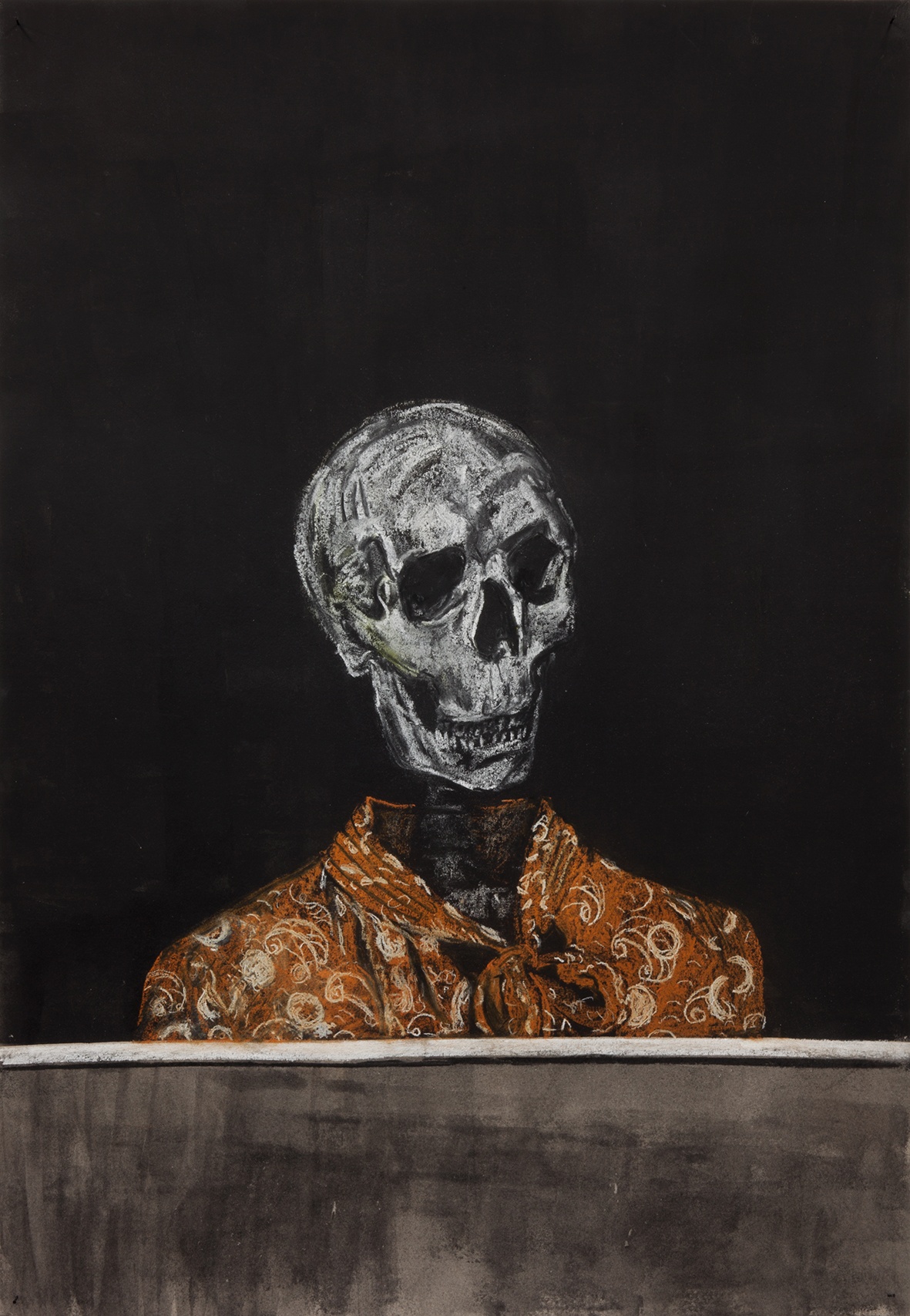

Ariane Müller, „Other Places (silk dress)“, 2019

I began my project by examining the Freudian melancholia I’d diagnosed as a symptom of the contemporary working-class subject. Freud, in his seminal essay “Mourning and Melancholia,” compares the two concepts. “Mourning,” he writes, “is regularly the reaction to the loss of a loved person, or to the loss of some abstraction which has taken the place of one, such as one’s country, liberty, an ideal, and so on.” [5] Melancholia takes the place of mourning for some, and is described by Freud as follows:

The distinguishing mental features of melancholia are a profoundly painful dejection, cessation of interest in the outside world, loss of the capacity to love, inhibition of all activity, and a lowering of the self-regarding feelings to a degree that finds utterance in self-reproaches and self-revilings, and culminates in a delusional expectation of punishment. This picture becomes a little more intelligible when we consider that, with one exception, the same traits are met with in mourning. The disturbance of self-regard is absent in mourning; but otherwise the features are the same. [6]

In mourning, the sufferer necessarily faces the reality that what or whom they have loved is gone, and they must now place their energy entirely upon this lost object. This is the work of mourning: turning away from one’s day-to-day life and engaging in the necessary labor of working through this loss. Such work entails attending to each memory and expectation connected to the lost loved object. This, in turn, necessitates the slow detachment of these memories and expectations from the sufferer’s libido. Such work takes time and an enormous amount of energy. But once this has been accomplished, the work of mourning will indeed be complete: the symptoms bound to the subject’s mourning will abate, and they can return fully to their lives. The mourner is able to work through their grieving because they are aware of what has been lost. With melancholia, on the other hand, what or who has been lost remains unclear, as Freud explains:

In yet other cases one feels justified in maintaining the belief that a loss of this kind has occurred, but one cannot see clearly what it is that has been lost, and it is all the more reasonable to suppose that the patient cannot consciously perceive what he has lost either. This, indeed, might be so even if the patient is aware of the loss which has given rise to his melancholia, but only in the sense that he knows whom he has lost but not what he has lost in him. This would suggest that melancholia is in some way related to an object-loss which is withdrawn from consciousness, in contradistinction to mourning, in which there is nothing about the loss that is unconscious. [7]

Freud writes that with both melancholia and mourning, the same symptoms appear, aside from one: the reduction of the sense of self, which occurs only with melancholia. As the Lacanian psychoanalyst Darian Leader writes, “In mourning, we grieve the dead; in melancholia, we die with them.” [8] The darkness implicit in both is worked through and thrown out when the mourner has completed the grieving process. But for the melancholic, this darkness does not abate. Rather, it contaminates the subject’s interior, as Freud writes:

In mourning it is the world which has become poor and empty; in melancholia it is the ego itself. The patient represents his ego to us as worthless, incapable of any achievement and morally despicable; he reproaches himself, vilifies himself and expects to be cast out and punished. He abases himself before everyone and commiserates with his own relatives for being connected with anyone so unworthy. […] This picture of a delusion of (mainly moral) inferiority is completed by sleeplessness and refusal to take nourishment, and – what is psychologically very remarkable – by an overcoming of the instinct which compels every living thing to cling to life. [9]

It is the ego with which the subject has an antagonistic relationship. Indeed, what has occurred is that the subject’s hatred for the lost object has been transferred onto the subject’s ego. In melancholia there is a surplus, lacking in mourning, which Freud describes as an “ambivalence” with regard to the lost love object:

In mourning, too, the efforts to detach the libido are made in this same system; but in it nothing hinders these processes from proceeding along the normal path […]. This path is blocked for the work of melancholia, owing perhaps to a number of causes or a combination of them. Constitutional ambivalence belongs by its nature to the repressed; traumatic experiences in connection with the object may have activated other repressed material. Thus everything to do with these struggles due to ambivalence remains withdrawn from consciousness, until the outcome characteristic of melancholia has set in. [10]

Gustave Courbet, „Les Cribleuses de blé / The Wheat Sifters“, 1854

In relation to the working-class subject, the ambivalence Freud attributes to melancholia can be understood as an ambivalence toward their own social class. Having internalized this ambivalence toward the working class, the working-class subject is confronted with a paradox of affect. What they have lost remains unknown, and yet this unknown loss renders them stuck: melancholic. Through interpolation of this ambivalence toward their own class, they have, through the practice of habit, come to hate the very thing they remain unaware of having lost.

The melancholic finds themselves further stuck within a stuckness, stuck between two worlds: the past (where the lost object exists) and the present (where they are unable to access the lost love object). Within this liminal, dead space, the melancholic exists in a zombie-state. Describing her life before making her film Wanda, Barbara Loden said, “I was like the living dead. I lived like a zombie for a long time.” Having internalized capitalist ideology, the working-class subject is further propelled into the false belief that if they just work harder (work more hours, hold more jobs, save more money, and so on), they, too, can become a capitalist.

The melancholic working-class subject, unaware of their social class, remains unaware of the object they have lost. Indeed, they remain unaware that they have lost an object to begin with. This state of unknowing, or forgetfulness, is the consequence of repression and of what Hegel calls habit, the practice of repetition that begins as a deliberate choice, the result of which is an aspect that becomes sublimated into one’s everyday being. After something becomes habit – learning to ride a bike, for instance – this new behavior or practice becomes second nature. What at first seems strange and may initially be experienced as a shock to the system – a task that necessitates a number of incongruent movements, each movement requiring mental focus – eventually becomes, in a sense, nothing at all: entirely natural, unnoticeable. In Philosophy of Mind, Hegel posits habit as a means to treat madness, which is to say, as a means to free the subject from their fixation on one particular representation:

This being-together-with-one’s-own-self we call habit. In habit, the soul is no longer captivated by a merely subjective particular representation and evicted by it from the centre of its concrete actuality; it has so completely received into its ideality the immediate and individualized content presented to it, has made itself so at home in the content, that it moves about in it with freedom. [11]

Though habit allows the subject freedom, due to its numbing quality, habit may also result in a subject’s becoming unaware of their habituated actions. As Žižek explains, “the status of habit changes from organic inner rule to something mechanic, the opposite of human freedom: freedom cannot ever become habit(ual), if it becomes a habit, it is no longer true freedom.” [12] Through habit, one acts without thinking about one’s actions or about why one is engaged in these actions in the first place. In habit, we no longer know what we are doing. It is as if the action is doing us. And this mechanical behavior – fine when we are driving a car or riding a bike – becomes something entirely different, something indeed sinister, perilously close to death; as Hegel writes, “therefore although, on the one hand, by habit a man becomes free, yet, on the other hand, habit makes him its slave.” [13] In relation to the working-class subject, habit may result in a forgetting of the reality of capitalism. When, for example, the working-class subject works every day at a job that ruins their mind and body in order to survive, this very act, through habit, becomes nothing at all. Oppression becomes habit, it becomes second nature. What we have, then, is a working-class subject who does not know they are working class and, because they do not know they are working class, cannot grieve the loss of this subjecthood.

In his catalogue of various forms of madness in Philosophy of Mind, Hegel includes melancholia (Melancholie), which he describes as “the mind’s constant brooding over its unhappy representation, never rising to the vitality of thought and action.” [14] The contradiction in which the melancholic finds themselves, at once stuck on the lost object while, simultaneously, trapped inside the dream-state, is precisely how Hegel defines what he calls Verrücktheit, or derangement. By allowing themselves to become stuck with one particular representation, the subject is driven out of their intellectual consciousness, back into their previous state of abstraction. When the subject falls back into their abstraction, they sink back into what Hegel calls the Night of the World: “The human being is this Night, this empty nothing which contains everything in its simplicity – a wealth of infinitely many representations, images, none of which occur to it directly, and none of which are not present. This [is] the Night, the interior of [human] nature, existing here – pure Self.” [15] At the same time, Hegel writes, the subject finds themselves “in the contradiction between its totality systematized in its consciousness, and the particular determinacy in that consciousness, which is not pliable and integrated into an overarching order.” [16] The “in” here, in this sentence, is critical, because it suggests that the subject is within the contradiction, not merely in opposition to it. Furthermore, the melancholic working-class subject, having lost their working-class subjecthood, is stuck between the past and the present.

In The Melancholia of Class, many of the subjects I examined engaged in acts of negative freedom such as drinking or using drugs to excess or withdrawing from society. The concept of negative freedom originates with German idealism and, in its simplest iteration, is the ability to say no to everything outside of one’s self and to withdraw back into the self. Of negative freedom, Hegel writes: “The human being can abstract from every content, make himself free of it, whatever is in my representation I can let it go, I can make myself entirely empty … The human being has the self-consciousness of being able to take up any content, or of letting it go, he can let go of all bonds of friendship, love, whatever they may be.” [17] Though such acts of negative freedom are often self-destructive, even at times resulting in death, they can provide a temporary escape from capitalist reality. And though such acts may appear passive, as irrational acts of self-destruction, such acts can also be understood as attempts at resistance. In addition, such acts are often unconscious. When, for instance, Anita G., the main character in Alexander Kluge’s film Abschied von Gestern, steals a coworker’s cardigan, she insists the act was instinctual. “Es war alles ganz gefühlsmäßig,” she tells the judge – “It was all very instinctive.” By engaging in an act of negative freedom, the working-class subject destroys all possibility of rehabilitation, thus determining their fate. The mere act alone, then, provides a means by which to mark the outer limits of what they are willing to tolerate. When the working-class subject engages in an act of negative freedom, they drop back into their interior; they fall back into madness. Thus, the working-class subject is confronted with a paradox: either drop back into their interior dream-state (madness) or assimilate into the dream-state of capitalism (madness).

Alexander Kluge, „Abschied von gestern / Yesterday Girl“, 1966, Filmstill

Furthermore, the working-class subject exists both inside and outside society, is an “element for which there is no proper place in the structure,” as Žižek writes. [18] And, indeed, the working-class subject is nothing: they have nothing but the power of their own labor (as opposed to the capitalist who has rent, profit, or wages). Pushed to the margins, symbolically dead, the working-class subject is, at the same time, integral to capitalism, is, indeed, its symptom. When the working-class subject, who is nothing, turns away from bourgeois society (and thus “tunes away” [19] so as to no longer hear capitalist ideology), recognizing their working-class subjecthood, it is then that this “nothing” has the potential to become an insuperable stuckness, a stuckness with the potential to jam up the incessant flow of capitalism’s dream-state. When organized, the working-class subject is nothing but its (proletariat) class. And yet, it is the working-class subject, the proletariat, who holds the potential for emancipation. Without organization, without the nothingness of other working-class subjects, this potential remains mere potential: only with others can the full possibility of this nothingness be realized. By vanishing into the nothingness (the anonymity of their shared social class), the working-class subject has the potential to rupture capitalism’s dream-state. As Terry Eagleton writes:

In becoming nothing but the scum and refuse of the polis – the “shit of the earth,” as St Paul racily describes the followers of Jesus, or the “total loss of humanity” which Marx portrays as the proletariat – […] Only those who count as nothing in the eyes of the current power-system are sufficiently askew to it to inaugurate a radically new dispensation. [20]

Excluded from bourgeois society, reduced to a form of “nothingness,” the working-class subject has the potential for emancipation through the actualization of this “nothingness.” Coming to class consciousness and therefore locating their lost object, the working-class subject moves out of the state of melancholia. The working-class subject exists now in an inverse of melancholia: where before they were stuck on the particularity of their lost object, they are now stuck on the particularity of class struggle.

According to Hegel, when we encounter great upheaval or change, we experience a moment of instability within which we are no longer who we were and yet we are not yet altered. In that moment, we are without a nature. In a sense, then, in this discrete moment, we are nothing. Hegel cites the French Revolution as one example of such an external upheaval. Such an interruption in the perception of the temporal, resulting in a feeling of instability, “deranges” the subject’s world, what Hegel describes as “eine Verrückung der individuellen Welt eines Menschen.” Here, the word Verrückung suggests both a madness and displacement of one’s individual world. The working-class subject, stuck in the particular determinacy of emancipation while also stuck in flow, is thus deranged and displaced. This combination of madness and displacement indicates a force with a potential to intervene with the incessant flow of capitalism. At the same time, the working-class subject is a series of stucknesses. To that end, when the working-class subject turns away from bourgeois society, returning to their intrinsic nothingness, and hence acting as if its rules no longer apply (positioning the political over the economic), the working-class subject holds the potential to jam up, and thus rupture and destroy, capitalism.

Cynthia Cruz is a PhD student at the European Graduate School, where her dissertation work focuses on Hegel’s concept of Verrücktheit and the possibility of emancipation. The author of The Melancholia of Class: A Manifesto for the Working Class and Disquieting: Essays on Silence, she is currently at work on a book exploring negative freedom and the working class.

Image credits: 1. © Janus Film; 2. Courtesy of the artist and Schiefe Zähne, Berlin; 3. Musée des Beaux-Arts, Nantes, public domain; 4. © Kairos Film

Notes

| [1] | When I refer to the working class, I am referring to Marx’s definition of the working class and specifically his definition from The Communist Manifesto: “In proportion as the bourgeoisie, i.e., capital, is developed, in the same proportion is the proletariat, the modern working class, developed – a class of labourers, who live only so long as they find work, and who find work only so long as their labour increases capital. These labourers, who must sell themselves piecemeal, are a commodity, like every other article of commerce, and are consequently exposed to all the vicissitudes of competition, to all the fluctuations of the market.” Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, “Manifesto of the Communist Party,” in Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels Collected Works, vol. 6, 1845–1848 (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1975), 490. |

| [2] | Louis Althusser, On the Reproduction of Capitalism: Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses, trans. G. M. Goshgarian (London: Verso, 2014), 157. |

| [3] | Ibid., 181. |

| [4] | Michael Heinrich, An Introduction to the Three Volumes of Karl Marx’s Capital, trans. Alexander Locascio (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2012), 14. |

| [5] | Sigmund Freud, “Mourning and Melancholia,” in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, vol. 14, 1914–1916, trans. James Strachey, (London: Hogarth, 1957), 243. |

| [6] | Ibid., 244. |

| [7] | Ibid., 245. |

| [8] | Darian Leader, The New Black: Mourning, Melancholia, and Depression (Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2008), 8. |

| [9] | Freud, “Mourning and Melancholia,” 246. |

| [10] | Ibid., 257. |

| [11] | Hegel, Philosophy of Mind, trans. W. Wallace and A. V. Miller (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2007), 134. |

| [12] | Slavoj Žižek, “Discipline Between the Two Freedoms,” in Mythology, Madness and Laughter: Subjectivity in German Idealism, ed. Markus Gabriel and Slavoj Žizek (London: Continuum, 2009), 99. |

| [13] | Hegel, Philosophy of Mind, 134. |

| [14] | Ibid., 125. |

| [15] | Hegel, Hegel and the Human Spirit: A Translation of the Jena Lectures on the Philosophy of Spirit (1805–6), trans. and ed. Leo Rauch (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1983), 19. |

| [16] | Hegel, Philosophy of Mind, 115. |

| [17] | Hegel, Vorlesungen über Rechtsphilosophie, ed. K.-H. Ilting (Stuttgart: Frommann Verlag, 1974), 4:111–12. |

| [18] | Slavoj Žižek, Disparities (London: Bloomsbury, 2016), 27. |

| [19] | Alain Badiou, Can Politics Be Thought?, trans. Bruno Bosteels (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018), 93. |

| [20] | Terry Eagleton, Trouble with Strangers: A Study of Ethics (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008), 186. |