UNDERSTANDING PSYCHIC LIFE WITH MELANIE KLEIN Amy Allen in Conversation with Isabelle Graw

Karla Black, „Story of a Sensible Length“, 2014

Isabelle Graw: Your book Critique on the Couch: Why Critical Theory Needs Psychoanalysis (2020) updates and improves critical theory with Melanie Klein in a very interesting way. You start by criticizing Jürgen Habermas and Axel Honneth for what you call their “rational model”: how they tend to underestimate the uncontrollable nature of the unconscious and how they also downplay the role of aggressions in social (or intersubjective) interactions. Could you explain why critical theory can benefit from incorporating the lessons of Melanie Klein’s metapsychology?

Amy Allen: First of all, as your question already makes clear, when I talk about critical theory in this book, I’m really thinking about the Frankfurt School tradition. In other intellectual contexts, it might seem strange to say that critical theory needs to reengage with psychoanalysis, because, for example, Lacanian psychoanalysis has had a huge impact on critical theory broadly construed. But my book is trying to make a more focused intervention into the relationship between psychoanalysis and the Frankfurt School. The core issue is the intractability and persistence of irrationality and unreasonableness in human, personal, and social life. I’ve always liked the distinction that Seyla Benhabib makes in her book Critique, Norm, and Utopia (1986) between the explanatory-diagnostic and the anticipatory-utopian aims of critical theory. Critical theory is distinctive as an approach to social theory because it has these two aims, which are seen as informing one another. And to me, psychoanalysis is important for both parts of the project. But the initial payoff of psychoanalysis, for me, is on the explanatory-diagnostic side because it enables us to make sense of the persistent and intractable irrationality and unreasonableness that seem to forever be disrupting our plans for emancipatory futures. What fascinates me so much about Klein specifically is that she’s situated right in between drive-theoretical approaches to psychoanalysis and more relational approaches. She’s the forerunner of the whole object relations school, and there is a deeply relational aspect to her work. But she’s also a drive theorist, which means that the duality of the life and death drives, their fundamental ambivalence, and their persistence in organizing psychic life are fundamental to her work as well. And that makes her approach quite unique.

IG: For me, it is very convincing how you demonstrate Klein’s theory to be relational through and through. You point to how Klein understands the self as socially and intersubjectively constituted. And even the drives in Klein are, as you call them, “relational passions.” You also argue that it is because of this relational dimension of her theory that it is so useful for critical theory. Because critical theory, and the Frankfurt School in particular, presupposes that social relations have a strong impact on subjects, that subjects are formed by a capitalist rule, so to speak. You also underline how Klein’s model is “intrapsychic and intersubjective” at the same time – namely, that it is able to consider internal psychic and external intersubjective processes as being interrelated. Could you explain why this emphasis on the interdependence of intrapsychic and intersubjective developments is so useful for critical theory?

AA: Sometimes critical theorists are suspicious of psychoanalysis because they consider drive theory to be a biologistic, reductive account of human behavior. And we critical theorists are committed to thinking of human beings as socially constituted, right? So, drive theory and critical theory just don’t seem to go together. Although I think we have to be careful about conflating biology with biologistic reductionism, I do take this worry seriously. But what’s distinctive about Klein is that, for her, the drives are social through and through. Even though Klein’s starting point for developing her version of drive theory is Sigmund Freud’s late distinction between life and death drives, she doesn’t really take on board the speculative biology that Freud uses to articulate the death drive. For her, the death drive is simply primary aggression, and aggression is understood in relational terms: it’s about relating to other objects destructively or aggressively. This idea stems from one of Klein’s core beliefs: that the human psyche is object-related from the start. This brings me to your question about the intrapsychic and the intersubjective, because even as we are object-related from the very beginning, we also relate to our objects through the lens of our own phantasy and projection. Thus, the two dimensions, the intrapsychic and the intersubjective, can’t neatly be separated. The relation to the actual other person is crucial for the development that Klein has in mind, but that relation is always mediated through phantasy. That’s what is so fascinating about her account. Her reconceptualization of drive theory and her emphasis on aggression and phantasy allow her to offer a rich and deeply ambivalent account of intersubjectivity – much more so than the version of intersubjective or relational psychoanalysis that informs, say, Honneth’s engagement with psychoanalysis.

Donatello, „Madonna col Bambino“ (Madonna and Child / Madonna und Kind), ca. 1414

IG: In your book, you criticize Honneth’s theory of recognition because – to quote you – he “obscures the fundamentally ambivalent character of object relations” by “purifying the early infantile fusion experience,” thus leaving out aggression, ambivalence, or power relations in his model of recognition. When I read this, I had a rather speculative thought: maybe Honneth opted for this model of an early infantile fusion experience that doesn’t allow for aggression, ambivalence, projection, and all these other more negative experiences because he is positioned as a white heterosexual man in academia, which means he might be less exposed to those aggressions, ambivalences, and experiences of rejection that someone like Klein may have endured. Perhaps there is a gendered dimension here?

AA: It may be that my criticism of Honneth on this point is partly rooted in my own experience of motherhood. I do think that Honneth’s somewhat idealized conception of the mother-infant relationship is harder to sustain once you’ve parented infants and especially toddlers. But that’s as far as I would go in that direction. I prefer to be cautious here because I can think of a lot of theorists who are positioned as white heterosexual men who would be skeptical of Honneth’s emphasis on fusion. I would probably say instead that Honneth’s reading has more to do with his Hegelianism than his gender. His account of recognition seems to be motivated by a certain understanding of integration, where integration entails overcoming ambivalence rather than accepting it.

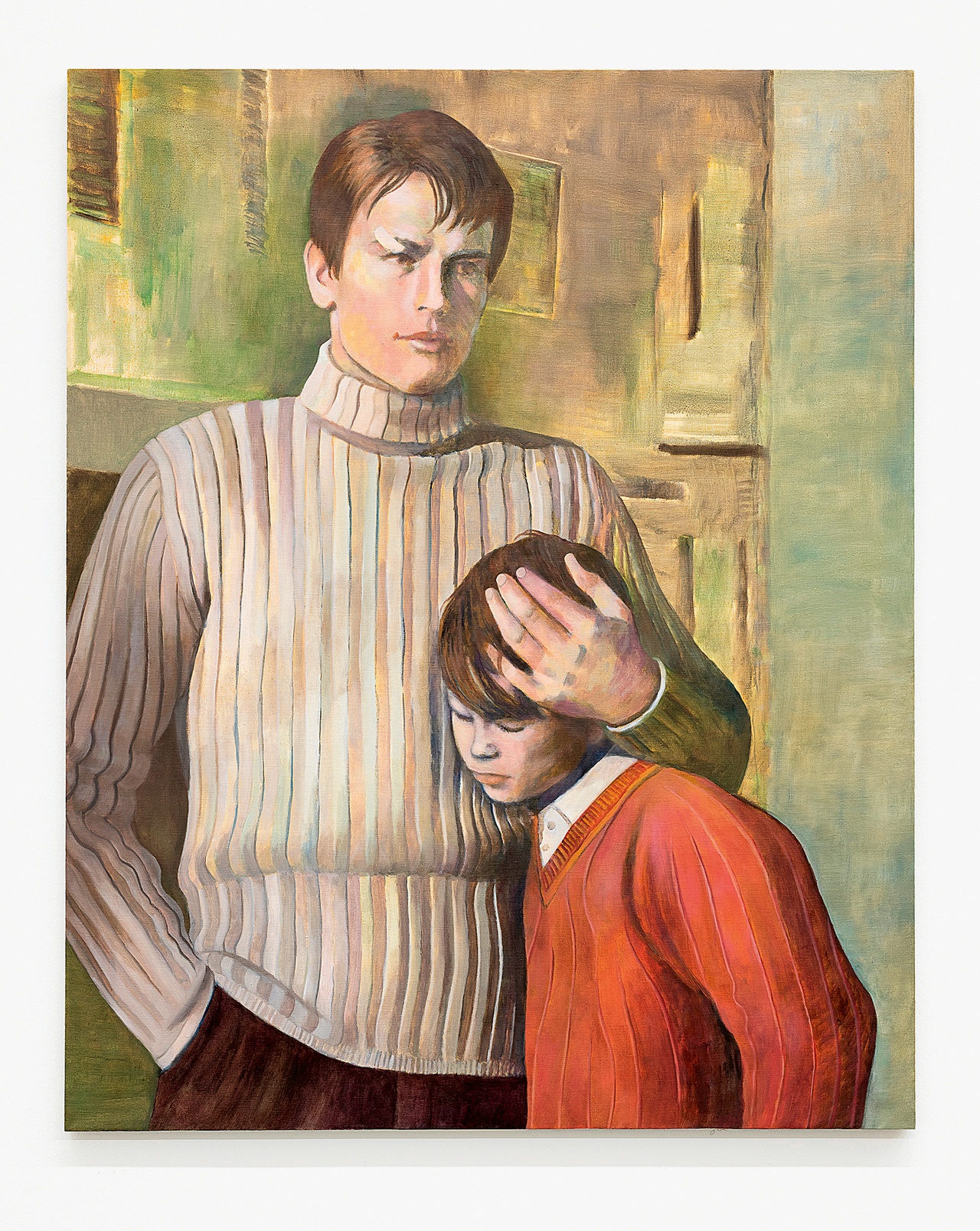

IG: Yes, and there also have been male artists, Donatello for one, who acknowledged the existence of aggression and ambivalence in the mother-infant relationship in their work. There was an incredible Donatello show recently at the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin full of interesting mother-child representations. Next to depictions of a symbiotic relationship, a holy union, you also saw an omnipotent infant who either violently tries to separate from his mother or enacts aggressive gestures toward her. Donatello might have been a Kleinian avant la lettre! Klein is also famous for having come up with what you call a “positional” model. For her, there are basically two psychic positions that we repeatedly inhabit during our lifetime: On the one hand, there is the famous “paranoid-schizoid position,” which results from persecutory fear and consists of polarizing and splitting between an all-good and an all-bad object – the so-called “good” or “bad breast.” And, on the other hand, there is what Klein calls the “depressive position,” which is a more melancholic condition that allows for loss and mourning and integrates ambivalences. Now, in Klein’s view, the depressive position is preferable – even though it is, as you say in your book, no picnic either. You underline how her positional model is superior to developmental approaches in psychoanalysis, such as Freud’s. Could you explain this more in detail?

AA: That’s a complicated story. Freud quite famously articulated this model of psychosexual development that proceeds through various stages – oral, anal, phallic, and so on. This model obviously raises lots of concerns about the relationship between psychoanalysis and sexual normalization – concerns that have played out in both psychoanalytic theory and practice and that have been discussed at great length by feminist, queer, and trans theorists. I would argue that Klein’s positional model is preferable in that it doesn’t depend on this sort of developmental trajectory and hierarchy. Now, we have to be careful here. Klein herself was a good Freudian analyst, and it’s quite clear that she fully accepted his developmental psychosexual story; in fact, she deployed that model frequently in her clinical writings and case studies. My point is simply that her positional model doesn’t depend on that developmental story. Indeed, the paranoid-schizoid and depressive positions come into play in the first year of life; as such, they precede the later account of psychosexual stages. Because she’s talking about these very early psychic stages, her model is not conceptually dependent on this later developmental story. A related issue I’m really interested in is how Freud’s developmental story is also connected to his embrace of theories of social evolution. His developmentalism leads to a very problematic use of the notion of the “primitive,” which for Freud refers both to a kind of archaic psychic state and to so-called primitive or undeveloped societies. Some of Freud’s best-known work in cultural theory articulates this developmental story at a social level. [1] And that’s where part of my interest in thinking through this intersection of psychoanalysis and critical theory lies. How can we articulate different models of what we might want to call maturity, models that don’t depend on these problematic assumptions about social evolution away from a state of “primitivity”? I don’t want to deny that there’s some kind of developmental goal or aim entailed in Klein’s account of the depressive position, because she does in fact think it’s an achievement.

Toys used by Melanie Klein / von Melanie Klein genutztes Spielzeug

IG: Yes, and she also considers the depressive position to be achieved after the paranoid-schizoid one, if one is lucky.

AA: Exactly. And there are better and worse ways of inhabiting and working through the depressive position. So, yes, there is a notion of a developmental achievement or goal in Klein, too, and thus an account of maturity. My point is simply that Klein’s positional model is not articulated as a series of stages that maps onto a series of historical stages from “primitive” to scientific, secular societies. There’s a different way of thinking about individual psychic development in Klein that is not conceptually bound up with these problematic developmental ways of writing history. That’s a promising feature of Klein’s account. Moreover, even though she views the depressive position as an achievement, and she tends to talk about the paranoid-schizoid position more negatively, there are also those Kleinians who emphasize the value of the paranoid-schizoid position.

IG: Maybe the paranoid-schizoid position has potential especially for artists, but we will get to that later. Psychoanalysis has recently been scrutinized by many authors for its heteronormative assumptions and its homo- as well as transphobia. In your book, you argue that Klein’s metapsychological and positional model avoids normative conceptions of gender and sexuality – so, precisely those conceptions that psychoanalysis is often criticized for. You only hint at that in the book, and I would love for you to elaborate a bit further on this point, because this is why many of my colleagues who are invested in queer and/or trans theory are not so interested in psychoanalysis.

AA: This is related to the point that I just made, which is that the development from the paranoid-schizoid to the depressive position takes place, for Klein, in the pre-Oedipal phase. Indeed, this transition occurs in the first year or even the first few months of life. Thus, even within the psychoanalytic framework, the move to the depressive position occurs at a moment before any of these normalizing accounts of psychosexual development get off the ground. I think this is perhaps part of the reason why Klein’s work has been quite informative for queer theory – for example, in the work of Eve Sedgwick and Judith Butler. I don’t think it’s an accident that these thinkers have turned to Klein. She offers a complex and interesting model of psychic life and a notion of the unconscious that doesn’t have as much of the normalizing baggage as other psychoanalytic accounts have. Now, one exception to that – and it’s an important exception! – is the breast. You might say: Well, wait a minute, her whole account is based on the normalizing assumption that the formative, primary object relation of the infant is with the mother. She is making assumptions about how gender and sex and motherhood all line up …

IG: The caretaker, for her, is assumed to be a mother. But since the breast is a partial object, its role can be played by others as well.

AA: That’s the key, exactly. Klein herself tended to assume that the mother was going to be a biological female. But once you think about her understanding of the breast as a partial object, then you can think about how that role could be occupied by other different types of bodies and not understood in such constrained, normalizing ways. There’s even one instance I’m aware of in Klein’s work where she says the breast should be understood in terms of its symbolic function of providing nourishment and love and gratification, and that this function could be fulfilled by someone holding a bottle as well. That’s a very important moment in her work, one that opens her account up to a non- or even anti-essentialist reading. [2]

IG: Her model has the potential to be de-biologized, de-essentialized … The potential is there, even though when I reread Klein for our conversation, I was also struck by the fact that the infant is always “he.”

AA: Right.

Jagoda Bednarsky, „Shadowland (Scape)“, 2020

IG: Allow me to come back to what you described as the Habermas/Honneth emphasis on “rational insight.” You seem to distance yourself from the idea that there needs to be rational understanding for critique to happen. And what you set against the virtue of rational insights is the psychoanalytic model of transference that you consider much more useful for critique. Could you explain why you consider transference – the analysand projecting feelings of love, hate, aggression, etc., onto the analyst – as a model for critique? And what kind of critique would result from transference – could it be social critique? Because if we take the dynamic between the analyst and the analysand as a model for critique, don’t we run the danger of underestimating the power of those external social and economic structures that actually limit our possibilities for change and intervention?

AA: These are great questions. Habermas’s early work Knowledge and Human Interests (1968) argued that psychoanalysis provides a compelling model for critique. His point was not that we engage in critique by going into psychoanalysis, but rather that there’s something about psychoanalytic method that can be helpful for understanding critical method. That has always struck me as a really interesting and fruitful idea. But the concern I have is with how Habermas understands psychoanalytic method, namely, as a process of rational enlightenment. My point is not that rational insight is irrelevant to the psychoanalytic process; rather, it’s that rational insight by itself is not only insufficient but can also become a mode of psychic defense, a kind of rationalization that undermines the prospects for genuine transformation.

IG: Also, if I rationalize my behavior in psychoanalysis, I am under the illusion that it is possible for me to get things under control by rational insight …

AA: Exactly. So what struck me when thinking about this way of spelling out the analogy between psychoanalytic and critical method was that it downplays the role of the transference. Psychoanalysts from Freud through Klein to Lacan are very clear that transference has to precede rational insight. In other words, you have to have a certain kind of transference relationship in place in order for rational insight to, as Lacan says, hit home. Only then can a psychoanalytic interpretation or insight actually have a transformative effect. And so, I wondered, what happens if we take the role of transference seriously? What would that mean for the analogy between psychoanalysis and critique?

IG: And the transformation first occurs in the transference relationship between analyst and analysand and not only on the level of rational understanding.

AA: Right. But I was really stuck for a while because I couldn’t think of what transference would mean for social critique. And then I read some of Jonathan Lear’s work on transference. And for me, that was really helpful because Lear makes the distinction between relational and structural transference. A lot of times when we think about transference, we’re thinking about the relational model. In that model, I transfer my attachment to my primary object, usually my mother, onto the figure of the analyst, creating an affective bond that facilitates the analytic process. Admittedly, it’s very difficult to see how that conception of transference is relevant for social critique. But the structural account is different. As Lear explains it, structural transference is about how, within the context of analysis, the analysand comes to experience their way of relating to the world as a way of relating to the world that they themselves have had a major hand in constructing.

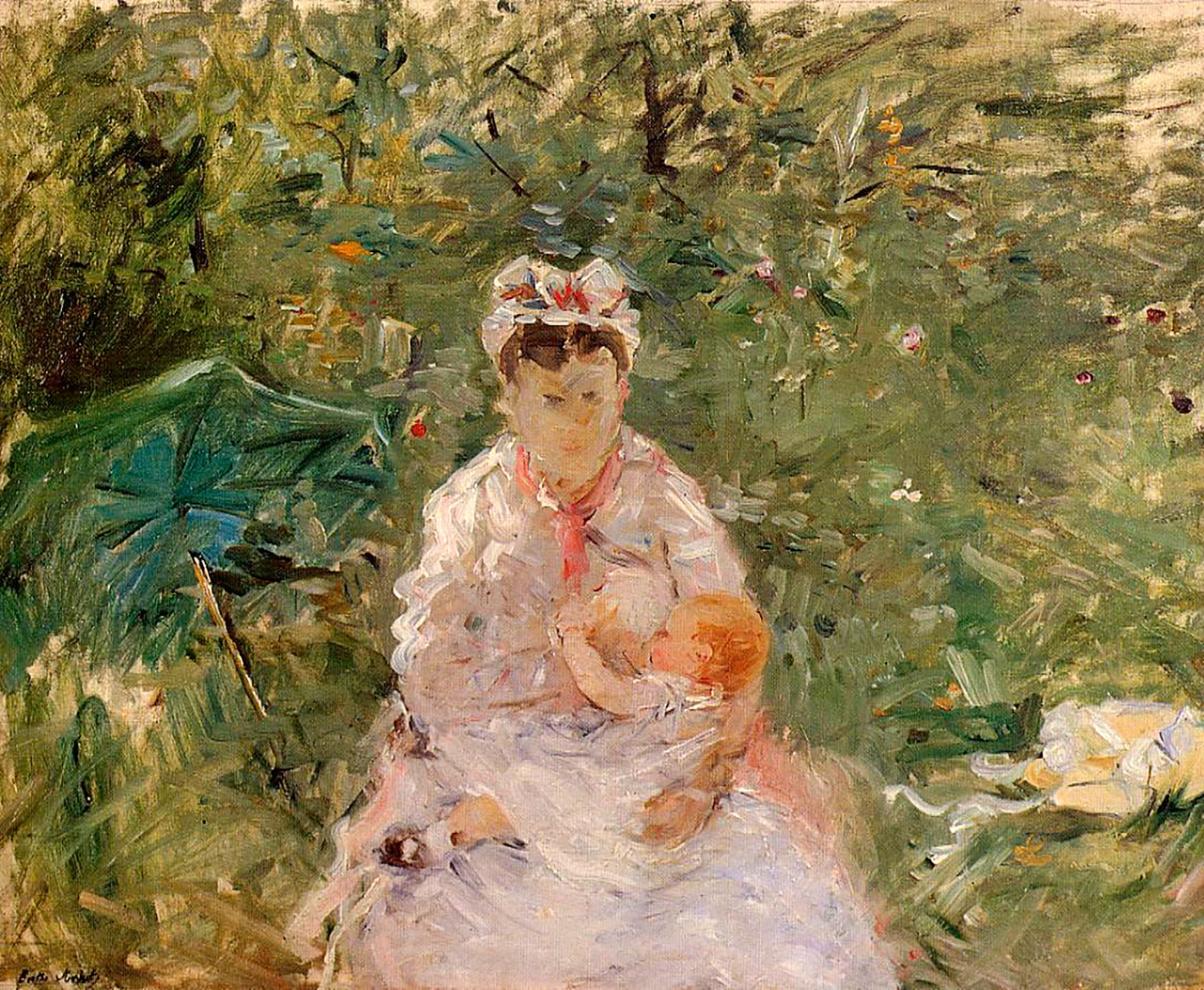

Berthe Morisot, „La nourrice Angèle allaitant Julie Manet“ (The wet nurse Angèle feeding Julie Manet / Die Amme Angèle stillt Julie Manet), 1880

IG: But doesn’t this idea overestimate the hand? How about given conditions that we don’t have a hand in making?

AA: I want to come back to that because it’s very important. But first let me finish spelling out how structural transference works: namely, as a kind of defamiliarization and denaturalization that opens the analysand’s experience up to practical transformation. And when I first read that, I thought: That sounds exactly like the way Foucaultian genealogy works! That genealogy also works through a defamiliarization and denaturalization of a certain taken-for-granted social organization and set of experiences – a process that also has an experiential and transformational effect. That was the moment I realized how structural transference could be useful as a model for social critique. To your question: Does this model end up overestimating the hand that the individual has had in constructing their world? Not necessarily, because once we transpose this model into the realm of social critique, we are not talking about individual agents anymore. We’re talking about social actors more broadly who have collectively had a hand in creating and sustaining certain institutions and practices. Like structural transference, problematizing genealogy enables us to reorient ourselves in relation to those institutions and practices, to experience things that seem intractable and unchangeable as the changeable products of human activity. But only through collective social engagement.

IG: This would mean that we completely disconnect transference from this notion of it resulting from a tête-à-tête between two people – the analyst and the patient.

AA: Indeed, the question for this analogy is: In the case of social critique, who are the figures engaging in the transference relation? On this point, I follow Robin Celikates’s account of critique as social practice. The relationship is one of ongoing dialogue between social movements and social critics. That’s where the dialogue that’s modeled on psychoanalytic dialogue is taking place. But what this is supposed to spark is a different way of relating to the social world, a defamiliarization and denaturalization that enables us to engage in the work of social transformation.

IG: But doesn’t this operation of defamiliarization presuppose a sort of implicated but still reflexive distance? I was struck by your saying in the book that reflexive distance is a rationalist illusion. I was thinking of Luc Boltanski and his book on social critique, where he talks about reflexive distance as a “necessary illusion” – a position that acknowledges its illusory character but that has to be taken for critique to happen.

AA: It may be that I don’t distinguish carefully enough between rationality and reflexivity in the book. That said, my considered view is that the transference model, which is about a kind of reorientation of our own experience of the world, needs to connect up with rational critique in the right way. Is it possible for reflexivity and rationality to be completely purified of all entanglements with power and domination? No, I don’t think so. But does that mean we have to give up on rationality and reflexivity altogether? No, it doesn’t.

Birgit Megerle, „Care IV“, 2023

IG: That’s interesting because you often underline in the book how Klein aims for a psychic state where we narrow the gap between phantasy and reality, between our phantasmatic perception of others and who they really are. But I wonder: Can we ever know how someone really is? And more so: Can we assume something like a given objective reality? Isn’t that a slightly objectivist assumption? Can we ever distinguish our perception of reality from how reality really is? Isn’t the border between our phantasmatic perception of reality and social reality, by definition, completely and hopelessly blurred?

AA: First of all, I am not assuming any kind of metaphysical realism. I’m completely with you on your concerns about our access to objective reality – I’m a good Kantian on that point. I believe that our perceptions are always filtered through our own mental structures such that we don’t have access to the things-in-themselves. So what do I mean when I call Klein’s conception of the person realistic? This refers more to a political – as opposed to a metaphysical or an objective – realism. To say that her conception of the person is realistic is just to say that she takes the persistence of aggression – and the will to domination and power that goes along with it – very seriously. But what could it mean to close the gap between our phantasied projection of another object, another person with whom we’re intimately related, and who they “really” are? It is important to emphasize that, for Klein, this gap can never fully be closed: we can’t know with certainty or finality whether our experience of someone else, their motivations, their intentions, or their state of mind is true or not. To say that this gap could ever fully be closed would be to say that we could eliminate the workings of the unconscious and the role of phantasy in filtering our perception of other people. And that would, of course, make no sense from a psychoanalytic point of view. But at the same time, there are moments when our interpretation of other people’s motives is more bound up in our own fears and anxieties. And there are other moments when we we’re able to calm down some of that internal anxiety and meet other people closer to where they are.

IG: I agree with you – it’s a gradual thing. My therapist always encouraged me to see the other person as how they really are. And of course, I questioned that, but I also knew what she meant because I projected so much. So, it’s more about projecting a little bit less, right? And it’s not about stopping projecting and producing phantasies altogether because that’s impossible.

AA: Exactly. To be sure, there is some debate about how to read Klein on this point. Some people would say when Klein talks about object relatedness, she’s only talking about our relationship to internalized objects; she isn’t actually talking about other people at all. I read Klein differently because I think that, for her, the challenge is all about the movement from the internalized phantasy object toward the other person. The internalized bad breast and good breast are based on an external object or some figure – for Klein, it’s the mother/caregiver and the physical breast or bottle. This means that the internalized objects are rooted in our experience of a primary relationship. And Klein is quite clear that the actual relationship with that primary caregiver impacts and facilitates the child’s progression from the paranoid-schizoid phase into the depressive phase. It’s not as if the relationship with the other person doesn’t matter, it does …

IG: I would even say, and you make this clear in the book, that in Klein’s model, interactive projection and internal introjection go hand in hand.

AA: Exactly!

IG: As much as you might project onto an object, you also introject it. And Klein assumes an interactive dynamic between our external experiences with others and our psychic inside. And I think that absolutely renders her model so valuable to our current moment.

AA: In the book, I talk about how Klein rejects Freud’s understanding of primary narcissism because we are interactive and engaged in these relationships all the way down. But it’s true that there are residual elements of the theory of primary narcissism in Klein’s work. For her, we all start out more overwhelmed by phantasy, more wrapped up in our own intrapsychic world. Part of the achievement of moving into the depressive position is getting closer to the other, integrating and modulating the extent of that projection and phantasy in our relationship with others. In the process, we come to see them as more complex and whole objects, as she would say, rather than to either demonize or idealize them.

IG: But couldn’t it be that an object, or rather a person that one encounters, is actually “bad” and does inflict harm, and for this reason one has to draw a line? So couldn’t the paranoid-schizoid position – splitting between an all-good and all-bad breast – become an adequate response in certain circumstances?

AA: I don’t want to deny that as a possibility. The Kleinian idea of thinking of other people as whole objects, of integrating the good breast and the bad breast, is about seeing another person as having good and bad aspects or elements. And it is also about accepting that one’s relationship to that person is one of love and connection but also one of hatred and aggression. Especially in our most intimate relationships, these two things are often very difficult to distinguish. So even if the other person is doing something you experience as horrible, this is still a whole person, and from their perspective the way they’re acting makes sense. Does that mean we have to, in every case, orient ourselves to people that way? Not necessarily. But I do think we need to worry about the tendency to assume that any time someone behaves toward us in a way that we find harmful, that they must therefore be evil and completely unredeemable.

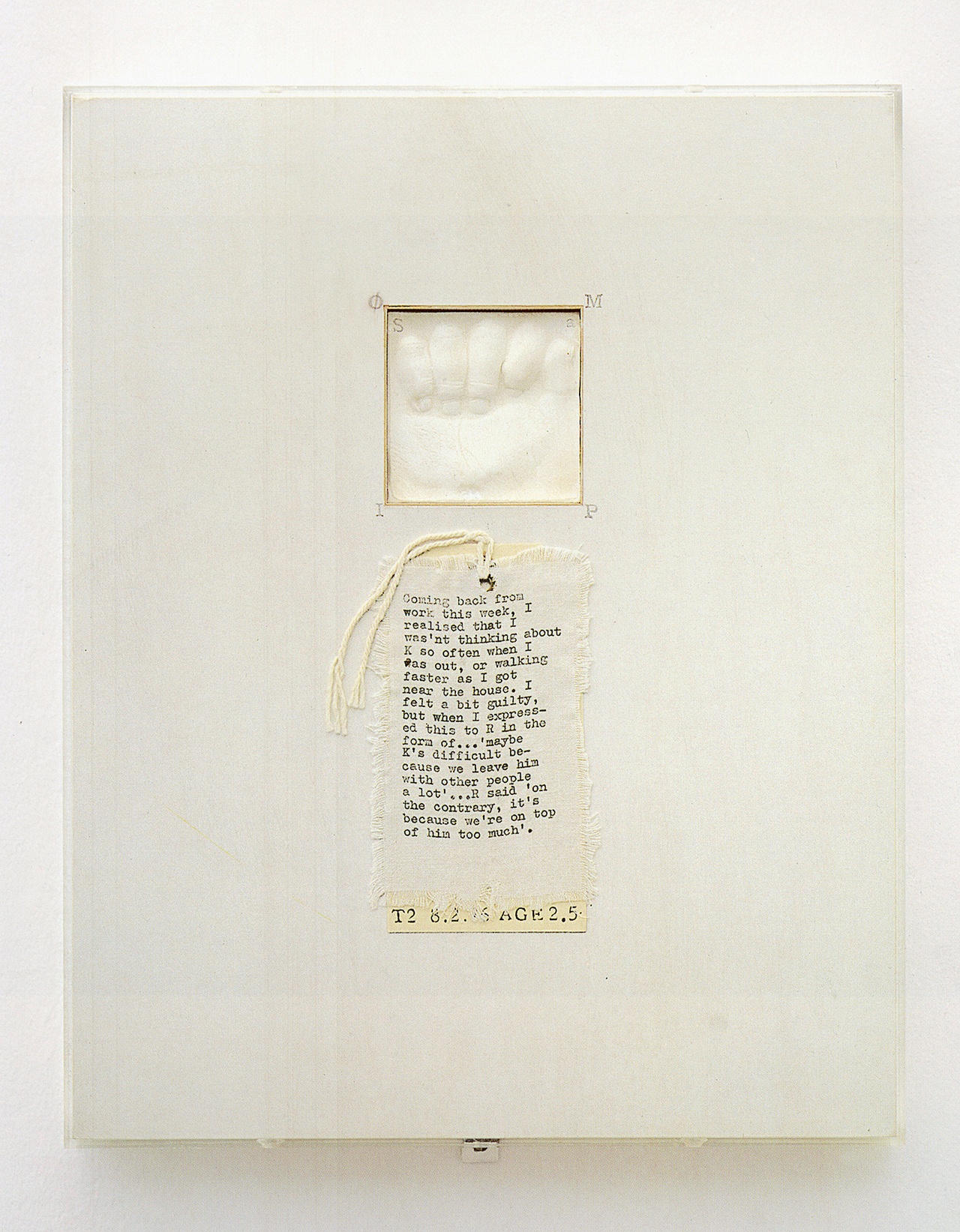

Mary Kelly, „Post-Partum Document: Documentation IV, Transitional Objects, Diary, and Diagram“ (detail), 1976

IG: I don’t want to sound like someone who wants to rescue the paranoid-schizoid position at all costs. But what about our encounters with, say, white supremacists? There’s no common ground. There is a kind of “us” versus “them” situation implied here, and there is reason for polarizing and splitting. Or should we try to understand what led them to their hateful and inhumane views and see them as whole persons? Should we try to understand Vladimir Putin? Or is it at times a political necessity that we draw a line and do not talk to the representatives of the Far Right? In Germany, there has been a whole debate about this, whether “Mit-Rechten-Reden” [talk to the Right] makes sense or not. And I think there can be strategic and situative instances where the paranoid-schizoid approach can be justified.

AA: I think that’s true. I mean, at least I can imagine that there could be situations like that. I keep thinking of that old saying: “Just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they aren’t after you.” I think the question of how to relate to, let’s say, Trumpists or white supremacists, white nationalists … well, it’s complicated. But I guess I lean more in the direction of thinking that we should not accept their views at all, we should completely reject their beliefs and principles. But that’s different from pathologizing and demonizing the people who hold them.

IG: So, in a way, it’s a bit similar to what Natalie Wynn proposes in her YouTube video on canceling: critique instead of canceling.

AA: Yeah, maybe. Like it or not, our political system is such that we have to engage with these people. I’m really influenced by some of Nancy Fraser’s work on this. [3] She argues that there are some productive possibilities for a political realignment between some Trump voters and more progressive left-wing movements around economic issues. If that’s correct, it’s not in our interest to engage in pathologizing and demonizing everyone who has supported Trump simply because they supported him. This is completely consistent with insisting that we find racist, xenophobic, misogynistic, and transphobic views abhorrent and unacceptable; I’m not at all suggesting that we should be willing to accommodate or even reconsider these commitments. But if we might be able to find common ground with some folks who support right-wing populist movements for different reasons, and this might enable us to mount a successful challenge to the current neoliberal order, that would be a good thing. But this will never be possible if we demonize everyone on the other side. I’ve also been really inspired by some of Noëlle McAfee’s recent work on democratic deliberation. [4] McAfee cites empirical research that looks at what happens when people engage in deliberation and conversation with those who are from the extreme other end of the political spectrum. And it’s very interesting: people don’t necessarily change their minds about their views or political beliefs on the basis of those conversations. But they do change their views about the other people who hold the opposing view. It’s not that they condone or excuse the others’ views, but they do come to see how, given the other person’s experience and perspective on the world, they might arrive at those views. That’s a model of democratic deliberation that can have some traction in an incredibly polarized environment. It doesn’t get us all the way to where we need to be, but it might be an important first step to getting beyond this paralyzing political polarization of our current moment.

IG: This is also interesting from the perspective of an art historian. When I look, for instance, at the history of the historical avant-gardes, I encounter an artistic field that was deeply polarized. It was crucial for each avant-garde movement to presuppose enemies and opponents. One could argue that the operating system of the avant-garde is paranoid-schizoid. Of course, there are also examples of artists who have made work from the depressive position. I recently saw Joan Mitchell’s paintings in Paris, and many of them result from the labor of mourning. But when we consider social media – the network platform of the art world – people here are splitting and polarizing like crazy. And for the creative process as well, it can be necessary to split from an assumed consensus, to polarize against the old guard and to rage against given assumptions in certain historical moments.

AA: This goes back to something we touched on earlier. Klein herself tended to be mostly negative about the paranoid-schizoid position – she saw it as something to be continually overcome. But some contemporary Kleinians, like Thomas H. Ogden, have argued that there are virtues of the paranoid-schizoid position. [5] It enables a kind of breaking up of ossified structures and an iconoclasm that can be really important for opening up space for something new. There are moments where that is really what’s needed.

IG: Maybe it’s okay to go through a paranoid-schizoid phase from time to time. But to get stuck in that psychic condition can be a bit tedious and boring and dangerous. But it’s so interesting to think about Klein in terms of art history and art criticism, because as you pointed out, she really puts a lot of emphasis on the role of phantasies. Klein demonstrated how our object relations are mediated, filtered, and distorted through phantasies. And art criticism is, of course, an activity that is all about grasping (and evaluating) objects and their relations. So, it is traversed by phantasies about and projections onto these objects. But, at the same time, art critics are confronted with a certain reality of the objects – objects that talk back to us. I was wondering: What would an art criticism that reflects upon its own phantasies and projections with Klein look like?

AA: I am a complete outsider to the world of art criticism. But I thought what you just said was really fascinating, especially the point about the objects speaking back in a certain way. It takes us back to when we were talking about Klein’s negotiation of the intrapsychic and the intersubjective. There’s an analogous question that comes up a lot in my discipline, philosophy, about the interpretation of a text. There are always elements of phantasy and projection that go into the interpretation of a text. This means that there are lots of different ways of reading texts – especially very complex texts – but does that mean that all interpretations are equal, that anything goes? Well, no, because the text speaks back. There has to be some kind of give-and-take between the creativity of the interpreter and what the text actually says without falling into the idea that somehow the text explains or interprets itself.

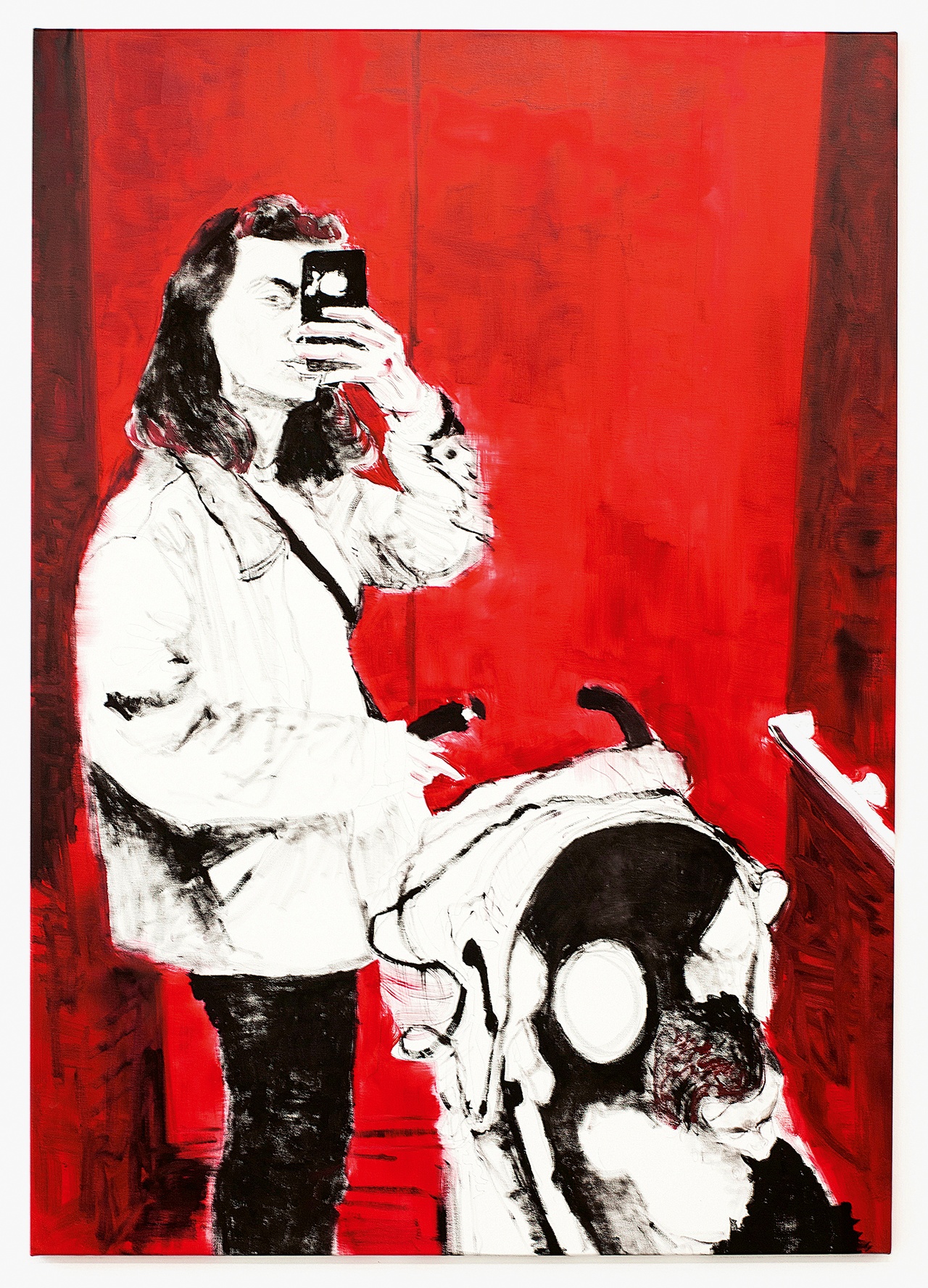

Valentina Liernur, „Selfie con carrito“, 2019

IG: To conclude our conversation, I would like to refer to the theme of Ohnmacht, which is guiding this issue. Ohnmacht is very hard to translate into English. One could translate it as fainting, as powerlessness, or as impotence. But all these English translations don’t capture the nice thing about Ohnmacht, which is that it also refers to a residual power, Macht, in the midst of it. With Klein in mind, one could characterize Ohnmacht as a psychic condition where we depend on others and how this dependency on others marks us from the get-go. One could also think of Klein’s depressive position as having a lot in common with Ohnmacht because it points to ways of coping with this terrifying anxiety that results from our helplessness, from our being at the mercy of others. So, this psychic condition is similar to feelings of Ohnmacht. With this in mind, I wanted to ask you: What kind of agency is at work in Klein’s depressive position? What are the possible actions of a depressive agency?

AA: The idea that a human infant is born helpless and dependent is not unique to Klein – this is an important insight of Freud’s as well. And it has important implications for our psychic lives and our ongoing socialization. Klein gives this idea a particular spin that’s interesting because the dynamics of love and hate that are so central to her work are partly explained by this position of extreme dependency and vulnerability. For Klein, our psychic starting point is a feeling of persecutory anxiety. The infant feels hungry and thinks: Why isn’t the good breast here to feed me? It’s trying to destroy me because it’s not responding to my need.

IG: The infant also experiences fear of annihilation when its mother/caregiver is absent.

AA: Yes. But then this object that the infant feels persecuted and attacked by is also the very same object that the infant loves and depends on and receives nourishment and gratification from. And it’s that push-pull, that oscillation back and forth between these two stances, that’s the characteristic of the paranoid-schizoid position. A principal achievement of the depressive position is the ability to integrate these two stances and thus to experience the object as a whole object. In so doing, the infant comes to realize that these two-part objects that have been split are actually the same – that is, that the same object that I love and am gratified by is also the one that I hate and am frustrated by. That gives rise to a different, depressive kind of anxiety because the infant realizes, Oh, I’ve been lashing out in phantasy and perhaps even in reality against this object. And because of the kind of omnipotence of thinking that is for Klein characteristic of infantile experience, the infant believes they have thereby destroyed this object that they love. This is what then gives rise to depressive anxiety and, for Klein, to the drive for reparation. This is a long way around to answer your question, but I think the starting point of an answer would be: depressive agency is reparative. It is an agency by a kind of integrative impulse, a drive to put objects that have been split back together and to relate to them as whole objects. Crucially, however, integration has to be understood not as assimilation or as a hierarchical, vertical process of subsumption but rather as a deeply expansive way of relating to the other.

IG: In the art world and also in the social sciences, there has been a great interest recently in the notion of repair and reparation, not only from the perspective of postcolonial studies but also from a sociological angle. I wonder whether there could be a connection between this renewed interest in concepts of repair and reparation and the paranoid-schizoid atmosphere that we currently live in. And could there also be a problem in the focus on care and repair/reparation because it implies a denial of the Kleinian emphasis on aggression and all those other destructive impulses that mark the paranoid-schizoid perception of the world?

AA: What’s interesting and compelling about Klein’s account is that, for her, depressive agency is not at all about denying aggression. It’s about being able to withstand the ambivalence that necessarily results from the unavoidability of aggression; therefore, it’s about being able to relate to one’s own aggression and the aggression of other people more productively. In some strands of queer theory that are inspired by Klein, I see a problematic de-emphasis on the inevitability of aggression and the ambivalence that is endemic to the depressive position. But in Klein herself, it’s quite clear: Depressive agency is about accepting and managing aggression more productively. It’s not at all about denying or eliminating it.

IG: How could one conceptualize the ego in the depressive position or the ego in the ohnmächtige position? Because this ohnmächtige ego seems to be an ego that neither gives itself up completely nor is able to completely dominate. It’s kind of in-between.

AA: That’s a nice way to put it. Klein offers a distinctive understanding of ego integration. I mean, this is a complicated point. It’s an important point, too, because, for example, Lacan was famously very critical of Klein for holding onto a notion of the ego that he, of course, thoroughly rejected. For Lacan, the ego was a completely narcissistic structure. But Klein’s understanding of ego integration is totally different from the classical Freudian view of the ego. Ego integration, for her, is about the expansion and enrichment of the ego through the incorporation of more and more unconscious content. It’s a fundamentally expansive model of the ego rather than one of hierarchy or the mastery of the drives. And I think that is related to what you were calling the “in-between.”

IG: But if we assume this weakened ego that is not the master of her own house but also not without agency, there is a danger that you point to in your book – a danger acknowledged by Theodor W. Adorno – that this weakened ego might be easily seduced by fascist temptations. How can one prevent this weaker ohnmächtige ego from opting for fascist scenarios? And how far should its empowerment, its autonomy that prevents it from succumbing to fascism, go?

AA: What I argue in the book is that Adorno gets stuck on this point because he isn’t able to envision a different model of ego strength. For him, ego strength seems to be about mastery and domination of inner nature. What’s great about reading Adorno, but also at times very frustrating, is that there’s a keen attentiveness to and even an intensification of certain contradictions and paradoxes. On the one hand, he’s trenchantly critical of this model of the ego as held together through the internalization of domination or the introjection of sacrifice. On the other hand, without this type of ego strength, we’re at risk of becoming authoritarian personalities. Although I’m sympathetic to those who would say Adorno is just trying to highlight something that’s deeply antagonistic and problematic about our society, at the same time, I find this unsatisfying. Klein offers a different way of thinking about ego strength that perhaps shows us a way forward. The strength of the ego, for Klein, is about its ability to expand and enrich itself and to withstand ambivalence without falling back into splitting and breaking itself up into bits. It actually requires quite a lot of strength and active engagement on the part of the ego to maintain that stance. It’s a lot of work. Splitting and demonizing and idealizing are easier.

Amy Allen is a distinguished professor of philosophy and women’s, gender, and sexuality studies at the Pennsylvania State University. She works at the intersection of Frankfurt School critical theory, contemporary French philosophy, feminist theory, psychoanalytic theory, and postcolonial theory. She is the author of five books, including The End of Progress: Decolonizing the Normative Foundations of Critical Theory (2016) and Critique on the Couch: Why Critical Theory Needs Psychoanalysis (2021), both published by Columbia University Press.

Isabelle Graw is the cofounder and publisher of TEXTE ZUR KUNST and teaches art history and theory at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste – Städelschule in Frankfurt am Main. Her most recent publications include In Another World: Notes, 2014–2017 (Sternberg Press, 2020), Three Cases of Value Reflection: Ponge, Whitten, Banksy (Sternberg Press, 2021), and Vom Nutzen der Freundschaft (Spector Books, 2022).

Image credit: 1. Courtesy Karla Black and Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne; 2. Detroit Institute of Arts, public domain; 3. Courtesy of Wellcome Collection, public domain; 4. Courtesy Michael Neff, photo Hans-Georg Gaul; 5. Private collection, public domain; 6. Courtesy of Birgit Megerle and Galerie Neu; 7. © Generali Foundation, photo Werner Kaligofsky; 8. Courtesy of Valentina Liernur, photo Nacho Iasparra

Notes

| [1] | See Freud’s Totem and Taboo (1913) and The Future of an Illusion (1927). |

| [2] | For further discussion of this point, see Amy Allen and Mari Ruti, Critical Theory Between Klein and Lacan: A Dialogue (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019). |

| [3] | Nancy Fraser and Rahel Jaeggi, Capitalism: A Conversation in Critical Theory (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2018). |

| [4] | Noëlle McAfee, Fear of Breakdown: Politics and Psychoanalysis (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019). |

| [5] | Thomas H. Ogden, The Primitive Edge of Experience (Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson, 1989). |