POLITICAL INCORPORATION Sophia Süßmilch Speaks with Antonia Kölbl on Right-Wing Culture Wars, Affectionate Cannibalism, and Naked Bodies

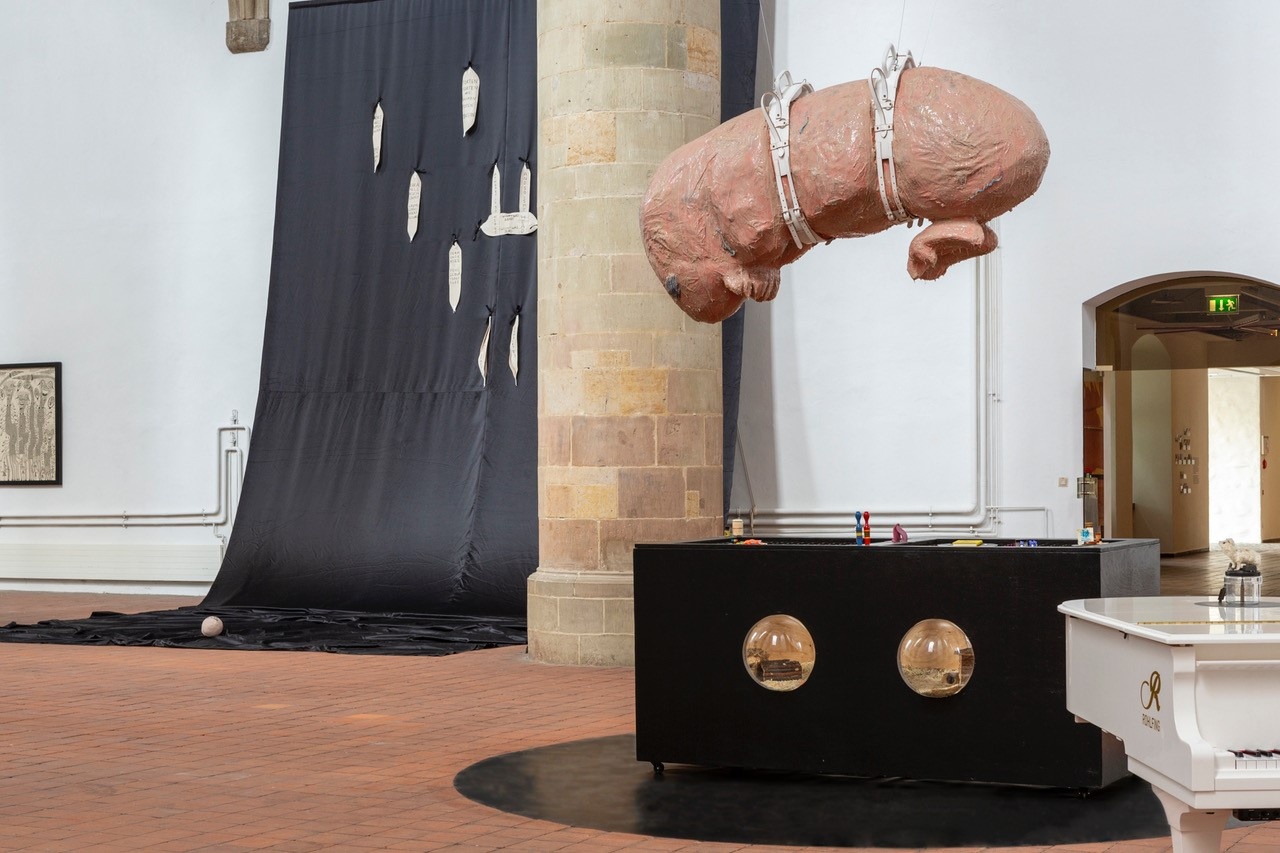

“Sophia Süßmilch: Then I’ll huff and I’ll puff and I’ll blow your house in,” Kunsthalle Osnabrück, 2024

ANTONIA KÖLBL: The title of your exhibition, “Then I’ll huff and I’ll puff and I’ll blow your house in,” which opened with a performance on the evening of June 15 at Kunsthalle Osnabrück, refers to an English fairy tale about the big bad wolf trying to devour three little pigs. In the Grimm fairy tales, the wolf actually has its sights set on a little girl. And Gretel and Hansel have to save themselves from being eaten by a witch. Here, there’s a firmly embedded cultural-historical trope of cannibalism that you take up in your recent works. Nonetheless, on the day before the opening, the newspaper Neue Osnabrücker Zeitung announced that the show was not appropriate for children, [1] and the local branch of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) party followed up by calling for a boycott because you “propagate cannibalistic fantasies,” [2] as the chair of the party’s faction on the Osnabrück City Council, Marius Keite, put it. The German Press Agency report published in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Monopol, Der Spiegel, and Die Zeit led to national headlines – before the performance had taken place or the show had even opened. [3] Had any of the people making these remarks even seen your work at that stage?

SOPHIA SÜSSMILCH: One local editor at the press conference and pre-opening showed up with this totally dismissive, snotty attitude. Why does one have to react to the circumstances of the world with the metaphor of cannibalism, he wanted to know. At first, I jokingly answered that I was trying to find out how scared men would be of me afterward. Then I began explaining to him how I work with the theme of cannibalism, which I’d been thinking about and researching for two years. He just retorted that he’d have done it different. There was just no willingness to engage, to listen. And right at the start, he pitched in with how it’s been known for years that Kunsthalle Osnabrück wouldn’t survive without funding. What an attitude! In the end, it was probably all about the buzzwords: cannibalism, naked female bodies. That was enough to get the show roasted – which is ridiculous, of course. No one from the CDU’s City Council faction came to see the show before calling for a boycott. In their press release, they simply claimed that the show is a family exhibition because the current annual program is called “Kinder, hört mal alle her!” (Kids, listen up!). The two directors of the Kunsthalle, Anna Jehle and Juliane Schickedanz, had in fact invited me and other artists to do work engaging with family, intergenerational conflict, and having children. There was, however, never any discussion of an obligation to be child- or family-friendly. I was probably included because I do a lot of work with my mother. The Osnabrück CDU, with a Trump-like gesture, created this reductive image of my work on childbirth and cannibalism and declared it “misanthropic.” [4] To them, I’m just a pawn in their culture war because they’ve been wanting to shut down Kunsthalle Osnabrück since forever; its feminist management team triggers all kinds of defensiveness in them. [5] I’m still astonished that following this call for a boycott, and for the closure of the exhibition, the national-level CDU didn’t get involved. It genuinely scares me. It makes me suspect they’re still exploring a possible coalition with the AfD, which has been classified as “suspected Far Right” by the Office for the Protection of the Constitution.

Emil Orlik, “Hänsel und Gretel,” 1911

KÖLBL: The fact that the Neue Osnabrücker Zeitung article ends with the one-word sentence “Traurig.” – a nod to the Trumpian “Sad.” – fits the pattern perfectly. Did you have any inkling you would end up being pulled into this kind of culture war? In the satire show Willkommen Österreich (Welcome Austria), the presenters sardonically pointed out that surely “animal-rights activists […] will be every bit as nervous as little rabbits,” because living guinea pigs are part of your show. “I think child protective services will be pretty nervous too,” was your dry response, and that the permission to eat children “still needed to be applied for with the City Council’s cultural department.” [6]

SÜSSMILCH: That was pure satire. It’s a satire show, obviously! And it was the most absurd thing I could say. I eat kids, so child protective services is coming. And what happens? The CDU is all, Won’t somebody please think of the children! What also transpires is people end up losing the plot and calling the veterinary services, who in fact are on our side. We’d already taken precautions, because when it comes to animals, there are a lot of people who are ready to throw down. But in all seriousness, I had no intention of causing a scandal. If people are saying I’m ripping apart taboos, or polarizing: that’s not something I do in my world. There’s people that are shocked just at the body of a naked woman. More than anything, it creates anger. It creates fear.

KÖLBL: It’s far from the first time that right-wing culture wars have pulled child protection into the frame as a means of discrediting and attacking feminist artists, as has been pointed out by, among others, Nina Schedlmayer on her blog Artemisia. [7] But the CDU attack also questions the freedom of art: Verena Kämmerling, the district chair of CDU Osnabrück, who’s a member of Lower Saxony’s state parliament as well, insinuated in her initial statement that exhibitions would need to get official approval. [8] Freedom of art, which is enshrined in the constitution in Germany, was also drawn into debate during the most recent Documenta. Since October 7 and in the conflict over Berlin’s so-called anti-discrimination clause, this discourse has intensified even further. Do you see any connection between those discussions and the actions of the Osnabrück CDU?

SÜSSMILCH: Definitely. But at the same time, I have the good fortune that the Kunsthalle totally has my back. The Candice Breitz situation was entirely different. Her show at the Saarland Museum was canceled after three years of planning, and she wasn’t even informed of the cancellation before it was publicly announced. Her political activism following October 7 had no connection at all to the exhibition. It’s not acceptable for a German institution to use Breitz’s liberal attitude as a Jew against her, to use it as a pretext for no longer publicly exhibiting her art. That’s a political scandal – as is the lack of transparency in the whole affair, right up until today. It’s unsettling that more artists didn’t express their solidarity with Breitz. Showing solidarity with me is a great deal easier to do. Yet public cultural funding is so important: art can only be created if it’s funded. There’s some who’ll be in for a shock when the AfD gets into government and funding gets cut. We’re seeing the beginnings of it with the Senator for Culture and Social Cohesion in Berlin, the CDU’s Joe Chialo. I’m already dreading finding out who’ll be appointed director of the Volksbühne am Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz following the death of René Pollesch.

“Sophia Süßmilch: Then I’ll huff and I’ll puff and I’ll blow your house in,” Kunsthalle Osnabrück, 2024

KÖLBL: Chialo’s treatment of the Oyoun cultural center shows that the threat of politically motivated funding cuts doesn’t just come from the AfD. [9] There’s pressure coming down on public cultural funding that, for artists and other cultural workers, is sometimes of existential importance. Which makes it all the more vital to stake a claim on those resources, to defend them where necessary.

SÜSSMILCH: Another aspect of the current situation in Berlin is that politicians are trying to pressure academics: after the open letter issued by teaching staff at Berlin universities [in support of students’ rights to protest without police repression], Germany’s education minister Bettina Stark-Watzinger of the Free Democratic Party apparently checked whether it would be possible to cancel the funding of all the letter’s signatories. [10] All while neo-Nazis in Lower Saxony were celebrating the summer solstice and the police saw no reason to intervene. [11] I find it wild that neither the Social Democrats nor the Greens spoke up. Nor did the media. I feel like cowardice plays into this. Have they forgot that academic freedom, artistic freedom, and press freedom all go hand in hand? You have to take a stand against fascist tendencies.

KÖLBL: What we’re seeing in terms of cultural politics isn’t just affecting institutions. It’s impacting individuals, too. After the call for a boycott, you received death threats. How do you deal with something like that?

SÜSSMILCH: Most of the press inquiries I got were about the death threats, which makes me angry because women always get pushed into the victim role. If I’d been a man under pressure, everyone would have rushed to the exhibition and would be all enraptured, What a genius! But instead, they’re asking, How do you feel about the death threats, Sophia Süßmilch? Even serious media like you were asking that question. It’s the true-crime effect of sensationalism. We’re used to seeing women as victims. But apart from that: How do I feel? Furious about the behavior of the Neue Osnabrücker Zeitung editor and the actions of the CDU faction. At the same time, I feel intellectually above the whole thing, but sadly that’s not always so helpful in conflicts with the political Right – and that sets off a kind of powerlessness that gets me even angrier. My way of dealing with that is humor. There’s no other way. Otherwise, all that’s left is powerlessness – and I’m not ready to accept that.

KÖLBL: The criticism of my question is absolutely valid – I don’t know for certain whether I’d have asked a man the same question. But I’m not focused on the sensationalist aspect of the death threats, but on recognizing that it’s not just a case of a nasty email, but a legally punishable threat of violence – and ultimately, ignoring that doesn’t deliver justice to those affected, does it?

SÜSSMILCH: Yeah, it’s really intense. Especially as so many of the people writing this stuff to me claim to be women. Luckily, this wasn’t the first shitstorm I’ve had to deal with. Another one, in 2019, hit me harder, as I wasn’t really established yet and was in an uncertain phase with my work. People were already writing death threats to me back then. “Why don’t you make a performance with a toaster in the shower?” – that kind of thing. After that, I switched everything to private. Another thing that helps me is to repost disparaging messages I get – DMs, emails, comments – on Instagram. Publishing something that had been personally directed at you keeps it at a distance. Sometimes, though, the online hate can make you lose all faith in humanity. We’ve seen time and again how online violence can lead to real-world violence. It’s something I’ve thought a lot about recently. I’ve realized once again that it’s not as easy to distinguish good and evil in people as it is in fairy-tale characters. Those are the kinds of ambivalences that my exhibition seeks out. I definitely have something evil within me, too. Back when I was at school, for instance, I bullied a classmate for two weeks because I thought she was doing the same kind of thing, that she deserved it. And the people who are sending me death threats, they think they’re doing “good,” that they’re doing it for the right reasons, just like AfD voters when they put their marks on the ballot paper.

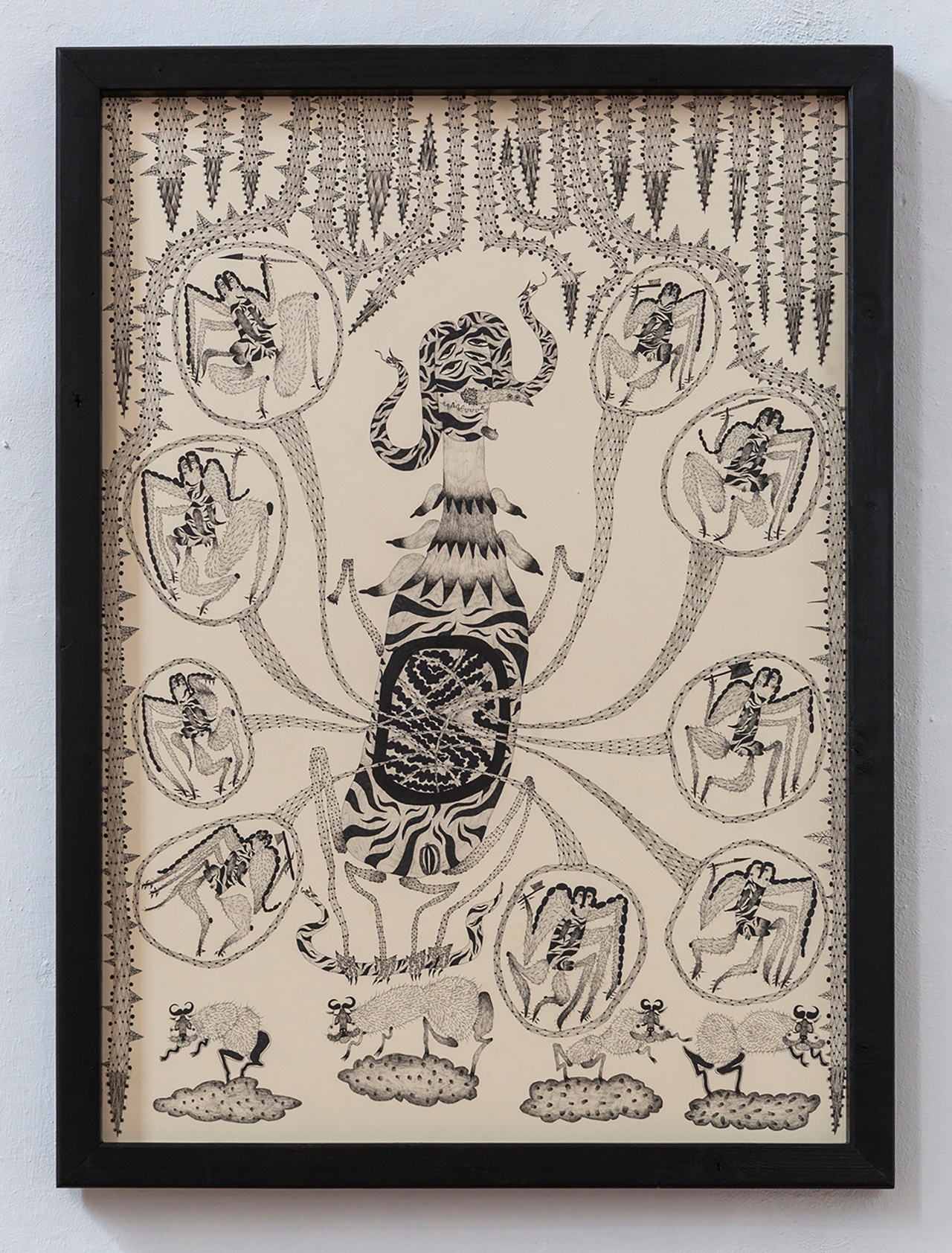

Sophia Süßmilch, “Ich habe einen guten Charakter, ich habe nie Menschenfleisch gegessen,” 2024

KÖLBL: But despite the abyss of the internet, social media also provides the potential for creating networks. Have you experienced any solidarity there? Or in analog space?

SÜSSMILCH: I got to enjoy the Streisand effect: the CDU wanted to prevent the exhibition, which ended up drawing a lot of attention to the show and to me. People wrote nuanced, affectionate things to me. I have experienced a lot of solidarity and humor, which has been really moving. Every person who writes “keep on going” to me helps me. As does the solidarity in person, the support of my partner and my colleagues. The reactions of audiences were amazing, too. We had very little time for preparation – three months for the exhibition and three rehearsal days for the performance – but we were really happy with things in the end. For that, we’re thankful most of all to the amazing team at the Kunsthalle and especially Anna Holms – my show was the first that she’d curated. A lot of people who saw the performance – a good number of older men among them – cried by the end. Then the next day, two older female visitors got super into the S.C.U.M. Manifesto (1967) by Valerie Solanas, which was one of the exhibits in the show.

KÖLBL: You deal with cannibalism in your art in a much more complex way than fairy tales do. Moral categories lose their stability in the process. You propose the incorporation of one’s own child into one’s own body as a feminist gesture, one that undermines the traditional patriarchal image of motherhood. What are you aiming for with this?

SÜSSMILCH: I’m offering up a revenge narrative: childbearers take their revenge on the world. The fact that it would be within their power to end humanity by refusing to perform reproductive labor seems, for many, difficult to bear. The same’s true for the fact that motherhood isn’t just about love but also about a huge amount of overload. There’s cases where women give birth to children then kill them right after, as they don’t know what else to do with them. Then they bury the bodies in plant pots on their balcony, so that the child is still close by. Motherhood is characterized by ambivalent behavior and feeling – rarely to such an extent, of course – and overload is also a major part of it. That’s why I find it super problematic to hold up mothers as saints. I certainly don’t want to dismiss motherly love; it’s just that I feel it’s important not to leave mothers alone in their difficult moments. There’s far too little attention paid to the negative, conflictual aspects. For my preparations I spent a lot of time thinking about Munchausen syndrome by proxy, a psychological condition that most often affects mothers and their kids; the mothers hurt or poison their children, as a means of putting themselves center stage, of becoming the center of attention. The kids often end up dying. Reading autobiographical accounts on the topic, I found myself thinking whether society might not partly be to blame here. If the social environment or the law force pregnant people to carry children to term against their will, who’s to blame for the overload that, in the worst-case scenario, ends up harming the child? In the cannibal, I see a figure protecting themselves from social pressure and responsibility.

KÖLBL: The psychoanalyst Anita von Raffay sees a similar figure in Medea, a character from Greek mythology known as a child murderer: “In her deed, Medea abandons the tradition that motherhood and children are a woman’s raison d’être, that a woman with children must renounce sexuality and passion.” [12] Raffay also regards Medea as an avenger in a society that denied her equal rights as a woman. [13] Does the incorporation of the child into the cannibal’s own body perhaps not only serve to symbolically protect the child but also offer a mode of self-preservation in an environment hostile to mother figures?

SÜSSMILCH: The image of the “good mother” is still one of self-sacrifice, of renouncing your own needs. That’s why I wouldn’t take the statement “Oh, you would be such a good mother” as a compliment. I think care work is amazing, of course. But it can take place somewhere other than within a nuclear family; it can be practiced in many ways. I also looked into psychoanalytical interpretations of the antagonistic figure of the stepmother. In fairy tales, she always represents the evil aspects of the mother, split off. With Gretel and Hansel, the witch takes on that function: she’s framed as the evil part of the mother, the part that wants to eat the children. The literary scholar Michael Maar has read this against the historical backdrop of the Thirty Years’ War and the famines it brought with it. [14]

“Sophia Süßmilch: Then I’ll huff and I’ll puff and I’ll blow your house in,” Kunsthalle Osnabrück, 2024

KÖLBL: Both the figure of the witch, like in Gretel and Hansel, and of the cannibal are devalued as Others by cultural history. And it’s these Others that you, together with your performers, are now embodying in a kind of feminist project of appropriation. As a white female artist, how do you deal with the fact that the figure of the cannibal has historically been particularly marked not only by sexism but also by racism?

SÜSSMILCH: I was mostly concerned with contemporary cases, including the one of Armin Meiwes, known as the Cannibal of Rothenburg, and Bernd Jürgen Brandes. The book Sexueller Kannibalismus: Sexualwissenschaftliche Analyse der Anthropophagie (2007) by Klaus Beier was also important to me, even if his arguments are very Catholic. The author’s view is that if people were more religious and there were more ritual cannibalism in the church, the problem would be less severe – at least that’s how I understood his line of thought. Someone should tell that to the CDU; they’d probably be delighted to hear it. Of course, I’m aware that many written and visual depictions of cannibalism are characterized by racism. Across human history, cannibalism appears with various reasons, but still, it’s often about othering. There’s the antisemitic blood libel, which accuses Jews of being child murderers who drink the blood of their victims. As a white, cis woman with a family history of Nazism, I deal with this cultural history by usurping all of this evilness and saying, “It’s me, your wife, who eats your kids.” This includes birthing people all over the world – it’s not the “evil warrior” or the “evil bogeyman” who comes from the outside. The idea is one of a worldwide movement, in which all people capable of birthing children join together and call out: “No more!” Obviously, there’s also something misanthropic and fascistic about such a birthing strike.

KÖLBL: Still, the poem you used as a reference point with the press, “Silvester bei den Kannibalen” (New year with the cannibals, 1931) by Joachim Ringelnatz, makes ample use of racist clichés. Is it possible to create productive readings of that kind of material?

SÜSSMILCH: It’s certainly true that it contains racist stereotypes. But at the same time, I wonder whether the poem doesn’t present a certain break in its last line: “with melancholy, and then begin to weep.” And isn’t Ringelnatz also ridiculing racist clichés? The way I read those lines, he isn’t about earnestly repeating a racist narrative but about distancing himself from one. Right at the very end of the poem especially, I was reminded of the case of Armin Meiwes. For people who give in to their cannibalistic paraphilia and eat parts of another person, the desire to eat someone in order to never be abandoned often develops in childhood, before sexual neurosis sets in – the sexual excitement only comes later, grafted onto the damaged self and the associated image of relationships with others. I feel there’s a similarity with the poem here in the inner turmoil between killing and remorse. Someone does a terrible deed, entirely conscious of it, then regrets it. Killing, in its actuality, is an uncomfortable act, but one that’s required to incorporate others into one’s own body: I could just eat you right up.

KÖLBL: You suggested in your publication ABC der klugen Entscheidungen (The ABC’s of clever decisions, 2023) that cannibalism might potentially have something to do with love. Under the entry for L, you write: “Cannibalism or eating bogeys / If you feel the wild urges within you, decide here with a dash of LOVE.” In the same book, Jasper Nicolaisen writes of you, “As you can see online, she works a lot with nudity. Yawn! That’s just what So-and-so did a hundred years ago.” [15] The impulse being ironically discussed here is one I know myself – in my case, though, it’s because I’m tired of artists’ naked bodies being objectified, time and time again. Why do you find it’s something still worth sticking with?

Eugène Delacroix, “Medée furieuse,” 1838

SÜSSMILCH: Being naked is simply the most plausible thing to me. At the moment it would seem more plausible to put something on, I’d do so. I don’t even register nudity anymore. Like in Florentina Holzinger’s plays, for example, I don’t even notice that the performers are naked. But I see it really clearly as soon as they hold an apple. It’s the exact same way that the performers’ hats and guinea-pig masks in “Then I’ll huff and I’ll puff and I’ll blow your house in” develop their expressiveness. If you can’t see past the nudity, though, you actually can’t see anything at all. Naked bodies aren’t just expressive, they’re also hilarious.

KÖLBL: I had a similar experience watching the recording of the performance. But in the context of public space, which is where the performance took place, there’s always the danger of bodies being sexualized.

SÜSSMILCH: That’s why I’m so into performing alongside my mother. She’s just there, like a nuclear power station of calm. You can see that she’s given birth to five children and never wore a bra in her life. She doesn’t care if some man looks and says something. And that transfers over to me when I’m stood next to her, and then I don’t care whether I like my body or not. Shame is an instrument of power – and I’m not going to be ashamed. Take your magnifying glass and look right at me. It’s just a body. I’m free and you can watch me in my freedom. The more often I do it, the freer I feel; the more you see of me, the more invulnerable I become. There’s still some vulnerability, though: my weight often fluctuates and people can recognize my struggle with the female body. But when everything’s put out there, there’s not much shame anymore – and a lot of strength. It’s a feminist gesture of empowerment, which actually wasn’t my initial intention at all. At the start, I always said that it’s not for political reasons that I get undressed; it’s just that I like being naked. I wanted to avoid that whole discussion. Myself, I don’t see the body in such a sexualized way, and I often find it too much stress to get dressed. And would this performance have been better if we’d have had some weird clothes on? Yeah, I don’t think so. This cheeky movement of body parts, when you see asses – that’s amazing. With the few props we had, we managed create hybrid beings. People in the audience can sexualize it still though, obviously. And if someone does something creepy, I’m always ready stop the performance in its tracks and to throw the visitors out.

KÖLBL: Female-coded bodies remain highly political – even in their artistic manifestations. Back at the start of July, Esther Strauß’s sculpture Crowning (2024), of a birthing Virgin Mary, was beheaded. And on the campus of the University of Houston, Shahzia Sikander’s sculpture Witness (2023) was also decapitated. [16] Was nudity one of the factors that played into the outrage over your exhibition?

SÜSSMILCH: Naked bodies of FLINTA [17] people create all kinds of frenzied fear in people. I’m glad that I’m now allowed to go topless at Berlin’s open-air pools, just like men are. When I said to Der Spiegel that “breasts are a secondary sexual characteristic, just like men’s beards. Why should I actually have to cover my breasts in public when men don’t have to cover their beards?” they framed it as a joke. [18] But I was dead serious. Micol Hebron’s Instagram project Male Nipple Pasty has demonstrated the absurdity of how naked breasts are perceived. She places images of male nipples over the breasts of other bodies, so that the images don’t get deleted. Over the years, I’ve noticed reactions to my naked body changing: the more conservative the backlash is, the more that female bodies are sexualized. It’s something I’m particularly exposed to on social media, where I’m accused of being an “attention whore.” But I just see a naked body as a blank canvas. Everyone has one, too – so there’s an enormous potential for relatability.

“Sophia Süßmilch: Then I’ll huff and I’ll puff and I’ll blow your house in,” Kunsthalle Osnabrück, 2024

KÖLBL: Your art also plays a lot with the subversion of expectations. For the “Sanatorium Süßmilch” at Francisco Carolinum Linz, for example, you turned yourself into an exhibit – for the duration of the exhibition, 30 days, you lived in the museum – while at the same time massively reducing your availability as an exhibit by only making the show publicly accessible for two hours a day. In 2020, you invited colleagues to slander you as an artist and your work as part of Denkmal der Beleidigung (Memorial to insult). [19] There were commemorative marble plaques bearing various bits of text; “last descendant of cheap provocation,” read one of them. Do you feel that there’s still potential in provocation? I’m asking, first of all, because I have the impression we’re living in a moment where it’s difficult to engage in productive conflict within the cultural sector; even if it arises, it quickly derails. Second, we’re seeing more cases like the reaction to your exhibition – where art is reduced to outrage as a means of fighting battles that have little to do with the art itself.

SÜSSMILCH: For me, my art is about communication, not provocation. If someone feels provoked by a naked body – sorry, that’s not my fault. This all revolves around ambivalences that I explore through narrations. When people genuinely feel provoked, I’m happy to speak with them about it. But with Marius Keite, I didn’t offer to talk; I challenged him to a rap battle instead. Because in the end, his worldview and mine clash too much: the CDU are about “protecting life” and criminalizing abortion; I believe in bodily self-determination. There’s nothing these politicians are more concerned about than preserving their own power – and to do so, they’re happy to dip their toes in the Far Right. Even if it’s become very difficult to remain in dialogue, I’d still be happy to do an artist talk in Osnabrück. But I’ve no idea what rapprochement might look like. Maybe, instead of a rap battle, we could just sing karaoke to each other to show our own humanity. No insults, just songs.

KÖLBL: What would you sing?

SÜSSMILCH: “Es war einmal ein Fisch mit Namen Fasch,” something by the Beatles, then “Bloody Mother Fucking Asshole” by Martha Wainwright, obviously.

Translation: Matthew James Scown

Sophia Süßmilch was born in Munich in 1983 and is a Bavarian Berliner with Austrian life experience. She is a visual artist, performer, and author. She works in multimedia and across genres. Currently, she is writing her debut novel Die Kannibalin and is developing feminist networking projects explicitly orientated toward non-suffering in a collective.

Antonia Kölblis an art historian and editor-in-chief at TEXTE ZUR KUNST.

Image credits: 1.+3.+4.+5.+7. Courtesy of Sophia Süßmilch and Kunsthalle Osnabrück, Photos Lucie Marsmann; 2. Public domain; 6. Public domain

Notes

| [1] | Stefan Lüddemann, “Groteske Fantasien und Kannibalismus: ‘Kindern nicht zuzumuten’: Kunsthallen-Ausstellung startet mit Trigger-Warnung,” Neue Osnabrücker Zeitung, June 14, 2024. |

| [2] | “CDU Osnabrück distanziert sich von Kunsthallen-Ausstellung ‘Kinder, hört mal alle her’ und ruft zum Boykott auf,” press release by CDU faction of the City Council of Osnabrück, June 15, 2024. |

| [3] | Report by the Lower Saxony branch of the German Press Agency, published inter alia as “Kunsthalle Osnabrück: CDU ruft zum Ausstellungsboykott auf,” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung; “Cancel Culture: CDU ruft zum Boykott einer Ausstellung der Kunsthalle Osnabrück auf,” Monopol; “‘Kannibalistische Fantasien propagiert’: CDU fordert Schließung von Kunstausstellung in Osnabrück,” Der Spiegel; “Kunsthalle Osnabrück: CDU ruft zum Boykott einer Ausstellung auf,” Die Zeit; all June 15, 2024. |

| [4] | See CDU press release from June 15, 2024. |

| [5] | Harff-Peter Schönherr, “Oberbürgermeisterin gegen den Rat: Kunsthalle Osnabrück bedroht,” Die Tageszeitung, April 3, 2022. Another press release from the CDU’s Osnabrück City Council faction followed on June 27, 2024 (“CDU: Kunsthalle muss sich weiterentwickeln und professioneller werden: Konstruktiver Dialog mit der Leitung der Kunsthalle lässt CDU auf Konzeptoptimierung hoffen”), rejecting this accusation. |

| [6] | Willkommen Österreich, episode 607, April 16, 2024, from 00:10:20. |

| [7] | Nina Schedlmayer, “Oh Schreck, nackte Frauen und schiache Wörter!,” Artemesia: Kunst und Feminismus, June 21, 2024. |

| [8] | See CDU press release from June 15, 2024. In the June 27, 2024, press release, Kämmerling contests the accusation that she called into question the freedom of art. |

| [9] | Pauline Jäckels with Marten Brehmer, “‘Oyoun’: Fördermittelaffäre in Joe Chialos Kultursenat,” Neues Deutschland, July 5, 2024; Sonja Zekri, “Berliner Kulturzentrum Oyoun: ‘Zulasten der Meinungsfreiheit,’” Süddeutsche Zeitung, July 21, 2024. The case is still being fought out in court; see: “Fördermittel: Kulturzentrum Oyoun erzielt juristischen Erfolg gegen Chialo,” Süddeutsche Zeitung, July 22, 2024. |

| [10] | John Goetz and Manuel Biallas, “Als Reaktion auf Kritik: Bildungsministerium wollte Fördermittel streichen,” NDR Panorama, June 11, 2024; see also Transcript of the internal mail traffic at the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) for an upload of related documents. |

| [11] | Jean-Philipp Baeck, “Neonazis feiern Sonnenwende: Hitlerjugend reloaded,” Die Tageszeitung, June 21, 2024. |

| [12] | I thank Reinhard Lindner for bringing this to my attention. Antia von Raffay, “Medea – Die Dunkle – Die mit dem guten Rat,” in Abschied vom Helden: Das Ende einer Faszination (Freiburg im Breisgau: Olden, 1990), 166–82, at 172. This and all other quotations translated by Matthew James Scown. |

| [13] | Ibid., 182. |

| [14] | Matthias Hanselmann, “Verarbeitung von ‘grauenhaften Menschheitserfahrungen,’” interview with Michael Maar, Deutschlandfunk, December 20, 2024. |

| [15] | Jasper Nicolaisen, “Finissage Nachdenkschwert, Süßmilch: Ein Soloabenteuer um schlechte Entscheidungen,” in *Sophia Süßmilch: Das ABC der klugen Entscheidungen* (Nuremberg: Institut für moderne Kunst, 2023), n.p. |

| [16] | See Michael Wurmitzer, “Künstlerin zu geköpfter Maria: ‘Ausdruck patriarchaler Gewaltbereitschaft,’” interview with Esther Strauß, Der Standard, July 4, 2024; Rhea Nayyar, “Sculpture of Virgin Mary in Labor Beheaded in Austrian Cathedral,” Hyperallergic, July 7, 2024; and Rhea Nayyar, “Shahzia Sikander Says No to Repairing Her Beheaded Sculpture,” Hyperallergic, July 11, 2024. |

| [17] | Translator’s note: FLINTA is an acronym in German for women, lesbians, intergender, non-binary, trans, and agender people (Frauen, Lesben, Intergeschlechtliche, nichtbinäre, trans und agender Personen). |

| [18] | Ulrike Knöfel, “Streit über kannibalistische Fantasien: Kann man Kinder auch humorvoll verspeisen?,” Der Spiegel, June 18, 2024. |

| [19] | See insert in Gerhard Müller-Rischart, Magnus Müller-Rischart, and Katharina Keller, eds., JAJA – NEINNEIN – VIELLEICHT, exh. cat. (Munich: Hubert Kretschmer, 2020). |