PERMANENT SELF-REPRESENTATION Anna Sinofzik in Conversation with Henrike Naumann

Henrike Naumann in her installation “Ostalgie,” Busch-Reisinger Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, 2024

ANNA SINOFZIK: One of this issue’s theses is that the gallery system is currently exposed to strong pressures and that this is manifesting as a loss of trust in existing structures. You’ve managed to establish a successful, institutionally visible position as an artist, more or less independently, without long-term gallery representation. Given your background – and by that, I mean both your education taking you from applied art to fine art and your upbringing in the GDR – the fact that you represent yourself as an artist seems plausible to me. Ultimately, it’s not just that you’re familiar with another (art) system you’ve also been trained in disciplines of creative labor that work differently from fine art. For you, what is your model drawn from? And did it take shape over the course of your career, or is it the result of a deliberate decision, taken at a particular moment?

HENRIKE NAUMANN: It was a mix of two things, I think: Certain experiences led to a decision – and then, in turn, to the conviction that I’m simply the best person for the job of representing me. Those biographical elements of mine you mentioned play a significant role in that. I began studying stage and costume design for theater, then moved on to scenography for film and TV. So I learned my way around a bunch of different models of artistic labor. Maybe it’s because of that background that even from the very start, I was less centered on the typical ideal of an art career. For a lot of fine art graduates, entering the market right after graduation is a thing to strive for. I questioned the mechanisms of this market pretty early on. And that definitely has something to do with my growing up on a different understanding of art. In the GDR, art was something public, as widely accessible as possible – it had a social mission. It was only later that I became familiar with the art system in the West.

SINOFZIK: You were represented by Galerie KOW from 2017 to 2021. How do you look back on that phase?

NAUMANN: With KOW, I had a gallery I felt comfortable with politically. It was a productive collaboration. But it got increasingly obvious over time that it wasn’t a fit for me – not so much that particular gallery as the system as a whole, which just doesn’t work for my practice. Because I want to be involved in the entire process and shape it myself, including the economic aspects. At the same time, I noticed that a ton of what gallery representation promises – stuff like participating in art fairs or placing work with private collections – wasn’t something I actually wanted at all. I’m not interested in having my installations monetized quickly or in how they could be pieced apart to sell better. What matters far more to me is keeping each work intact in all its complexity and in its entirety, placing it in a museum collection that makes it as accessible to the public as possible.

Henrike Naumann, “14 Words,” MMK, Frankfurt am Main, 2018

SINOFZIK: A lot of galleries also work very hard to get their artists institutionally established and are often the crucial link to institutions. And when it comes to access, you could argue that there’s a cost on that front when you opt out of gallery representation. In Berlin, the free admission on Museum Sunday has just been scrapped. Galleries don’t charge admission fees; a large family can go there to see art for free, technically even several days of the week. Galleries also create social settings, and while these aren’t necessarily inclusive, they still enable specific interactions and discussions.

NAUMANN: That’s true, but my work often has a strong connection to place; it engages with the institution and its context. Unlike with a gallery – a white cube that tends to be detached from social life, or at least tries to be – what interests me in social and public structures is specifically that embeddedness. Galleries also sell to institutions, obviously, but I’m confident I’m the best person to get my work into the right places. I have the staying power, and when it’s needed, I can make decisions that might not make financial sense at first – like, instead of selling a work right away, keeping it in storage for two years and then placing it where I see it in the long term. The collection a work is included in influences whether and how it becomes part of art history. And of course, as an artist, I have more interest in that than my gallerist does.

SINOFZIK: It seems to me that the approach you describe also correlates with the material makeup of your installations, with the fact that you work with everyday objects and address ideologies that give the broader public a point of entry. You draw on art historical references too, of course, but your work doesn’t require the specialized knowledge of art history. Unlike readymades, it operates scenographically and explicitly incorporates viewers and their lived realities. Do you aspire to create work that goes beyond the art field’s stipulations and economic parameters, so that you can engage a broader audience?

Outside Henrike Naumann’s studio, 2020

NAUMANN: For one thing, I’m deeply involved in my work and want to keep control. For another, I also want to be able to step back so I can see it less as my property than as something held in common. Given how much social history feeds into my work, it isn’t mine alone. My work also draws on everyday culture and on art history – above all, on forgotten East German art history – and I feel like this entails a particular responsibility. Ultimately, I’m continuing something that had been thought of for a long time as finished and hugely devalued, yet I’m now working to bring it back into view. And leaving aside the fact that my work is made from knowledge and objects I claim no ownership of, the way I work is antithetical to the traditional notion of genius, where the art emerges mystically from the artist. My film professor in Babelsberg always emphasized how important it is to visualize concepts, because even if I’m not there on shoot day, things have to keep running. That’s a very different approach from fine art, where the artist-as-subject is regarded as irreplaceable.

SINOFZIK: As an artist, you still have a monopoly on your output. Even if you credit the people involved, your work is ultimately attributed to you as the creator – unlike in film, where it’s attributed to a crew. Still, the distance you describe seems essential to me. Does it, perhaps, also make it easier for you to self-represent your work on the business side?

NAUMANN: Maybe that distance is what makes my model of self-representation possible in the first place. Sometimes I feel like I’m working for the estate of an artist, who is also me. Because, as far as I see it, I also represent social interests; it’s also easier for me to fight to keep a work in a particular collection. I don’t just do that for myself. To my mind, a ton of people are involved in my installations, and every one of them has their own aspirations and contributions. If I’m working to keep a piece with ties to the art history of the GDR in a German museum – just as an example – I’m also doing it for everyone who was artistically active in East Germany. That’s why the long view matters so much to me, too: When it comes specifically to topics, subject positions, and perspectives that have never been included in conventional narratives, institutions tend to relegate them to panel discussions or to the supporting program as performances. Then they think they can just tick the box without anything having to change on a more substantial level. To my mind, it’s only what stays in the holdings that holds up. That’s why I hold institutions to their responsibilities to create space for alternative perspectives. Which is a challenge, especially for a woman artist who works on an expansive, space-filling scale and for whose work physical experience is paramount. When I say I need space, that might mean that the Beuys holdings have to be reduced. I get pushback on this sometimes, because people think the notion of demanding the same kind of space that male artists, in particular, have demanded isn’t in keeping with the spirit of the times. My response to them is that it’s the men of the Western canon who have to make space, not least for women artists and works from the East.

Inside Henrike Naumann’s studio, 2020

SINOFZIK: It takes years of relationship-building to win the trust of institutional decision-makers. I remember a conversation with Susanne Pfeffer, who placed that trust in you early, one example of that being her acquisition of 14 Words (2018), a large-scale installation made from the interior of a flower shop in Saxony, for the MMK in Frankfurt am Main.

NAUMANN: What’s key is that in certain institutions, there were – and still are – people who understood my work from the start and considered it important. I often stay in touch with them for years, and my work frequently grows out of conversations with those people at institutions. But each piece continues to evolve too, like when it’s encountered by audiences in a museum. So for me, the process isn’t over once a work has been acquired; it’s more that I want to stay in dialogue, because that’s how it gains layers of meaning. That’s why I also maintain a huge press archive, which for me isn’t just documentation – it’s something I actively work with.

SINOFZIK: Artists often leave the upkeep of their press archive to their galleries. But in your case, it sounds like getting projects off the ground and developing them – and even the other work that comes later, once the project itself is complete – are integral to your practice. For me, that raises the question of how much weight you give to art criticism.

NAUMANN: Art criticism is super stimulating for me, but it’s just one among many forms of public reception I care about. My press archive has articles from The New York Times sitting alongside pieces from the Chemnitzer Morgenpost. There’s another section that has letters from the public who write to me about the feelings they get from my exhibitions. And it’s specifically because direct contact matters so much to me – with the press as well as with the public – that I’m determined to keep my business small.

Inside Henrike Naumann’s studio, 2020

SINOFZIK: How small is your studio right now?

NAUMANN: I’ve got one employee working part-time: my studio manager. Everyone else is there on a per-project basis or freelance. So even if there’s only one person there who’s getting their social insurance payments covered, for me it’s important that everything’s set up as fairly as possible, rather than demanding that everyone’s constantly on call. I’ve often had the experience of it going another way, so I want to break that vicious circle and ensure that there’s no reproduction of precarity. Part of that is demanding certain things from the market, in my case, from the institutional side. Artists don’t just need to earn money they can live on – they need enough to create good working conditions for others. I’m responsible for the people I work with, of course – whether that’s my studio manager or the producers and art handlers who are there on a per-project basis. Having that in mind helps me in negotiations, too.

SINOFZIK: I’m struck by how aware you are of your commercial responsibilities. During a round of major structural change in the art world back in the 1990s, the stigma associated with the commercial side of things led more and more art dealers to take on the title of gallerist, which elevated the profession while downplaying its economic dimension. These days, people are less hesitant to bring the art field’s economic processes into view – for instance, by using business terms such as manager. It can also mean addressing your own commercial responsibilities as an artist. These kinds of ideas are central to a new generation of artists who are working in institutional critique and bringing transparency to fees, production costs, budgets, and so on. I’m thinking of artists like Ghislaine Leung. It’s hard to say whether calls for greater transparency will gain traction in the art field, especially given the economic uncertainties we’re experiencing … Speaking of transparency and economics, I’d also like to ask about pricing: Without the help of a gallery, how do you set your prices?

Henrike Naumann, “Ostalgie,” Busch-Reisinger Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, 2024

NAUMANN: I state my prices very clearly because they’re based on what I need as an artist and for my studio to sustain my practice. Most artists sell their work at fairs or through galleries and, in contrast to my approach, are happy to donate it to institutions so they can be in public collections. I support myself through museums and public funding. That’s why I have to hold institutions accountable and say, If you want my work, then you need to do your part in ensuring the viability of the model I’ve designed for my practice. I have to make a living, pay my staff, and make sure I can keep working like this long-term. And I think that’s the key difference that leads me – and maybe other artists of my generation, too – to make those demands. After all, we don’t use exhibition venues just to show 20 new paintings that then get carted off to some private apartment or other; we actually produce for those venues, that is, for the work to remain with the institution. So the institution isn’t just the place, the framework, the space where this demand is negotiated. It’s also the one it’s addressed to.

SINOFZIK: Beyond the physical space for your installations, you also insist on the space that is necessary for the negotiations that go with them, because your dealings with institutions don’t just involve you as an artist but also as an entrepreneur.

NAUMANN: Exactly. Institutions become places for processes that wouldn’t otherwise happen there to this extent, because they’re typically handled by galleries. I’m really clear in saying that I produce for you, so you have to engage with me on prices and production conditions. For me, you’re the places where my installations operate, but that also means you’re responsible for enabling my work and my model. Often enough, the people in the institutions have never dealt with these kinds of demands. And I don’t doubt that there are a lot of people who have a romanticized idea of it, shaped by 20th-century stories about sales straight from the studio. Or they start by assuming I just don’t have a gallery yet and still need to break into the business. There are a lot of people who don’t get it right away that I want to work independently and represent my work myself.

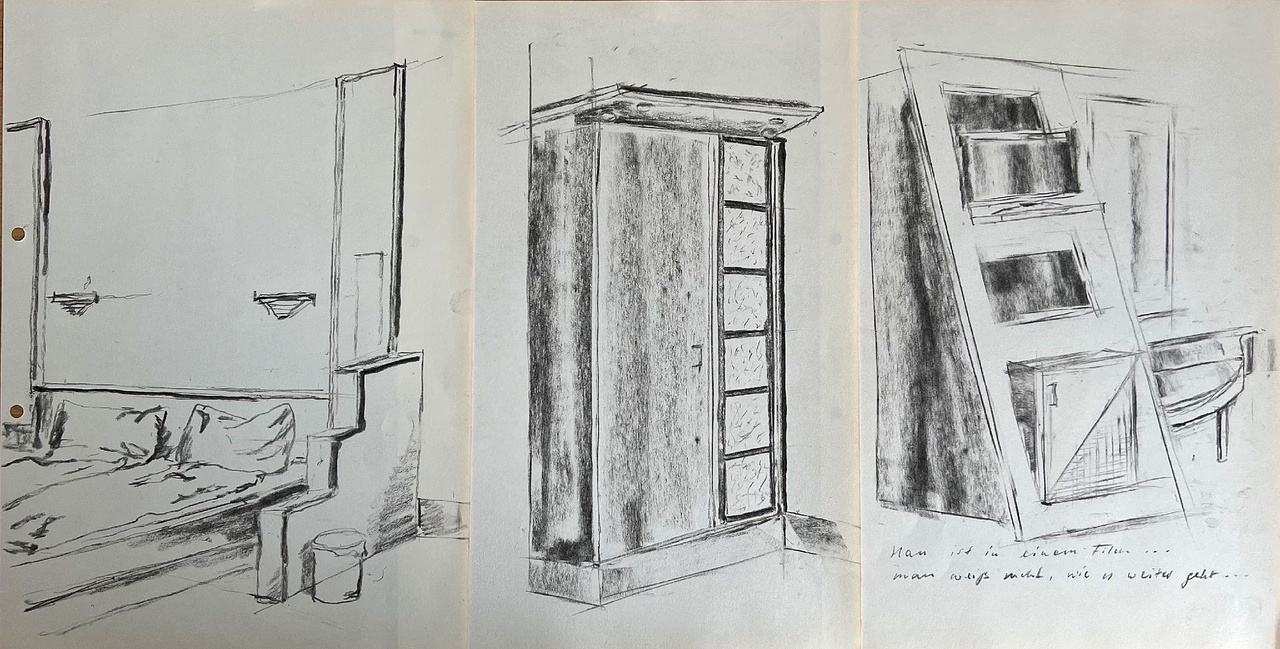

Henrike Naumann, drawings created in the context of “Bitterfelder Hof,” 2022

SINOFZIK: Right now, institutional interest in your work is strong, even while museums are facing budget cuts. They have to act economically, too. But obviously, their funding depends heavily on political contexts.

NAUMANN: That’s also why I’m so glad that I managed to sell my piece Ostalgie to the Busch-Reisinger Museum, one of the Harvard Art Museums, just before Trump took power. In that case, it took four years, but now the success is all the sweeter for me. When the political climate turns, like right now in the United States and to a lesser extent here in Germany, private spaces and structures might become more important again, including for my work.

SINOFZIK: In the context of repressive politics, let me briefly go back to your approach and how it relates to a socialist notion of art. I remember that, a while ago, we chatted about your grandfather, the artist Karl Heinz Jakob, whose work – like a portrait of miners – has since become part of your installations. He also founded a drawing group in Zwickau. I’m assuming that this drawing-group tradition was formative for you, too, in terms of your relationship to the public-facing side of art and the educational/outreach side of your work.

NAUMANN: Absolutely. What my granddad did was known as the Bitterfelder Weg (Bitterfeld Way) and was tied back to the Bitterfeld Conference, which happened in the 1950s. The idea was that art had to be comprehensible, that it had to be accessible to the workers. Back then, my granddad got sent to a coal mine, the VEB Steinkohlenwerk, to make traditional portraits of the miners. But he also set up a drawing group there for workers and ran it for the rest of his life. Later on, the circle became wider, and the membership became more diverse; kids and teenagers started coming, too. And that’s how I also got started drawing there at some point. Then for the 2022 Osten Festival, I led a drawing group myself, where we drew furniture instead of portraits. The group was held at the Hotel Bitterfelder Hof, where the conference had been held back in the day and which had had a postmodern renovation in the 1990s, so we also talked about the historical connections. Of course, I’m very critical of East Germany’s repressive cultural policy; I’ve engaged with the topic extensively. But the idea of art having a public mandate has definitely shaped me. As did the notion that art isn’t a commodity to be privately owned, that it actually belongs to everyone. Now that I’m working within the Western-shaped art system and benefiting from it too, it’s important to me to build a bridge: so, running a lucrative private-sector business with my art while at the same time trying to keep market dynamics from dictating terms any more than they have to.

Henrike Naumann with photos documenting the “Bitterfelder Weg,” 2022

SINOFZIK: On your work with institutions, which we’ve discussed, the German Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, where you’ll be presenting with Sung Tieu, poses a particular challenge. How are you taking things in the run-up?

NAUMANN: This challenge comes with some big questions, of course. For example, what does it mean to represent a country in this context? But because I deliberately seek out institutions that are historically charged, that I can engage with in terms of the politics of history and ideological critique, it really does feel like the “final boss.” I also see the whole thing less as an honor and more as an interesting problem or a complex set of questions. To my mind, the biggest challenge is staying true to myself and the principles I’ve developed, even under such intense pressure. I want to come out of this project feeling I did something good with it – and not that the project did something with me. Like with everything I make, I want to take something away from it, rather than being carried along by it.

Translation: Matthew James Scown

Henrike Naumann lives and works in Berlin. In her immersive installations, she arranges furniture and objects to create scenographic spaces that explore the friction between opposing political opinions in dealing with taste and personal everyday aesthetics. Important exhibitions of her works have been held at SculptureCenter in New York, the Busch-Reisinger Museum at Harvard University, Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, the Berlin Wall Memorial of the German Bundestag, the Ghetto Biennale in Haiti, and the Kyiv Biennale in Ukraine. With Sung Tieu, she will represent Germany at the 61st Venice Art Biennale in 2026.

Anna Sinofzik is a writer and senior editor at TEXTE ZUR KUNST.

Image credits: 1. Courtesy President and Fellows of Harvard College, photo Tara Metal; 2. Photo Axel Schneider; 3-5. Photos Henrike Naumann; 6. Courtesy President and Fellows of Harvard College; 7 + 8. Photos Henrike Naumann