WEATHERING: SLOW ARTS OF TRANS ENDURANCE

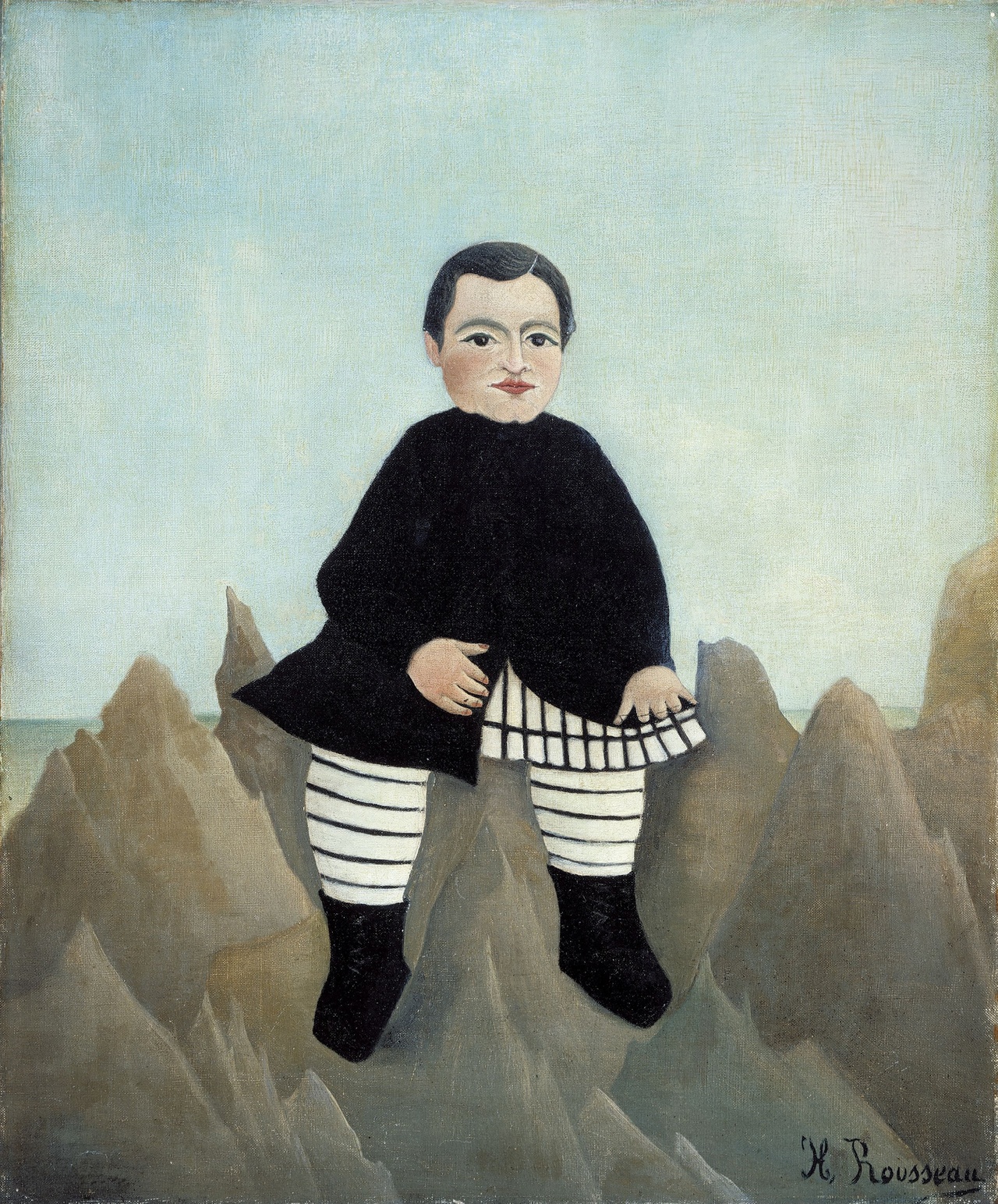

Henri Rousseau, „L'Enfant aux rochers“, 1895-97

It’s the onset of winter 2022; the light-gray sky settling in and the ground soggy with melt from the first snows. I’m waking up early and sitting in front of a sunlamp, determined that this year I’ll finally be able to stave off the descent of the strange assemblage that some of us call seasonal affective disorder. With the blue-white light blasting the glum from my body (that’s how it works, right?), I read “Rock Jenny,” a short story in Callum Angus’s A Natural History of Transition from 2021 about a kid named Jenny who decides to be a boy, then has second thoughts and becomes a girl, then outgrows that and becomes a rock, then a mountain, then decides to leave Earth and enter orbit as a moon. When she becomes a rock, her mother – a professor of geology – is very keen to know what kind of rock she has become, as that will reveal the sort of pressure she was under. It turns out she’s sedimentary – “layering over time until she became a mix of something else,” her mom says. “Just like she wanted.” The day comes when Jenny informs her family that she’s planning to leave the planet. They’re worried about the ways her departure and absence – the literal crater she will leave behind, “the size of several Olympic swimming pools” – will upset the stability of their everyday. [1] But leave she does, insisting on the validity of the decision to change, and then change again.

The message relayed here is that the only constant is change, that every sense of stasis or sameness is only temporary, that living itself is a ceaseless transition experienced at scales sometimes more perceptible and sometimes less. “Rock Jenny” affirms this and, in doing so, rejects the conventional expectation that transition happens, or at least should happen, once and only once. It affirms indecision and revision, choosing and then deciding to choose again, differently. These decisions don’t happen in a vacuum – they impact and are impacted by the lives of others, and these impacts leave perceptible craters – but they aren’t ambushed by interrogation. Jenny’s intimates respect her opacity; they don’t saddle her with the demand of confession; they don’t weaponize a will to know; and they don’t presume that she herself has such answers in advance of the existential experiment she’s about to embark upon. Such respect is a practice of care, a way of doing justice to the simultaneity of deep interwovenness and profound otherness that shapes any intimacy.

Angus gives us an account of transition attentive to questions of pressure and environment – the impinging and intra-active forces that co-construct Jenny. From her mother’s intent discernment of the forms of pressure that have made her the way she is to the increasingly frequent (thanks to anthropogenic climate change) rains that had “stripped her down to bedrock where erosion was slower but more painful, deepening the scars in her topsoil, exposing fossilized memories of mammals and more peculiar hurts she’d long unthought,” readers are gifted a vivid depiction of the entwinement of the corporeal and the atmospheric. [2]

Puppies Puppies (Jade Kuriki Olivo), „Inflatable Earth“, 2011

While thinking through the imbrication of environment and transition in Angus’s work, I found myself turning to Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s posthumously published essay “The Weather in Proust.” That day, a friend texted to ask what I was writing on; I wrote back “survival (and some other stuff).” The next day I saw her. She said she laughed when she read the text, because that’s what I’m always writing about. What else is there? Extinction, I suppose. The different scales at which death occurs, from being to species, from individual to kind.

Anyway. I was reading Sedgwick. The essay is ostensibly about Marcel Proust, whom I have never read. Like many, I suspect, I have meant to in a rather half-hearted way for years (then there is the other camp, those who have started, endured for a while, then halted – promising to return and finish one day). I mention this to say that I’d arrived there, at the opening pages of “The Weather in Proust,” mostly for what Sedgwick has to say about the weather, which exceeds the scope of Proust’s work. Another small admission: as a child, I would routinely zone out while watching the Weather Channel, which was a habit I had picked up from long days being babysat by my grandfather, who entered a daily fugue state in front of “Local on the 8s,” with its alternating soundtrack of smooth jazz and classical guitar. This attachment was a way of distancing from a domestic environment that was tumultuous often, violent sometimes. The Weather Channel held me. It was comfortingly routine in its programming and dedicated to forecasting the future, possessing a kind of clairvoyance that I found deeply reassuring. One could know what the next day would hold, or at least make a reasonable prediction concerning it.

When Sedgwick writes about the weather, she considers its “privileged place in discussions of complexity,” its status as a topic that dramatizes the relations between open and closed systems, a topos where “the absolutely rulebound cyclical economy” of “advanced human computational powers” and “the irreducibly unpredictable contingency of the actual weather” have come to be “conceptualize[d] together.” [3] Talking about the weather is another way of talking about “holding environments,” a term Sedgwick pulls from psychoanalyst and pediatrician Donald Woods Winnicott and summarizes as the providence of a protecting and nurturing environment that makes it “possible for the infant to think about something else, something beyond the mother’s care” (p. 11). A holding environment is an environment wherein one’s basic needs – “to breathe, to eat and drink, to have one’s weight supported” (p. 11) – are satiated. While the holding environment for Winnicott (and Sedgwick) is grounded in the infant-maternal relation, so-called healthy development necessitates the sustaining of such a holding environment as one’s social sphere widens. The concept echoes one of the key demands of movements for reproductive justice: the right to parent children in safe and healthy environments.

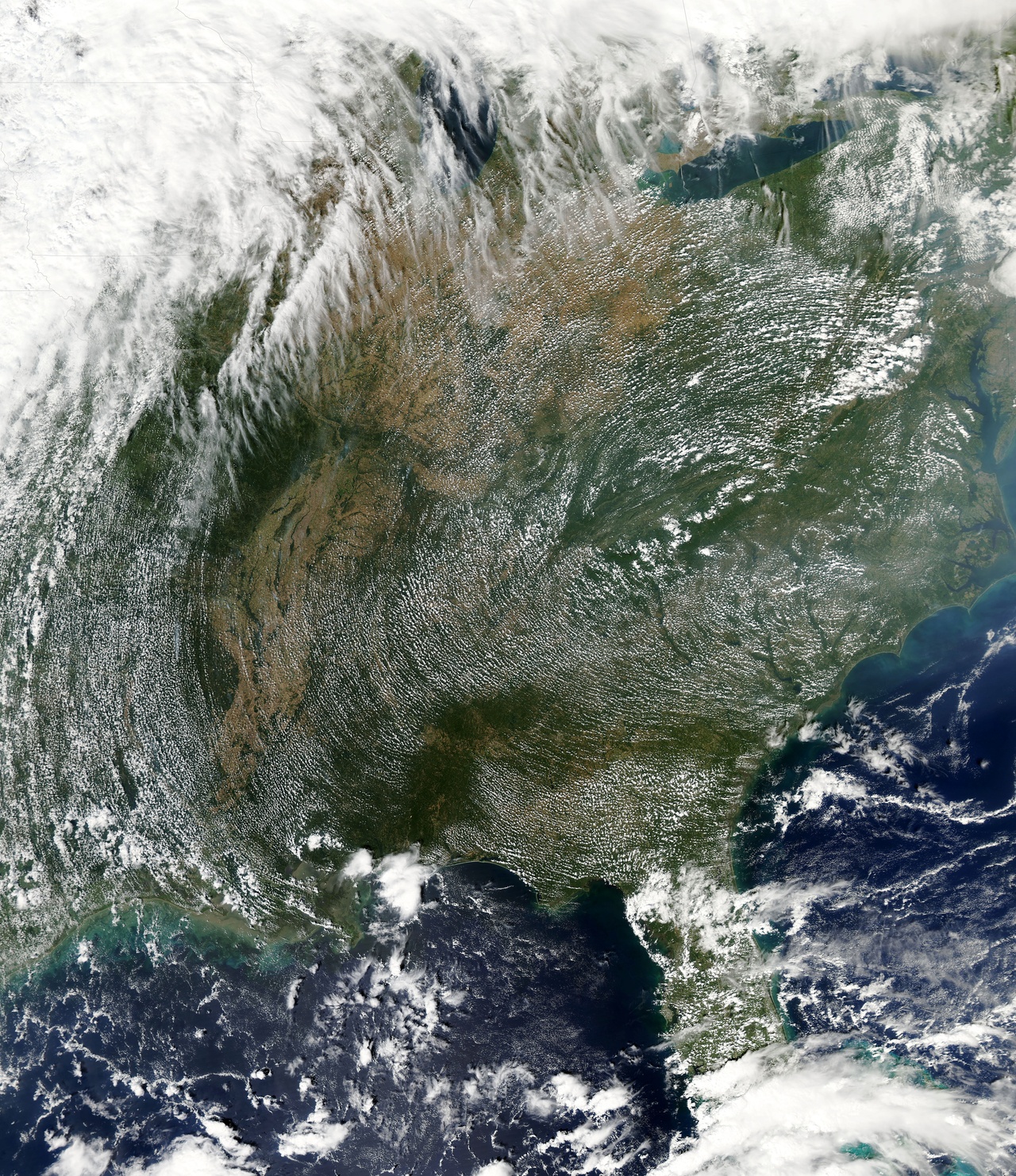

High pressure clouds / Hochdruckwolken, September 2010, satellite image / Satellitenbild

Of course, not all environments hold; not all weather systems are decent. One of the key fascinations of Proust’s work, for Sedgwick, is when his narrator describes himself as an “animated barometer” (p. 8) or as containing a “little barometric mannikin” within (p. 9). Sedgwick calls this barometric mannikin a “buoyant internal homunculus” that responds to atmospheric pressure, which, “compared to the much more obvious alternatives – temperature, wind, precipitation, even humidity … is a subtle, invisible, and indivisibly systemic index of weather” that means “nothing at all outside of a dynamic interpretive context” (p. 9). “Invisible for all its pervasiveness,” she writes, “atmospheric pressure – like the air itself – is easy for most people most of the time to take for granted.” In this way, it is like the holding environment – notable primarily when it is compromised or precarious; otherwise, it is “surprisingly pervasive, surprisingly easy to lose sight of, like the weather” (p. 15).

This internal barometer offers a way of thinking through the porosity of the subject, the “relation between an internal object and an ambient surround” (p. 32). It also works as a model for a kind of invagination – a shape shifting by way of enfolding that disrupts the fiction of a stable, fixed differentiation between the internal and the external, between the subject and what’s both within and beyond it. Sedgwick writes that “the beings in the universe are filled, in turn, like human barometers, with the stuff of the universe. This is as true for art as it is for the irreducibly complex systems and substances that constitute the weather” (p. 32). She remains curiously positive about this relation, making the internal barometer the figure that marks the openness of the subject to the new, the rupturing of closed systems, the delight of surprise, the engagement with the mystic, and the beautiful density of the rich inner life (with Proust’s work operating as an exemplar of all of these). Another way to put this: for her, in this essay, the environment always holds. The holding environment is what enables engagement with art, metaphysics, spirituality – all that lies beyond survival, the “something else” that a holding environment enables one to think. As Steven Swarbrick notes, Sedgwick’s text “sublimates bad weather.” [4] Shifts in the weather signal a revivifying arrival of the new, the unexpected, the surprising, the refreshing; an openness to being immersed in such shifts indicates a willingness of the self to be transformed.

I’m drawn to Sedgwick’s likening of one’s awareness of the complexity of a surrounding milieu to an internal barometer of sorts, one that tracks the subtleties of and shifts in atmospheric pressure. It feels like an astute way of thinking about what might otherwise be called affective attunement and its corresponding degrees, from detachment to hyperawareness. Sedgwick seems drawn to characters that have exquisitely sensitive internal barometers. I’d wager that for her, Proust himself is one of these – indeed, she writes that “everything in Proust depends on the ratio or relation between an internal object and an ambient surround. Inequality between them, or a collapse of either of them, leads to a collapse of the whole ecology of value and vitality” (p. 32). I suspect where our orientations (perhaps preoccupations is a better word) differ subsists in our own habits of attunement. Much of the trans art and literature that I’m drawn to, that I routinely think with, that I find resonant, if not exactly a source of repair and conciliation, is rendered in the collapse of whole ecologies. They don’t lament or seek to restore disequilibrium; they are rooted in it, committed to exploring what it means to subsist and persist in and through such collapse: what it means to weather. They want to understand the kinds of pressures we are under, since it is impossible to understand the forms we take, the forms we have taken, otherwise.

Nicki Green, „A Discrete History of Intimacy and Violence (double urinal basin with faucets)“, 2019

I turned back to Sedgwick’s thinking about weather after reading Eric A. Stanley’s Atmospheres of Violence. Stanley’s work, unlike Sedgwick’s, is grounded in a practice of thinking from always racialized trans and queer experiences of near life and slow death – that is, experiences of structural abjection, assignment to zones of nonexistence, violent obliteration, and intense marginalization. They use trans/queer not as an identity marker but instead to mark “the moment when race, nonnormative sexuality/genders, and force materialize at the impasse of subjectivity.” [5] Their archive – the lives and brutal, unjust deaths through which they chart an emergent theory of radical ungovernability – is, as artist, activist, and writer Tourmaline attests on the book’s back cover, “devastating.” Accompanied by this archive, Stanley renders hostile situations with careful, nearly forensic detail to build an account of trans/queer survival within suffocating surrounds. Another name for these surrounds is atmosphere.

Atmospheres suffuse, infuse, seep, absorb, infiltrate, creep, inundate, saturate, encompass. Because of the porosity of flesh and world, they get into you, you get into them. They are everywhere and no-place, tangible but not isolatable. They can be benign, miasmic, or curative, which is why Stanley modulates the term with the word “violence” when talking about trans/queer lives. There is no total escape from a violent atmosphere, though there are zones of reprieve, spaces that operate as what C. Riley Snorton, following Harriet Jacobs and Saidiya Hartman, terms “loopholes of retreat”: interstitial spaces of freedom within captivity; temporary environments of holding within broader nested systems of domination. [6]

There is a scene in Torrey Peters’s book Detransition, Baby that I come back to often, in part because I find it heartbreaking, in part because I find it hilarious. Toward the end of the novel, Reese – one of the central characters, a trans woman who is working through the complexities of planning to co-parent with her ex, Ames, who has detransitioned and is with a cis woman named Katrina, who is pregnant via sex with Ames – details her interest in Wim Hof, a “weird-ass Dutchman, known as the Iceman, who developed a method to withstand extreme pain” that has come to be known as “the Wim Hof method – a combination of breathing exercises and cold endurance trials, beginning with cold showers and moving to immersion in frozen lakes – intended to help adherents withstand pain and even control autonomic bodily systems.” [7] She was introduced to the method by a date who had started exploring it to deal with his erectile dysfunction by freezing himself “beyond performance anxiety.” Turns out that it works, or at least seems to. Reese reports that though “his skin was so cold that she felt as though she were embracing a corpse … the guy fucked like a god.” Afterward, they watch a short Vice documentary about Wim Hof (“a typical Vice piece: a credulous white guy doing things he ought not to, filmed in neutered gonzo style”), and Reese becomes intrigued after learning that Hof had lost his wife to suicide. She “let[s] herself become captivated” by him.

Years later, grieving, she finds herself on the shores of the summertime queer hub Riis Beach in May, on the very first warm day of the season. The water is still frigid. Remembering how Wim Hof’s cold immersion enabled him to find a “place beside pain but not in pain,” she wades out until she’s completely submerged. The beach is crowded, though, and she’s promptly rescued by a Speedo-clad muscle queen who is wasted enough to not feel the cold. The assumption is attempted suicide; she tries to explain that it’s not, repeating “Wim Hof method” over and over.

But the boundary is unclear; the pursuit of a place beside pain but not in pain risks the no-place of death. Watching the (real) documentary that the (fictional) date recommends to Reese, it becomes clear that the difference between death and healing is a matter of incremental and intensifying exposure, coupled with breathing and cognitive strategies that enable one to psychosomatically endure longer and longer immersions. Over time, the body acquires higher levels of brown adipose tissue, which enables one to maintain a higher core temperature even while submersed in freezing water. The body finds the form it needs to endure; it transforms in response to the kind of pressure it is under. Reese is obsessed with Wim Hof because he has taught himself to endure what would otherwise annihilate. When the question is survival, how one weathers the weather is the paramount concern. Sedgwick suggests that access to an adequate holding environment is key; Hof teaches how it is one might hold oneself. That Reese is lured by such a lesson doesn’t surprise me. That such a lesson amounts to microdosing exposure to hostile environments doesn’t surprise me either.

Jes Fan, „Systems II“, 2018

Jes Fan’s work, specifically Systems II and Systems III (both 2018), also teaches lessons about holding. Known for rendering objects of (perhaps grotesque, always sublime) beauty with politically charged biological materials (estrogen, testosterone, melanin, urine, semen, blood), in these pieces he constructs apparatuses that function as elaborate scaffolds, those ubiquitous support structures that make renovation possible. Upon these scaffolds rest glass globules, with some spaces seemingly purpose-built for supporting the specific shape of a particular form. Within the globules, testosterone, estrogen, and melanin are suspended in silicone, held within the once fluid, then plastic, and now fragilely static glass. He says, in multiple interviews, that he works with glass because he’s interested in process, flux, becoming. But he also seems to be interested in de-dramatizing the substances he suspends and contains within glass. He isolates that which ostensibly produces race and gender, what is thought to operate as a kind of biological substrate. Puncturing essentialist myths, he allows the viewer to gaze upon the things themselves – these loaded, regulated substances. He invites us to consider them as components in a broader assemblage that determines their stasis and circulation. He temporarily stops the flow and asks us to consider their place in a larger network that shapes their suspension and containment; he builds structures for holding in view those substances that so often determine how structurally held one is.

At the conclusion of an Art21 short film profile about his work, he discloses a bit about his practice, his work ethic, and his analyst, reporting,

My therapist says that I’m so familiar with oppression that danger and risk and oppression make me feel at home, so I slave myself away in the studio or, like, I deprive myself of pleasure because I’m not oppressed as a queer being here, [laughs] so I oppress myself now [laughs], cause I can’t go back if I fail, you know. [8]

Fan is describing something familiar: How it feels when the loophole of retreat becomes pressurized. When the atmosphere of violence is internalized. When that which had promised a possible future, a form of escape, some space to be and work more freely, comes to feel oppressive. When you find yourself reproducing conditions of unfreedom even within an environment that mostly holds. Another theme in Fan’s work: that it is the wound that produces beauty. That beauty – in the sublime sense – always contains a grotesquery, a mark of harm or disruption.

Ceramicist Nicki Green is similarly concerned with phenomena of mutation, transformation, and flux and with the production of holding environments. Such environments appear in Green’s work as vessels (crocks, tubs, pitchers). In Fan’s work, the non-porosity of glass enables the silicone suspension of substance – a kind of snow-globe effect, the production of a contained environment in miniature. It takes a more elaborate process to render ceramics nonporous, requiring glazing in addition to firing, and Green often only partially completes this process. In doing so, she refuses the injunction that a ceramic vessel must be watertight; instead, she builds – and sometimes, literally pedestalizes – leaky vessels, imperfect (broken, sutured) containers. In a 2018 work, Mikveh for Mycotheology, she reinvents a vessel for the Judaic ritual of purification via immersion in water. In this piece, a tub is broken into 24 pieces, with the lines of cleavage radiating from a central axis in the center of the basin. The tub has been sutured back together with epoxy, hardware, and felt washers, but it still sits in two halves. A Star of David is emblazoned on the floor of the basin, riven in two. The interior of the tub is glazed; the exterior is left porous. Along the walls of the tub, beneath circular forms that appear to be lunar phases, circle sacral-seeming androgynous figures, some harvesting mushrooms, others with their faces turned to the sky and arms upraised in the form of a priestly blessing. Healing work is happening, aided by the mycorrhizal interconnections that root and stitch together both the gathered mushrooms and the scene itself. Green – trans, Jewish – is meditating on the consequences of long histories of ritualized and systemic gender segregation, the incompletion and ongoingness of repair, and the difficulty of piecing together a broken holding environment. The piece seems to ask what it would take to be able to immerse and arise transformed, together. It seems to raise questions I share: What is the holding environment that would need to be built to transform and sustain collective trans life chances? What are the resources we have? The immersive vision is no Wim Hof-style endurance trial, though it is laborious. The process is already underway. The work is collective, imperfect, ongoing.

Hil Malatino is an assistant professor of women’s, gender, and sexuality studies and philosophy at Pennsylvania State University. He is the author of Side Affects: On Being Trans and Feeling Bad (University of Minnesota Press, 2022), Trans Care (University of Minnesota Press, 2020), and Queer Embodiment: Monstrosity, Medical Violence, and Intersex Experience (University of Nebraska Press, 2019).

Image credit: 1. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., public domain; 2. Courtesy of the artist, photo CE; 3. NASA image by Jeff Schmaltz, public domain; 4. Courtesy of the artist and Kohler Co.; 5. Courtesy of the artist and Empty Gallery, Hong Kong

Notes

| [1] | Callum Angus, “Rock Jenny,” in A Natural History of Transition (Tio’tia:ke [Montreal]: Metonymy Press, 2021), 17–28, 27. |

| [2] | Ibid., 25. |

| [3] | Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, “The Weather in Proust,” in The Weather in Proust (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), 3, 4. Further citations of this work are given in the text. |

| [4] | Steven Swarbrick, “The Weather in Sedgwick,” Critical Inquiry 49, no. 2 (2023): 165–84, at 177. |

| [5] | Eric A. Stanley, Atmospheres of Violence: Structuring Antagonism and the Trans/Queer Ungovernable (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021), 27. |

| [6] | C. Riley Snorton, Black on Both Sides: A Racial History of Trans Identity (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017), 27. |

| [7] | Torrey Peters, Detransition, Baby (New York: Penguin Random House, 2021). This and the following quotations are all from pp. 319–20. |

| [8] | By “here” Fan means New York, as opposed to his birthplace of Hong Kong. See “Infectious Beauty: Jes Fan,” May 20, 2020, part of the New York Close Up series from Art21, digital film, 8:57. |