IT’S NOT A PENALTY ’TIL THE REF BLOWS THE WHISTLE A Discussion About the Video Assistant Referee with Gertrud Koch, Max-Jacob Ost, and Volker Schürmann, Moderated by Leonie Huber

VAR system, Jupiler Pro League, Leuven, 2018

LEONIE HUBER: In popular usage, VAR (video assistant referee) refers to the person who analyzes game replays from video footage and advises the referee but also refers to the ensemble of images used for the analysis. The basis for this is the television coverage of a sports event and footage of it recorded in slow motion and ultra-slow motion. These are complemented by digital images generated by special computer-assisted ball-tracking technology, which is used for video review systems in football, rugby, cricket, and tennis. Cameras are installed around the field, then software calculates where the ball is located in three-dimensional space, on the basis of frame-by-frame triangulation from two-dimensional images. A subsidiary of Sony markets the technology under the name Hawk-Eye. The video assistant referees sit either in the stadium or in a remote location. What seems key to me is that these decisions are made off the field, and that no one sees the people who are communicating with the referee and checking the referee’s decisions.

GERTRUD KOCH: While everything I see in a film has already happened, a television broadcast shows the action in real time, with a slight technical delay. The interesting thing about VAR is the technical gap that opens up as soon as digital methods come into play. Accompanying the “past time” of film and the live time of broadcast, a third temporal layer emerges: based on a recording (i.e., image data), a calculation is run. And that calculation is relevant to the referee’s decision-making. Essentially, this is a statistical estimate of where the ball is, derived from the image data. Woody Allen’s Match Point (2005) is a film about the moment in tennis when you still don’t know whether the ball will clear the net. Digital techniques via pure computation can now resolve and standardize that moment.

What claim to reality does this computer projection have? Just the word alone suggests it’s about a higher level of knowledge than anything perceptible in real time. Triangulation breaks the evidentiary moment of a live game: The decision is routed through a third image space that interrupts the real-time broadcast and relies on a prior replay, stored in the control feed and technically modified. In fact, when the referee stops play and consults the remote review panel, the technology even interrupts real time. This uncoupling of space and time, so to speak, is an event that TV viewers no longer have any direct relation to. The epistemic stance shifts once viewers believe that the video assistants in the control room know more than what the on-field referee, the players, and the spectators in the stadium can see in real time. And from my perspective, as an outsider to sports, that changes the character of the event. As a game whose rules everyone knows and that everyone can participate in, even if not actively, a sporting event resembles a theatrical scene where the audience shares a direct presence with what happens onstage. What happens to the notion of sport as a game with shared rules when this technology gives way to a new situation, one that withdraws itself from layperson judgment?

Woody Allen, “Match Point,” 2005

MAX-JACOB OST: The reason this technologization has taken hold in football is that two parallel worlds have long existed: the stadium experience, which we experience live and judge in the moment, and the TV perspective, the first technical layer to break open the venue. Then there’s an additional temporal layer: the after-the-fact analysis of matches being repackaged for television. To this day, what we see doesn’t just depend on the camera lens or angle, but on the people who choose the footage. The growing tension between the stadium and TV experiences came about because viewers following the game at home had access to a supposed objectivity that wasn’t available to fans in the stands. People felt they only actually knew how a match had played out once they’d seen the TV footage. That tension manifested and erupted on the person of the referee when an on-pitch decision, when compared with TV replays, possibly proved to have been an error. Because football has become such a big business, the responsible parties were no longer willing to afford mistakes that were obvious to the television audience. The push to introduce VAR came from clubs and their governing bodies. What’s striking is that the so-called video evidence now fuses these two physically separate worlds while also adding yet another temporal layer. For now, this layer is accessible only to the video referees stationed in the VAR control room, the so-called Kölner Keller of the German Bundesliga. There they run constant checks: After every routine tackle, one assistant keeps an eye on the live action while another reviews two or three replays of the foul before deciding whether to intervene – or not, as the case may be. Fans in the stadium or in front of the TV don’t know which incidents are being reviewed or what calls are being made. So a modern football match is almost a multiverse. A goal is scored in the stadium, the fans hug, cheer, spill beer, but some of them are already wondering whether the goal will stand or be disallowed. Two scenarios play out in that sense: a celebration that proves premature, and the video referees’ verdict that, from their vantage point, no goal was scored.

VOLKER SCHÜRMANN: The two worlds have already moved closer together for quite some time now: Spectators in the stands could potentially follow the live broadcast on their phones. That created a legitimate pressure to act. After years of testing, VAR was introduced in the 2017–18 season simultaneously in the German, Italian, and Spanish national leagues before being written into the official rule book of the International Football Association Board a year later. I don’t think football culture would be saved just by abolishing VAR. At the same time, VAR feeds the illusion that you can prove what the truth is, that no decisions have to be made anymore, and that decisions should just be as objective as possible. The public perception and the debates usually gloss over this decision aspect. What needs to be challenged is the claim that a video-assisted ruling carries conclusive force.

Andy Murray, Wimbledon Championships, London, 2015

KOCH: These technologies are applied at a functional level to optimize workflows. So we’re seeing yet another round of professionalization in popular sports that once began as amateur sports. The technology is also used to boost professional athletes’ performance through error analysis. In fact, there are huge financial investments at stake here. You could say it’s a pretty routine mechanism for monitoring workflows. So in relation to VAR, a sociological question arises: Is this the form sport takes under digital capitalism – namely, a functional differentiation of professional sports? And beyond that, does the double structure we’re talking about stem from the fact that TV rights have been the clubs’ main source of revenue for such a long time already, and that this demands a broader division of labor involving these technologies? A given game situation, a given sequence of actions, is simultaneously recorded, broken down into split-second fragments, and rendered repeatable. Essentially, a layer of evaluation is introduced to the game that wouldn’t be possible without these technologies. To me, the development lies in the fact that the sport’s modes of presentation and its practice are being differentiated in technical media. We then have to understand technologization not just as a special effect of football broadcasting but rather as a form of professionalization within digital culture.

HUBER: What’s crucial about VAR, though, is that its footage is used to challenge decisions. A second authority to review referees’ calls was first proposed in a 1997 article in The Australian newspaper. In that piece, Senaka Weeraratna, an attorney, sketched what would later be introduced to cricket in 2009 as the decision review system:

Patently wrong umpiring decisions are allowed to stand because of the absence of a mechanism in the laws of cricket to overturn them. In the judicial system a dissatisfied litigant has the right of appeal against the decision of the judge to a higher court or a full bench. A similar principle of appeal should find expression in cricket rules and allow a dissatisfied captain to appeal against a ground umpire’s decision to the third umpire. [1]

In Weeraratna’s argumentation, it’s obvious that the video assistant referee is a reaction to the differences among various perceptions of what happens during a game.

A difference in how the video review system is used in cricket compared with football is that in the former, it’s not just the third official, off the field, who can contest a decision. The players themselves can call for a review, too. There is also what’s referred to as the umpire’s call, which questions the authority of the video evidence and asks the umpire to deliver a final ruling. This is a speech act that challenges whether what appears in the image matches reality. The legal aspects of VAR come to the fore here. Similarly, it’s been introduced into football, to review “clear and obvious errors and serious missed incidents.” [2] The scope of that rule reads like a list of criminal offenses.

Protests against VAR, 2020

SCHÜRMANN: There’s no doubt that sport today is shaped by digital capitalism. But because we’re talking about modern, differentiated societies, that act of shaping is always ruptured by the logic of each particular field. Which is why we’ve got to remember that VAR is a tool to review decisions in athletic competition. In so-called street football, there are no referees; the teams just negotiate among themselves and over the rules. When the decisions are delegated to a separate third party, that party’s authority rests on being accepted by both sides. There’s an analogy with court proceedings here, which represent an advance on feudal self-administered justice. This core idea of modern societies is simulated on the pitch. The lack of an appeals body was a problem that needed a better answer than just saying people make mistakes. When refereeing errors were immediately obvious, the referee’s authority needed to be strengthened as a precondition for them to even be able to continue in the role.

KOCH: For me, it’s always been clear that football’s a game. That’s where I see its link to the aesthetic dimension of sport. In your argument, Volker, you’re totally right to emphasize that it’s an athletic competition. Unlike a game, a competition is only about winning and losing. Alongside that, there’s the professionalization of kids or teens kicking a ball on a field – perhaps already with the desire to be discovered – into specialized careers and expert roles. The referee, as an independent figure who sees the game from outside, is an expression of that professionalization. And that function is now delegated to the cameras, which effectively act as witnesses. That substantive description matches what you, Volker, are describing. Normatively, though, there’s a difference between a game and a competition, yet these two spheres overlap.

OST: In its early days, football was a sport in which the rules had to be defined before every match. At some point, the rule system was institutionalized. The game became a competition and, in industrialized football, a form of mass entertainment. There’s an essential distrust of the human being here, which is why teams no longer trusted each other to reach a fair decision in contentious situations. So they brought in a third party: the referee. Which was a systemic flaw from the standpoint of democratic theory, because they play the judiciary and executive roles in one person, and in earlier times, they were even the legislative, too. Some referees interpreted laws so freely that they essentially acted as lawmakers. Which means that in football, unlike in other sports, the referee wields massive power. In cricket, an almost legal question arose: Who can be the plaintiff, who can be the defendant, and who renders the verdict? For a long time, that was unthinkable in football, because everyone had grown accustomed to the all-encompassing power of the referee’s position. At the same time, distrust of human beings runs so deep that when there is a choice between a human judgment and a machine one, in many social spheres the machine will be preferred. People presume that technology makes fewer mistakes – or at least makes mistakes that can be reproduced. Football fans don’t care about frame rates or the difference between frame A and frame B. But that difference is crucial for determining the offside line: What counts is the instant the ball is played. If that instant falls between two frames, there’s currently no technical method for determining it. As early as 2020, a study showed that this inaccuracy can place a striker several centimeters farther forward or back, making them seemingly offside in the images, even if they might not have been in reality. [3] In other words, the technology offers us only a simulated truth, even on a mechanical level.

Football is by nature a game riddled with mistakes. Its very essence lies in a play going wrong. The appeal comes from how much harder it is to control a ball with the foot than with the hand. But paradoxically, the economic importance of the sport means that we can’t permit the referee to make mistakes.

Lucien Davis, Original English Lady Cricketers, Daisie Stanley batting (illustration for “The Illustrated London News”), 1890

How does the media present the process of making judgments in sport and in sports reporting? How do they draw on the storied TV tradition of presenting courtroom trials as spectacles? And what learning effects emerge from this? Court dramas are a classic TV format where viewers find themselves in the peculiar situation of witnessing an allegedly real trial and are being cast in the role of judge. Like with a live broadcast of a football match, this kind of reality TV doesn’t define whether the viewer is the defendant, defense counsel, prosecutor, or judge. The authoritative spirit that is regulated in legal proceedings – namely, that the judge has the final say – is absent here. A narrative situation – and jurisprudence is a form of this, too – engages spectators’ emotions and affections. How does one assess the deed set in motion by various roles and actions? VAR provides an answer to this question by establishing an objectivity that, through the allocation of media roles, is then taken on by technology that can no longer be challenged and retains a final say that otherwise would have been reserved for the judge.

Marie Wegman argues with the umpire Norris Ward, Florida, 1948

SCHÜRMANN: It isn’t a court proceeding, but it gives the impression that the referee is performing all three roles simultaneously. A match is different from a court trial in that it can’t just be paused or postponed. The game has to be decided within a set time, which makes it impossible to have a review by a second authority. The spectators play a key role here: It just gets so uncomfortable when the crowd unleashes a hellish chorus of boos. Uncomfortable in the mildest sense of the word. These may not be severe penalties, yet the crowd, players, and referees still hash out the fairness of the call. This form of justice is woven into what we call football culture. Fan protests and debates over intentional or accidental handballs aren’t isolated incidents; they’re part of a broader conversation about whether the rules need changing. And that’s the fans’ role in the process, to exert pressure on the rule system.

KOCH: When I consider the introduction of VAR from a normative perspective, other questions arise. Like, do we want to treat this highly specialized professional sport as an economic enterprise? I’m interested in the broadcast of a football match as part of TV culture and in how it’s woven into other genres and formats in which a similar aesthetic of technologization recurs, again drawn from these quasi-judicial forms. What cultural forms emerge here, and what do they reveal about the spectators and, ultimately, about mass consciousness? What image of fair judgments does this convey? What I’m saying is that it presents the image of an automated judge who allegedly decides without person or preference. It’s exactly the same thing that artificial intelligence is now offering: They analyze all past judgments to calculate which decision is statistically most probable. Somewhat simplified, this is how VAR can be placed within the history of automation and mechanization. I would argue that this trend isn’t just confined to individual fields like sport or the legal system; rather, it’s part of our entire society as an expression of digital capitalism. [4]

Wolf Citron and Ruprecht Essberger, “Das Fernsehgericht tagt,” 1975

SCHÜRMANN: When I spoke of normativity, I wasn’t referring to the question of how we want sport to be or what we think of sport as it is now. Rather, I meant that the legal dimension we’ve been discussing is itself normative. It’s about making a fair decision. That’s the challenge that was behind the introduction of VAR. It’s tied to digital capitalism, but it doesn’t stem from it: It stems from the question of fairness. This fundamental idea is reflected in modern football as a TV spectacle, even though it is warped in arbitrary ways compared with kids playing on a field. The premise is that it’s not predetermined who will win and who will lose. It’s also about whether the game is valued purely for its entertainment or preserved as a cultural phenomenon with its own ideas and logic. And I take a normative stance here: For me, it’s about preserving a core principle of sport. One lever is making clear that despite the video “proof,” it remains a decision, a decision about fairness. Can we entrust that to algorithms? Do we want to? What data is fed into those algorithms, and what reality does it produce? A chess computer cannot play fairly.

HUBER: It is important to emphasize that VAR in football isn’t automated: Human beings analyze the footage. It’s different in tennis, where the Hawk-Eye technology is mostly used to determine whether a ball is out or not. Back in the 1970s, they were already trying to make line judges’ calls fairer and less susceptible to human error. In 1980, they introduced a computer-based system called Cyclops, which used infrared beams a few millimeters above the line to determine the ball’s position. After several clear errors by the line judges in Serena Williams’s 2004 US Open quarterfinal, the International Tennis Federation began trialing so-called electronic line judges, and by 2006, they had introduced Hawk-Eye for international competitions. Initially, it was a standard procedure for players to challenge line-judge calls made via triangulation-generated images, but now all Grand Slam tournaments – apart from the French Open – exclusively use electronic line-judges. In Paris, where they play on red clay, the ball leaves a visible mark, so if there’s any doubt, the line judge hops down from the chair to check the clay imprint.

This is an example of the performative dimension that distinguishes sport as a cultural form. In football, the referee goes into the referee review area to view the “evidence” on a monitor. The recurring image here is one of human and machine facing one another. In rugby, the communication between the on-field referee and the third official, known as the television review system, is broadcast live into the stadium, for example. The goal is to ensure transparency but also to humanize the process.

We’ve spoken about technical images, the distinction between on-site spectators and television viewers, the legal dimension of decision-making, and the aspect of fairness. What unites all these is the technical image’s claim to objectivity. A view of the proceedings unclouded by human subjectivity – that’s what Hawk-Eye claims.

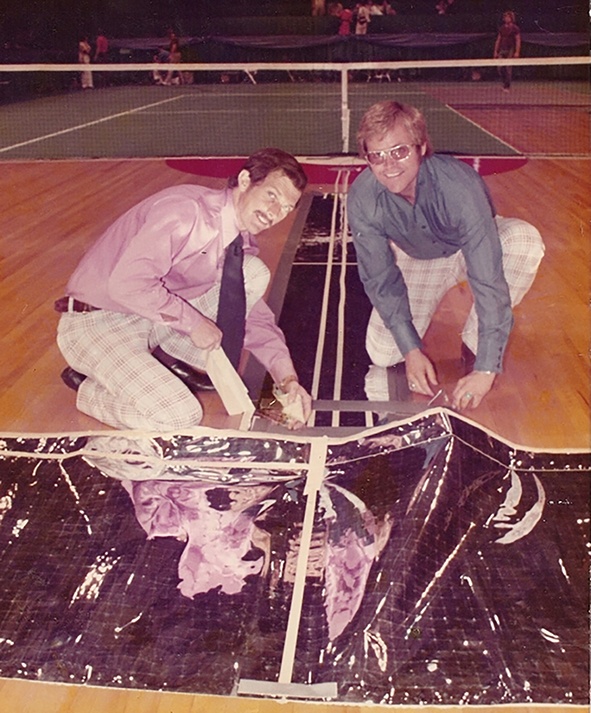

Geoffrey Grant and Robert Nicks with their invention, the “Myler Sensors,” 1976

KOCH: The animal metaphor of Hawk-Eye – which implies a link between camera optics and a human gaze – falls flat when it comes to the digital technologies that analyze the images. Objectivity no longer resides in the gaze – the visual witnessing of “having seen” – but in information. And that information is determined through a technical operation, channeled in the literal sense. Niklas Luhmann defines information as that which is crucial, whether I have it or not. In digital theory, two modalities intertwine: Information is sent through channels to produce a recording in which you can see exactly where the ball was, and that information can then be distilled from the image. That is one, information-based, concept of truth. Then there’s a second truth, arising from computational processes when the images are analyzed and something is calculated that does not in fact exist as an image. And it’s this calculation that is subject to this peculiar structure of time. There’s nothing inherently scandalous about reaching a judgment this way. But it gets even more difficult to understand what led to that judgment, because we cannot master the machine languages being used, nor can they be translated for lay audiences. For us, only the results expressed as numbers remain readable.

SCHÜRMANN: We are dealing with a very specific notion of objectivity that leaves no room, even broadly, for any legal or cultural dimension. All human factors are always on the subjective side, so an objective ruling by referees/judges is out of the question, as they will always carry bias. This is the foundation, from the philosophy of science, of what Max described earlier as a distrust of human beings. The idea that VAR helps arrive at an objectivized fair decision – because the technical image just can’t be reduced to a piece of information – never plays a part in the debates about VAR. The problem isn’t in technologization itself; it’s in the cultural side effect of claiming that VAR can replace human judgment, rather than just support it.

Serena Williams, US Open, New York City, 2004

This information-based truth, generated by transforming pixels into data and then into an image, is even taken a step further when the results are presented. The simple decision – if, say, a football’s full diameter is behind the goal line, then it’s a goal – could already be made based on other goal-line technologies. The aesthetic presentation of triangulation-generated data has changed, and a standard has now emerged: All people are removed, leaving only the ball seen from an angle no camera setting could provide. I find it interesting how relieved the crowd is by this simulation of truth: “Oh well, the ball just barely brushed the line, it’s not a goal,” essentially. Even though no one in the stadium or watching on TV actually saw it or could say whether the calculation was accurate. We don’t trust our own eyes, nor do we trust the referees and line judges. We trust the computer-generated graphic.

KOCH: An age-old strategy in evidence generation is to bind affect with images. The close-up was the key element in cinema history here. Gilles Deleuze dubbed these “affection-images,” and I think what we see with VAR are pretty similar visual effects. The moment the ball is shown in isolation, separated from the action, it becomes the decisive actor. An autonomous legal subject, so to speak. And all that affectivity is bound up in the shot where I see the ball up-close in the image. That’s the evidential proof. What are we actually seeing? How does the viewer respond to these visual proofs? A similar thing is interesting to me in theater and opera productions that, over the past 20 years, have incorporated videographies of the onstage action. It’s a perceptual-cultural phenomenon, where attention is drawn to an actor’s face in close-up, which can be seen projected onto a screen above the stage.

SCHÜRMANN: This discourse is part of a modern debate in the philosophy of science. A climate has been created in which what is computable is regarded as self-evident. Some find calm and relief in that, whereas others complain that VAR is killing the game. It seems a fair question to me whether the “proof” that the knee was a few millimeters offside is actually what we find interesting about the game. Debates like those over VAR still hinge on whether we allow images to make the decision for us – and in turn, I find that quite reassuring.

KOCH: Absolutely. You could say it would be the triumph of measurement techniques as a means of producing reality.

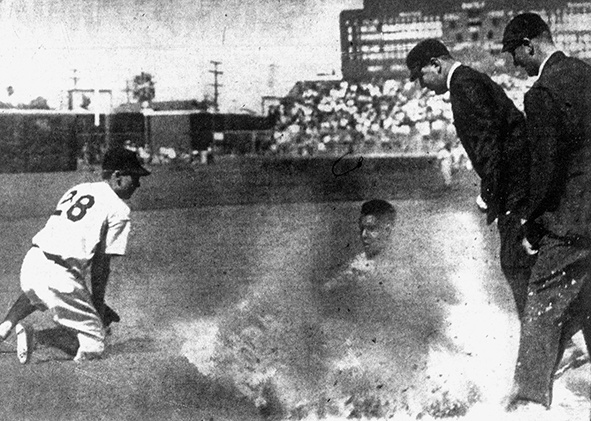

Gene Baker slides safely into third base, Los Angeles, 1953

HUBER: In a 100-meter race, no one would question whether or not it makes sense to measure who crosses the finish line first. If there were no technical measurement, there’d be no sense in hosting the athletic competition. So it also depends on the role evidentness plays – however one may conceptualize it – within a given sport as a cultural phenomenon. The catharsis and reassurance a lot of fans get from VAR is also the pacification of two opposing parties locked in conflict over a particular incident. But the affect these conflicts ignite doesn’t end with VAR. The debates over VAR might even reflect how the contestability of decisions is an inherent part of football. The moment someone believes they know something objectively, all the fun is gone, along with the meaning fans invest in it.

OST: Affect is central to football – not just on the pitch but also in the stands. The biggest complaint about introducing VAR was that it would take the emotion out of the game. The fact that a decision can be overturned actually does change how you emotionally react to a goal. But VAR replays themselves also stir up affect.

The aesthetics of football broadcasts have constantly evolved: from radio to black-and-white TV, to color TV, and most notably through replays. Broadcast producers always watch for moments when play pauses. Then they choose which camera angle, replay, or close-up to show. These affection-images play a major role in otherwise fairly standardized broadcasts: The ball always has to be visible, and a certain number of players have to appear on-screen. With the introduction of VAR, directors faced the challenge that they didn’t have access to the footage while still needing to keep the referee in view in case they make a gesture to signal a decision. The solution was a split-screen, showing replays of the disputed incident on one side and the referee with a hand to their ear on the other. It’s only afterward that the camera angle that the video referees base their decision on is relayed from the server to broadcasters. So it isn’t just an interruption of play in the stadium; it’s a rupture in the game’s aesthetic. For a lot of people, it’s a change to viewing habits they learned in childhood. A football match is reproducible and looks essentially the same, with only minor variations. And that’s one more reason VAR has generated so much excitement and resistance.

Translation: Matthew James Scown

Leonie Huber is an editor at TEXTE ZUR KUNST and a football fan.

Gertrud Koch has been a professor at the Department of Film Studies at Freie Universität Berlin and is currently a visiting professor at Leuphana Universität Lüneburg.

Max-Jacob Ost has been reporting on the men’s and women’s Bundesliga matches, as well as the timeless and societal topics related to soccer, in the podcast Rasenfunk since 2014.

Volker Schürmann is a professor of philosophy, in particular sports philosophy, at the German Sport University Cologne.

Image credits: 1–4. © Alamy; 5. Illustrated London News, public domain; 6. Public domain; 7. © Alamy; 8. Public domain; 9. © Alamy; 10. Public domain

Notes

| [1] | Senaka Weeraratna, “Third Umpire Should Perform the Role of the Appeal Judge,” The Australian, March 25, 1997. |

| [2] | See IFAB, “Video Assistant Referee (VAR) Protocol,” International Football Association Board. |

| [3] | George Mather, “A Step to VAR: The Vision Science of Offside Calls by Video Assistant Referees,” Perception 49, no. 12 (2020): 1371–74. |

| [4] | On the connection between measurement procedures and the automation of labor, see also Matteo Pasquinelli, The Eye of the Master: A Social History of Artificial Intelligence (Verso, 2023). |