LECTURE AS LABORATORY A Conversation between Armin Chodzinski and Sibylle Peters

Sibylle Peters, "Touching You," Kampnagel, Hamburg, 2024

SIBYLLE PETERS: Lectures and lecture performances are topics that have connected us both for over two decades, so I’m excited to talk to you about them. They connect us because we have similar approaches: we understand the lecture not only as the conveying or declaring of something that’s already known but also as a test setup, as an experiment, as research. We’ve arrived at a point where a huge variety of talk formats are practiced: from instruction to motivational speeches, from the humanities lecture to sales presentations. Switching between these forms facilitates a virtuosity that I really appreciate in your work. Which term – lecture or lecture performance – do you use to describe your practice?

ARMIN CHODZINSKI: I stick to lecture and often fight back against lecture performance. For me, a lecture is a space that is built together with the audience and that still follows clear language conventions, which I take seriously. If I use lecture performance, that influences the reception, which is determined by prior notions and the audience’s broader set of expectations. So, the audience then tends to focus more on the performative and sees much of what happens as a performative illustration. It’s better when the audience expects a lecture and then sees what comes next.

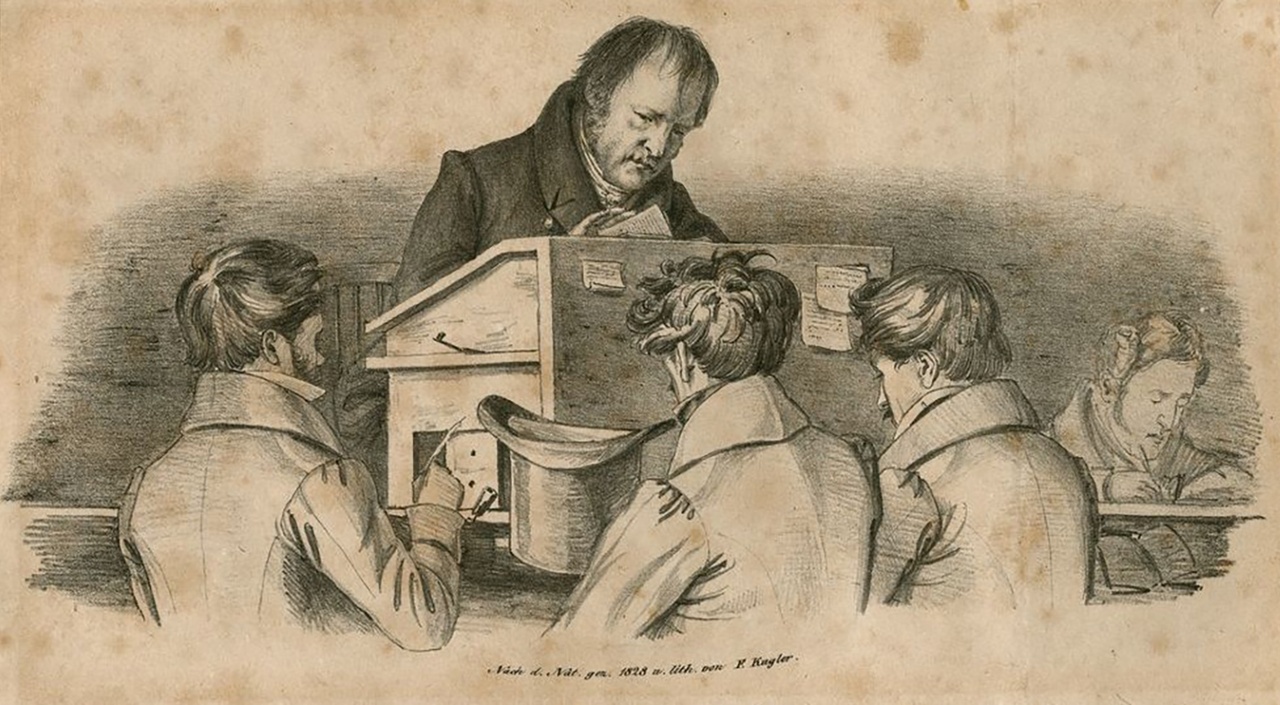

PETERS: The label lecture performance is kind of like calling water wet – because the German word for lecture, Vortrag, already has a performative element within it. Which is how the word used to be meant, in a question like, Does the person have Vortrag? – meaning, is that person’s performance good? Or, What’s the violin player’s Vortrag like? So, what’s unique about her playing style? Historically, the most recent transformation in the meaning of the word took place around 1800, and since then lecture has been used in the modern sense. The technical development of the printing press made it so that almost all students could afford textbooks, which made the classic lecture – where the lecturer reads something aloud and the student takes notes – superfluous. This resulted in a crisis of the academic lecture, which led to reflections on how the format could be refashioned, specifically in a more performative way: no longer as something to be read but as something to be presented. This is the context in which Wilhelm von Humboldt advocated bringing research and teaching together and promoted freely worded presentations, which he believed would benefit students, but also teachers, who would arrive at new insights through this practice. For him, it was about a productive, knowledge-poietic [wissenspoietisches] speaking. Johann Gottlieb Fichte, for example, used a freely delivered style of presenting in the development of his philosophy at the newly founded Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, as did Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, who in the twilight of his career had age-related difficulties finishing sentences. So, his students did it for him: they completed his sentences in the notes they took.

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel with students

CHODZINSKI: Performance, in particular, is key to the production of evidentness in lectures. That’s something I learned at an early stage – when I did a presentation at school, without having the least bit of knowledge about the subject. I was holding in my hands these two monumental books that I hadn’t read. I used them to physically work the room, with huge, earnest gestures and a clear, assertive language, despite knowing as little about the subject as I knew about the man in the moon – or, in this case, about the history of witches. And afterward, I was praised beyond words, even by my teachers, who should have known that it was all made up. My physicality definitely played a part, but my total conviction did too, the urgency of my speech, with a working-class kid’s feeling of pugnacious inferiority. This moment was a shock. I realized, all of a sudden, how important presence is, how much presenting has to do with taking and offering space. I relished occupying the space, but despite that I still experienced a painful failure: the substance was blurred, obfuscated, etherealized, missing, and seemingly irrelevant. Today, I’d say that this presentation was the starting point. Since then, I’ve often worked with lectures. My initial reaction back then was different: I decided to completely avoid such situations and to stop speaking in front of audiences. It was only after I started studying art and hearing and seeing a lot of lectures that I slowly reconciled myself with public speaking and understood it as a complex form.

PETERS: Even ancient rhetoric described evidentness as a rhetorical figure in which what is being spoken about is made present in the moment of speech and in the body of the speaker. When orators are visibly moved by a topic, when they fight back tears or something, it seems particularly authentic and impressive. But it brings with it the risk of losing self-control. In the most extreme case, the oration passes over into crying; the referentiality breaks down. Lecture-performance artists often seek out this moment of making-present and are prepared to take the associated risks.

CHODZINSKI: The question is, What form of evidentness does this lead to? Does an evidentness emerge that you can build on? Where does this evidentness appear? And how can you get away from the sentimentality of the show element? This is what I expect from lectures: making it clear at what point something really emerges, the point at which, together in this space, something seems to appear, something that I maybe still can’t formulate, that lies beyond the pronouncement.

PETERS: Early on in my critical encounter with lectures, I still thought: self-evidence, yes, that’s exactly what it’s about! We invent new forms of knowledge for which, so to speak, the lecture is the laboratory, where we always seek to make what we say directly self-evident: performative evidentness. My first lecture performance, for instance, was about forgery – and in its own way, was a forgery itself. It was called Laboratory of Fake (2001) and about fakes as a practice of knowledge production. Like, what do you need to know in order to make a good fake? I recorded the lecture in advance, with all the little mistakes and interludes, then performed it live – which I tried to perfect so that people wouldn’t realize immediately, only afterward. This turned the work into an illustrative, demonstrative, but also deconstructive game with what I was saying about forgery. It’s a game that unfurled in the space between referentiality, performance, and evidentness. I was really inspired by the first lecture performances that I had encountered, especially John Cage’s Lecture on Nothing (1961), which is, of course, also a self-exemplification. In my own lecture performances, I still work with a form of self-exemplification in that I look to correlate the content that is presented with what happens during the performance. In Touching You (2024), for example, I was recently with 9 other people in a kind of “cuddle puddle,” where various kinds of touching took place. And that’s the situation in which I then gave a lecture on touching. It was almost impossible not to lose my thread whenever the quality of the touching suddenly changed. After my engagement over the years with work by you and other colleagues, and with theoretical studies, too, it became clear to me that this perfect figure of self-evidence doesn’t exist, because it sort of collapses into itself at a particular point … which is actually a good thing. This position of power that you just located in oration – so, that the person orating is in the position of the one with knowledge and, as soon as that is performed well, everything they say is transformed into knowledge – this sovereign position is always put at risk to some extent in the course of self-exemplification.

Sibylle Peters, “Touching You,” Kampnagel, Hamburg, 2024

CHODZINSKI: Competence and power are performed and thus can also be developed into a strategy. One such performance of competence would, for example, be if a company’s accounting department had a problem because of inconsistencies in the financial analyses. In the past, convincingly performing competence in accounting would have been possible by presenting an Excel spreadsheet with tiny fonts and by speaking very quietly. A tactic that makes use of a cliché, because if the assertion of power stands for competence, then the opposite is true for mathematical, scholarly, or nerdy matters, where specialist competence is the polar opposite of social competence. A different context, different requirements, a different performance, but it’s always about questions of power: with the presented material, the voice, the posture, the demeanor, a story is told. It really doesn’t have to be a deliberate strategy; it can also work without one.

PETERS: You seem to advocate the position that a lecture performance should, specifically through its performance, take a critical stance toward lecture formats that safeguard power. In these kinds of power-safeguarding formats, the position of the lecturer as the one who knows is further reinforced. In a traditional lecture, the surplus value that emerges between saying and showing is normally ascribed to the lecturer – in your example, that’s the person from accounting. The lecturers accumulate this surplus value, so to speak; it becomes their capital. For you as a performer, what role does capitalization play on a material level?

CHODZINSKI: I come from the visual arts, and my practice was usually immaterial, which often enough means: for nothing! But with lectures, I was able to earn a living. Back then, a lecture in the art context – whether held by an artist or otherwise – didn’t have a price attached to it, but the same speech offered as a performance in a cultural, economic, or institutional context was self-evidently entitled to a fee. What interested me most of all was how to talk about topics like economics, urban development, art, and pop culture without falling into making declarations.

PETERS: In my research on historical and contemporary forms of the lecture, I found the intersection with economics particularly thought-provoking, especially in the context of the wider discussion on the commercialization of knowledge. In the 2000s, before the financial crisis, there was an era of management consultancies that, for the most part, sold “presentations.” In that context, the terminology underwent another change – so today, people speak more about presentations than about lectures. Lecture performances, on the other hand, often try to counter capitalist logics to some degree, like by collectivizing the surplus that emerges between showing and saying. Whereas in a power-safeguarding lecture scenario, the surplus is assigned to the speaker, the thing that emerges in lecture performances is often experienced situationally as a collective insight.

Armin Chodzinski and the #drccallstars, “F wie Feierabend, oder: Wer repariert die 5-Uhr Sirene?,” Feierabendhaus Ludwigshafen, 2023

CHODZINSKI: These kinds of collectively produced insights can also be generated by multivocality, which is something that is central in my work, too. F wie Feierabend, oder: Wer repariert die 5 Uhr Sirene? (F as in Feierabend [roughly, the evening after the work day is over], or: Who repairs the 5 o’clock sirens?, 2022), for example, was a lecture performance that came as a stage show with a large ensemble: three actors, two sidekicks, three musicians, and me as the person giving the lecture. This setup led to the audience having a clear expectation: There’s a performance! Which is why I’m very consciously using the term lecture performance here. That evening reflected on the idea of Feierabend in the political and social sense. It took place in a Feierabendhaus [a dedicated building, usually in an industrial factory, offering leisure, cultural, or educational activities to workers], and a central part of it was to shed light on this historical context, because for a lot of the audience, it really was just a big concert hall. I myself appeared as an author and lecturer, as a particular talk-giving figure who was constantly deconstructed by the other participants on the stage. I had about 15 percent of the speaking time and spent most of that either yelling or staying quiet, on a tall scaffold in the middle of the space, without a microphone. The show linked various knowledge resources into a format that was more on the theatrical side, calling on various spatial structures and forms of performing, like dance halls, churches, and concert stages, or performances and choirs. The multivocality that emerged from this brought out various perspectives and positions. There were no clear lines of argument; rather, everything was dialectically deconstructed straight away by other points of view, whether via the body, via clothing, via actions in the space, or via the positions themselves. It was about creating a space together – with the other participants and especially with the audience – that questioned the positions of power held by the speaker and the space, that showed them, stylized them, and at the same time dissolved them.

PETERS: Maybe you could say: The lecture is a format that always speaks from within a discourse, from a position of power. But it’s also a format that can be hijacked by people who then use the process of the lecture to put themselves in a position in which they can, for the first time, speak and be heard. Lecture performance as the possibility of self-empowerment – of contributing to discourses in which, for various reasons, you normally would not get to speak.

CHODZINSKI: I don’t come from an intellectual home, so I always felt like the underdog among people who grew up in educated, well-off situations. Which is maybe why the spaces in which lectures happen were, for me, also always performance spaces, arenas. They gave me a territory, a space in which I was not under any circumstances prepared to hide, so – showtime!

PETERS: There’s a tradition of people from marginalized positions appearing in these arenas: In many 19th-century societies, women were banned from even speaking in public. Around 1860, many women in the United States used the practice of giving free, inspirited lectures, so that they could be heard regardless. Like Achsa White Sprague, the trance lecturer: she gave philosophical lectures against enslavement, but while speaking she went into a kind of trance, professing that a (male or even divine) spirit was speaking through her. A whole series of women in the United States conquered the lectern as trance lecturers.

Achsa Sprague

CHODZINSKI: In 19th-century painting, there were female artists, like Hélène Smith, who claimed that they painted in a trance. White Sprague’s and Smith’s bodies functioned as mediums and made it possible for them to attain visibility as speakers and artists, but we read of Pythagoras that he concealed his own physicality. He taught his students from behind a curtain, the idea being that the Logos would be distracted by his own outward appearance, his physicality, and by visually observing him. I find that really remarkable: performativity, so, the body positioning itself relationally in opened-up space, affects the concentration and creates a particular form of cognition.

PETERS: We’ve since found many new strategies, like collective strategies, for undermining the potential concentrations of power in the lecture. How can we arrange collective constellations for lectures, so that more people can occupy the position of the one with knowledge?

CHODZINSKI: Collective strategies work at various levels and highlight once more how the lecture has a number of formal structures that, in practice, can be questioned or molded. For example, lectures have time limits. In some contexts, I try to forestall the end. In other words, the lecture breaks down into a situation of everyone talking and becomes a joint thinking, speaking, and acting – the marking of an end, the moment of before and after, is avoided. For instance, by technically maintaining the structures while also introducing other forms that work against them. One example of this would be my opening speech for Simon Kindle’s 2024 exhibition at Kunstmuseum Luzern. I chose the strategy of the individual speaker. As always, I wore a suit, and for the beginning of the lecture, I put on a tie. The lecture was guided by a gymnastics exercise played from an LP from the ’70s. Together with the audience, I followed the invisible voice and performed the exercise routines, which fundamentally changed the relationship between the public and me as the speaker. So, all of us began the event – which had been announced as a lecture – with a bodily experience. There was a direct break with the usual form. As the lecture proceeded, I read a text about Michel Foucault’s heterotopias, concentrating on his idea of the back as a place where utopian thought originates. Then, in front of his works, Simon Kindle performed the gymnastics exercises following my instructions, and the audience was able to observe and assess how well he did them. The lecture, bit by bit, became a performance that was not just about conveying content; it was also about experiencing and feeling in space, about recognizing and sensing. My role as speaker changed constantly – at the end, I gave up control completely.

Hélène Smith, “Paysage extraterrestre,” 1896

PETERS: For me, that’s embedded in a context that I refer to as “research of all [people].” Germany’s constitution guarantees the right to education, so, in a way, the right to attend a lecture. But we don’t have a right to research. Research is a privilege. It’s important to question that, to turn it around by demanding a right to research. Which is why many of my art projects are collective research processes, involving heterogeneous groups. Participants share their experiences and findings with one another and then present them to a wider public, once again bringing into question what has been unveiled. Ideally, the research continues into the actual lecture situation itself.

CHODZINSKI: Gradually, I began concentrating on the question of what adjustments you can make to shape a space. My focus was on the question of how to open spaces up, without constructing an overbearing hierarchy of knowledge while doing so – something that I’d previously tried to do with collective approaches. In one of those projects, there were eight tables, each with five to six people sat at them, and one of their tasks was to cut vegetables for a potato soup being cooked in the middle of the room. In addition to that, each table had a script with various parts of it marked up, and spotlights pointed toward the tables were used to conduct which group had to read from printed research reports on universal basic income. So, a collective presenting that, through the dialogic text, turned into a sit-down conversation at the table. But the stage direction remained in one person’s hands, because I was the one who defined the rhythm of which table should read from the report; I was the one who marked the text, who’d done the research work, and who had it read aloud in this form, in the hope that the lecture would expand, change, and develop in conversations. The substance of it was rather laborious, but poetically it worked super well – and was also confusing, because it was never clear who was in which role, or who could be what.The question was always, How can you collectivize the lecture and also ensure that it lasts and that it continues developing in its substance? The goal is to show the construction of the speech act and to integrate the audience into a collaborative production. This also means orchestrating the audience’s speech, because as soon as someone’s own voice has, for whatever reason, taken up the space, there’s a high chance that it will take up space again of its own accord.

Armin Chodzinski and the #drccallstars, “F wie Feierabend, oder: Wer repariert die 5-Uhr Sirene?,” Feierabendhaus Ludwigshafen, 2023

Translation: Matthew James Scown

Armin Chodzinski studied fine arts, worked commercially, and did his PhD in anthropogeography. He qualifies losses, desires, and hopes, among others, through lectures, performances, exhibitions, drawings, texts, and videos in different contexts, including exhibition spaces, theaters, academic symposiums, and businesses.

Sibylle Peters wrote the book Der Vortrag als Performance (transcript, 2011) and forsook humanities for the theater. There she has, among other things, developed the so-called “Forschungstheater,” in which children, artists, and scientists encounter each other as researchers. She is currently working on a project about New York’s Swinish Multitude and on a Theater of Touch.

Image credit: 1. Photo Cylix; 2. Public domain; 3. + 7. Marcus Schwetasch; 4. Photo Alexandra Polina; 5. + 6. Public domain