Though not devoid of artistic and historical provocations, exhibitions of Andy Warhol’s work had, for a long time, dispensed with sexually explicit imagery. Now, at Neue Nationalgalerie, portrayals of men and their penises exemplify the more overtly gay aspects of Warhol’s output, while at two other venues, the artist’s sexuality serves as backdrop: for focusing on his friendship with Keith Haring, at Museum Brandhorst, and for examining his later life, at Fotografiska. Independent of its curatorial framing, Warhol’s work on view both subtly and skillfully shifts viewers’ attention from a straight to a queer reading, as Barbara Reisinger argues in her comparative review of the three shows.

Twenty-two years ago, the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) in Los Angeles mounted what they proclaimed to be a comprehensive exhibition of Andy Warhol’s work, yet it excluded anything visibly sexual. It was the last stop of a retrospective first organized by the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin. Back then at MOCA, Jennifer Doyle, who had published about the queerness of Warhol’s art and happened to get into the press preview, sought refuge from the thoroughly “de-gayed” experience in her neighborhood gay bar that, notably, had an original print from Warhol’s Sex Parts series (1978) decorating its back wall. Fortunately, times do change. In 2024, the first Warhol exhibition at the Neue Nationalgalerie since that show has placed his most sexually explicit series of screen prints, showcasing men having sex with men, in the center of its venerated exhibition hall, within walking distance of the Motzstraße gay scene.

The arrival of Warhol’s colorful images of crotches and butts within the halls of fine art feels celebratory and necessary, but also quite belated. If the historical conditions of his lifetime did not permit the artist to live and make art as an openly gay man, gayness and queerness nevertheless pervade his oeuvre, from 1950s drawings of beautiful young men and their penises right up to the homosocial scenes of the Last Supper series (1984–86) and the full-body portraits of Jean-Michel Basquiat in a jock strap posing as Michelangelo’s David (1984). As the Nationalgalerie’s “Andy Warhol: Velvet Rage and Beauty” makes exceedingly clear, at last: a “de-gayed” version of Warhol is not a comprehensive perspective on his work.

For the two other Warhol exhibitions more or less concurrently on view, at Museum Brandhorst, Munich, and Fotografiska, Berlin, the artist’s queerness is more of a premise than a point to be made. “Andy Warhol & Keith Haring: Party of Life,” in Munich, centers on the friendship of two gay artists of different generations, and works images of naked men and gay sex into the fabric of the exhibition. Fotografiska’s “Andy Warhol: After the Party” takes up the narrative of Warhol’s later life and is based on the Netflix series The Andy Warhol Diaries (Andrew Rossi, 2022), which recasts the artist’s sexuality through personal narrative – his romantic relationships with younger, handsome men and his obsession with the perceived flaws of his own body. The small show thus aligns with the Netflix vision of a vaguely melancholic “man behind the myth” who was driven by a perpetual search for authentic intimacy and belonging.

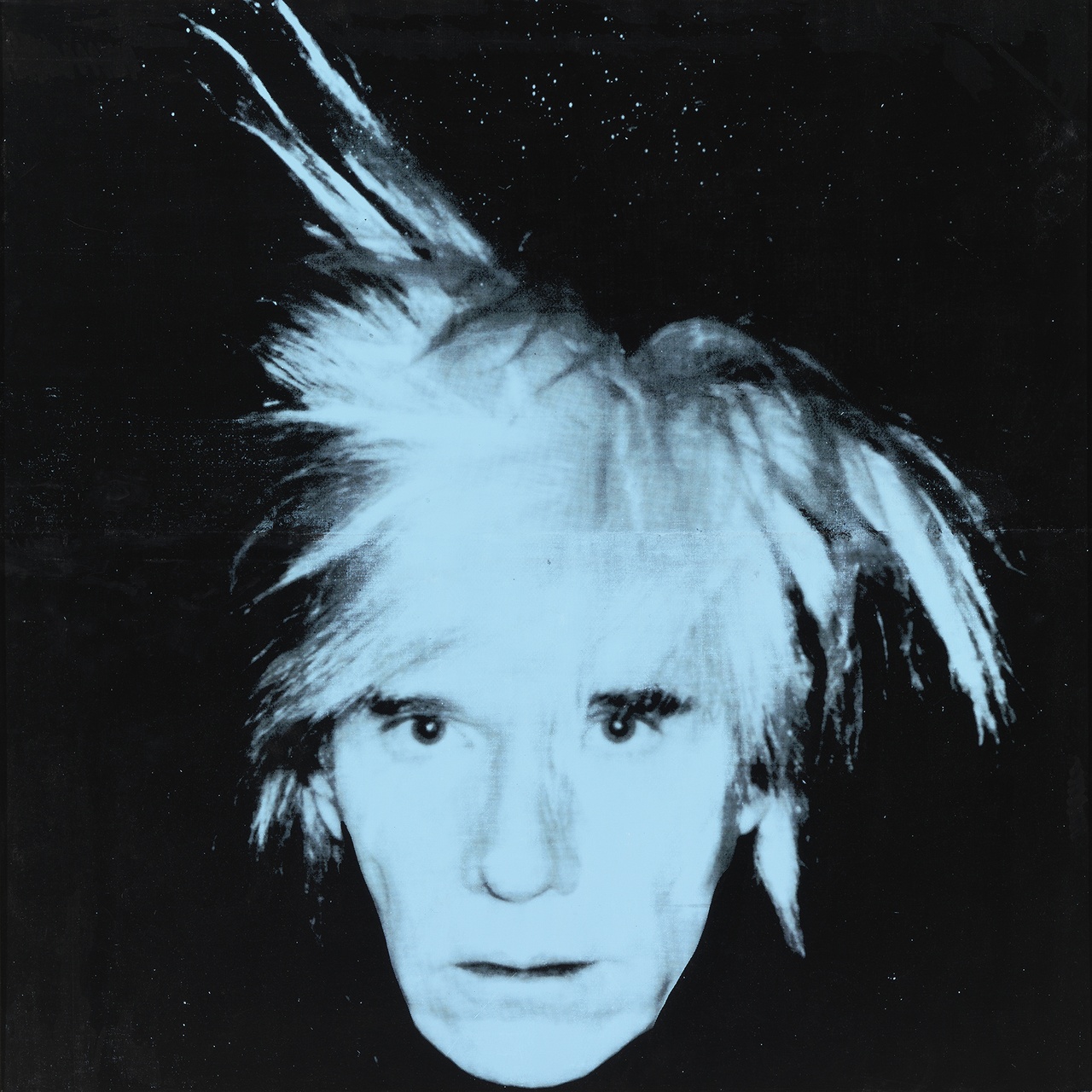

This fascination for a “hidden” Warhol also looms large at the Neue Nationalgalerie. Even though the Sex Parts and a few of the 1950s drawings shown were not exhibited during the artist’s lifetime, it would be mistaken to consider them as having been unseen. These works had their own small audiences of friends and insiders that complicate a clear-cut distinction between the public and the private. The eagerness to “peel away the layers of the artist’s public persona” and to “examine how his personal life and queer sexual orientation influenced his work” obscures how Warhol worked tirelessly to conflate the two. Though some aspects of his life remained more private (e.g., boyfriends, churchgoing), the revelation of personal life was a strategy the artist deployed consistently throughout his career. To frame the gay Warhol as previously “hidden,” as the exhibition at the Neue Nationalgalerie does, misses the opportunity to showcase the queer potential of his work. It has the power to blur the boundaries between private and public, innocuous imagery and sexual innuendo, straight and queer, and, consequently, it preempts neat distinctions between the visible and the hidden. A more complex play between different layers of meaning emerges, as long as the audience is receptive to its tone.

Simple images of bananas and splashes of paint lend themselves to double entendre, whereas buttocks and crotches appear as almost abstract divisions of the picture plane into color blocks. Look long enough at the Torso canvases (1977) that feature frontal views of a man’s groin, and you will be drawn to the edges of these color blocks by the peculiar placement of brushstrokes stitching them together. It is as if color field painting went through surgery and emerged with extensive scarring. To appreciate an image of the notoriously large penis of a ’70s gay porn star in this way strikes me as positively campy, and also as a distinct achievement of Warhol’s late painting technique, which places the screen print on top of a layer of casually gestural brushstrokes. The sometimes gorgeous surface effects produced by this method are ubiquitous in the paintings of this and the Ladies and Gentlemen (1975) series around which “Velvet Rage and Beauty” is centered. Yet, amid the resolute focus on content, this underappreciated feature of the late work goes largely unnoticed. However, the fluidity (and sometimes simultaneity) of queer and straight meaning is present in some of the curatorial decisions at the Neue Nationalgalerie, for instance, in the hanging of two photographs of The Wrestlers (1982) on the two marble-clad walls that adorn the otherwise austere exhibition hall. The association of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s marble with the stone butts of classical wrestler figures looks stunning and, more to the point, underscores the campy notion that “one can be frivolous about the serious.”

“The Party of Life” in Munich has its own frivolous moment: in the main gallery of Museum Brandhorst, a monumental canvas of Warhol’s Last Supper series (1986) enters into subliminal dialogue with a painting of two Converse sneakers (Converse Extra Special Value, 1985/86) on the opposite wall. The prominent shoes draw attention to the elegantly outlined feet of the apostles, uniformly dressed in flip-flops, that are placed firmly at eye level. To appreciate how male feet mingle under the supper table feels very much beside the point of the last supper as a biblical event, but it is front and center to Warholian sensibility, in which feet and shoes have been a subject of interest since the 1950s. On a manifest level, the Munich show treats Warhol’s and Haring’s homosexuality as a both glamorous and serious subject. In a room behind a silver string curtain, one finds a beautiful pairing of an Oxidation (1978) painting by Warhol with a photograph of a pornographic Sharpie drawing that an unknown draughtsperson put on the tinfoil that lined the walls of the Factory toilet in the mid-1960s. This unauthorized mark points to Haring’s subway drawings in the next room, while its subject relates to a small gold-on-black image of Haring’s typical cartoonish outlines of humans and dogs engaging in all kinds of sexual practices. The Oxidations, also known as piss paintings because they were made by urinating onto canvases primed with copper paint, are a notable absence in Berlin where, next to the stitched-up color fields of the Torsos, they could have brought the queerness of Warhol’s abstractions into view. In Munich, as one progresses from the piss painting through a succession of small, themed rooms, the focus quickly shifts to queer activism on the part of Haring and trans activist Marsha P. Johnson, whom Warhol portrayed in his Ladies and Gentlemen series. Warhol himself was, in the words of the artist Glenn Ligon, “not the out-in-the-streets kind of gay,” and the exhibition does not try to convince viewers otherwise. The delicate subject of Warhol’s at times exploitative practices and lack of any legible engagement with the AIDS crisis is not treated head-on but rather becomes obvious against the foil of the much more politically active Haring. A wall of posters the younger artist made in support of safe sex, ACT UP, and an end to Apartheid, among other causes, renders the single Warhol poster next to it a potent representation of this guarded approach to politics. Only when persuaded by Joseph Beuys did Warhol visually contribute to the first electoral campaign of the Green Party, of which the German artist was a founding member. The message is a simple endorsement in the same way he lent his name to brands like Absolut Vodka; Andy Warhol is also “für die Grünen” (for the Green Party). Warhol’s restraint in political messaging, however, should not distract from the fact that he was both a very public and a very queer person. He was also working-class, bougie, shy, enjoying the limelight, silent, chatty, commercial, and complicated. To deal with Warhol is to handle apparent contradictions with nuance and to come up with ways of keeping tensions in place instead of smoothing them over. Out of all three exhibitions, Museum Brandhorst does the most to enable what I have here called the queer potential of Warhol’s work.

Barbara Reisinger works as a researcher at the University of Stuttgart. Currently, she is preparing her monograph Malerei als Verkleidung. Andy Warhols Tapeten, 1964–1974.

“Andy Warhol: Velvet Rage and Beauty,” Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin, June 9–October 6, 2024; “Andy Warhol & Keith Haring: Party of Life,” Museum Brandhorst, Munich, June 28, 2024–January 26, 2025; “Andy Warhol: After the Party,” Fotografiska, Berlin, May 17–September 15, 2024.

Image credit: 1. © 2024 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, photo Haydar Koyupinar, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Museum Brandhorst, München; 2. + 3. Photos Elisabeth Greil, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Museum Brandhorst, München

Notes