DRAWING BLOOD: MATTHEW BARNEY’S PERFORMANCE REGIMEN JULES PELTA FELDMAN

Matthew Barney, “SECONDARY,” 2023

Sports and art share an essential condition, that of being fundamentally inconsequential. Like theater, sports are circumscribed in what Johan Huizinga called a “magic circle,” a space set apart from normal life by its rules and roles. [1] Whatever takes place within the circle, so Huizinga, can have no meaningful consequences beyond it. Theater and other forms of art are also, like sports, related to play and games; play is “something we do not out of necessity but for love: freely undertaken, it allows us to shed the constraints of everyday survival.” [2] Prior to the 19th century, however, the English word sport referred primarily to hunting – bloodsport – whereas game was a living creature, and unlike theater, the play ended in its death. [3] The surrealist Michel Leiris yearned to turn his writing into an arena as exciting and dangerous as that of the bullring. “For the torero there is a real danger of death,” he wrote with strange longing, “which never exists for the artist except outside his art.” [4] Yet just as bullfighting violates sport’s identity as mere play, so, too, is there a form of art that affords the artist a taste of real danger: performance art. Performance distinguishes itself from theater by foregrounding genuine risk, struggle, and uncertainty. [5] For this reason, sport’s structure – rule-bound, recognizable, yet excitingly unpredictable – offers a model not only for understanding performance’s relationship to the magic circle but also for preserving its immediacy across time.

Matthew Barney, “Patriot,” 2024

If bullfighting’s deadly drama transgresses our understanding of sport as mere play and performance as theater, then we might begin to make sense of the artist Matthew Barney’s enduring obsession with gridiron (North American) football and its potential for bodily transformation. Those with even a passing familiarity with Barney’s work will have observed the perplexingly central place of petroleum jelly, that inorganic, beguilingly semitranslucent ointment marketed under the brand name Vaseline; in fact, Barney adopted it from his days as a young quarterback, when the stuff was smeared liberally on and in points of friction and vulnerability: thighs, wounds, orifices. In particular, it was used to ease the contact between the athlete’s body and his extensive equipment, which the artist understands as a form of prosthesis. He speaks of the experience of

Matthew Barney, “SECONDARY,” 2023

Football is perhaps better known, however, for another method of physical transformation: that of violence. Injuries can and do take place in all sports, but they mar the game – break the circle. Yet in football, as in bullfighting, violence is essential to play.

Barney played football from the age of 10, grew up in its regimens and rituals, and has consistently incorporated those systems into his art – from his earliest Drawing Restraints of the late 1980s, which were exercises in artistic resistance training, to 2023’s SECONDARY, a suite of sculptures and a five-channel video installation that features a slow-motion dance reenactment of one of the sport’s most gruesome injuries. In 1978, when Barney was 11 years old and fresh to the game, Jack Tatum, defensive back for the Oakland Raiders, collided with New England Patriots wide receiver Darryl Stingley, shattering two of Stingley’s vertebrae and thereby rendering him permanently quadriplegic. The move was perfectly legal, and Tatum – already nicknamed “the Assassin” for his brutality on the field – never apologized. [7] A friend of mine who played high school football (and whose body, decades later, still bears the marks of it) recalls being repeatedly reassured that “injury is part of the game.”

Matthew Barney, “C.T.E. Snake,” 2024

For SECONDARY – the title refering to the collective noun for the defensive backs who work to prevent opposing receivers from catching the ball – Barney worked with choreographer David Thomson, who also performs as Stingley, to restage the fateful encounter between Tatum’s head and Stingley’s neck. This is not a forensic reconstruction of the event but rather a registration of its impact on Barney’s consciousness, a jolt to his brain beyond those he received on the field. In the video, performers dressed in football uniforms execute repetitive exercises and creative tasks in Barney’s large warehouse studio. Tatum and Stingley, 30 and 26 at the time of their collision, are played by the aging dancers Thomson and Raphael Xavier; Barney himself, now in his late 50s and sporting a gray beard, appears as Raiders quarterback Ken Stabler. As Tatum and Stingley approach each other, a sticky, gelatinous mass of vaguely pinkish goo (this is Matthew Barney, remember) seems to emerge from the space between the two dancers’ bodies and bounce onto the ground, rendering the negative space between them as fragile visceral matter. Barney’s Stabler falls down again and again, trapped melancholically in moments of physical trauma (Stabler, along with Tatum and hundreds of other players, was diagnosed postmortem with chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE). In one scene, he scoops the soft innards out of a football helmet and tapes them to his head, emphasizing the cushiony forms that adapt the human body to this smooth, hard exterior shell. A related drawing from the project, C.T.E. Snake (2024), seems to offer the viewer a peek into Stabler’s head as he lies on the ground (“Snake” was his nickname). Along with the man’s spine and brain, we also see the guts of his helmet, the padding that failed, along with his own skull and cerebral fluid, to protect him from his sport. (While football helmets protect against skull fractures, they have historically, as one scholar of brain injuries has put it, “been superbly designed as concussion delivery systems.” [8]) That padding is often made of high-density polyethylene foam, which Barney used here for the drawing’s frame – an empty talisman of protection, given Stabler’s exposure to the viewer.

Matthew Barney, “SECONDARY,” 2023

Football, like bullfighting, is a game that is not a game. As Roland Barthes said of the latter,“This theater is a false theater: real death occurs in it.” [9] Indeed, what is often seen to separate performance art from theater is the principle of real risk. In Barney’s personal mythology, one of his many alter egos is Jim Otto, the Oakland Raiders center whose capacity to endure physical punishment during a “performance” rivaled that of Gina Pane, Marina Abramović, or Bob Flanagan. (Otto never missed a game because of injury, despite over 70 surgeries related to injuries on the field, which led to near-death experiences, a complete set of prosthetic knees, and, eventually, the amputation of his right leg.) Abramović has famously defined her medium in those terms: “In theater, the knife is fake and the blood is ketchup,” she declared, while “in performance art, the knife is real, the blood is real.” [10] Abramović is known for placing herself at great risk of physical harm, such as in Rhythm 0 (1974), when she invited her audience to apply various objects – among them a scalpel, a thorny rose, a pair of scissors, a loaded gun – to her body. In Rhythm 10 (1973), adapting the form of an old game for those who like to play with danger, she stabbed knives between her outstretched fingers, incorporating each accidental cut into the score for a second round. As for Otto, injury was seen as an unscripted but inevitable consequence, certainly no reason to leave the magic circle.

Performance art, which tears the decorous veil that separates art from life, can be understood as an attempt to actually take on risks that have traditionally served purely metaphorical purposes in art. Yet Barney has made liberal use of “ketchup,” often relying on the kind of latex-and-makeup special effects used in monster movies. His best-known works, the five films of the *Cremaster Cycle* (1994–2002), do include athletic feats by the artist – most memorably, as Cremaster 3’s tartan-clad, bloody-mouthed “Entered Apprentice,” he scales the interior walls of the Guggenheim, dodging globs of hot petroleum jelly hurled by Richard Serra – but these have been subordinated to story, their success or failure determined not by Barney’s bodily ability but by the narrative demands of his abstruse allegories. The kind of risks that Barney took on the gridiron – risks that were made crystal clear following the 1978 incident – he has mostly avoided in his art. SECONDARY represents a more symbolic approach to what Barney called his younger self’s “narcotic relationship to impact” – that is, “being hit, and hitting.” [11] Violence is not a side effect of football; it is inherent in the performance. “The young people that are coming out and playing football today,” Otto said in 2012, “if they enjoy hitting somebody, let them hit people; let them play football. If they don’t enjoy it, then they should play soccer or they should play something else.” [12] (Otto, too, was found to have CTE.) Unlike the bullring’s “false theater” where real death occurs, SECONDARY only dramatizes the moment when the magic circle is broken.

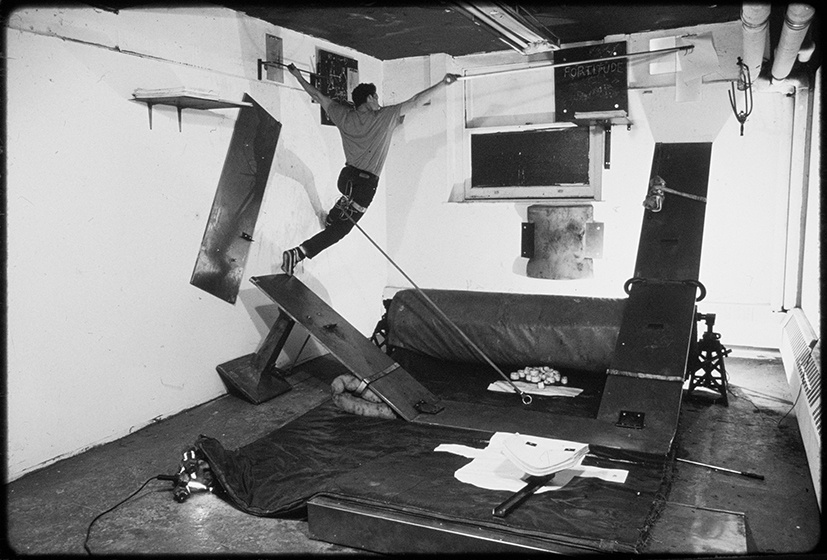

Matthew Barney, “Drawing Restraint 2,” 1988

But while SECONDARY’s violence is simulated or suggested, Barney’s earliest works are predicated on the precarious drama of live performance, in both the athletic and aesthetic sense. The first six Drawing Restraints, made while the artist was an undergraduate at Yale, are straightforward exercises in physical discipline that he documented in soundless black-and-white video. Barney has explained these works as an attempt to reach creative hypertrophy, the process of muscular trauma and repair that builds strength through stress. Barney makes use of tilted platforms, ropes, elastic bands, trampolines, and heavy weights – devices adapted from the training regimens he had undergone as a young athlete – all of which push him to work his body harder in the attempt to produce drawings that are really only, to adopt Barney’s metabolic vocabulary, a byproduct of the process. The point of the early Drawing Restraints is not to make something (non productivity being another quality, incidentally, that Huizinga identifies with play) but rather to do something: to try and quite possibly to fail. “I always think of those videos as only a possible narrative of what might have happened in that space,” Barney has said; each one explores “how an action can become a proposal, rather than an overdetermined form.” [13] This approach aligns the Drawing Restraints with Abramović’s Rhythm 10, in which accidental patterns come to define the work. It also means that any of the Drawing Restraints could be re-created but never repeated. They thus imply their own continuity – not in the fixed sense of a video but in the live, open sense of a game. In this way, Barney’s work points to a broader proposition: that sport, with its repeatable form and irreducible contingency, offers not only a model for performance but a model for its ongoing vitality.

Scholars of performance have criticized the re-performances of Abramović for being too rote – too much like traditional theater, perhaps, with its scripted action and foregone conclusions. Yet it may be that sport offers a better model for the longevity of performance art than theater does (or at least for those performance works, like the Drawing Restraints or Rhythm 10, that exploit goal-oriented, sportsmanlike effort). A sports match is always the same – indeed, referees ensure that it always proceeds according to the same rules – and yet it is always unique, unpredictable, exciting. The repetition of sport only emphasizes its fundamental contingency. If performance art is to remain alive – not merely archived, restaged, or reenacted – it must reckon with the kind of structured unpredictability that it shares with sport: where repetition breeds new possibilities, and real bodies bear real stakes.

Matthew Barney, “Dynamic of Internal Relation,” 2006

With its explicit references to football’s lasting damage, SECONDARY may seem more closely allied to the sense of danger and possibility that Leiris romanticized in the bullfight. Yet in their structure and form, Barney’s Drawing Restraints are much more game-like and therefore riskier. They represent a particularly useful test case for this model of recapitulating performance since they make literal the symmetries between athletic and aesthetic performance. Unlike his performances on the field, or the matador’s in the ring, the Drawing Restraints do not draw blood. Yet in some ways, they are Barney’s most dangerous works. SECONDARY, despite its significant aesthetic ambitions, avoids football’s bodily risks, but in plumbing the sport’s depths, it is evidence that Barney has never shaken off the obsession with risk that characterized his earliest works. And in this light, sport – bloody or otherwise – offers not a metaphor for performance but a method for keeping it alive.

Jules Pelta Feldman is an art historian, critic, curator, archivist, and salonnièr*e. They teach at California College of the Arts in San Francisco.

Image credits: 1. © Private Collection and Mathew Barney, courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, photo David Regen; 2. © Matthew Barney, courtesy of the artist, Gladstone Gallery, Sadie Coles HQ, Regen Projects, and Galerie Max Hetzler; 3. © Private Collection and Mathew Barney, courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, photo David Regen; 4. © Matthew Barney, courtesy of the artist, Gladstone Gallery, Sadie Coles HQ, Regen Projects, and Galerie Max Hetzler; 5. © Private Collection and Mathew Barney, courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, photo David Regen; 6. © Private Collection and Mathew Barney, courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, photo Michael Rees; 7. © Private Collection and Mathew Barney, courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, photo David Regen

Notes

| [1] | Johan Huizinga, Homo Ludens (Taylor and Francis, 1949), 10–11. |

| [2] | Jennifer Dunlop Fletcher, Seph Rodney, and Katy Siegel, eds., Get in the Game: Sports, Art, Culture (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2024), 19. |

| [3] | Steven Connor, A Philosophy of Sport (Reaktion Books, 2011), 25–30. |

| [4] | Michel Leiris, “The Autobiographer as Torero,” in Manhood: A Journey from Childhood into the Fierce Order of Virility, trans. Richard Howard (University of Chicago Press, 1992), 157. |

| [5] | This is an egregious oversimplification, but still a useful one. |

| [6] | Hans Ulrich Obrist, Matthew Barney (Walther König, 2012), 79. |

| [7] | The NFL subsequently sharpened its rules against violent hits, but since Tatum did not lead with his helmet or crash his head into Stingley’s, the play would likely not be flagged today. |

| [8] | Stephen T. Casper, “From ‘Punch Drunk’ to CTE: How the Sports World Learned to Ignore Brain Trauma,” Global Sport Matters, February 10, 2022. |

| [9] | Roland Barthes, What Is Sport?, trans. Richard Howard (Yale University Press, 2007), 3. |

| [10] | Marina Abramović and James Kaplan, Walk through Walls: A Memoir (Crown Archetype, 2016), 337. |

| [11] | “Interview of Matthew Barney,” posted July 11, 2024, by Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, YouTube video, 11:10. |

| [12] | Tom Jennings, “Jim Otto – League of Denial: The NFL’s Concussion Crisis,”, Frontline, PBS, December 22, 2012, video, 30:05. |

| [13] | Matthew Barney and Thyrza Nichols Goodeve, “Travels in Hypertrophia,” Artforum 33, no. 9 (1995): 68–69. |