As early as 2002, our observation that more and more art critics were shying away from negative assessments led us to devote an issue to scathing reviews. Since then, however, the relations of dependency within the close-knit yet heavily segmented field of art have only grown stronger. As the decreasing number of reviews and the downsizing of newspapers’ culture section editorial teams illustrate, criticism’s position has weakened across the cultural sector; on social media, some people even openly rant against critics. The influencer Rezo, for example, recently called a music critic for “Die Zeit” a “victim” because she dedicated more than five minutes to an album she thought was a flop. But as democratic structures and critical voices both find themselves on the defensive, it is more important than ever to empower critics, as Isabelle Graw argues in the following pages with reference to her analysis of a systemic transformation of the art economy.

THESIS 1: ART CRITICISM OSCILLATES BETWEEN WEAKNESS AND RESILIENCE.

In the past 35 years – since this magazine was founded – the question of how art criticism is doing has come up for discussion on a regular basis. Most commentators have diagnosed its decline; recently, so did Benjamin Buchloh, asserting in conversation with Hal Foster that the “critic” was disappearing in favor of agents with market expertise. Such farewells to criticism, it appears to me, intensify whenever the art economy as a whole is going through a “reset.” Also during the current “downward trend in the art market,” a growing chorus of voices has proclaimed with finalistic certainty that independent art criticism is now dead once and for all. Yet if there is indeed evidence that criticism has been increasingly on the defensive in recent years – especially in the commercial sphere – there is also much to suggest that, against all odds, it carries on. The fact that this magazine has been around for so many years is only one reason to think that there is still an audience for art criticism supported by theoretically ambitious arguments.

That is to say, art criticism is both weakened and resilient. Its current weakened state may even predestine it for an especially clear-eyed analysis of the process of its own marginalization and the associated economic changes in the artistic field: As a kind of “participant observer,” it is perfectly capable of subjecting its own situation in the market to self-critical examination. So instead of lapsing once more into the kind of “gestures of self-repudiation” that are constitutive of art criticism, I want to use the following pages to examine the crisis of criticism in light of a changed art economy.

THESIS 2: THERE ARE NUMEROUS SYMPTOMS OF CRISIS, BUT THERE ARE ALSO THINGS THAT CAN BE DONE ABOUT IT.

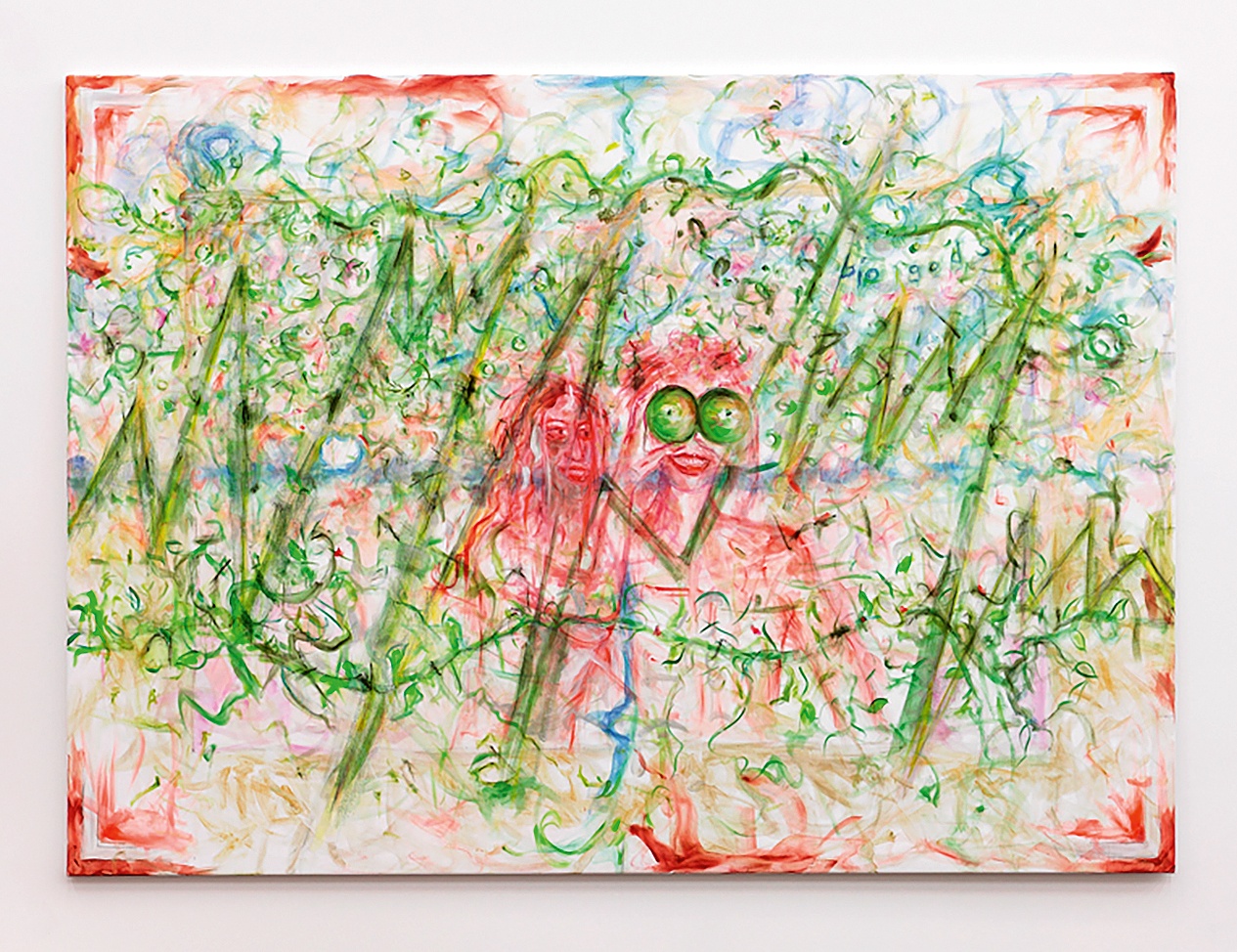

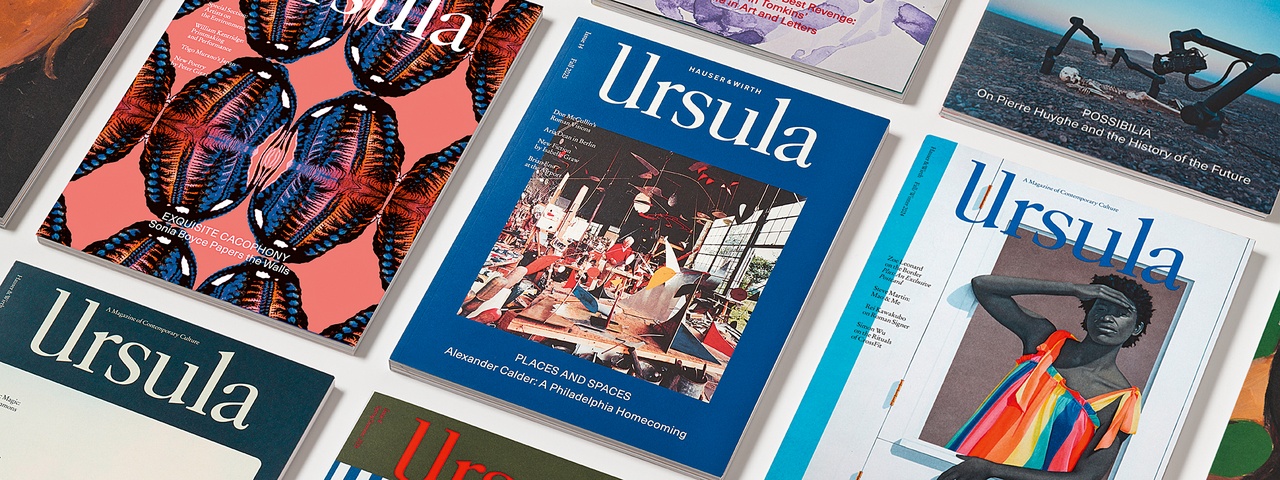

For an illustration of art criticism’s current weakened condition, consider the recent news that The New York Times laid off four of its longest-serving art and culture critics. A comparable development can also be observed in German newspapers’ culture pages – here, too, the staff positions of departing critics are often left unfilled, signaling the decline in criticism’s importance. It fits that periodicals more and more often run interviews with VIPs rather than reviews, the defining format of critical evaluation, as though artists were best suited to explaining their own “products.” The room for critical engagement with works of art is shrinking even in art magazines, which now often publish PR copy in exchange for ad placements, effectively turning criticism into affirmative press releases. To make matters worse, criticism’s autonomy is under threat: When art magazines such as Artforum are bought up by large media corporations, they lose their institutional independence. Numerous critics (myself included) now also write for the customer magazines released by major galleries like Hauser & Wirth (Ursula) or Gagosian (Gagosian Quarterly), which will not run any critical objections to the artists they represent – but at least they pay their writers well. As those galleries often present museum-quality exhibitions – in New York, Gagosian opened a fantastic Pablo Picasso show this spring, and Hauser & Wirth mounted a magnificent Francis Picabia presentation – writing for them increasingly appeals to art historians as well; the galleries’ lavishly designed catalogues provide an opportunity for in-depth scholarly discussion of the works on view. Needless to say, though, those catalogues are not venues for independent criticism either. At the recent Art Basel Paris, the marginalization of art criticism was even enacted spatially: Walking along the trade fair’s outer perimeter, I encountered the tiny exhibition stands of a select few art magazines. Almost no one else strayed that far from the real action.

If by criticism we mean the articulation of situated, nuanced, and reasoned aesthetic value judgments, then it is on the retreat in the online sphere as well. Parts of the art world’s distribution system have been hijacked by the tech industry, so that many of its social interactions now take place on Instagram, where everyone knows it is quantity rather than quality that reigns supreme: The number of followers or likes determines the putative relevance of a creative practice. Another novel challenge is that auction results are promptly published on platforms like Artnet online – a work’s market value is no longer a secret and comes to serve as a benchmark on which many collectors base their expectations. Very few buyers of art would nowadays consult an art historian’s writing before bidding for a work. The main gauge of artistic relevance is a work’s price.

In terms of its form, too, criticism is under pressure on the internet. Constant scrolling leaves readers with shortened attention spans, making them less likely to read extended art-historical essays or exhibition reviews. In their stead, online dissemination promotes formats such as podcasts or short reels by influencers.

A superficial glance at the online sphere might mislead us into thinking that criticism, far from weakened, is actually omnipresent – social media, after all, are flooded with critical takes. But a personal opinion is not the same as criticism, the more so since the latter ideally strives to support itself with reasoned arguments. If criticism finds itself on the defensive, so does the democratic order on which it rests, as recent developments in the United States illustrate. The dismantlement of democratic structures and the silencing of criticism go hand in hand. Critics of the Trump administration must now fear reprisals. Needless to say, criticizing an artist’s oeuvre is less dangerous than criticizing an autocratic president. But art criticism, too, presupposes democratic conditions. In that sense, any defense of criticism implies a defense of democracy.

THESIS 3: THE PURSUIT OF CONTROVERSY HAS YIELDED TO THE DESIRE FOR AGREEMENT.

To gain a better understanding of art criticism’s current condition, we should look back on the 1990s. As I recall, both artists and gallery owners at the time were extraordinarily interested in critical engagement. The former positively courted controversial discussion of their practice – controversy, they thought, was what gave it meaning. Since then, however, the situation has changed completely. Most actors in the artistic field yearn for assurance and agreement, something that is noticeable, for example, at symposia. Where audiences used to pick speakers’ talks apart, general assent is now the rule. Then again, this desire for harmony is understandable given the multiple crises rattling today’s world. People would rather not lay themselves open to another attack, another challenge. Similarly, critics are hardly keen on the trouble that a negative review might get them into. They prefer to write about practices they hold in esteem. The downside of this development is that a work of art is no longer seen as the “nexus of a problem,” which would imply that it is essentially contestable. What one often encounters instead is art-critical and art-historical writing that decorates its object with affirmative ornaments of significance. Rare is the critic who actually expresses a personal position on the object under consideration. Yet when critics do not take stances, they weaken criticism from the inside, effectively exacerbating its structural weakness with a kind of self-inflicted impairment.

THESIS 4: ART CRITICS HAVE DISCOVERED A NEW FIELD OF OPERATION FOR THEMSELVES – THE MARKET REPORT.

Since the fall of last year, news of negative developments in the art market has been coming thick and fast. Websites like Artnet and Artnews bring fresh disaster reports almost daily. Sales at galleries and auction houses declined by up to 30 percent in the first half of 2025; works by yesteryear’s market stars, including Alberto Giacometti, have remained unsold at auctions; and the formerly brisk trade in the output of artists like Andy Warhol and Gerhard Richter is dwindling. The extreme downward trend has also affected the London branch of Hauser & Wirth, where profits are said to have plummeted by 90 percent. This summer, numerous middle-segment galleries, including Blum Gallery and Venus Over Manhattan, shut down. Pace will soon close its showroom in Hong Kong, and Almine Rech is shuttering its London branch. The reports spreading news of these developments often strike an apocalyptic note, as though the art market’s collapse is imminent. Yet as a closer look reveals, sales in the upper market segment are still high – though significantly lower than they were – so more than a little of this is complaining from a position of relative comfort.

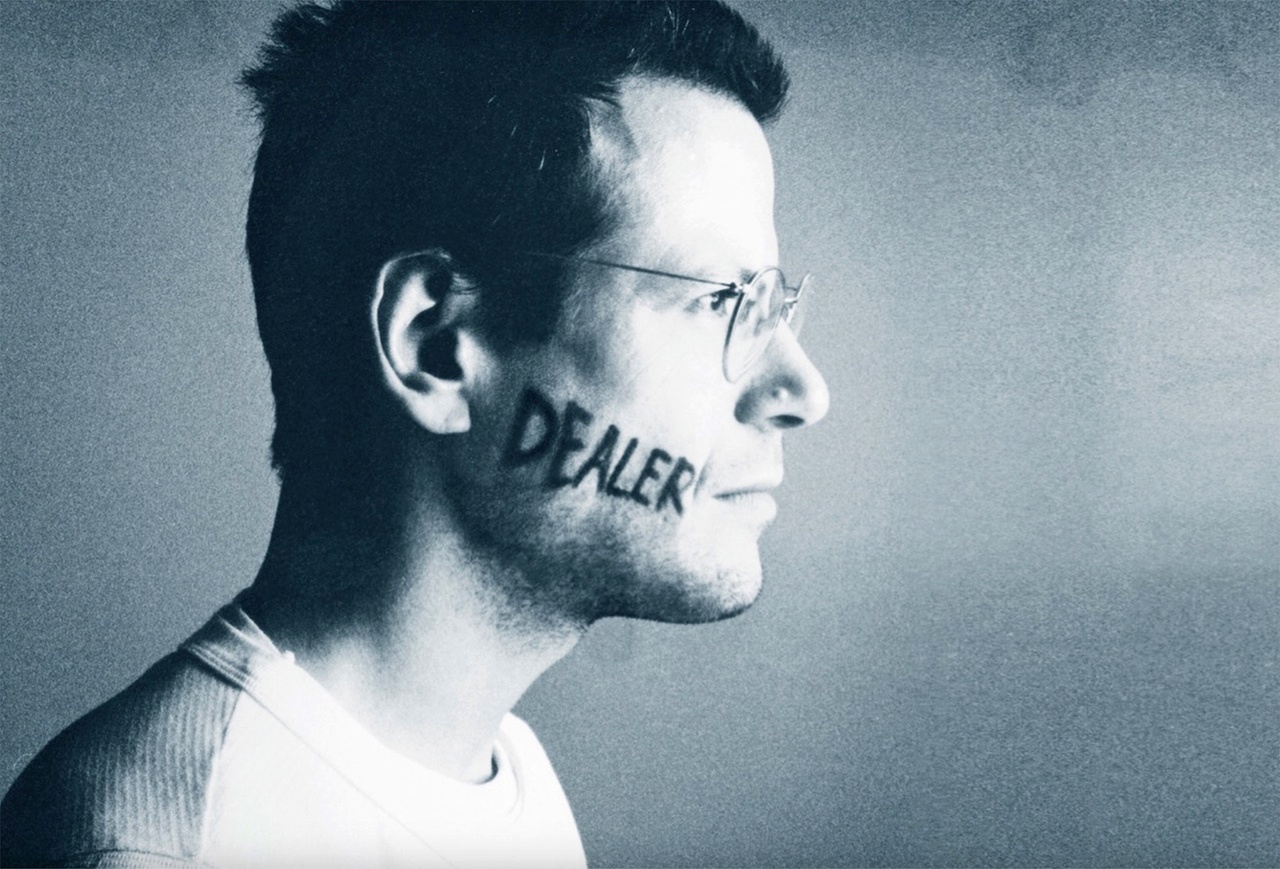

With a view to the unending series of bad news, Kenny Schachter – himself the author of a number of art-market obituaries – recently told his colleagues to quit the “Olympian levels of competitive complaining.” One would have to agree with him that negative market reports reinforce the downward trend – this crisis is one of confidence first and foremost, as Marc Glimcher, CEO at Pace, recently emphasized in an interview: “People start to lose confidence.” Uncertainty in the market environment corrodes trust. There is reason to think that it is, above all, the “spec collectors” (Schachter’s term) looking for a quick profit who are shying away from buying in light of the news of falling auction prices. Meanwhile, it looks like the old-fashioned, well-informed connoisseur collector who reads up on the art, takes a long view, and swims against the current is dying out, which means there are very few collectors left who see times of falling prices as an opportunity to buy works of high symbolic value at a bargain.

Back to Schachter and his rebuke to his colleagues. It is understandable that he would be weary of alarming news, but I believe he is overlooking a crucial point: the intrinsic connection between criticism and crisis. The two, after all, are interdependent, as Reinhart Koselleck already noted: Critique needs crisis because the latter justifies its existence, and the crisis, conversely, urgently calls for critique. But where Koselleck, not unlike Schachter now, argued that critique merely wrote the crisis into existence, I think that critique’s mission, especially in times of crisis, is to be keenly sensitive to the looming changes in its economy and to subject them to analysis. So instead of merely documenting this most recent structural shift of the art economy in market reports, art criticism should historicize it and offer a sociologically informed interpretation. This text is an attempt at such interpretation.

THESIS 5: THE ART ECONOMY IS AN “ECONOMY OF QUALITIES” THAT ITS ACTORS INCESSANTLY REFLECT ON AND DISCUSS.

If many actors in the art market are preoccupied with its crisis right now, I believe that is because of the special characteristics of this economy. That is why I propose that we see the art economy, following Michel Callon, Cécile Méadel, and Vololona Rabeharisoa, as an “economy of qualities” – an economy whose primary objective is the qualification and positioning of its products. That is to say that the art economy is about giving those products – works of art or projects – a profile, singularizing them. Another feature of the “economy of qualities” that Callon, Méadel, and Rabeharisoa highlight is its reflectiveness. The participants in this economy are constantly communicating about its condition and organizational form. If so many people pipe up about the current art-market crisis, then that is also an expression of this economy’s reflective nature. Take the abovementioned Marc Glimcher, who has offered a dramatic image to illustrate the condition of the art market today: “The art market is a train wreck everywhere and that’s ok. It’s long overdue.” On the one hand, Glimcher’s metaphor implies that the current art-market crisis is nothing short of a disaster that will necessitate extensive cleanup operations. On the other hand, he thinks this disastrous development is perfectly fine because it was to be expected for quite some time, along the lines of: Any boom will be followed by a bust. The gallerist Tim Blum, who decided to close up shop this summer after 30 years, describes his gallery’s demise as the consequence of a dysfunctional “system” that is not working anymore. In other words, it was not his own actions as an entrepreneur but the “system” that was responsible for his business’s failure. In emphasizing this structural dimension, Blum is not even wrong; the current crisis is also a crisis of the gallery business model. To remain competitive, he explains, galleries must participate in more and more fairs and bring in enough revenue to cover the high rental fees for booths, an imperative of expansion that is impossible to keep up with in the long run. Besides the crisis symptom he mentions, we may note that middle-segment gallerists, in particular, must constantly be alert to the danger of having their economically successful artists be poached by bigger players like Gagosian or Hauser & Wirth. And given their high operating expenses, they can no longer operate as the “risk takers” they used to be. On the contrary, they are highly risk averse; exhibitions of works by young artists that don’t sell immediately are something they simply cannot afford. Some galleries now even demand that artists cover their own storage and production expenses, which would have been unthinkable in the 1990s. Many young artists respond by relying on alternative distribution channels like Instagram, which, however, come with new dependencies of their own.

Finally, Blum draws attention to an intellectual deficit that reveals something important about the condition of criticism: He says that at the last Art Basel, he did not have even one “meaningful conversation.” While he does not mention that small talk can be very “meaningful,” his observation that substantial discussions about artworks no longer take place in the mercantile sphere touches on a key point. The fact that ever fewer people at fairs talk about art or know what is at stake in a work of art at a given point in time is another consequence of the marginalization of art criticism in that sphere.

THESIS 6: ART CRITICISM HAS BEEN STEADILY LOSING INFLUENCE SINCE THE 1960S.

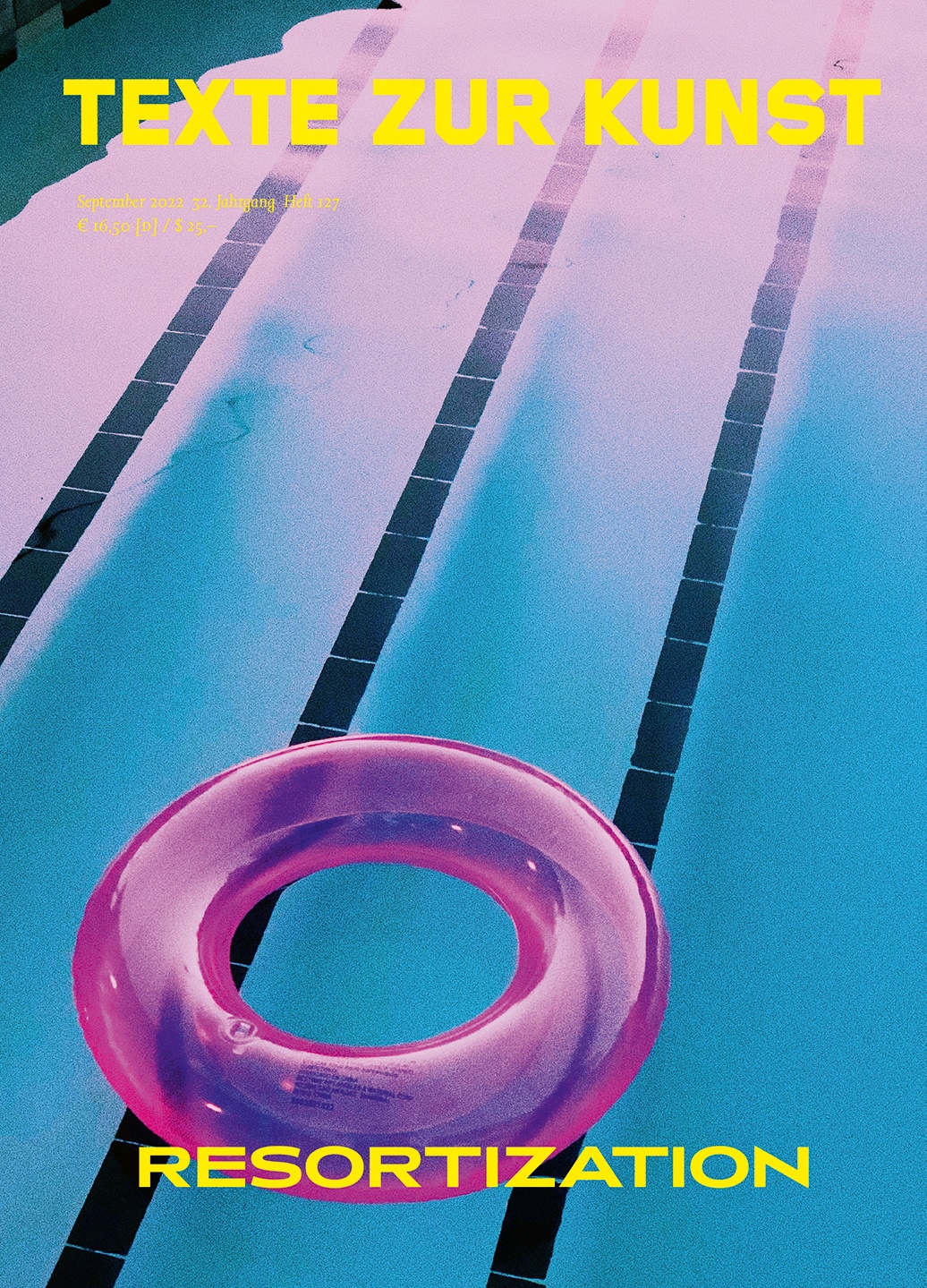

As noted above, all actors in an “economy of qualities” are occupied with qualifying and positioning the products. Art criticism plays a special role in this process of attributing meaning: Merely by singling out certain works as exceptional, it advances their singularization and hence, crucially, also their value formation. That is its mission. Within the framework of what Cynthia and Harrison White have called the dealer-critic system, which emerged in the late 19th century and supplanted the Salon system, it was indeed critics’ responsibility to profile works of art in this way and, together with the dealers, to position them. However, by the 1990s if not earlier, this dealer-critic system was replaced by what I have elsewhere called the dealer-collector-curator system. Now it was the curators and collectors who took the lead in the process of value formation. With the inexorable rise of economic considerations in the artistic field, critics lost influence. Another structural change in the art economy that implied a weakening of art criticism was what I discussed in 2022 under the title “Resortization.” Among other phenomena, I described the tendency of mega-galleries to open branches in the luxury enclaves of the rich: in places like Aspen, Monaco, or Menorca, where gallery owners and their wealthy collectors remain largely among themselves. With a bit of exaggeration, we might say that these art resorts are intellectual-free zones because, given the high travel and accommodation costs, critics visit them only as part of paid press junkets, if at all. What is more, I believe the resortization process is reshaping the online art world as well – on Instagram, for example, where the retreat into resort-like bubbles in which people encounter only like-minded others results in constant mutual confirmation. Here, too, criticism is a lost cause.

THESIS 7: AS THE FASHION WORLD ALREADY DEMONSTRATES, ANY ATTACHMENT EVENTUALLY GIVES WAY TO DETACHMENT.

Raymonde Moulin already noted in the 1990s that the contemporary art market is particularly sensitive to economic fluctuations. The uncertainties of today’s world with its wars, economic crises, climate disasters, and unpredictable right-wing populist politicians similarly have a direct impact on the art market. In this sort of environment, it is hard to imagine the “positive futures” that are so vital to the process of value formation. In analogy with other markets, the art market, too, goes through cycles: Every boom is followed by a crash, every recession by another rally. It is even able to recover quite quickly, as was on display at the recent Art Basel Paris. Numerous gallerists had to rehang their presentations day after day because they had sold out their booths. However, this upswing appeared to be due to a “Paris effect” rather than a general stabilization of the market. Be that as it may, the actors in an “economy of qualities” need to keep in mind that every attachment eventually flips to detachment (and vice versa). Consumers who have become emotionally attached to certain products will at some point turn their backs on them: “All attachment is constantly threatened.” Given this fundamentally precarious product loyalty, we might say that competition among gallery owners is primarily about delaying the detachment of their own collectors for as long as possible. However, their efforts on this score are foiled by the increased power of auction houses. Works seeing massive price drops at auctions, or even remaining unsold, can not only spell the end of an artist’s career but may also prompt collectors to avoid the works of artists with low market values. When it comes to pricing, galleries also find themselves driven into a corner by auction houses. They are compelled to adjust their prices to the lower auction results, which used to be taboo because it upset clients who had previously paid more for works. My observation is that many collectors now avoid the primary market, going bargain hunting at provincial auctions instead.

Something similar is playing out in the world of fashion: The luxury industry, like the upper segment of the art market, is struggling with sharply declining sales. And fashion devotees are no longer shopping in expensive boutiques but are instead buying designer wear at bargain prices on platforms like Vinted. According to Forbes, even wealthy customers in the luxury industry are no longer willing to accept price increases when quality is declining. They prefer to spend their money on adventure travel, wellness retreats, or longevity treatments – a trend that is also beginning to make itself felt in the art world. Moreover, similar to the decline in the importance of art criticism in the commercial segment of the art world, fashion criticism has been sidelined as well. There may still be a few fashion bloggers or Instagram or Substack posts that review runway shows, but in the major fashion magazines, criticism no longer exists. The editor of one such magazine recently told me off the record that he was not allowed to publish a single critical word about Louis Vuitton’s latest collection; doing so would be punished with the cancellation of all advertisements placed by the LVMH conglomerate, which would be tantamount to committing professional suicide. Meanwhile, authors of scathing reviews in the art world also must be prepared to be sanctioned – they may no longer be invited to the dinner or entrusted with writing for catalogues. At the same time, though, I often hear people – gallerists and curators, in particular – say that they miss the “critical writing making substantive arguments” genre. So there is still hope.

THESIS 8: THE ART WORLD HAS A MILIEU PROBLEM, AND HERE, TOO, CRITICISM CAN BRING RELIEF.

When I began writing art criticism a full 40 years ago, I was fascinated not only by certain artistic practices but also by the art milieu. My impression back then was that this was where the most interesting and advanced debates were happening. I wanted to be part of a world in which something seemed to be genuinely at stake. The situation is quite different nowadays. While there are still segments of the art world where theoretically ambitious discussions take place, especially in the blue-chip sector the money aspect has become primary. In the 1990s, the symbolic capital of critics and theorists was still in great demand. Today, by contrast, we can often see players in the art world throw themselves at the feet of millionaire collectors or artists who are exceptionally successful in the market. In many instances, financial pressures necessitate such obsequiousness. But the result is that money is credited with absolute authority, as if high market value were unimpeachable. Auction results, too, now wield the kind of interpretive power that imperious critics like Clement Greenberg once held; they can boost an artist’s career or bring it to an abrupt end. On the other hand, as the economic imperative reigns supreme in the art world, it has become less appealing to cultural producers from other industries. With my friends and acquaintances from the film and music industries, for example, I have observed that they are hardly keen on going to art openings, highly hierarchical affairs where they are constantly given to understand that, as putative non-buyers, they do not matter. At gallery dinners, the moneyed elites are often seated at the main table and kept apart from everyone else. People with cultural capital, on the other hand, are treated like the unpopular kids in high school.

What this situation calls for, it seems to me, is a kind of reset in which cultural capital is rehabilitated, its significance restored, and criticism, including criticism of the works of commercially successful artists, is welcomed and encouraged. Furthermore, art fairs should not grant the super-rich privileged access, as Art Basel Paris did just now with an “avant-première,” an extra preview for billionaires. Instead, measures might be taken to promote social fluctuation: Art fairs should be open to all interested parties from day one, just like the Salons of the 18th century, which were also frequented by people from all classes – one reason for their extraordinary popularity. Major galleries might follow the lead of their smaller competitors and forgo fixed seating arrangements during gallery dinners, allowing people from different financial backgrounds to mingle. There is no question that it takes a certain kind of expertise to understand the language of art, and so entry into contemporary art will always be contingent on certain social and intellectual prerequisites. But instead of ostracizing this knowledge from the market sphere, it should be invited back in. Introducing collectors to critics and vice versa used to be common practice; now it is the rare exception. It might enable collectors to learn more about the specific symbolic intervention a work of art represents (and about the particular context into which it intervenes) and help them be less fixated on prices going forward. Conversely, art critics might gain more insight into the functioning of an economy of which they themselves are part – many of them maintain the illusion that they stand outside of it, when of course critics are, in reality, also actors in the market, not least because they contribute to the process of value formation.

Finally, the current structural transformation of the art economy raises the question: Are we facing a restructuring of the art system similar to the one that took place in the late 19th century, when the dealer-critic system replaced the Salon system, or is this merely a minor correction and shift? It remains to be seen which actors would call the shots in a new system and which power differentials would structure it. Coming from a critic, this may sound both self-interested and like wishful thinking, but I am confident that art criticism will play a defining role in this structural transformation. Its mission will not merely be to analyze its own crisis or serve as an agent. It will raise well-founded objections to what is celebrated in the market and champion specific oeuvres, whether commercially successful or not. And because it will develop new online formats as well, it will be paid more attention, and its influence will be valued. There is even reason for optimism, considering that criticism is still happening in the private realm, where friends continue to discuss exhibitions in a controversial manner. Art criticism has been declared dead many times, and for this very reason, it has a long life ahead of it.

Editorial note: Some ideas and earlier versions of passages in this essay are also found in “Letter from the Publisher,” which was mailed out as part of our newsletter on November 1, 2025. That letter included a preliminary form of some of the reflections collected in the following pages.

Translation: Gerrit Jackson

Isabelle Graw is the cofounder and publisher of TEXTE ZUR KUNST and teaches art history and theory at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste – Städelschule in Frankfurt am Main. Her most recent publications include In Another World: Notes, 2014–2017 (Sternberg Press, 2020), Three Cases of Value Reflection: Ponge, Whitten, Banksy (Sternberg Press, 2021), On the Benefits of Friendship (Sternberg Press, 2023), and Fear and Money: A Novel (Sternberg Press; MIT Press, 2025).

Image credits: 1. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Buchholz; 2. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth; 3. Courtesy Kenny Schachter; 4. Courtesy Pace Gallery, photo Suzie Howell; 5. © Estate of Martin Kippenberger, Galerie Gisela Capitain; 6. © TEXTE ZUR KUNST; 7. courtesy @jerrygogosian

Notes